War/Photography: An Interview with Simon Norfolk

[Image: Simon Norfolk. "King Amanullah’s Victory Arch built to celebrate the 1919 winning of Independence from the British. Paghman, Kabul Province." From Afghanistan: Chronotopia.]

[Image: Simon Norfolk. "King Amanullah’s Victory Arch built to celebrate the 1919 winning of Independence from the British. Paghman, Kabul Province." From Afghanistan: Chronotopia.]As photographer Simon Norfolk claims in the following interview, his work documents an international "military sublime." His photos reveal half-collapsed buildings, destroyed cinemas, and unpopulated urban ruins in diagonal shafts of morning sunlight – from Iraq to Rwanda, Bosnia to Afghanistan – before venturing further afield into more distant, and surprising, landscapes of modern warfare. These include the sterile, climate-controlled rooms of military command centers, and the gargantuan supercomputers that design and simulate nuclear warheads.

As Norfolk himself writes, in a short but profoundly interesting text called Et in Arcadia Ego: "These photographs form chapters in a larger project attempting to understand how war, and the need to fight war, has formed our world: how so many of the spaces we occupy; the technologies we use; and the ways we understand ourselves, are created by military conflict."

Indeed, he reminds us, "anybody interested in the effects of war quickly becomes an expert in ruins."

[Image: Simon Norfolk. "Rashid Street in Central Baghdad. The buildng on the right overlooks the bridge and so was heavily damaged in the fighting."]

[Image: Simon Norfolk. "Rashid Street in Central Baghdad. The buildng on the right overlooks the bridge and so was heavily damaged in the fighting."]Norfolk's written work delivers crisp and often stunning insights about urban design and historical landscapes. Later, in the same essay, he writes:

- What these "landscapes" have in common – their fundamental basis in war – is always downplayed in our society. I was astounded to discover that the long, straight, bustling, commercial road that runs through my neighbourhood of London follows an old Roman road. In places the Roman stones are still buried beneath the modern tarmac. Crucially, it needs to be understood that the road system built by the Romans was their highest military technology, their equivalent of the stealth bomber or the Apache helicopter – a technology that allowed a huge empire to be maintained by a relatively small army, that could move quickly and safely along these paved, all-weather roads. It is extraordinary that London, a city that ought to be shaped by Tudor kings, the British Empire, Victorian engineers and modern international Finance, is a city fundamentally drawn, even to this day, by abandoned Roman military hardware.

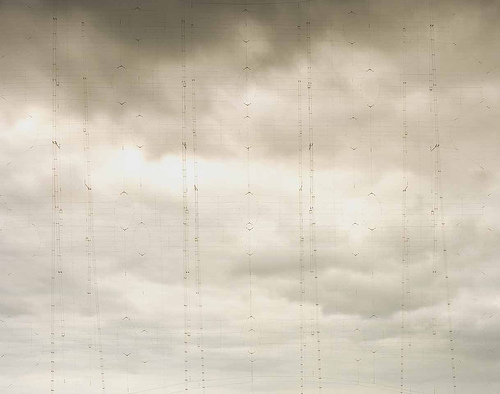

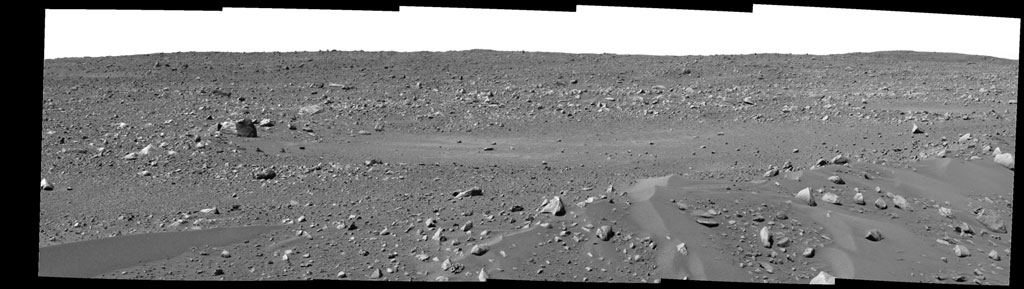

As Norfolk explains: "Although only 64 km square and mostly ash and lava fields, the island is festooned with more than 100 antenna relays. These are bizarre; like some kind of aerial spaghetti. Some are wire versions of the Millennium Dome; some like large skeletal bomber aircraft raised on tall pylons; and some are delicate cones and spirals." This technologically Dr. Seuss-like landscape, "against a background of lifeless, red, volcanic ash is unearthly – more akin to a base on Mars."

[Image: Simon Norfolk. Ascension Island, South Atlantic. "On the edge of the Broken Tooth Live Firing Range on the slopes of Sister's Peak. Tyre tracks by the RAF. Distant aerials part of the American-controlled complex along Pyramid Point Road. In the far distance Cross Hill with another American facility on its peak."]

[Image: Simon Norfolk. Ascension Island, South Atlantic. "On the edge of the Broken Tooth Live Firing Range on the slopes of Sister's Peak. Tyre tracks by the RAF. Distant aerials part of the American-controlled complex along Pyramid Point Road. In the far distance Cross Hill with another American facility on its peak."]Norfolk and I soon set up an interview, which appears below. We discuss European Romanticism and the paintings of Claude Lorrain; the long-term urban effect of WWII bombing raids over Germany; Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness; the military origins of grain in black and white film; genocide; the invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan; modern art; the modeling of nuclear warheads; and how to survive snipers in a combat zone – including some unexpected fashion tips for other war photographers.

Norfolk is the author of For most of it I have no words (with Michael Ignatieff), Bleed, and Afghanistan: Chronotopia.

We spoke via telephone.

[Image: Simon Norfolk. "Bullet-scarred outdoor cinema at the Palace of Culture in the Karte Char district of Kabul." From Afghanistan: Chronotopia.]

[Image: Simon Norfolk. "Bullet-scarred outdoor cinema at the Palace of Culture in the Karte Char district of Kabul." From Afghanistan: Chronotopia.]BLDGBLOG: Could you start with a brief thematic introduction to your work?

Simon Norfolk: All of the work that I’ve been doing over the last five years is about warfare and the way war makes the world we live in. War shapes and designs our society. The landscapes that I look at are created by warfare and conflict. This is particularly true in Europe. I went to the city of Cologne, for instance, and the city of Cologne was built by Charlemagne – but Cologne has the shape that it does today because of the abilities and non-abilities of a Lancaster Bomber. It comes from what a Lancaster can do and what a Lancaster can't do. What it cannot do is fly deep into Germany in the middle of the day and pinpoint-bomb a ball bearing factory. What it can do is fly to places that are quite near to England, that are five miles across, on a bend in the river, under moonlight, and then hit them with large amounts of H.E.. And if you do that, you end up with a city that looks like Cologne – the way the city's shaped.

So I started off in Afghanistan photographing literal battlefields – but I'm trying to stretch that idea of what a battlefield is. Because all the interesting money now – the new money, the exciting stuff – is about entirely new realms of warfare: inside cyberspace, inside parts of the electromagnetic spectrum: eavesdropping, intelligence, satellite warfare, imaging. This is where all the exciting stuff is going to happen in twenty years' time. So I wanted to stretch that idea of what a battleground could be. What is a landscape – a surface, an environment, a space – created by warfare?

[Image: Simon Norfolk. "Victory arch built by the Northern Alliance at the entrance to a local commander’s HQ in Bamiyan. The empty niche housed the smaller of the two Buddhas, destroyed by the Taliban in 2001." From Afghanistan: Chronotopia.]

[Image: Simon Norfolk. "Victory arch built by the Northern Alliance at the entrance to a local commander’s HQ in Bamiyan. The empty niche housed the smaller of the two Buddhas, destroyed by the Taliban in 2001." From Afghanistan: Chronotopia.]BLDGBLOG: And that's how you started taking pictures of supercomputers?

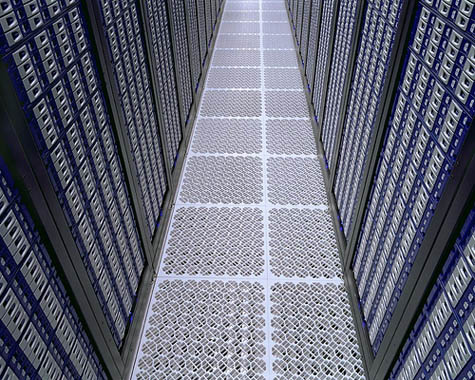

Norfolk: Those supercomputers – big BlueGene, in particular – those are battlegrounds. BlueGene is designing and thinking about a space that is only about 30cm across and exists for about a billionth of a second, and that’s an exploding nuclear warhead. BlueGene is thinking about and modeling that space very intensely, because what happens there is very complicated.

That computer is as much a battlefield as a place in Afghanistan is, full of bullet holes.

[Image: Simon Norfolk. "BlueGene/L, the world's biggest computer, at Lawrence Livermore Laboratory, California, USA. It is the size of 132,000 PCs. It is used to design and maintain America's nuclear weapons." On his website, Norfolk notes that the computer is used for "modeling physics inside an exploding nuclear warhead."]

[Image: Simon Norfolk. "BlueGene/L, the world's biggest computer, at Lawrence Livermore Laboratory, California, USA. It is the size of 132,000 PCs. It is used to design and maintain America's nuclear weapons." On his website, Norfolk notes that the computer is used for "modeling physics inside an exploding nuclear warhead."]BLDGBLOG: In the context of those computers, your references to the divine proved quite controversial – in the comments, for instance, at the end of that earlier post on BLDGBLOG where the photographs appeared. Could you talk more about these overlaps between the military, computer technology, and what you think is "godlike" about the latter?

Norfolk: Where weapons and supercomputers fit in for me is in a military-industrial complex. The problem is that that complex has drifted off so far above any idea of democratic control – even Eisenhower pointed this out – that I would call it godlike. It's beyond irrational, it’s beyond any kind of comprehension in a scientific sense. It's designing nuclear weapons that can destroy the world more efficiently – when we already have nuclear weapons that can destroy the world many times over.

People seem to think that I’m saying oh, they’re full of gods, or look, this is where god lives... But obviously I don’t think that. I don’t think that those computers are somehow unprogrammed by humans, or supernatural. What I’m concerned about is that those humans, who have programmed them, aren’t warm and fuzzy professors like The Nutty Professor. They're introverted people working in the basements of DynaCorp, and General Dynamics, and Raytheon, and they’re so far beyond any kind of democratic control that you or I will ever have over what they do.

It ends up being like a relationship with the sublime – a military sublime. All of the work I'm doing, I might even call it: "Toward a Military Sublime." Because these objects are beyond: they’re inscrutable, uncontrollable, beyond democracy.

[Images: Simon Norfolk. Top: The Mare Nostrum, housed in a deconsecrated church in the Barcelona Supercomputer Centre, Spain. Middle: "Commissariat à l'énergie atomique, Bruyers-le-Chalet, near Paris. CEA designs and maintains France's nuclear weapons. Installation of the new Tera10 supercomputer. The red poles are to prevent any accidents by falling down the open holes during installation." Bottom: CEA. "A 'cold aisle' between two rows of TERA-1 racks."]

[Images: Simon Norfolk. Top: The Mare Nostrum, housed in a deconsecrated church in the Barcelona Supercomputer Centre, Spain. Middle: "Commissariat à l'énergie atomique, Bruyers-le-Chalet, near Paris. CEA designs and maintains France's nuclear weapons. Installation of the new Tera10 supercomputer. The red poles are to prevent any accidents by falling down the open holes during installation." Bottom: CEA. "A 'cold aisle' between two rows of TERA-1 racks."]BLDGBLOG: One of your photographs from Ascension Island shows a perfectly white-washed church – but, in the background, you see a military radar installation. There’s a fantastic overlap there between the theological lines of communication represented by the church, and the military/electromagnetic lines of communication represented by the radar. Both are immaterial, but both appear in the photograph.

Norfolk: [laughs] I've just been in the Outer Hebrides, off the coast of Scotland, where they have one of the biggest missile testing ranges in the world. It's mainly a radar site – to follow the missiles down-range, when they fire missiles into the north Atlantic – but there's other stuff out there, too: there's submarine surveillance stuff and ocean surveillance stuff, and it's all on top of this mountain range. But at the foot of the mountain there's also a statue of the Madonna. It’s called The Madonna of the Isles – but the local people call it Where God Meets Radar.

[laughter]

It's a bugger, though, because the way the mountain curves, you can't actually get a picture of both of them at the same time. There's no place you can actually get both things in the same frame. But when you visit, it's just extraordinary: she's a statue about 25' high, with a child in her arms, made out of white marble, and on the hill about 100' above are these huge white radomes, with these silently circling radar dishes.

[Image: Simon Norfolk. Ascension Island, South Atlantic. "The Church Of St Mary in Georgetown with Cross Hill in the background with an American radar facility on its summit."]

[Image: Simon Norfolk. Ascension Island, South Atlantic. "The Church Of St Mary in Georgetown with Cross Hill in the background with an American radar facility on its summit."]BLDGBLOG: Your photos are usually unpopulated. Is that a conscious artistic choice, or do you just happen to be photographing these places when there's no one around?

Norfolk: Well, part of this interest of mine in the sublime means that a lot of the artistic ideas that I'm drawing on partly come out of the photography of ruins. When I was in Afghanistan photographing these places – photographing these ruins – I started looking at some of the very earliest photojournalists, and they were ruin photographers: Matthew Brady's pictures of battlefields at Gettysburg, or Roger Fenton's pictures from the Crimea. And there are no dead bodies. Well, there are dead bodies, but that’s very controversial – the corpses were arranged, etc.

But a lot of those photographers were, in turn, drawing upon ideas from 17th century and 18th century French landscape painting – European landscape painting. Claude Lorraine. Nicolas Poussin. Ruins have a very particular meaning in those pictures. They're about the folly of human existence; they're about the foolishness of empire. Those ruins of Claude Lorraine: it's a collapsed Roman temple, and what he's saying is that the greatest empires that were ever built – the empire of Rome, the Catholic church – these things have fallen down to earth. They all fall into ivy eventually.

So all the empires they could see being built in their own lifetimes – the British empire, the French empire, the Dutch empire – they were saying: look, all of this is crap. None of this is really permanent: all of these things rise and fall. All empires rise and fall and, in the long run, all of this is bullshit.

I wanted to try to copy some motifs from those paintings – in particular, that amazing golden light that someone like Claude Lorraine always used. Even when he does a painting called Midday, it's bathed in this beautiful, golden light. To do that as a photographer, I can't invent it like a painter can; I have to take the photographs very early in the morning. So they're all shot at 4am.

[Image: Simon Norfolk. Ascension Island, South Atlantic. "The BBC World Service Atlantic Relay Station at English Bay."]

[Image: Simon Norfolk. Ascension Island, South Atlantic. "The BBC World Service Atlantic Relay Station at English Bay."]BLDGBLOG: So of course no one's around!

Norfolk: It is partly because of that that people aren't there – but it's also... for me, I think people kind of gobble up the photograph. They become what the photograph is. For me, people just aren't that important; it's about this panoptic process, it's about this kind of eavesdropping, it's about this ability to look into every aspect of our lives. And I think if you put people into these pictures, I don't know – it would draw viewers away. It would draw viewers into the story of the people. It's not about, you know, Bob who runs the radar dome; it's about this thing that looks inside your email program, and listens to this phone call, and listens to every phone call in the world in every language, and washes it through computer programs. And if you say plutonium nerve gas bomb to me over the telephone, in an instant this computer is looking at what web pages you've been to recently, it's looking at my credit card bills, it's looking at your health records, it's looking at the books I check out of the library. That's what frightens me – it's not about: here's Dave, he works on the computer systems for Raytheon...

So I've always tried to pull people out of the pictures – and, if they're in my pictures, it's usually because they represent an idea, really. I think if you're going to talk about Dave, or Bob, or Wendy, you have to do it properly. You either do it properly or you don't do it at all.

[Image: Simon Norfolk. Ascension Island, South Atlantic."The BBC World Service Atlantic Relay Station at English Bay."]

[Image: Simon Norfolk. Ascension Island, South Atlantic."The BBC World Service Atlantic Relay Station at English Bay."]BLDGBLOG: How did you get to Ascension Island in the first place? Can anyone just buy a ticket ticket and go there?

Norfolk: You have to fill in a permission form – but, yeah, you can buy a ticket. A lot of birdwatchers go down to the Falklands, and airplanes have to refuel at Ascension Island. It's expensive, but you can do it.

You also have to fill in a form which they go through, and it says what you're up to and all the rest of it. So I'd filled in the form, and I'd said I was a photographer – but I got there and no one had read the forms! On my last day on the island, I phoned up and said: I'm a photojournalist, and I've been on the island for two weeks, and can I talk to someone up there...? And they fucking crapped themselves. They said how did you get here? Didn't you fill out the forms? And I said yeah, didn't you read the forms?

And they said, well – actually, nobody reads the forms.

[laughter]

BLDGBLOG: So much for international surveillance.

Norfolk: They also didn't pick up any emails that said I was going to Ascension Island.

BLDGBLOG: Or any phonecalls you made while staying there.

Norfolk: It's run by clowns, of course.

[Image: Simon Norfolk. Ascension Island, South Atlantic. "Looking towards the cinder cone of Sister's Peak from English Bay Road. On the edge of the Broken Tooth Live Firing Range."]

[Image: Simon Norfolk. Ascension Island, South Atlantic. "Looking towards the cinder cone of Sister's Peak from English Bay Road. On the edge of the Broken Tooth Live Firing Range."]BLDGBLOG: It often seems like the most interesting thing about these places is what cannot be photographed.

Norfolk: Absolutely – absolutely. That's why, whenever you see warfare now, it's photographed in that same dreary, clichéd way: it's metal boxes rolling across the desert. Every time you switch on CNN, or buy a newspaper, you see guys in metal boxes – because that looks good. These photojournalists, and these TV crews, they don’t explain the process: they show things that look good on TV. A satellite orbiting in space doesn't look good. A submarine – you know, the greatest platform we've ever built for launching nuclear weapons and for surveillance – that has no presence whatsoever in how most people understand what the military does today.

The same is true of electromagnetic stuff – information warfare, cyber-warfare – and I wonder what photojournalists of the future are going to photograph? Are they still going to photograph guys with guns, shooting at each other? Because quite soon there aren't going to be guys with guns shooting at each other. We're quite soon getting to the era of UAVs and stuff. People aren't even going to know what shot them – and there will be nothing to photograph.

[Images: Simon Norfolk. "The supercomputer at the Wellcome Trust's Sangar Institute, Cambridge, UK."]

[Images: Simon Norfolk. "The supercomputer at the Wellcome Trust's Sangar Institute, Cambridge, UK."]BLDGBLOG: Except for empty rooms and computer systems.

Norfolk: Exactly. Look at the way the war in Afghanistan was photographed: what you got was a guy on a ridge in a turban watching a very, very far away explosion. That was war photography! That was the way the Afghan war was covered. What worries me is that, if these wars become invisible, then they will cease to exist in the popular imagination. I'm very worried that, because these things become invisible, they just – people don’t seem to be fucking bothered.

But, you know, wouldn't it be amazing to have a series of portraits printed of missile systems, but you photographed them the way you'd photograph a BMW?

[laughter]

You get them straight off the production line in the factory, and then you polish them, and you wax them – so they’re just beautiful – and then you light them the way you would an Audi TT, with a black background, and you shoot them on a big camera. Just gorgeous – sculptural. Then the caption says, you know: Predator Drone. Hellfire Missile. Nuclear Warhead.

BLDGBLOG: It's interesting that, on your website, it says you gave up photojournalism to move into landscape photography – yet that seems to have coincided with a more explicit politicization of your work.

Norfolk: Yeah, absolutely.

BLDGBLOG: So your projects are even more political now – yet they’re intended as landscape photography?

Norfolk: I mean, I didn't get fed up with the subjects of photojournalism – I got fed up with the clichés of photojournalism, with its inability to talk about anything complicated. Photojournalism is a great tool for telling very simple stories: Here's a good guy. Here's a bad guy. It's awful. But the stuff I was dealing with was getting more and more complicated – it felt like I was trying to play Rachmaninoff in boxing gloves. Incidentally, it's also a tool that was invented in the 1940s – black and white film, the Leica, the 35mm lens, with a 1940s narrative. So, if I'm trying to do photojournalism, I'm meant to use a tool that was invented by Robert Capa?

I needed to find a more complicated way to draw people in. I'm not down on photojournalism – it does what it does very well – but its job is to offer all its information instantly and immediately. I thought the fact that this place in Afghanistan – this ruin – actually looks a little like Stonehenge: that interested me. I wanted to highlight that. I want you to be drawn to that. I want you to stay in my sphere of influence for slightly longer, so that you can think about these things. And taking pictures in 35mm doesn't do it.

So the content of photojournalism interests me enormously, it's just the tools that I had to work with I thought were terrible. I had to find a different syntax to negotiate those things.

BLDGBLOG: Ironically, though, your photos haven't really been accepted by the art world yet – because of your subject matter.

Norfolk: Well, I cannot fucking believe that I go into an art gallery and people want to piss their lives away not talking about what’s going on in the world. Have they not switched on their TV and seen what's going on out there? They have nothing to say about that? They'd rather look at pictures of their girlfriend's bottom, or at their top ten favorite arseholes? Switch on the telly and see what's going on in our world – particularly these last five years. If you've got nothing to say about that, then I wonder what the fucking hell you're doing.

The idea of producing work which is only of interest to a couple of thousand people who have got art history degrees... The point of the world is to change it, and you can't change it if you're just talking about Roland Barthes or structuralist-semiotic gobbledygook that only a few thousand people can understand, let alone argue about.

That's not why I take these photographs.

[Images: Simon Norfolk. Top: "Wrecked Ariana Afghan Airlines jets at Kabul Airport pushed into a mined area at the edge of the apron," from Afghanistan: Chronotopia. Bottom: "The illegal Jewish settlement of Gilo, a suburb of Jerusalem. To deter snipers from the adjacent Palestinian village of Beit Jala (seen in the distance) a wall has been erected. To brighten the view on the Israeli side, it has been painted with the view as it would be if there were no Palestinians and no Beit Jala."]

[Images: Simon Norfolk. Top: "Wrecked Ariana Afghan Airlines jets at Kabul Airport pushed into a mined area at the edge of the apron," from Afghanistan: Chronotopia. Bottom: "The illegal Jewish settlement of Gilo, a suburb of Jerusalem. To deter snipers from the adjacent Palestinian village of Beit Jala (seen in the distance) a wall has been erected. To brighten the view on the Israeli side, it has been painted with the view as it would be if there were no Palestinians and no Beit Jala."]BLDGBLOG: Clearly you're not taking these pictures – of military supercomputers and remote island surveillance systems – as a way to celebrate the future of warfare?

Norfolk: No, no. No.

BLDGBLOG: But what, then, is your relationship to what you describe, in one of your texts, as the Romantic, 18th-century nationalistic use of images, where ruined castles and army forts and so on were actually meant as a kind of homage to imperial valor? Are you taking pictures of military sites as a kind of ironic comment on nationalistic celebrations of global power?

Norfolk: No, I don't think it's ironic. I think what I'm in favor of is clarity. What annoys me about those artists is that there were things they actually stood for, but what seems to have happened is their ideas have been laundered. They've been infantilized. I don't mind what the guy stands for – I just want to know what the guy stands for. I don’t want some low-fat version of his politics. And unless you can really understand what the fellow stood for, how can you comprehend what his ideas were about? How can you judge whether his paintings were good paintings or rubbish paintings?

The thing that pisses me off about so much modern art is that it carries no politics – it has nothing that it wants to say about the world. Without that passion, that political drive, to a piece of work – and I mean politics here very broadly – how can you ever really evaluate it? At the end of the day, I don't think my politics are very popular right now, but what I would like to hear is what are your politics? Because if you're not going to tell me, how can we ever possibly have an argument about whether you're a clever person, your work is great, your work is crap, your art is profound, your art is trivial...?

For instance, I'm doing a lot of work these days on Paul Strand – and Paul Strand is a much more interesting photographer than most people think he is. The keepers of the flame, the big organizations that hold the platinum-plating prints and his photogravures, or whatever – these big museums, particularly in America, that have large collections – they don't want the world to know that Strand was a major Marxist, his entire life. He was a massive Stalinist. That just dirties the waters in terms of knowing who Strand was. So Strand has become this rather meaningless pictorialist now. You look at any description of Strand's work, and he was just a guy who photographed fence posts and little wooden huts in rural parts of the world. If you don't understand his politics, how can you make any sense of what he was trying to do, or what he photographed? These people have completely laundered his reputation – completely deracinated the man.

[Image: Simon Norfolk. Staircase at Auschwitz, with worn footsteps.]

[Image: Simon Norfolk. Staircase at Auschwitz, with worn footsteps.]BLDGBLOG: How does working outside of photojournalism, and even outside the art world, affect the actual practicality of getting into these places – photographing war zones and ruins and so on? You weren’t an embedded photographer in Iraq?

Norfolk: No, no. I was just kind of winging it.

You know, the camera I use is made of wood – it's a 4x5 field camera, made of mahogany and brass – and it looks like an antique. Part of what I do is I make sure I don't look very serious – it's best to look like a harmless dickhead, really, so no one bothers you. You look like a nutter. And, to be honest, I play that up: I've got the bald head, and the Hawaiian shirt, and, to look at the image on the back of the camera, you have to put a blanket over your head and go in there with a magnifying glass, and it’s always on a tripod.

So I have two choices: I can either do these images from a speeding car, or I can stand there with a blanket over my head, and look like such a prick that somebody's going to find me through their rifle scope and think: Oh! What's that? Let's go down and have a look... I can’t believe that photographers go into war zones dressed like soldiers! Soldiers are the people they shoot at. If I could wear a clown suit I would do it – if I could wear the big shoes and everything. I would wear the whole fucking thing.

I think there's a lot to be said for that, actually, because I can either scrape in there on my belly, wearing camo, and sneak around; or I can stand right there in front, wearing a shirt that says, you know, Don't shoot me. I’m a dick.

[Image: Simon Norfolk. "Storage depot for the oil-fired power station at Jiyé/Jiyeh bombed in the first few days of the [Israel-Hezbollah] war and still on fire and still dumping oil into the sea 20 days later. Seen from the Sands Rock Resort, 1 Aug 2006."]

[Image: Simon Norfolk. "Storage depot for the oil-fired power station at Jiyé/Jiyeh bombed in the first few days of the [Israel-Hezbollah] war and still on fire and still dumping oil into the sea 20 days later. Seen from the Sands Rock Resort, 1 Aug 2006."]BLDGBLOG: Of course, you read how more journalists, photographers, and television reporters have been killed, or taken hostage, in Iraq over the last two years alone than were killed during the entirety of the Vietnam War – but, of course, this is the war where they’ve been embedded. They’re all –

Norfolk: The way the embeddeds are dressed!

BLDGBLOG: They’re dressed like combatants.

Norfolk: What are you thinking, going around in brown trousers and stuff? I don't want to say that the people are to blame for what happened to them – but I would not do that. I just would not do that. You know those orange vests that guys working on the roads wear? I've had those made with the word Artist on the back. [laughs]

BLDGBLOG: You’ll probably get shot by a soldier now.

Norfolk: [laughs] So the practicalities – I mean, you still have to be able to shift like a journalist does. You have to find out where things are, what's going on – and you still have to get there.

[Image: Simon Norfolk. "A controlled explosion of an American fuel convoy in Iraq being filmed on the set of Over There, a Fox TV production about the life of a US Army platoon in contemporary Iraq. Being filmed in Chatsworth, just north of Los Angeles, Sept 2005."]

[Image: Simon Norfolk. "A controlled explosion of an American fuel convoy in Iraq being filmed on the set of Over There, a Fox TV production about the life of a US Army platoon in contemporary Iraq. Being filmed in Chatsworth, just north of Los Angeles, Sept 2005."]BLDGBLOG: In your photos of movie sets, where a war scene is being filmed, it's very clear that we're looking at a staged event. It doesn't look anything like real warfare. But have you ever found that the situation is reversed – where you're shooting a real war scene, in Baghdad, say, but all the reporters from CNN and the BBC make it look like some kind of TV set?

Norfolk: Oh, yeah, yeah – on the roof of the Palestine Hotel. You're up on the big, flat roof of the hotel, and you're looking down on this ballroom, and the streets of Baghdad are below that. The reporters were all camped out on the roof of this ballroom – with little tents and little pergolas with lights and generators and stuff – and you could see where it was evening in the world because you could see whose TV crews were up and working. You could see all the Europeans were out – oh, it must be 6 o'clock in Europe. Oh, it must be 7 o'clock now in the U.S., because all the Americans are out. Then the Japanese come out later on, and they do it all at 3 o'clock in the morning because that's 5 o'clock in Japan, or whatever. They're all sharing gear and generators and stuff, and using the same background – but they're acting like they're on their own, out on the frontline. Standing right next to each other. Quite bizarre. It was like some kind of casting for a new film.

There are these weird layers. When I photographed the Iraq movie, it was done, interestingly, in the same place where they made the M*A*S*H TV series – which is why it looks like M*A*S*H The same landscape that could be M*A*S*H could also be North Korea – and it could also be Iraq. What else could it be? Greenland? [laughs] So there are these weird layers of history – and weird layers of non-history, as well. These juxtapositions of time kind of crashing into each other.

The first book I did, the Afghanistan book, I called it Chronotopia, and that's a term taken from Mikhail Bakhtin. The idea of the chronotope – chronos is time, and topos is place – is any place where these layers of time fit upon each other. Either satisfactorily or uncomfortably – it fascinates me. Especially coming from Europe. In northern France, there are places where the English fought the French in 1347 – and it's the same place we fought the Germans in 1914, and it's the same place where the Americans rolled through in 1944. Their battle cemeteries are within a hundred yards of each other. These places have thicknesses, military thicknesses –

BLDGBLOG: It's like the Roman roads in London, that you describe in your writings: they're actually a military transport system, still there beneath modern streets. London is a military landscape.

Norfolk: Absolutely: it's military technology left lying around. This stuff comes down to us. You know, the reason I can take night shot photographs is not because Mr. Kodak wanted me to take these photographs, but because he needed to design a certain kind of film that could go into a Mosquito bomber and take reconnaissance photographs during the Second World War. That's really when all the advances in film were made – in grain-structure – and it was for aerial reconnaissance.

[Image: Simon Norfolk. From "Hotel Africa."]

[Image: Simon Norfolk. From "Hotel Africa."]BLDGBLOG: Your "Hotel Africa" series reminds me a bit of some J.G. Ballard stories – overgrown air conditioning systems, tent cities, native warfare, and so on – and you mention Shelley and Byron in some of your texts; so I'm curious if there are any intentional literary references in your work? Or is there a particular book or a particular writer who has influenced you?

Norfolk: Unfortunately, this is the biggest cliché of Africa, but the first book I wrote was pretty much based on Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness. Not because it features pictures of Africa, but because it has a curve, I think. What fascinates me about Conrad's book is that it starts in the real world, this world that we understand – they're in a boat in the Thames estuary – and he says, This, too, was one of the dark places of the earth... And what he's talking about are these chronotopes, these layered histories. Then he says, I’ll tell you a story about the Congo, and so he goes to Belgium, and then he goes to Africa, and then he starts going up the river.

So little by little you move away from these certainties; you move toward instabilities around the narrator as he talks. As he moves up the river, everything becomes harder to grasp. So the idea of that curve – I took that from Conrad.

When I did the first book, it started out with these photojournalistic pictures of genocide in Rwanda – it was about six months after the genocide, and there were 2000 bodies in one church alone. Then I went back in history, looking at other genocides that had taken place: at Auschwitz, where there's bits of evidence lying around, and then back to Namibia in 1905, and then to the Armenian genocide, where there's almost no evidence at all. There, the pictures become pictures of snow and sand, as a metaphor about a covering and a hiding, a new layer, so these evidences become harder and harder to discern and unwrap.

That was also something that I took from Conrad.

[Image: Simon Norfolk. "Tailings pond of the Petkovici Dam. A mass grave was discovered dug into the earth of the dam and bodies were also thrown into the lake." From Bleed.]

[Image: Simon Norfolk. "Tailings pond of the Petkovici Dam. A mass grave was discovered dug into the earth of the dam and bodies were also thrown into the lake." From Bleed.]Simon Norfolk will speak at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art on Saturday, December 2nd, at 4pm, in the Brown Auditorium. If you're anywhere near Los Angeles, consider stopping by.

Meanwhile, there are many, many more photographs available on Norfolk's website, and his own writings deserve a long look. His books – For most of it I have no words, Bleed, and Afghanistan: Chronotopia – are also worthy acquisitions. Shit, it's Christmas – buy all three.

Finally, a huge thank you to Simon Norfolk for his humor and patience during the long process of assembling this interview.

[Image:

[Image:  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: London, flooding; via the

[Image: London, flooding; via the  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

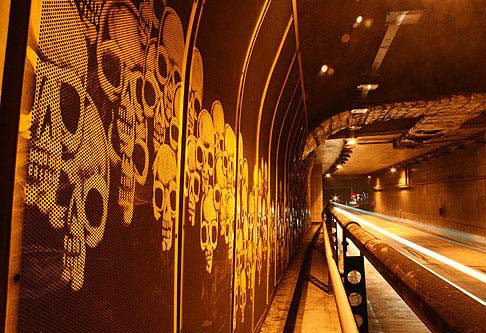

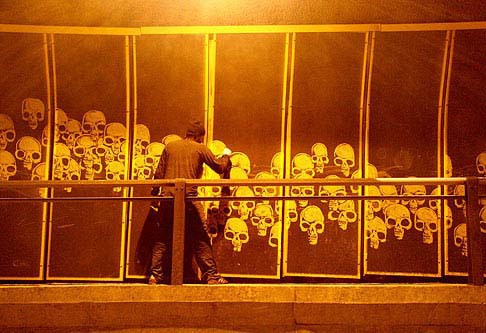

[Image:  Brazilian artist

Brazilian artist

Specifically, Orion scraped, cleaned, and rubbed down through soot "

Specifically, Orion scraped, cleaned, and rubbed down through soot " In any case, the descriptive text on Orion's website seems to go downhill fairly quickly – we're soon scraping soot off the walls of repression and peeling away consciousness itself, and we're meant to be very, very angry while doing so – but the funny thing is, because voluntarily scrubbing sections of a public underpass isn't actually illegal in São Paulo – and would seem, in fact, to be a sign of refined citizenship – try as they might,

In any case, the descriptive text on Orion's website seems to go downhill fairly quickly – we're soon scraping soot off the walls of repression and peeling away consciousness itself, and we're meant to be very, very angry while doing so – but the funny thing is, because voluntarily scrubbing sections of a public underpass isn't actually illegal in São Paulo – and would seem, in fact, to be a sign of refined citizenship – try as they might,  Instead, the fire crews showed up and washed it down with hoses.

Instead, the fire crews showed up and washed it down with hoses. One of the things I've always found most interesting about

One of the things I've always found most interesting about

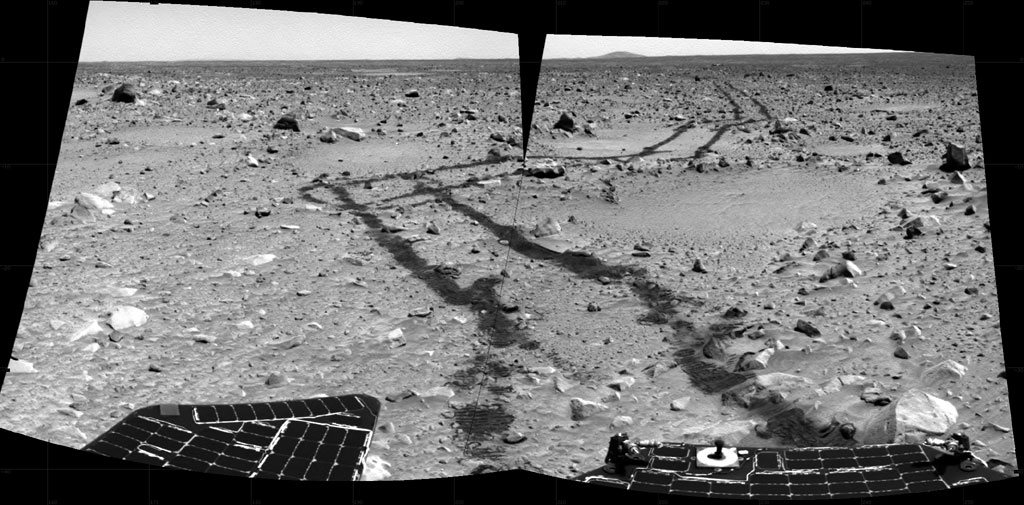

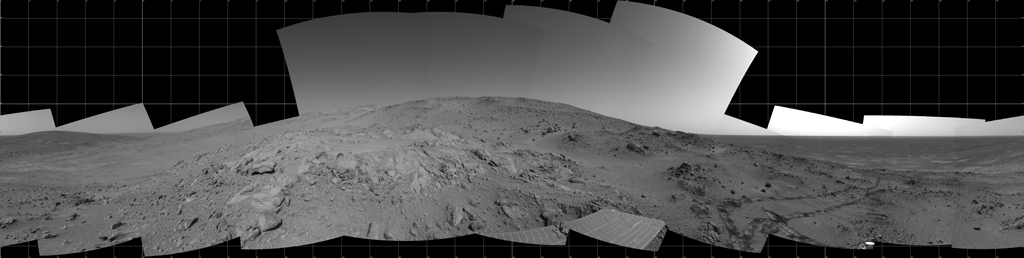

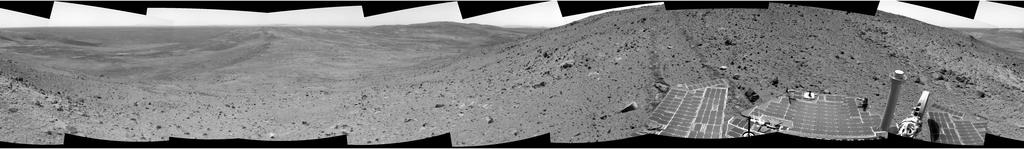

So I was pleasantly surprised to see the same approach used to the same effect, whether intentional or not, in these photos of Mt. Snowdon, Wales, taken by Flickr user

So I was pleasantly surprised to see the same approach used to the same effect, whether intentional or not, in these photos of Mt. Snowdon, Wales, taken by Flickr user  In other words, because of the culturally recent Martian resonance of spliced photography, these scenes from the earth appear unearthly; the topography – for me, at least – seems strangely removed from terrestrial expectations.

In other words, because of the culturally recent Martian resonance of spliced photography, these scenes from the earth appear unearthly; the topography – for me, at least – seems strangely removed from terrestrial expectations.  Or not, of course, in which case you just think these look like photos of Mt. Snowdon; but take several hundred more of these things, write some text – and soon you've got a new planetary narrative: discovering other worlds, right here on earth beside us.

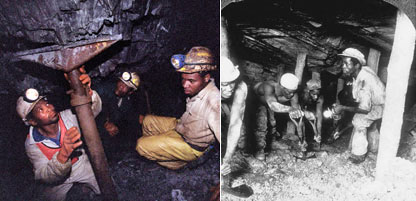

Or not, of course, in which case you just think these look like photos of Mt. Snowdon; but take several hundred more of these things, write some text – and soon you've got a new planetary narrative: discovering other worlds, right here on earth beside us. [Image: The Tau Tona mine; courtesy of

[Image: The Tau Tona mine; courtesy of  [Image: (left) Workers in a South African gold mine; via

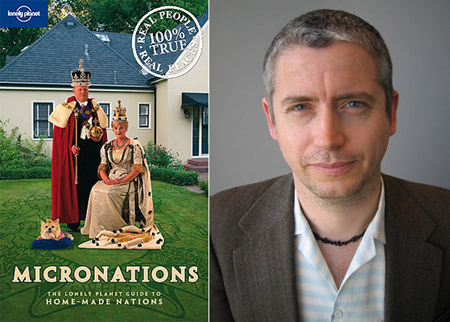

[Image: (left) Workers in a South African gold mine; via  [Images: The book and one of its authors,

[Images: The book and one of its authors,  [Image:

[Image:  [Images: The

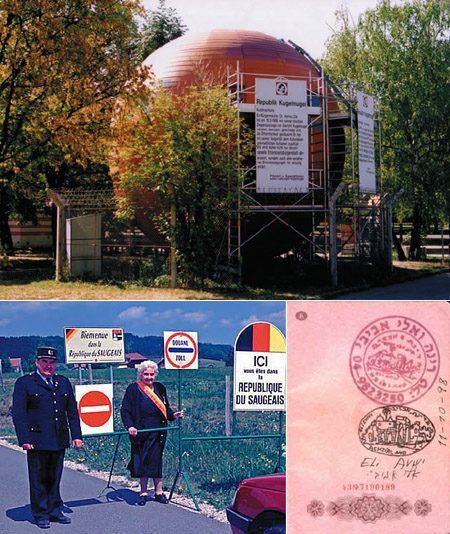

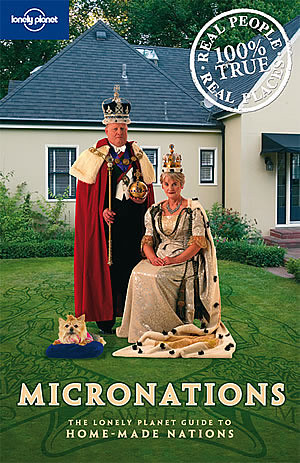

[Images: The  [Images: Kevin Baugh, President of the

[Images: Kevin Baugh, President of the  [Images: Emperor Georgius II of the

[Images: Emperor Georgius II of the  BLDGBLOG readers, now is your chance to shine: using 100 words or less, tell us what kind of micronation you would found – and where. Would it be an agricultural utopia, ruled by lottery, prone to war? Or a tropical island paradise, funded by bonds in coconut futures? Perhaps a polysexual fantasy on a hovercraft, roaring nonstop across the oceans of the world? Or a quiet Arctic refuge? A little mountain town somewhere, full of friends and wine?

BLDGBLOG readers, now is your chance to shine: using 100 words or less, tell us what kind of micronation you would found – and where. Would it be an agricultural utopia, ruled by lottery, prone to war? Or a tropical island paradise, funded by bonds in coconut futures? Perhaps a polysexual fantasy on a hovercraft, roaring nonstop across the oceans of the world? Or a quiet Arctic refuge? A little mountain town somewhere, full of friends and wine?

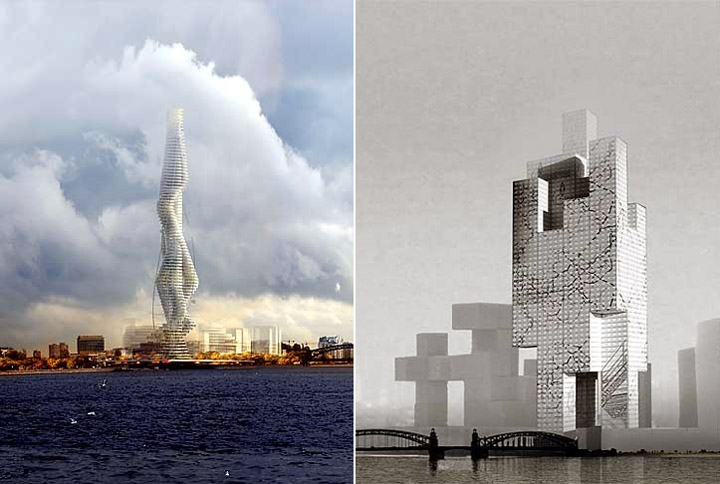

This new "city," however, will just be a cluster of high-tech administrative buildings, although the main tower "is to rise at least 300 meters (985 feet) into the sky and symbolize the growing power of the firm. It is also to be situated just opposite the famed 18th century

This new "city," however, will just be a cluster of high-tech administrative buildings, although the main tower "is to rise at least 300 meters (985 feet) into the sky and symbolize the growing power of the firm. It is also to be situated just opposite the famed 18th century

Because Gazprom City "is part of a longer range plan by Russian President Vladimir Putin to boost the prestige of his home city," however, it seems unlikely that the project will be held back. This, after all, may be St. Petersburg's newest architectural moment: "Much of the development that has occurred in recent years has benefited Moscow, whereas St. Petersburg has seen little change. Only recently, with the celebration of the city's 300th birthday in 2003, did the city begin awakening from its centuries-long sleep. But even as high-tech projects and a new theater

Because Gazprom City "is part of a longer range plan by Russian President Vladimir Putin to boost the prestige of his home city," however, it seems unlikely that the project will be held back. This, after all, may be St. Petersburg's newest architectural moment: "Much of the development that has occurred in recent years has benefited Moscow, whereas St. Petersburg has seen little change. Only recently, with the celebration of the city's 300th birthday in 2003, did the city begin awakening from its centuries-long sleep. But even as high-tech projects and a new theater  In any case, the winner of the competition will be announced on December 1st, and the actual tower should be fully constructed by 2016.

In any case, the winner of the competition will be announced on December 1st, and the actual tower should be fully constructed by 2016.