|

|

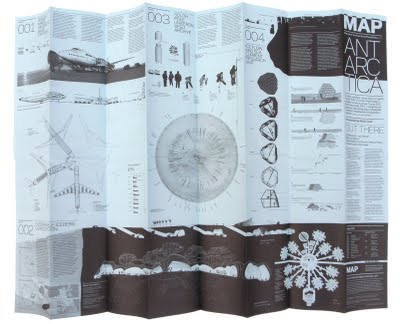

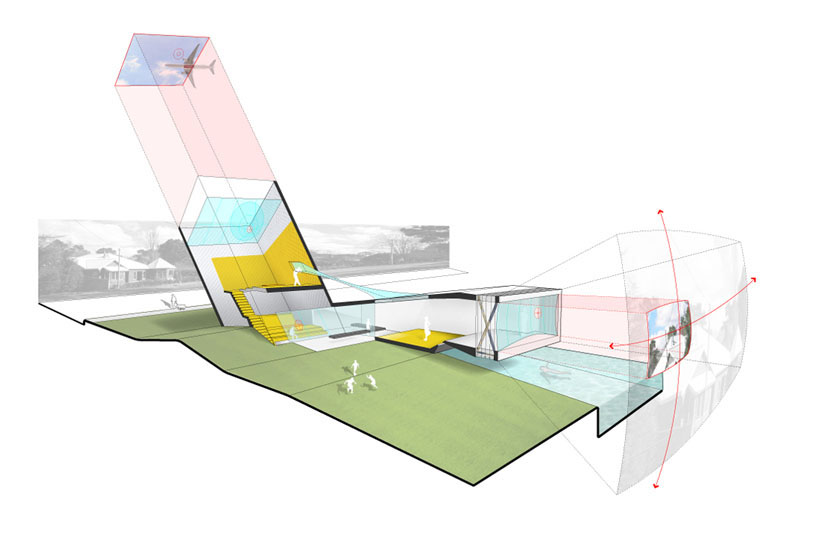

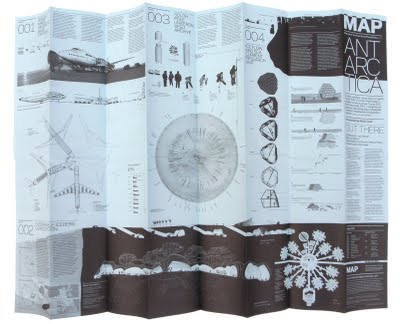

As many people who attended my book launch this past weekend in New York will already know, I had on hand a fantastic new publication by architect David Garcia: the Manual of Architectural Possibilities, or M.A.P.   [Images: M.A.P. by David Garcia]. [Images: M.A.P. by David Garcia].I had the pleasure of meeting David back in Sweden earlier this month at the ASAE conference; David's presentation and our subsequent conversation – ranging from the architecture of déjà vu and haunted house novels to the possibility of sonic archives and the work of David Gissen – were more than enough to show that he is pushing forward through some incredibly interesting ideas and is already someone worth keeping an eye on now, not just in the future. He's even just completed a cool children's playground in suburban Denmark. Issue One of M.A.P. – or poster #1, really, as it all unfolds into a double-sided A1 sheet – is about Antarctica.  [Image: M.A.P. by David Garcia]. [Image: M.A.P. by David Garcia].Open the poster up and there are habitats excavated directly from the ice, their dimensions and size based on the carving radius of industrial digging machines; there are seed archives entombed throughout the polar glaciers, marked only by GPS; there are abandoned airplanes all hooked together into a grounded megastructure and reused as research labs; there is a catalog of snow crystal geometry; and there is a photo-survey of exploratory housing for visiting scientists. Look for M.A.P. at an architecture bookstore near you, or get in touch with David Garcia Studio directly to order some copies. M.A.P. #2 – which is, incidentally, open for suggestions – will be about "Archives." And future M.A.P.s are impossible not to daydream about: a M.A.P. for prisons, gardens, earthquakes, architecture school, the moon...

[Image: The wastewater treatment plant at Roseville, California, unrelated to the poem discussed below]. [Image: The wastewater treatment plant at Roseville, California, unrelated to the poem discussed below].For nearly four years now, without access to a good library, I've been looking for a poem called "Staines Waterworks" by the English poet Peter Redgrove; it's impossible to Google and, though I knew I'd actually photocopied it for myself nearly a decade ago, I had apparently lost the photocopies. But, then, amidst the weird rolling peaks of recovery and amnesia that come with cleaning through your old books and papers in the family basement, I found a sheaf of old photocopies in a box about an hour ago – and inside it was "Staines Waterworks" by Peter Redgrove. The poem is incredible for a variety of reasons; but its most basic impulse is to describe the water purification plant at Staines, west London (the hometown of Ali G), as a kind of previously overlooked alchemical process. It is water "in its sixth and last purification" that "leaps from your taps like a fish," Redgrove writes. Rainwater gross as gravy is filtered from

Its coarse detritus at the intake and piped

To the sedimentation plant like an Egyptian nightmare,

For it is a hall of twenty pyramids upside-down

Balanced on their points each holding two hundred and fifty

Thousand gallons making thus the alchemical sign

For water and the female triangle. The poem is a stimulatingly odd collision of occult – many might say openly New Age – symbols and present-day civic infrastructure. In the process, it raises some amazing and fascinating questions of how we might more interestingly interpret the built structures surrounding us. Redgrove describes the movement of water through its various steps of industrial filtration, saying that it "reverberates... like some moon rolling / And thundering underneath [the] floors," passing through a "windowless hall of tides." It is a surrogate astronomy, surging through the replicant gravity of pumps and steel holding tanks. The processed river water is then decanted, surveilled by automata, and "treated by poison gas, / The verdant chlorine which does not kill it." Beyond life, it is pushed through "anthracite beds," where Water meets Earth in an engineered encounter between the elements.  [Image: A wastewater treatment plant in Macao, via Wikimedia, unrelated to the poem discussed in this post]. [Image: A wastewater treatment plant in Macao, via Wikimedia, unrelated to the poem discussed in this post].Later, in what Redgrove might call its fourth purification, the water at Staines flows past an underground structure that resembles "a castle," complete with "turrets / And doors high enough for a mounted knight in armour / To rein in." Dials here are read "as though [they are] the castle library." There are very few people in attendance,

All are men and seem very austere

And resemble walking crests of water in their white coats,

Hair white and long in honourable service. Civic water-filtration takes on the air of a Druidic ritual, with bespoke costumes, arcane electrical equipment, and the dull roar of the inhuman echoing both above and below. Thames Water or, for that matter, Brita become strangely occult organizations obsessed with ritual actions and weird geometries, like something out of Aleister Crowley. It is sustainability by way of the B.P.R.D.Redgrove's poem – and I refer only to "Staines Waterworks" here, as I am not that familiar with his other work – shows the transformative power of description: give something an unexpected context and whole new, extraordinarily vibrant worlds can be created. This is more important, more lasting, and more interesting than much of what passes for architectural criticism today. Finally, the baptized liquid at Staines reaches a point of biological and chemical clarity, after which it is re-introduced to the city through a labyrinth of pipework that extends in wild curlicues, a machinic Thames beneath western London. Scalded, filtered, purified, made artificially natural and ready for drinking, it is water born again for future uses.

[Image: New York's Storefront for Art and Architecture, photographed (and beautifully renovated) by Rieder Smart Elements]. [Image: New York's Storefront for Art and Architecture, photographed (and beautifully renovated) by Rieder Smart Elements].I owe a huge thanks to everyone who came out on Saturday for the event in New York City – in particular, the speakers who added so much to the proceedings. Karen Van Lengen, Jace Clayton, Richard Mosse, Mason White, Patrick McGrath, and Lebbeus Woods all brought enthusiasm and interest to their participation, and Joseph Grima and the staff at Storefront for Art and Architecture were phenomenally generous, patient, and organized with their time – and likely to break-out huge spreads of Syrian food at a moment's notice. Alan Rapp, editor of The BLDGBLOG Book, was also on hand to offer some incredibly appreciated, and economically quite timely, thoughts on publishing, blogs, architectural speculation, and more. It was also great simply to see so many old friends, going back nearly a decade and a half, and finally to meet people whose work I've written about on BLDGBLOG, in Dwell, and in publications elsewhere. From future car engines sound-designed by DJ /rupture to a tomb for Albert Einstein, via childhoods lived in the shadows of psychiatric institutions, student "sound lounges," photographic surveys of remote air disasters, and infrastructural ice floes, it was a gigantic Saturday, and I was thrilled to be a part of it. So thanks for coming out, thanks for participating, and thanks for saying hello!

[Image: Quarantine facility and hospital ward on Swinburne Island, in the NYC archipelago]. [Image: Quarantine facility and hospital ward on Swinburne Island, in the NYC archipelago].It's been an extremely eventful month since Edible Geography and BLDGBLOG teamed up to announce "Landscapes of Quarantine," an eight-week, intensive, independent design studio to be hosted this fall in New York City; its brief is to create original and thought-provoking design projects that explore the spatial implications of quarantine. The results of the studio will then be the subject of an exhibition at Storefront for Art and Architecture in spring 2010. The practice of quarantine extends far beyond questions of epidemic control and pest containment strategies to touch on urban planning, geopolitics, international trade, ethics, immigration, and more. In the early twentieth century, for example, "quarantine lines in Africa offered a clear and politically useful demarcation for new 'international' borders between Sudan and Egypt," as historian Alison Bashford points out in her book Medicine at the Border. From Boccaccio's Decameron and disinfected mail protocols to bio-secure airlocks, plant smuggling, and Matt Leacock's Pandemic boardgame, quarantine is a fertile territory for architects and designers to explore. You can read more about the studio here. Over the past few weeks, we have been blown away by the quality (and even quantity) of applicants interested in the studio. Indeed, narrowing the pool down to a manageable group of participants has been a very tricky process. We have been concerned all along with achieving a usefully diverse mix of backgrounds, media, and individual strategies of approach, while holding numbers low enough that the studio can still function as a weekly discussion group.  [Image: U.S. "Federal and State Isolation and Quarantine Authority," updated January 18, 2005]. [Image: U.S. "Federal and State Isolation and Quarantine Authority," updated January 18, 2005].We are now excited to announce a truly amazing list of participants: —Joe Alterio — Illustrator, Animator, and Comic Book Artist (http://joealterio.com/)

Joe Alterio is an illustrator, animator, comic creator, and artist, interested in narrative structure, collective creativity, and the physical manifestations of story-telling. Joe has been at the forefront on using new technology to push forward the graphic narrative medium, from his early 2004 mobile comic The Basic Virus to his most recent work with Robots and Monsters. Alterio's work has appeared in the Boston Globe, Rolling Stone, Boing Boing, Drawn!, The BLDGBLOG Book, and many other publications.  [Image: Joe Alterio, from Robots and Monsters]. [Image: Joe Alterio, from Robots and Monsters].—Elizabeth Ellsworth and Jamie Kruse – Artists, smudge studio (http://smudgestudio.org/)

Elizabeth Ellsworth and Jamie Kruse are co-directors of smudge studio, a collaborative, non-profit media arts studio based in Brooklyn. Ellsworth is Associate Provost of Curriculum and Learning and Professor of Media Studies at The New School. Her recent book, Places of Learning: Media, Architecture, Pedagogy is about the aesthetics of mediated learning environments. Kruse is an artist, independent scholar, and freelance graphic designer.

—Scott Geiger — Writer, Architecture Research Office (http://www.aro.net/)

Scott Geiger is the recipient of a Pushcart Prize for fiction. A contributor to magazines such as The Believer and Conjunctions, Geiger also writes for Architecture Research Office, a 2009 Finalist for the National Design Award for Architecture. As a Cleveland native, schemes to rescue America’s postindustrial cities stalk his work.

—Yen Ha and Michi Yanagishita — Architects, Front Studio (http://www.frontstudio.com/) and "ladies who lunch" (http://lunchstudio.blogspot.com/)

Yen Ha and Michi Yanagishita are principals of Front Studio Architects, named one of the “world’s 50 hottest young architectural practices” by Wallpaper magazine. Their work has been featured internationally in Icon, AD: Cities of Dispersal, and the New York Times, and it was recently featured in the London Yields exhibition at the Building Centre in London. The Invisible Gate, their competition entry in the 2005 Gdansk International Outdoor Art Gallery, is currently under construction.   [Image: Front Studio, Farmadelphia]. [Image: Front Studio, Farmadelphia].—Katie Holten — Artist (http://www.katieholten.com/)

Katie Holten has exhibited widely in Europe and the United States, and, in 2003, she represented Ireland at the Venice Biennale. She currently has a solo exhibition at The Bronx Museum of the Arts and a public artwork installed in the Bronx, called the Tree Museum. Holten was born in Dublin, Ireland, and is now based in New York City.

—Jeffrey Inaba — Architect, INABA Projects (http://www.inabaprojects.com/), Director, C-LAB (http://c-lab.columbia.edu/), and Editor, Volume Magazine (http://volumeproject.org/)

Jeffrey Inaba is the Director of C-Lab, an architecture, policy and communications think tank at Columbia University‘s GSAPP, and he is Features Editor of Volume Magazine. With Rem Koolhaas, Inaba co-directed the Harvard Project on the City, a research program investigating contemporary urbanism and planning worldwide. Before starting INABA, he was a principal of AMO, the research consultancy founded by Koolhaas. Inaba has also taught at UCLA, Harvard, and SCI-Arc, and he lectures worldwide.

—Ed Keller — Architect and Filmmaker, AUM Studio (http://www.aumstudio.org/)

Ed Keller is a designer, professor, writer, “media architect,” and former professional rock climber. He is co-founder with Carla Leitao of AUM Studio, an architecture and new media firm based in New York and Lisbon. Keller is an Associate Professor at Parsons School of Design, and he has taught at Columbia's GSAPP, SCI-Arc, Pratt, the University of Pennsylvania, and more. Keller's work has been featured in ANY, AD, Wired, Metropolis, Assemblage, among others.

—Mimi Lien — Set Designer (http://www.mimilien.com/)

Mimi Lien is a designer of sets and environments for theater, dance, and opera. After studying architecture at Yale University, she began making paintings, installations, objects, and designs for performance. Her work has been seen at The Joyce and The Kitchen, and she is a recipient of a 2007-2009 NEA/TCG Career Development Program award.  [Image: Mimi Lien, from a set design for Samuel Beckett's Endgame]. [Image: Mimi Lien, from a set design for Samuel Beckett's Endgame].—Richard Mosse — Photographer (http://www.richardmosse.com/)

Richard Mosse is an Irish photographer based in New York. He travels extensively with the assistance of a Leonore Annenberg Fellowship in the Performing and Visual Arts. Recent forays have taken him to Gaza, the Yukon Territories, and Iraq. Mosse has a forthcoming solo show at Jack Shainman Gallery, opening on November 19th, and new video work will be exhibited at Barcelona's Ca L'Arenas, in a year-long exhibition cycle, investigating war and its representations.  [Image: Richard Mosse, ruined swimming pool at the palace of Uday Hussein, Jebel Makhoul, Iraq]. [Image: Richard Mosse, ruined swimming pool at the palace of Uday Hussein, Jebel Makhoul, Iraq].—Daniel Perlin — Sound Designer, Perlin Studios (http://danielperlin.net/)

Daniel Perlin is a New York-based artist and sound designer. Perlin operates across media, creating video, objects, installations and performances. His work has been heard at Chelsea Art Museum, the Whitney Biennial 2006, D’Amelio Terras, TN Probe Tokyo, Temporary Contemporary Gallery, the Centre Pompidou, and BCA (Beijing), as well as in such films as Kelly Reichardt’s Old Joy, Errol Morris’s Fog Of War and Phil Morrison’s Junebug.

—Thomas Pollman — Architect, NYC Office of Emergency Management (http://www.nyc.gov/oem and http://www.thomaspollman.com/)

Thomas Pollman is an architect and amateur cartographer based in New York City. He currently works in the Geographic Information Systems Division at the NYC Office of Emergency Management, where he works to enhance situational awareness for first responders through the deployment of geospatial technologies. Pollman is a registered architect in the State of New York.

—Kevin Slavin — Urban Games Designer, Area/Code (http://areacodeinc.com/)

Kevin Slavin is managing director and co-founder of Area/Code. Working with media companies, museums, brands, and foundations around the world, Area/Code focuses on games with computers in them. Their work frequently extends game systems into the real world—and the other way around. Prior to founding Area/Code, Slavin was an artist and an advertising executive.

—Brian Slocum — Architect, Polshek Partnership Architects (http://www.polshek.com/)

Brian Slocum is the recipient of a 2008 grant from the New York State Council on the Arts for ad hoc infrastructures, a design research project focusing on the deployment of scaffolding and alternatives for its spatial exploitation. Slocum was a contributor to Pamphlet Architecture #23 and is currently an Associate at Polshek Partnership Architects.

—Amanda Spielman — Graphic Designer, Graphomanic (http://www.graphomanic.net/) and SpotCo (http://www.spotnyc.com/)

Amanda Spielman is a graphic designer at SpotCo, a New York-based design studio and ad agency that specializes in creating artwork for Broadway theater. Previously, she spent seven years in editorial design. Her work has appeared in The Design Entrepreneur, Fingerprint, Graphis, STEP, SPD, and metropolismag.com. Spielman graduated from the MFA Design program at the School of Visual Arts, and holds a BA from Vassar College.  [Image: Amanda Spielman, Island of New Ephemera]. [Image: Amanda Spielman, Island of New Ephemera].—Lebbeus Woods — Architect, Author, and Educator (http://lebbeuswoods.wordpress.com/ and http://lebbeuswoods.net/)

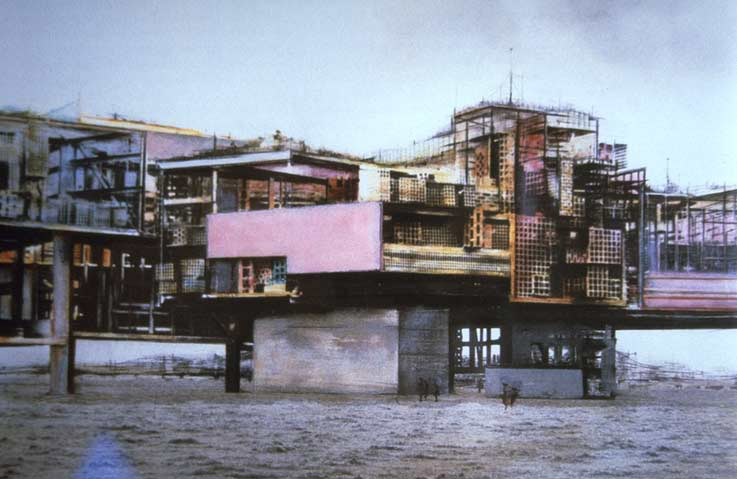

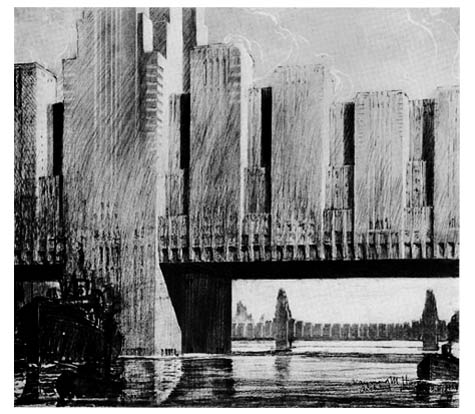

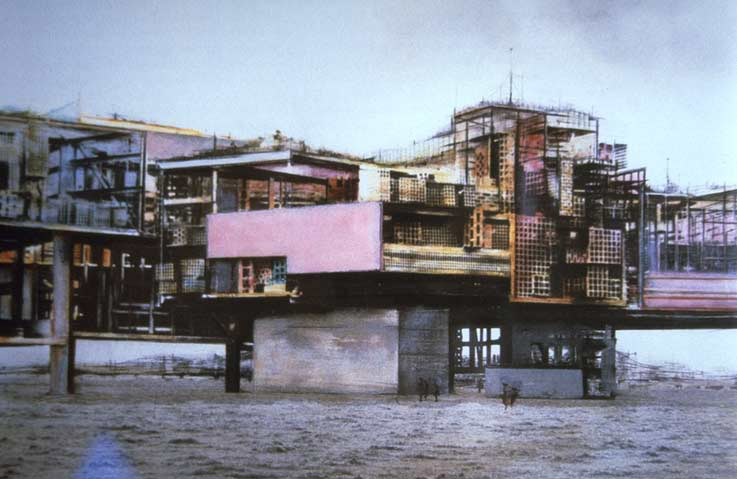

Lebbeus Woods is an architect and educator. He is co-founder of RIEA.ch, an institute devoted to the advancement of experimental architectural thought and practice, and author of Pamphlet Architecture #6 and #15, among countless other articles and books. His works are held in private and public collections worldwide, including the Museum of Modern Art and the Austrian Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna. Woods has received the Progressive Architecture Award for Design Research, the American Institute of Architects Award for Design, and the Chrysler Award for Innovation in Design. He is currently Professor of Architecture at The Cooper Union in New York City.  [Image: Lebbeus Woods, from a film treatment for Underground Berlin]. [Image: Lebbeus Woods, from a film treatment for Underground Berlin].It's hard to overstate how honored we are to work with practitioners of this caliber; we look forward to eight solid weeks of inspiring conversations and even more interesting work. Expect frequent updates throughout the fall – in particular, during the week of October 5th, when we will begin to publish, both on Edible Geography and on BLDGBLOG, a series of original interviews with quarantine historians, public health policy experts, biosafety consultants, and more, placing quarantine into its unpredictably extensive context. By making the studio discussions and our own research material public, we hope that anyone who has been inspired by the studio brief – and by the subject matter of quarantine – will be inspired to pursue their own projects, outside the necessarily limited walls of the studio.

[Image: The Mobile Fabrication Unit by Gramazio & Kohler, soon to be building at Storefront for Art and Architecture]. [Image: The Mobile Fabrication Unit by Gramazio & Kohler, soon to be building at Storefront for Art and Architecture].Some things to read on a Monday afternoon: —Architect Bjarke Ingels of BIG dominates the stage at TED. I was able to walk around BIG's recently completed Mountain Dwellings in Copenhagen the other week, as part of an amazing drive around what felt like all of Denmark with Johan Hybschmann and Nicola Twilley. The building's now-famous parking garage, we suggested only half-jokingly, would make an amazing venue for an architecture conference: its terraced parking decks overlook and focus upon a kind of inadvertent auditorium. Drive-in films, drive-in lectures, drive-in pirate radio concerts – it's too fantastic a space not to try. —Lebbeus Woods offers a glimpse of a film he outlined, designed, and later co-wrote with Olive Brown, called Underground Berlin. It involves a disillusioned architect, a missing twin brother, neo-Nazi activities in the divided city, metallic underground tunnels connecting east to west, and "a top-secret underground research station rumored to be somewhere beneath the very center of Berlin." There are even rogue planetary scientists investigating "the tremendous, limitless geological forces active in the earth." Woods's graphic presentation of the idea is incredible, and absolutely worth a very long look. —Meanwhile, farmers in the UK have been asked "to implement measures which would reverse the UK-wide decline in skylark numbers." This means shaving small rectangular plots into the midst of productive cropland, because "rectangular uncropped patches in cereal fields allow skylarks to forage when crops become too dense for them." We will prepare our landscapes for other species. —Is your iPod maxing out the U.S. electrical grid? Perhaps it doesn't matter: New Scientist looks at how to short-circuit the grid altogether – and would-be saboteurs the world over are still taking furious notes. Alternatively, just follow the fantastic On The Grid series by Adam Ryder and Brian Rosa to see where the electrical network really goes. — New Scientist also scanned beneath the south polar glaciers to find " Antarctica's hidden plumbing" – and, as it happens, "the continent's secret water network is far more dynamic than we thought." —Ruairi Glynn's new book, Digital Architecture: Passages Through Hinterlands is now out; it documents Glynn's related exhibition. —Moving online, New York's Architectural League has redesigned its website – joining the Canadian Centre for Architecture, who also redesigned their own site earlier this summer. —Back in England, the BBC reports that pigs are being used "to help restore" parts of Worcestershire's historic Wyre Forest. This comes at the same time that Cairo has realized that its absurd slaughter of every pig in the city last spring in order to guard against swine flu has led to an extraordinary garbage crisis. "The pigs used to eat tons of organic waste," the New York Times reports. "Now the pigs are gone and the rotting food piles up on the streets of middle-class neighborhoods like Heliopolis and in the poor streets of communities like Imbaba." Meanwhile, Edible Geography points our attention to the fascinating labyrinth of subsidiary products made from the bodies of dead pigs; welcome to " Pig Futures." —On io9 Matt Jones suggests that " the city is a battlesuit for surviving the future," and he cites Archigram, Kevin Slavin, Dan Hill, Warren Ellis, the architecture of sci-fi, William Gibson, and much more to make his point. Speaking of Warren Ellis, Icon magazine recently published a long conversation between Warren, Francois Roche, and myself; you can check it out on Flickr. —Were artificial hills, henges, and monumental earthworks a kind of " prehistoric sat nav" installed across the British landscape? And does this same question seem to be asked at least once every few years? —The 2009 Solar Decathlon approaches. —Gramazio & Kohler's Mobile Fabrication Unit will arrive soon at New York's Storefront for Art and Architecture. Between October 5 and October 27, it will be busy assembling "the first temporary public installation to be built on site by an industrial robot in New York." Then, however, on Halloween, it will become possessed by incomprehensible forces from the Precambrian depths of the city, and, in a horrifying night of thunderous brickwork, it will wall off the island of Manhattan forever... Necessitating a script for Ghostbusters III as written by Lebbeus Woods. More links soon.

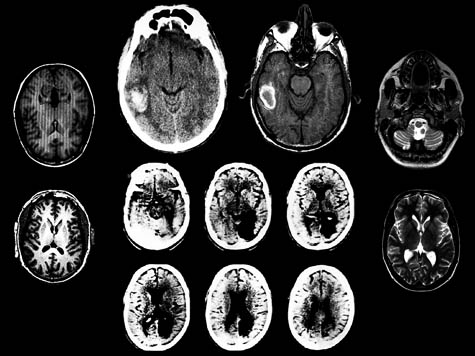

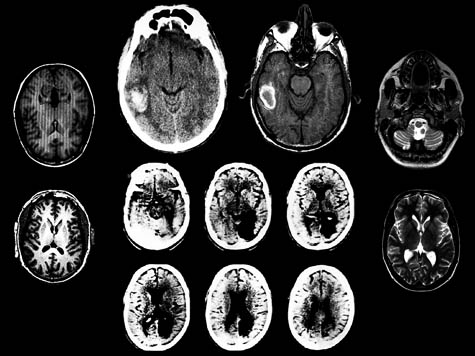

First thing tomorrow morning, I will be presenting at Ruairi Glynn's Digital Architecture London conference, alongside Neil Spiller, Murray Fraser, and Alan Penn. Our topic is "Digital Architecture & Space." Anticipating a day filled with formal discussions, I'll be speaking – albeit briefly – about what might be called the psychiatric effects of simulated environments. Specifically referring to the U.S. military's Virtual Iraq project, I want to bring into the discussion the idea that "digital space" can be used for therapeutic purposes.  [Image: Brains]. [Image: Brains].To quote at length from a fascinating article in The New Yorker about the use of virtual reality as a treatment for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: P.T.S.D. is precipitated by a terrifying event or situation—war, a car accident, rape, planes crashing into the World Trade Center—and is characterized by nightmares, flashbacks, and intrusive and uncontrollable thoughts, as well as by emotional detachment, numbness, jumpiness, anger, and avoidance. [A recently returned soldier from Iraq's] doctor prescribed medicine for his insomnia and encouraged him to seek out psychotherapy, telling him about an experimental treatment option called Virtual Iraq, in which patients worked through their combat trauma in a computer-simulated environment. The portal was a head-mounted display (a helmet with a pair of video goggles), earphones, a scent-producing machine, and a modified version of Full Spectrum Warrior, a popular video game. The purpose of discussing this is to look beyond formal analyses of digital architecture and virtual space, and to focus instead on their psychiatric possibilities. That is, what if you found out that your M.Arch thesis project was not just a really cool building that everyone in your studio loved, but that it had psychiatric effects, inducing either panic, calm, or, for that matter, déjà vu, in the people that witnessed its on-screen animation? Put another way, what if your renderings cured Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder? With only a slight shift in emphasis, could you produce a building project that used the techniques of digital architecture to create an elaborate spatial memory system – a kind of RHINO mnemonics – that neurologically stimulated the act of remembering? Of course, the use of architectural space as a road toward mental self-improvement, so to speak, is not at all new. A memory palace, for instance, is the art of remembering something by associating it with specific spatial details in a fantasy architectural structure, and this idea goes back at least to Cicero. So is there a way to discuss the impact of digital design on architecture, with all of its implications of cinematic immersion and real-time animation, without getting stuck on questions of form? How might we discuss digital architecture's impacts on things like memory – and can we do so in the context of experimental psychiatry and so-called exposure therapy? I should add that each speaker will only be presenting for about five minutes – so the above remarks will be quite short, before turning into a much more general panel discussion.

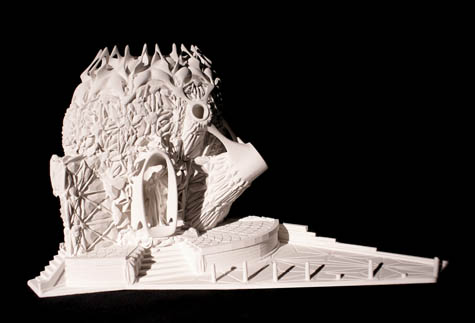

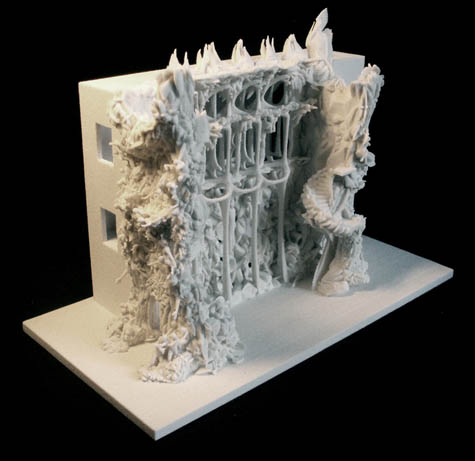

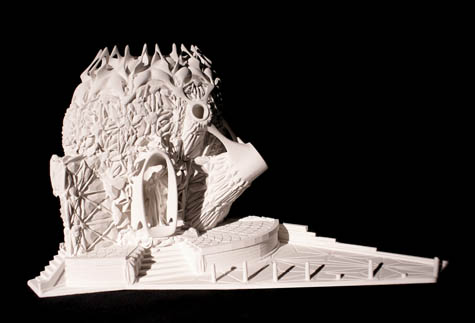

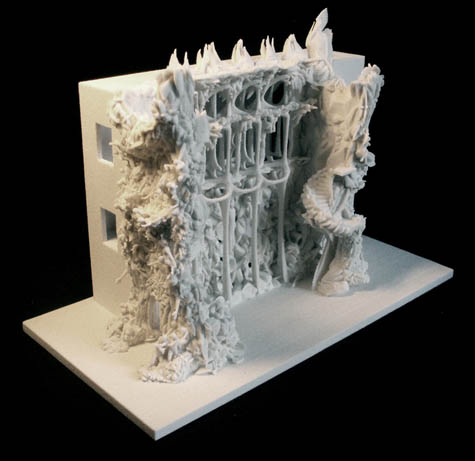

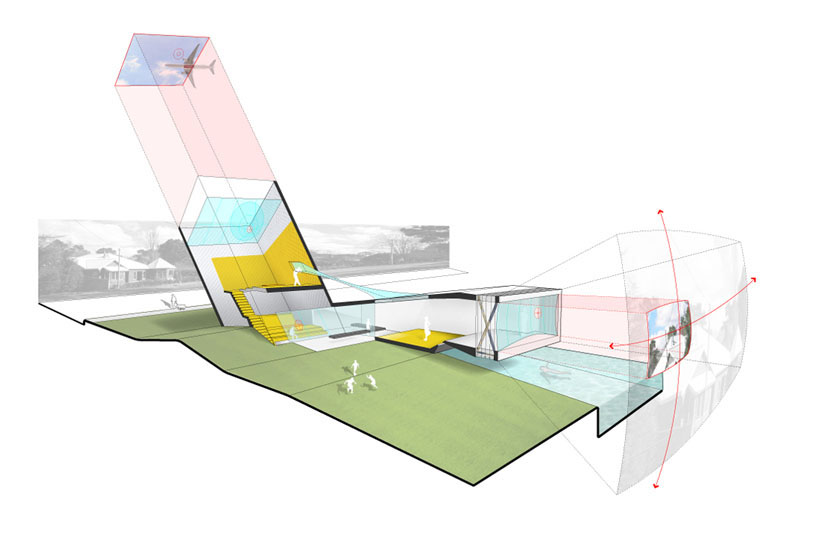

[Image: Yousef Al-Mehdari]. [Image: Yousef Al-Mehdari].A few weeks ago I mentioned some 3D-printed work by Yousef Al-Mehdari, a student at the Bartlett School of Architecture. That work is now pictured here, in a proposal for a site on the island republic of Malta.  [Image: Malta, just south of Sicily, in the exact center of the image]. [Image: Malta, just south of Sicily, in the exact center of the image].The project explores religious ritual and the human body, alongside an interest in "transitory sculptures," processional routes, and a kind of body-futurist rediscovery of architectural ornament. Vortices of limbs ossify into cathedrals; overlapping anatomies become windows and valves. Al-Mehdari suggests that a careful – even mathematically exact – study of human bodily movement could serve as a basis for generating new types of architectural form. As if we could take conic sections through Merce Cunningham, say, and turn the resulting diagrams into churches.   [Images: Yousef Al-Mehdari]. [Images: Yousef Al-Mehdari].It's the Visible Human Project as building typology: Vesalius meets Vitruvius in an era of computed tomography and RHINO.  [Images: The Visible Human Project]. [Images: The Visible Human Project].The use of the human body as a generator for architectural ornament reminds me, in an admittedly tangential way, of the " cadaver cathedral" by Jeff VanderMeer – the description of which is worth quoting in full: Where the sculptures of saints would have been set into the walls, there were instead bodies laid into clear capsules, the white, white skin glistening in the light – row upon row of bodies in the walls, the proliferation of walls. The columns, which rose and arched in bunches of five or six together, were not true columns, but instead highways for blood and other substances: giant red, green, blue, and clear tubes that coursed through the cathedral like arteries. Above, shot through with track lighting from behind, what at first resembled stained-glass windows showing some abstract scene were revealed as clear glass within which organs had been stored: yellow livers, red hearts, pale arms, white eyeballs, rosaries of nerves disembodied from their host. In any case, what's also interesting in Al-Mehdari's proposal is that this seems to be pitched more as a scooping-out, or milling, of the inside of an existing building. The main chapel and nave of a church on Malta are simply scraped, shaved, and replaced with Al-Mehdari's bodycode-geometry.  [Images: Yousef Al-Mehdari]. [Images: Yousef Al-Mehdari].This further implies, however, that this project might be materially realizable in stone. The ongoing and obvious, but nonetheless absurdly under-discussed problem with today's architectural interest in NURBs, algorithms, Voronoi tiling, parametric rhizo-phylo-archi-bio-futuro-spatiality and so on is that, yes, we can render vast and sprawling webs that consume whole cities, crawling across roofs and down streets through well-drawn tendons, arches, and amorphous sci-fi musculatures – but if all of it then gets built out of pink metal or red auto-painted aluminum that lasts for less than ten months in the wind, rain, and sun, then no matter how much your renderings might look like Tomorrowland, within weeks everything you've built will be indistinguishable from photo-degraded ruins of the early 1970s. That is, no one is talking about weathering. And it's not a trivial exercise, I would suggest, to imagine, for instance, Zaha Hadid's collected built works re-realized in sandstone: not because this is an earnest material suggestion for Hadid, but because, as a thought-exercise, such alternatives might help architects to realize that their designs could be better served by the use of other materials. All of which is a long way of saying that, to construct a new church of anatomical horror and to do so out of stone, as Al-Mehdari seems to be suggesting, is a fascinating idea. And it's a spatial idea that he explores through multiple incarnations of the resulting structure; Al-Mehdari's obvious facility with a 3D printer makes these illustrations of the idea quite exciting.    [Images: Yousef Al-Mehdari]. [Images: Yousef Al-Mehdari].It's also a seriously interesting question: could we hook up milling machines to the existing interiors of cathedrals all over the world and reshape them, in situ, without adding a thing – simply installing new insides through abrasion? Geometrically unprecedented statuary emerges from the vaults of Chartres. Westminster Abbey is reduced through bandsaws to a superterranean catacomb of interlaced saints. The following minor structural unit, meanwhile, seems more like a prized fossil found in the mountains of western China than an architectural building-block for a Mediterranean religious site.  [Image: Yousef Al-Mehdari]. [Image: Yousef Al-Mehdari].And the final two images here are more like nautiloids taken from the abyssal plains – bio-spatial artifacts with benthic resonance, we might say, like something Philip Beesley might use if he was hired to design an artificial reef.   [Images: Yousef Al-Mehdari; it's Jacques Cousteau with a 3D printer, by way of Leviathan and Mike Mignola]. [Images: Yousef Al-Mehdari; it's Jacques Cousteau with a 3D printer, by way of Leviathan and Mike Mignola].Al-Mehdari's models and diagrams are more interesting than my own speculations, however. They will also be on display next month in London, alongside work by another student from the Bartlett, Yaojen Chuang; that exhibition kicks off on October 5th at the dreamspace gallery.

[Image: By Daniel Dendra of anOtherArchitect]. [Image: By Daniel Dendra of anOtherArchitect].To produce this new tea table, Berlin-based designer Daniel Dendra of anOtherArchitect explains that he used sound recordings taken from the streets of Cairo to generate CNC-milling patterns – thus creating one of the most complex joins I've ever seen in carpentry. In Dendra's own words, he "recorded sound-snips from intersections in the city to generate a furniture piece."  [Image: By Daniel Dendra of anOtherArchitect]. [Image: By Daniel Dendra of anOtherArchitect].The acoustically-inspired topography fills the underside of the table, which meets flush and perfectly with the base (where Dendra has carved the exact opposite surface). It is the silence, so to speak, for the other surface's noise.   [Images: By Daniel Dendra of anOtherArchitect]. [Images: By Daniel Dendra of anOtherArchitect].Of course, if you get bored of drinking tea, or you simply don't like the table, you can just separate the top from its base – and you've got a readymade milled noise-map of Cairo.

I mentioned this about a month ago... but it's nearly here: on Saturday, September 26, I'll be hosting a daylong series of public talks and live interviews at Storefront for Art and Architecture in New York, featuring many of the people whose work appears in The BLDGBLOG Book. We've organized a stellar line-up of speakers, going from 3-6pm, and all of it will be followed by drinks.

[Image: The Mix House by Joel Sanders Architect, Karen Van Lengen/KVL, and Ben Rubin/Ear Studio, as mentioned in The BLDGBLOG Book]. [Image: The Mix House by Joel Sanders Architect, Karen Van Lengen/KVL, and Ben Rubin/Ear Studio, as mentioned in The BLDGBLOG Book].

The complete schedule of presentations appears below; it's free and open to the public. I'll be introducing my own book around 6pm, but then we can all have a coffee or a glass of wine (or whatever's around), and enjoy a Saturday evening in New York. I'd love to say hello, if you can make it. Copies of Patrick McGrath's novels will be available for purchase, as well, and it's a great opportunity to get them signed – in fact, if you already own a copy of The BLDGBLOG Book, or if you're thinking of getting one, bear in mind that you can score at least three signatures on the Autographs page that night...

So, again, that's Saturday, September 26, from 3pm to about 8pm, at Storefront for Art and Architecture in New York City. Here's a map.

And thanks, by the way, for reading the blog, for being interested in the ideas presented here, for participating in some fantastic comments threads over the years, for all the tips for further reading/viewing/visiting/etc., and just for sticking around in general. I don't mean to get misty-eyed, but I appreciate it, more than you might know. It's not often that one runs into other people interested in things like bioluminescent urban ornaments or haunted telephone systems or rentable basement mazes or even " learning landscapes" – as many a negative commenter here has made clear. So, to the people who have been having fun with this website along with me: thanks.

[Image: From Sietch Nevada by Matsys; renderings by Nenad Katic]. [Image: From Sietch Nevada by Matsys; renderings by Nenad Katic].

Andrew Kudless of Matsys recently proposed an extraordinary desert city of semi-subterranean terraces inspired by the novel Dune.

The images are fantastic, and the project description hooked me right away:

In Frank Herbert’s famous 1965 novel Dune, he describes a planet that has undergone nearly complete desertification. Dune has been called the “first planetary ecology novel” and forecasts a dystopian world without water. The few remaining inhabitants have secluded themselves from their harsh environment in what could be called subterranean oasises. Far from idyllic, these havens, known as sietch, are essentially underground water storage banks. Water is wealth in this alternate reality. It is preciously conserved, rationed with strict authority, and secretly hidden and protected. The rest of the project combines an interest in drought hydropolitics in the U.S. southwest with the speculative architecture of "underground water banks."

[Image: From Sietch Nevada by Matsys; renderings by Nenad Katic]. [Image: From Sietch Nevada by Matsys; renderings by Nenad Katic].

Continuing to quote at length:

Although this science fiction novel sounded alien in 1965, the concept of a water-poor world is quickly becoming a reality, especially in the American Southwest. Lured by cheap land and the promise of endless water via the powerful Colorado River, millions have made this area their home. However, the Colorado River has been desiccated by both heavy agricultural use and global warming to the point that it now ends in an intermittent trickle in Baja California. Towns that once relied on the river for water have increasingly begun to create underground water banks for use in emergency drought conditions. However, as droughts are becoming more frequent and severe, these water banks will become more than simply emergency precautions. Accordingly, Kudliss suggests that "waterbanking" will become "the fundamental factor in future urban infrastructure in the American Southwest."

In this context, I would unhesitatingly recommend Marc Reisner's classic book Cadillac Desert – the first hydrological page-turner I've ever read – as well as James Lawrence Powell's recent Dead Pool: Lake Powell, Global Warming, and the Future of Water in the West (which I reviewed for The Wilson Quarterly earlier this year). Those two books are ideal references for Matsys's project, as they each supply countless examples of hubristic, quasi-imperial waterbanking projects – projects that might still be functioning today but that are doomed, the authors convincingly show, to eventual dehydration.

Powell, in particular, offers genuinely disturbing descriptions of the looming silt-deposits that have accumulated behind the dams of the American west, amongst often extraordinarily poetic overviews of these dams' inevitable failure. “One day every trace of the dams and their reservoirs will be gone," Powell writes, "a few exotic grains of concrete the only evidence of their one-time existence.”

[Image: Matsys's Sietch Nevada as seen from above; renderings by Nenad Katic]. [Image: Matsys's Sietch Nevada as seen from above; renderings by Nenad Katic].

In any case, the proposal seen here is "an urban prototype," we read, "that makes the storage, use, and collection of water essential to the form and performance of urban life."

A network of storage canals is covered with undulating residential and commercial structures. These canals connect the city with vast aquifers deep underground and provide transportation as well as agricultural irrigation. The caverns brim with dense, urban life: an underground Venice. Cellular in form, these structures constitute a new neighborhood typology that mediates between the subterranean urban network and the surface level activities of water harvesting, energy generation, and urban agriculture and aquaculture. However, the Sietch is also a bunker-like fortress preparing for the inevitable wars over water in the region. Check out the full project on Matsys's own website – and, while you're there, the entire project database is worth a spin.

(Spotted on Architecture MNP. And read Dune!)

[Image: The Bay Line by Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello; modular additions can be seen bolted on from below. Read the project PDF]. [Image: The Bay Line by Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello; modular additions can be seen bolted on from below. Read the project PDF].Combining Rails to Trails, William Gibson's Virtual Light, and the same repurposed-preservation strategies behind New York's High Line, Bay Area architects Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello have called for stabilizing the disused – and soon to be entirely dismantled – portion of the Bay Bridge. They would then turn it into a pedestrianized urban park and outdoor sports attraction.  [Image: The Bay Bridge and its replacement; on the right is the piece that Rael San Fratello would like to see stabilized. Image via Wikipedia]. [Image: The Bay Bridge and its replacement; on the right is the piece that Rael San Fratello would like to see stabilized. Image via Wikipedia].And if it works for the Bay Bridge, they suggest, it could work for other disused bridges elsewhere. "This proposal seeks to repurpose abandoned and closed bridges as sites of potential for parks, cultural centers and housing," the architects write in the project's accompanying PDF. In the process, they hope "to demonstrate the potential for re-purposing historic American bridge infrastructure as possible sites for sustainable urban housing and linear parks." The immense load capacity of rail bridges allows for the support of program beyond that of parks, suggesting the urbanization of bridges. While the current economic climate suggests a surplus of housing, the economic reality also suggests a push towards urbanization and often the “affordable” housing constructed in suburban environments, which encroaches on the rural, is not what is needed. Instead, by using abandoned bridges in urban areas, we are creating opportunities for sustainable low-cost housing within the urban realm—creating the potential for creative speculation among housing developers by expounding upon the nascent potential of a layered housing-park-bridge typology. While, on one level, this simply side-steps the immense financial implications associated with structurally maintaining these bridges, and, on another level, it bears an unfortunate resemblance to Boris Johnson's recent – if not necessarily well-received – call for an inhabitable bridge across the Thames, it does also kick-start a conversation about what we might be able to do with the massive pieces of civic infrastructure that dot the U.S. and are currently scheduled for replacement and demolition.    [Images: (top) Tennis court, bicycle path, and observation module; (middle) Outdoor auditorium; (bottom) swimming pool on the Bay Line by Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello]. [Images: (top) Tennis court, bicycle path, and observation module; (middle) Outdoor auditorium; (bottom) swimming pool on the Bay Line by Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello]. And, I have to admit, it would simply be cool: Imagine housing, recreational and cultural facilities connected to a continuous, lushly planted, green strip, floating above the water—an aerial garden, as the city's newest park through which you could walk and wander and enjoy the most spectacular views of the bay. Of course, critics like James Howard Kunstler might suggest that reusing rail infrastructure – or, in this case, highway infrastructure – as anything other than a rejuvenated national rail service is " decadence at its purest," it is surely just as decadent to watch as functional pieces of infrastructure rot on all sides, as you sit there with your arms crossed, waiting for the nation's taxpayers to agree with your views on reuse.     [Images: Other habitable bridge: (top) Florence's Ponte Vecchio; (second) a painting by Peter Jackson of "Old London Bridge"; (third and bottom) Constant's New Babylon]. [Images: Other habitable bridge: (top) Florence's Ponte Vecchio; (second) a painting by Peter Jackson of "Old London Bridge"; (third and bottom) Constant's New Babylon].In any case, as someone who literally never enjoyed driving across the Bay Bridge for seismic-safety reasons, I have to point out that this proposal still comes with its own set of earthquake-related issues. I was interested, however, to read in the Economist just this week that "there are few safe places to ride out an earthquake. Surprisingly, though, a recently constructed bridge is often one of them." Engineers have become good at designing bridges that are earthquake-resistant enough to preserve the lives of those caught crossing when a quake strikes. The problem is that the bridge is often unusable afterwards. Nonetheless, if you had put millions of dollars' worth of landscape and housing onto a bridge that was then left abandoned and "unusable" after an earthquake, it would be a very foolhardy investment, indeed.  [Image: Final render of the Bay Line by Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello]. [Image: Final render of the Bay Line by Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello].But what of bridges in non-seismic zones? In Sydney, for instance, due to the peninsular nature of walks along Cremorne Point and through Kirribilli, there are places where the Sydney Harbor Bridge appears not to be crossing over water at all, but standing over the rooftops of the city, anchored into the neighborhood. It looks more like a new kind of inland megastructure, strung above the streets and restaurants, like something designed by Perdido Street Station-era China Miéville, than a harbor bridge. An industrial cathedral of exposed ribs and steel tension lines, arcing up into the skyline. So what if you hung houses from it? What amazing typologies of bolt-on architectural prosthetics could we create, if bridges were aerial foundations and they carried not cars or locomotives but schools and piazzas? In fact, I'm reminded of this unexpectedly inspiring – structurally speaking – proposal by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, which sought to string the suspension cables of a new pedestrian bridge from inside the nearby buildings of a rebuilt Leamouth Peninsula (click through to their image gallery for more).  [Image: A proposal for London's Leamouth Peninsula by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill]. [Image: A proposal for London's Leamouth Peninsula by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill].Returning to Rael San Fratello's Bay Line, though, there are obviously still huge issues associated with the unusually catastrophic nature of structural failure when it comes to inhabitable bridges, as well as the financially prohibitive needs of regular maintenance, but treating suspension bridges simply as another type of district in the city is an undeniably interesting urban idea. (Via Streetsblog SF and Ronald Rael. Meanwhile, Rael's recently published book Earth Architecture is an excellent and thoughtful survey of earthen structures across the world and throughout building history; Rael's old school blog, megablog, is also worth a read for its eye-popping and often literally world-altering architectural ambitions).

[Image: "Endothelium" by Philip Beesley & Hayley Isaacs]. [Image: "Endothelium" by Philip Beesley & Hayley Isaacs].I mentioned a recent issue of Mark Magazine the other day, but I deliberately saved one of the articles for a stand-alone post later on. That article was a long profile of the work of Philip Beesley, a Toronto-based architect and sculptor, whose project the " Implant Matrix" BLDGBLOG covered several years ago. In issue #21 of Mark, author Terri Peters describes several of Beesley's projects, but it's the " Endothelium" that really stood out (and that you see pictured here).  [Image: "Endothelium" by Philip Beesley & Hayley Isaacs]. [Image: "Endothelium" by Philip Beesley & Hayley Isaacs].Peters refers to Beesley's work as a "lightweight landscape of moving, licking, breathing and swallowing geotextile mesh" – a kind of pornography of ornament, or the Baroque by way of David Cronenberg. "Inspired by coral reefs," she continues, "with their cycles of opening, clamping, filtering and digesting," Beesley's biomechanical sculpture-spaces are "immersive theatre environments" in which "wheezing air pumps create an environment with no clear beginning or end." I'm reminded of the penultimate scene in James Cameron's film Aliens, when Ripley (Sigourney Weaver) meets the alien "queen." The queen is laying eggs, we see, through a gigantic, semi-prosthetic, peristaltically-powered external ovarian sac – and the scene exemplifies the encounter with the grotesque in all its H.R. Giger-influenced, sci-fi extremes. Put another way, if organisms, too – not just buildings – can reach a point of ornamental excess, then James Cameron's aliens are perhaps exhibit number one.  [Images: Screen grabs from James Cameron's Aliens]. [Images: Screen grabs from James Cameron's Aliens].In any case, Beesley's work is a fascinating hybrid of advanced textile design, geostructural modeling, and rogue biology experiment. Peters's descriptions of the "Endothelium" are worth quoting at length: [The structure consists of] a field of organic "bladders" that are self-powered and that move very slowly, self-burrowing, self-fertilizing and are linked by 3D printed joints and thin bamboo scaffolding. The bladders are powered using mobile phone vibrators and have LED lights. It works by using tiny gel packs of yeast which burst and fertilize the geotextile. This latter detail – "using tiny gel packs of yeast which burst and fertilize the geotextile" – brings to mind something at the intersection of an improvised explosive device (or IED) and a green roof: you hire Philip Beesley to design a landscape-machine for installation atop a new building downtown, and, over the course of many decades, it vibrates, yeast-bursts, rotates, crawls, and grows through extraordinary cycles of grotesque architectural fertility. A solar-powered landscape of mold and microroots, generating its own soil. Within a few years, the original sculpture it all came from is gone, archaeologically undetectable beneath the vitality of the forms that have consumed it. One wonders what Philip Beesley would think of the mushroom tunnel of Mittagong.   [Images: "Endothelium" by Philip Beesley & Hayley Isaacs]. [Images: "Endothelium" by Philip Beesley & Hayley Isaacs].Elsewhere in the article, Peters writes: Endothelium is an automated geotextile, a lightweight and sculptural field housing arrays of organic batteries within a lattice system that might reinforce new growth. It uses a dense series of thin "whiskers" and burrowing leg mechanisms to support low-power miniature lights, pulsing and shifting in slight increments. Within this distributed matrix, microbial growth is fostered by enriched seed-patches housed within nest-like forms, sheltered beneath the main lattice units. I'm a bit rhetorically stuck on "between" statements, I'm afraid, but it's as if Beesley's work falls somewhere between a loaf of sourdough bread and a sculpture by Jean Tinguely.  [Image: "Endothelium" by Philip Beesley & Hayley Isaacs]. [Image: "Endothelium" by Philip Beesley & Hayley Isaacs].I'm curious, meanwhile, if you could bury a Philip Beesley sculpture in the woods of rural England somewhere, and allowed it to articulate new ecosystems slowly, over the cyclic course of generations. In fact, I'm reminded of an article in the New York Times last week, spotted via mammoth, in which we learn that two abandoned landfills in Brooklyn have since been used as unlikely foundations for new ecosystems: In a $200 million project, the city’s Department of Environmental Protection covered the Fountain Avenue Landfill and the neighboring Pennsylvania Avenue Landfill with a layer of plastic, then put down clean soil and planted 33,000 trees and shrubs at the two sites. The result is 400 acres of nature preserve, restoring native habitats that disappeared from New York City long ago. "Once the plants take hold," the article adds, "nature will be allowed to take its course, evolving the land into microclimates." But what if those weren't landfills down there but sculptures by Philip Beesley? Strategically sown seed-patches and gel packs of yeast wait underground for new roots to rediscover them. It's living geostatuary, buried beneath the surface of the earth – a kind of extreme agriculture, with soil-preparation by Philip Beesley.   [Images: "Endothelium" by Philip Beesley & Hayley Isaacs]. [Images: "Endothelium" by Philip Beesley & Hayley Isaacs].I'd genuinely like to see what Beesley might do if he was hired by, say, a NASA R&D program dedicated to terraforming other planets. Could you fly a modular, self-unfolding Philip Beesley sculpture into the depths of radiative space, land it on a planet somewhere, and watch as revolting pools of bacteriological mucus begin to coagulate and form new fungi? Beesley's whiskered vibrators begin to shiver with signs of piezoelectric life, as small crystals surrounded by radio transmitters and genetically engineerined space-seed-patches imperceptibly tremble, evolving into mutation-prone "organic batteries" unprotected beneath starlight. Give it a thousand years, and vast infected forests, the width of continents, take hold. You've colonized a distant planet through architecture and yeast. For more, check out Mark Magazine's issue #21. Beesley's also got a book out, called Hylozoic Soil, that I would love to read.

|

|

[Images: M.A.P. by David Garcia].

[Images: M.A.P. by David Garcia]. [Image: M.A.P. by David Garcia].

[Image: M.A.P. by David Garcia].

[Image: The wastewater treatment plant at

[Image: The wastewater treatment plant at  [Image: A wastewater treatment plant in Macao, via

[Image: A wastewater treatment plant in Macao, via  [Image: New York's

[Image: New York's  [Image: Quarantine facility and hospital ward on

[Image: Quarantine facility and hospital ward on  [Image: U.S. "Federal and State Isolation and Quarantine Authority," updated January 18, 2005].

[Image: U.S. "Federal and State Isolation and Quarantine Authority," updated January 18, 2005]. [Image:

[Image:

[Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: Brains].

[Image: Brains]. [Image: Yousef Al-Mehdari].

[Image: Yousef Al-Mehdari]. [Image: Malta, just south of Sicily, in the exact center of the image].

[Image: Malta, just south of Sicily, in the exact center of the image].

[Images: Yousef Al-Mehdari].

[Images: Yousef Al-Mehdari]. [Images: The

[Images: The  [Images: Yousef Al-Mehdari].

[Images: Yousef Al-Mehdari].

[Images: Yousef Al-Mehdari].

[Images: Yousef Al-Mehdari]. [Image: Yousef Al-Mehdari].

[Image: Yousef Al-Mehdari].

[Images: Yousef Al-Mehdari; it's

[Images: Yousef Al-Mehdari; it's  [Image: By Daniel Dendra of

[Image: By Daniel Dendra of  [Image: By Daniel Dendra of

[Image: By Daniel Dendra of

[Images: By Daniel Dendra of

[Images: By Daniel Dendra of  [Image: The Mix House by

[Image: The Mix House by  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: Matsys's

[Image: Matsys's  [Image: "

[Image: " [Image: The Bay Line by Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello; modular additions can be seen bolted on from below. Read the project

[Image: The Bay Line by Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello; modular additions can be seen bolted on from below. Read the project  [Image: The Bay Bridge and its replacement; on the right is the piece that Rael San Fratello would like to see stabilized. Image via

[Image: The Bay Bridge and its replacement; on the right is the piece that Rael San Fratello would like to see stabilized. Image via

[Images: (top) Tennis court, bicycle path, and observation module; (middle) Outdoor auditorium; (bottom) swimming pool on the Bay Line by Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello].

[Images: (top) Tennis court, bicycle path, and observation module; (middle) Outdoor auditorium; (bottom) swimming pool on the Bay Line by Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello].

[Images: Other habitable bridge: (top) Florence's

[Images: Other habitable bridge: (top) Florence's  [Image: Final render of the Bay Line by Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello].

[Image: Final render of the Bay Line by Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello]. [Image: A proposal for London's

[Image: A proposal for London's  [Image: "

[Image: " [Image: "

[Image: " [Images: Screen grabs from James Cameron's Aliens].

[Images: Screen grabs from James Cameron's Aliens].

[Images: "

[Images: " [Image: "

[Image: "

[Images: "

[Images: "