|

|

There was a fascinating article in the New York Times yesterday about a mine disaster just waiting to happen.  [Image: "Abandoned equipment stands in the snow near the top of an underground tunnel that was once used to drain mine water." Photo by Kevin Moloney for The New York Times]. [Image: "Abandoned equipment stands in the snow near the top of an underground tunnel that was once used to drain mine water." Photo by Kevin Moloney for The New York Times].In Leadville, Colorado, we read, people now wake up every morning wondering if they "will be washed away by toxic water that local officials fear could burst from a decaying mine tunnel" on the edge of town. For years, the federal Bureau of Reclamation and the Environmental Protection Agency have bickered over what to do about the aging tunnel, which stretches 2.1 miles and has become dammed by debris. The debris is holding back more than a billion gallons of water, much of it tainted with toxic levels of cadmium, zinc and manganese. The article continues, describing the background for this "potentially catastrophic release of water": Abandoned mine shafts honeycomb the surrounding hillsides. The old drainage tunnel, built by the federal government in 1943 to drain hundreds of these shafts, began falling apart in the 1970s, causing water to pool. In 2005, the E.P.A. offered to start pumping the clogged water toward a Bureau of Reclamation plant, which treats the water flowing through the tunnel; but the bureau contended that the additional water was part of the E.P.A.’s Superfund cleanup responsibility. And so nothing was done. The threat of "release" is now so great that property in the town can no longer be insured. One wonders if it might be possible to build something like this deliberately, as a military tactic: a kind of long-delay, underground water cannon that only fires once, several decades after construction. You leave a few dozen of these things lying around, beneath a terrain you have to evacuate... and so whenever your enemies move in, they've got some rather big problems beneath their feet.

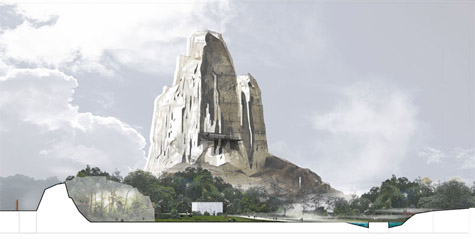

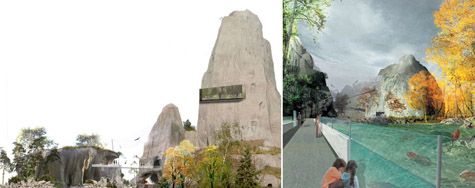

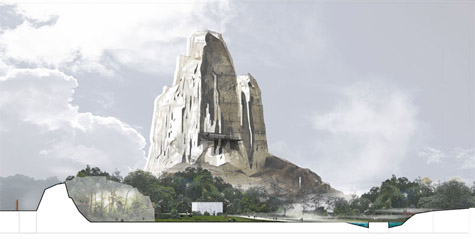

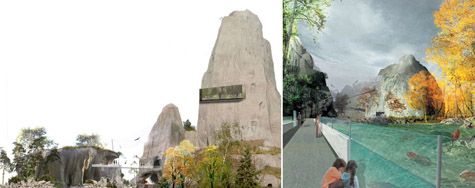

[Image: The Zoo de Vincennes, by Beckmann N'Thepe]. [Image: The Zoo de Vincennes, by Beckmann N'Thepe].These are some plans for a new zoological park in Vincennes, France. The zoo's landscapes are designed by TN PLUS Landscape Architects, its buildings by Paris architects Beckmann N'Thepe. The project is noteworthy for, among other things, what could be called its simulated geology.  [Image: Landscapes in the Zoo de Vincennes, designed by TN PLUS Landscape Architects]. [Image: Landscapes in the Zoo de Vincennes, designed by TN PLUS Landscape Architects].These artificial earthforms will contain simulated environments within which animals will live. The whole complex will encompass 15 hectares and six "biozones," and it will run partly on solar power.  [Image: The Zoo de Vincennes, by Beckmann N'Thepe]. [Image: The Zoo de Vincennes, by Beckmann N'Thepe].The park's "biozones" include the savannah, the equatorial African rain forest, Patagonia, French Guiana, Madagascar, and Europe.  [Image: More landscapes in the Zoo de Vincennes, by TN PLUS Landscape Architects]. [Image: More landscapes in the Zoo de Vincennes, by TN PLUS Landscape Architects].So the zoo – like all zoos, of course – will be a simulation intended for animals. Zoos, in other words, are a particularly bizarre form of trans-species communication, attempted on the level of architecture and landscape design. They're like hieroglyphs that animals inhabit – spaces defined entirely by their ability to refer to something they are not.  [Images: Zooscapes by TN PLUS Landscape Architects]. [Images: Zooscapes by TN PLUS Landscape Architects].More information, if you read French, is available in this PDF.  [Image: The Zoo de Vincennes, by Beckmann N'Thepe]. [Image: The Zoo de Vincennes, by Beckmann N'Thepe].And I have to say that the renderings of this place look pretty cool. But why do we only build zoos like this? Why not suburbs or college campuses? You mold landforms out of reinforced concrete, and you install artificial waterfalls and fake rivers, and you grow rare orchids under the cover of geodesic domes. And then your grandkids can grow up in a savannah-themed suburb outside Orlando. The next town over, kids run around through giant fern trees, chasing parrots. Perhaps themed biozones are the future of suburban design?  [Image: The Zoo de Vincennes, by Beckmann N'Thepe]. [Image: The Zoo de Vincennes, by Beckmann N'Thepe].Google opens a new administrative complex outside London – on the grounds of a former zoo. Your "cubicle" is partly outside. Hidden nozzles mist your neck on every lunch break.  [Image: The Zoo de Vincennes, by Beckmann N'Thepe].(Zoo de Vincennes discovered by Architectural Record). [Image: The Zoo de Vincennes, by Beckmann N'Thepe].(Zoo de Vincennes discovered by Architectural Record).

A recent landscape design competition sought to rethink the Vatnsmýri airport grounds in Reykjavík, Iceland, putting those old runways to use, for instance, as new urban park space. The entries to the competition are quite interesting, in fact, so I've posted some of them, below, focusing on one particular project at the end of this post (so please scroll down if you've already read about this competition). First, then, here's the old Vatnsmýri airport and its earthen geometry of intersecting runways. This is the site – star-like and stretching out to its surrounding landscapes – within which the designers had to work.   [Images: The Vatnsmýri airport grounds, Reykjavík, Iceland. Photos courtesy of the Reykjavík City Planning Committee]. [Images: The Vatnsmýri airport grounds, Reykjavík, Iceland. Photos courtesy of the Reykjavík City Planning Committee].And here are some of the project entries, which I have posted in order, from shortlisted entries through to the big prize winners – but I have selected them on the purely superficial criterion of my own visual interest. Some of these projects, including two grand prize winners, are, I'm sure, absolutely fascinating, but small JPGs of their proposals simply don't give you very much to work with. So, with genuine apologies to those designers whose work does not appear here, take a look at some of the entries.  [Image: By Alexander D'Hooghe, et al.]. [Image: By Alexander D'Hooghe, et al.]. [Image: By Antonello Boatti, Birgir Breiðdal, and Nicola Ferrara]. [Image: By Antonello Boatti, Birgir Breiðdal, and Nicola Ferrara]. [Image: By Lola E. Sheppard and Mason White]. [Image: By Lola E. Sheppard and Mason White]. [Image: By Rolf J. Teloh, et al.]. [Image: By Rolf J. Teloh, et al.]. [Image: By Thomas Forget and Jonathan F. Bell]. [Image: By Thomas Forget and Jonathan F. Bell]. [Image: By Andrés Perea Ortega, et al.]. [Image: By Andrés Perea Ortega, et al.]. [Image: By Beatriz Ramo, et al.]. [Image: By Beatriz Ramo, et al.]. [Image: By Peer T. Jeppesen, et al.]. [Image: By Peer T. Jeppesen, et al.]. [Image: By Belinda Kerry, Andrew Lee, Fiona Harrisson, and Blake F. Bowers]. [Image: By Belinda Kerry, Andrew Lee, Fiona Harrisson, and Blake F. Bowers]. [Image: By Manuel Lodi, et al.]. [Image: By Manuel Lodi, et al.]. [Image: By Jeff Turko, Guðjón Þór Erlendsson, Dagmar Sirch, and Sibyl Trigg]. [Image: By Jeff Turko, Guðjón Þór Erlendsson, Dagmar Sirch, and Sibyl Trigg]. [Image: By Graeme Massie, Stuart Dickson, Alan Keane, and Tim Ingleby]. [Image: By Graeme Massie, Stuart Dickson, Alan Keane, and Tim Ingleby].And now I want to zero-in on one of the projects. Here, then, is a quick exploration of a shortlisted entry by Lola E. Sheppard and Mason White of the Toronto-based firm Lateral Architecture.  [Image: By Lola E. Sheppard and Mason White]. [Image: By Lola E. Sheppard and Mason White].Their project begins, we read, "by establishing 'no-build' zones or public landscapes. The figure of the runway is used to identify three primary axes. Each former runway is converted into a 'greenway' that uses a quality of the city as its primary trait."   [Images: By Lola E. Sheppard and Mason White]. [Images: By Lola E. Sheppard and Mason White].The greenways are then given new programs, or functions, which the architects define as Ecology, Recreation, and Production. The Ecology greenway, for instance, "is conceived of as a dot-matrix of cellular ecosystems, organic rooms, landscape surfaces of hard and softscape, gardens and pools."   [Images: By Lola E. Sheppard and Mason White]. [Images: By Lola E. Sheppard and Mason White].The Production greenway, which I like quite a lot, has been "treated as a barcode of interdependent production activities, with changing densities of fish farming, greenhouses for fruit, vegetable and flower production, allotment gardens, markets and tree farming." Fish Farms are located on the western end of the strip and serve both a local populace through an adjacent market and an international market with a distribution port. A series of greenhouses line the edges of the existing runway and create cluster of outdoor 'rooms.' Interspersed are modest community garden and farm plots which subdivide the space and integrate the adjacent communities into the strip. A second market, proposed at the triangle intersection, serves to sell these vegetables and flowers to the Reykjavik community. A dense forest continues the barcode and creates wood for the initial construction phases. This forest gains more permanence in successive phases and is used to absorb carbon dioxide and offer oxygen to the new development. All of which sounds great to me. There is even a "network of geothermal pipes" that does something or other for the fish farms. But how spectacular to live in a city full of greenhouses! Re-formatting architectural interiors to grow fruit. You wander around at night through certain districts of your city watching strange plants grow behind glass. The air smells alive. It's quiet. And there are fewer cars – because entire streets have been blocked off and replaced with greenhouses, freeing up former parking lots to become orchards and small croplands. Microfarms. Perhaps new coastal rivers even cut through the city, engineered by heroic valves tucked away beneath the streets, irrigating various neighborhoods and responding to lunar tides. What used to be highway flyovers are now orange groves, and over there, in the abandoned airport, fields of medicinal flowers now grow.  [Image: By Lola E. Sheppard and Mason White]. [Image: By Lola E. Sheppard and Mason White].On a vaguely related note, meanwhile, my own description here has reminded me of the discovery last winter that listening to birdsong might actually improve mental health. So imagine ten thousand new birds up in the trees of this greenhouse city as the sun begins to rise over huge warehouses walled with angled glass panes, like something out of analytical Cubism, and you're just sitting there eating toast with local honey, listening to morning birdsong, surrounded by plants.  [Image: By Lola E. Sheppard and Mason White]. [Image: By Lola E. Sheppard and Mason White].In any case, the final greenway proposed by this project would be a "recreation corridor" in which "spaces for formal and informal activities" will be built, including "soccer fields, running tracks, basketball, tennis and volleyball, local schools and playgrounds."  [Image: By Lola E. Sheppard and Mason White]. [Image: By Lola E. Sheppard and Mason White].The greenways will all knit together and criss-cross, following the buried logic of the old runways. In ten years' time, you can take your kids out into the middle of a forest and say: "They used to land planes here..." (All of these images are also available in a small Flickr set).

The structural engineers over at Hyder Consulting have announced that they are planning what will be, by an overwhelming margin, the world's tallest skyscraper, coming in at double the height of the Burj Dubai – or very nearly one vertical mile. The firm has "confirmed that the tower would be located in the Middle East region," we're told, "but would not give any further details." So is it just a media stunt? I decided, nonetheless, to alter an old BBC diagram about the world's tallest buildings to give myself a sense of what this might mean, size-wise; the results appear above. I have to assume that the building's actual profile will not resemble what I've created... but you never know. Note the comparative size of the Empire State Building. (News item spotted on Archinect – where we're reminded of Frank Lloyd Wright's Mile High Illinois project).

[Image: A submission to London's recent Bat House Project by Andrew Brown, Gareth Jones, and James Falconer; view larger]. [Image: A submission to London's recent Bat House Project by Andrew Brown, Gareth Jones, and James Falconer; view larger].The above project, by Andrew Brown, Gareth Jones, and James Falconer, proposes "a home for bats in London." It was produced for the Bat House Project, the stated aim of which was to highlight "the potential for architects, builders, home-owners and conservationists to work together to produce wildlife-friendly building design. It connects the worlds of art and ecology to encourage public engagement with ecology issues." This is pretty old news, of course – but I just saw this particular design yesterday, and I have a thing for architecture delivered from the sky, dropped off by what appear to be military helicopters. I'd like to see a short, inspirational video in which a dozen U.S. families are standing in a cul-de-sac. Everyone's hair is whipping to and fro – and there are helicopter gunships flying overhead, dropping off complete Toll Brothers homes. The houses are ready for inhabitation, complete with pots and pans, pillows and sheets. There are five bedrooms, and three and a half baths. Wives are hugging wives; men are cheering. The slow motion thud of helicopter blades fills all audible space. The video ends.

[Image: 3d-printing new deltas into existence, courtesy of New Scientist]. [Image: 3d-printing new deltas into existence, courtesy of New Scientist].If we could divert certain segments of the Lower Mississippi River into subsidiary canals, we'd "create up to 1000 square kilometres of new wetlands between New Orleans, Louisiana and the Gulf of Mexico, forming a vital storm surge buffer against hurricanes," New Scientist reports. It's prosthetic deltas as the future of landscape design: The proposed diversion would cut breaches into a levee some 150 km south of New Orleans, Louisiana, and 30 km above where the river empties into the Gulf of Mexico. With the diversions in place, flooding would cause the river to empty into shallow saltwater bays on either side of the river, releasing sediment-rich water to produce new deltas. As Robert Twilley of Louisiana State University phrases it: "You keep the sediment within the coastal boundary current that keeps it running along the shoreline, whereas now it gets ejected into the Gulf." This thus constructs "new delta land" instead of uselessly shooting all that sediment over the continental shelf – and that newly aggregated land, like a literal land bank, will help protect New Orleans and its surrounding parishes from future hurricane damage.  [Image: Courtesy of the Center for Land Use Interpretation]. [Image: Courtesy of the Center for Land Use Interpretation].But I'm left wondering if this might not also imply some new form of 3D printing, using river sediments as ink and machine-controlled deltas as printheads: you open certain valves, gates, and locks according to predetermined schedules, in some massive inhabitable printhead complex run by the local flood control board, and you can print deltaic land into existence, at will, moving peninsulas here and there, forming islands, atolls, archipelagos, all through the directed sediments of the Mississippi River... It'd be a kind of horizontal spray-gun, bringing terra nova into existence. For what it's worth, meanwhile, my wife and I have co-authored a chapter in a forthcoming book called What Is A City?, published by the University of Georgia Press, in which we talk at great length about these sorts of post-Katrina hydrological projects – including the use of genetically-modified marshgrasses to anchor artificially dredged fill, in a more or less complete deterrestrialization of the earth's surface. Or, to use a bad pun, you could say that these projects are literally outlandish. Finally, don't miss the show up now at the Center for Land Use Interpretation, Birdfoot: Where America's River Dissolves Into The Sea. The end of the Mississippi River Delta – the Birdfoot – is a national landscape of disintegration, a fractal labyrinth of dendritic channels, a blend of water and earth, bisected and rerouted by linear, engineered forms of pipeline canals and levees. The people who live and work here, beyond the reach of roads, do so tenuously, in a delicate, disappearing place that is battered by hurricanes, and eroding into the sea. The closing date for the exhibition is not available.

[Image: Photo by Doug McKinlay, courtesy of The Observer]. [Image: Photo by Doug McKinlay, courtesy of The Observer]."Deep in the Arctic Circle," we read, there is "a remarkable hotel made up of fishing huts on a frozen lake." Of course, you don't check in for the modern amenities: after all, the hotel is more like "a cross between camping and pottering in a garden shed," Doug McKinlay writes. Instead, you check in to watch the Northern Lights.   [Images: By Doug McKinlay, courtesy of The Observer]. [Images: By Doug McKinlay, courtesy of The Observer].Called the Abisko Ark Hotel, it's located 250km north of the Arctic Circle, on Sweden's Lake Tornetrask. "Guests are expected to bring essentials such as thermal underwear, fleeces and woolly hats, but the hotel provides thick outerwear and heavy snowmobile boots." Each hut "is about six meters square and sleeps three comfortably on single beds. The best part is that by each bed is a resealable hole in the wooden floor, allowing guests to fish from the comfort of their down-filled sleeping bags."

[Image: Photo by Ben Nilsson of Big Ben Productions]. [Image: Photo by Ben Nilsson of Big Ben Productions].These photos of the ICEHOTEL in Jukkasjärvi, Sweden, just popped up everywhere. I think this might literally be one of the most beautiful hotels in the world. It makes me wonder if architects might someday CNC-mill buildings out of glaciers. "You sleep in a thermal sleeping bag on a special bed of snow and ice, on reindeer skins," we read. "You are awakened in the morning with a cup of hot lingonberry juice at your bedside."  [Images: All photos by Ben Nilsson of Big Ben Productions]. [Images: All photos by Ben Nilsson of Big Ben Productions]."Breakfast buffet, morning sauna and towels [are] included," of course – and there's a restaurant on site, made from ice, serving "whitefish roe, venison and reindeer, cloudberries and arctic raspberries. All transformed into tasty delicacies guaranteed to please the most discerning gourmet." This year, the hotel was built with collaborative input from students of Stockholm's Royal Institute of Technology.  So how is the ICEHOTEL actually built? "The building process starts in mid-November," the hotel's managers explain, "when the snow guns start humming and large clouds of snow start to drift along the Torne River." The snow is sprayed on huge steel forms and allowed to freeze. After a couple of days, the forms are removed, leaving a maze of free-standing corridors of snow.  [Image: Photo by Ben Nilsson of Big Ben Productions]. [Image: Photo by Ben Nilsson of Big Ben Productions].They continue: In the corridors, dividing walls are built in order to create rooms and suites. Ice blocks, harvested at springtime from Torne River, are now being transported into the hotel where selected artists from all over the world start creating the art and design of the persihable material. These "corridors of snow," of course, could be used to form instant cities almost anywhere; with a few "snow guns" and a bunch of "huge steel forms," you too could build an ICEHOTEL – or an ICECITY, or an ICETOWN, just waiting to be inhabited. It's architecture as controlled phase transition: coaxing temporary forms out of what wants to be liquid. To mis-paraphrase Sanford Kwinter paraphrasing Alfred North Whitehead, we might say that this is an example of Misplaced Concreteness.  [Image: By Ben Nilsson of Big Ben Productions]. [Image: By Ben Nilsson of Big Ben Productions].In any case, here are some photos of the construction process, documenting how the hotel was made – and here is a price list, in Swedish krona, should you want to book a few nights. Send me, please! (Also covered by Dezeen).

[Image: A cargo elevator beautifully shot by po1yester]. [Image: A cargo elevator beautifully shot by po1yester].Further proof that elevators have been ignored for too long in contemporary building design – after all, they are moving rooms and could be put to use as something other than mere vertical transport through architectural space – even Harrods, the London department store, is (temporarily) updating its lifts. According to the Guardian, Harrods is about to open Lifted, "the world's first exhibition to be displayed in elevators" (a wild over-statement that is, in fact, wrong). The elevator-based exhibition will include work by "Oscar-winning composer Michael Nyman and visual artist Chris Levine." Levine's "Sight" lift will feature a light sculpture using Swarovski crystals and lasers to immerse passengers in mesmerising patterns once the doors close. Nyman's "Sound" composition aims to trigger feelings of confinement. The "Smell" lift, designed by Aroma Co, emits smells such as pomegranate and fresh laundry via wall-mounted buttons, while the tactile "Touch" lift was devised by the Royal National Institute for the Blind.

The "Sixth Sense" lift, however, created by author and "cosmic ordering" expert Bärbel Mohr, encourages customers to send wishes to the universe and "reconnect with their inner self". On an only vaguely related note, meanwhile, I'd be curious to see if you could invert the expected volumetric relationship between stationary floors and moving elevators in a high-rise. In other words, if elevators usually take up, say, one-twentieth of a building's internal space, could you flip that ratio – and end up with just one stationary floor somewhere hanging out up there inside a labyrinth of elevators? You have a job interview on that one, lone floor in a half an hour's time – but you can't find the place. You're moving from elevator to elevator, going down again and stopping, then stepping across into another lift that takes you up four floors higher than you'd expected to be – before you're going down again, confused. You hear other elevators when you're not moving, and it's impossible to locate yourself amidst that system of moving rooms. The only floors you ever exit onto are simply other elevators. Then, through a coincidence of open lift doors, forming a temporary corridor through space, front and back doors open, stretching off through eight cars at a time, you glimpse the meeting room that you're even right then supposed to be sitting down in for an interview... and you see people there waiting... but the doors all close and you're back on the ground floor in no time. You hear machines, cables, whirring gears.  [Image: Elevator Buttons by Vancouver-based photographer Jason Pfeifer]. [Image: Elevator Buttons by Vancouver-based photographer Jason Pfeifer].Stunned, perhaps mesmerized, and already addicted to that well-machined state of vertically nomadic groundlessness, you smile, hit the UP button, and start again. (Thanks, Nicky!)

Will the city of Amsterdam soon build "a labyrinth city" beneath its canals?

[Image: A new underground city for Amsterdam, by Zwarts & Jansma]. [Image: A new underground city for Amsterdam, by Zwarts & Jansma].

Maybe so.

According to World Architecture News, "Newspapers around Europe have been reporting on the scheme, which requires the city's canals to be drained to allow the construction of a vast underground mixed-use complex beneath."

[Image: Underground Amsterdam by Zwarts & Jansma]. [Image: Underground Amsterdam by Zwarts & Jansma].

It's an idea by Zwarts & Jansma architects, whose plans includes excavating "a range of underground facilities... at various levels below the city."

[Images: Zwarts & Jansma]. [Images: Zwarts & Jansma].

Apparently, the project is even technically feasible: The Dutch capital may be unique as its geology lends itself to the technical feasibility of this scheme. Moshé Zwarts explained, "Amsterdam sites on a 30-metre layer of waterproof clay which will be used together with concrete and sand to make new walls. Once we have resealed the canal floor, we will be able to carry on working underneath while pouring water back into the canals. It's an easy technique and it doesn't create issues with drilling noises on the streets." But does that mean Amsterdam should really build it? For instance, World Architecture News is quite opposed to the project – yet the Telegraph reports that "the project has been approved by Amsterdam's city council. Construction work, lasting up to 20 years, is expected to begin in 2018."

[Image: Zwarts & Jansma]. [Image: Zwarts & Jansma].

Maybe they should build it and use it as a penal colony. Imagine the escape attempts – trying to get out of the earth.

(Thanks to Alex Haw for the tip!)

|

|

[Image: "Abandoned equipment stands in the snow near the top of an underground tunnel that was once used to drain mine water." Photo by Kevin Moloney for The New York Times].

[Image: "Abandoned equipment stands in the snow near the top of an underground tunnel that was once used to drain mine water." Photo by Kevin Moloney for The New York Times]. [Image: "Abandoned equipment stands in the snow near the top of an underground tunnel that was once used to drain mine water." Photo by Kevin Moloney for The New York Times].

[Image: "Abandoned equipment stands in the snow near the top of an underground tunnel that was once used to drain mine water." Photo by Kevin Moloney for The New York Times].

[Image: The Zoo de Vincennes, by

[Image: The Zoo de Vincennes, by  [Image: Landscapes in the Zoo de Vincennes, designed by

[Image: Landscapes in the Zoo de Vincennes, designed by  [Image: The Zoo de Vincennes, by

[Image: The Zoo de Vincennes, by  [Image: More landscapes in the Zoo de Vincennes, by

[Image: More landscapes in the Zoo de Vincennes, by  [Images: Zooscapes by

[Images: Zooscapes by  [Image: The Zoo de Vincennes, by

[Image: The Zoo de Vincennes, by  [Image: The Zoo de Vincennes, by

[Image: The Zoo de Vincennes, by  [Image: The Zoo de Vincennes, by

[Image: The Zoo de Vincennes, by

[Images: The Vatnsmýri airport grounds, Reykjavík, Iceland. Photos courtesy of the

[Images: The Vatnsmýri airport grounds, Reykjavík, Iceland. Photos courtesy of the  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By

[Images: By

[Images: By

[Images: By

[Images: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  The structural engineers over at

The structural engineers over at  [Image: A submission to London's recent

[Image: A submission to London's recent  [Image: 3d-printing new deltas into existence, courtesy of

[Image: 3d-printing new deltas into existence, courtesy of  [Image: Courtesy of the

[Image: Courtesy of the  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by

[Images: By

[Images: By  [Image: Photo by Ben Nilsson of Big Ben Productions].

[Image: Photo by Ben Nilsson of Big Ben Productions]. [Images: All photos by Ben Nilsson of Big Ben Productions].

[Images: All photos by Ben Nilsson of Big Ben Productions]. So how is the ICEHOTEL actually built?

So how is the ICEHOTEL actually built?  [Image: Photo by Ben Nilsson of Big Ben Productions].

[Image: Photo by Ben Nilsson of Big Ben Productions]. [Image: By Ben Nilsson of Big Ben Productions].

[Image: By Ben Nilsson of Big Ben Productions]. [Image: A cargo elevator beautifully shot by

[Image: A cargo elevator beautifully shot by  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: A new underground city for Amsterdam, by

[Image: A new underground city for Amsterdam, by  [Image: Underground Amsterdam by

[Image: Underground Amsterdam by

[Images:

[Images:  [Image:

[Image: