|

|

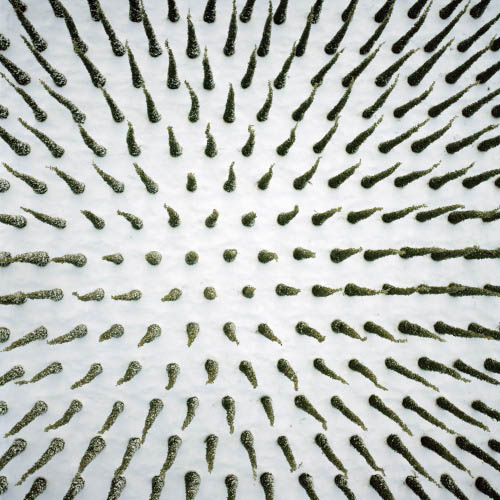

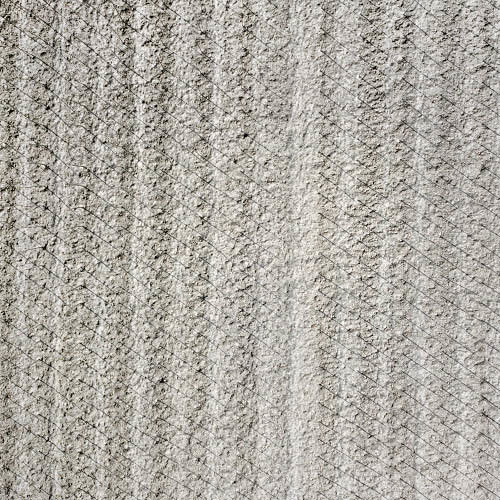

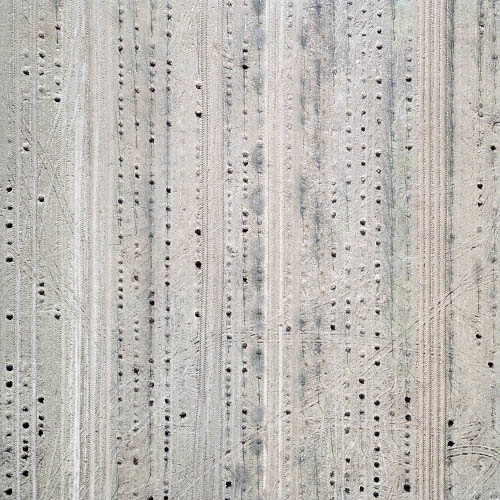

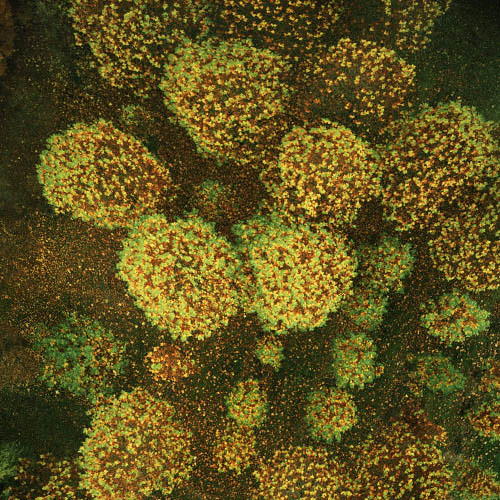

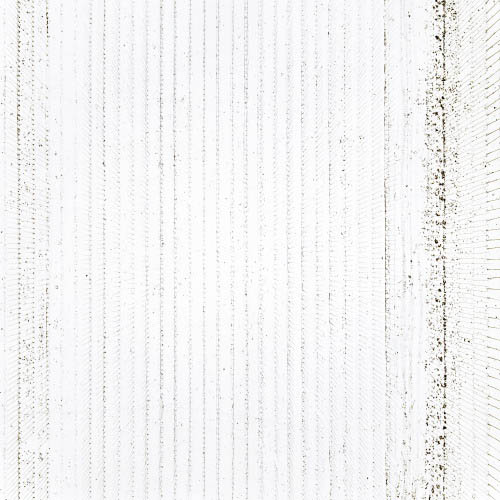

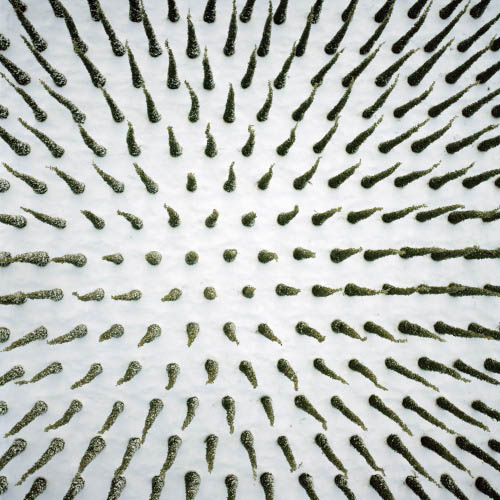

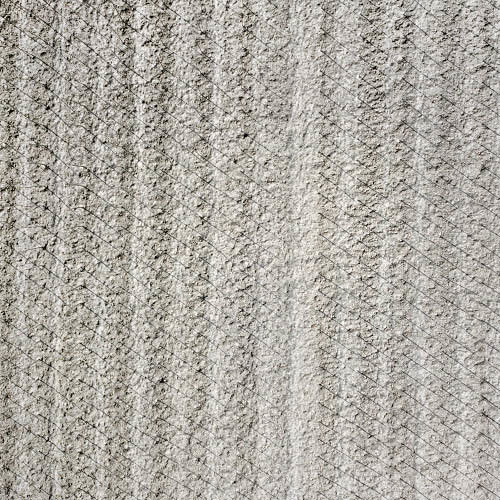

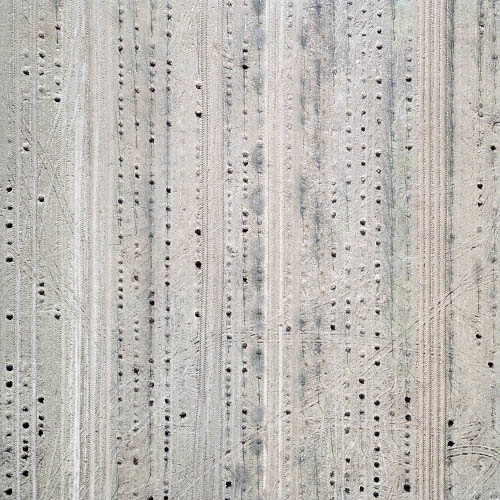

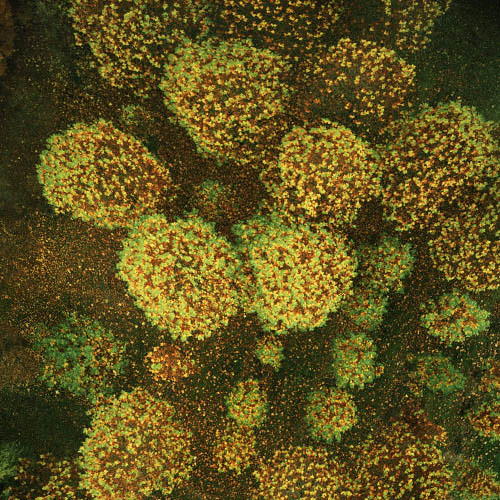

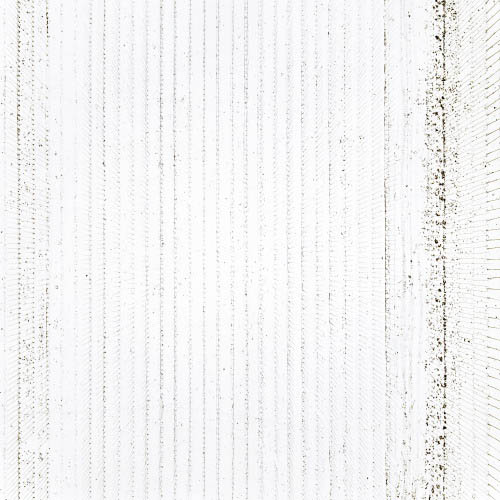

[Image: 020 by Gerco de Ruijter, 28" x 28", from Baumschule (2008-2010), courtesy of the artist]. [Image: 020 by Gerco de Ruijter, 28" x 28", from Baumschule (2008-2010), courtesy of the artist].

Dutch photographer Gerco de Ruijter recently got in touch with an extraordinary series of aerial photographs called Baumschule—some of which, he explains, were taken using a camera mounted on a fishing rod.

The series features "32 photographs of tree nurseries and grid forests in the Netherlands."

[Image: 010 by Gerco de Ruijter, 28" x 28", from Baumschule (2008-2010), courtesy of the artist]. [Image: 010 by Gerco de Ruijter, 28" x 28", from Baumschule (2008-2010), courtesy of the artist].

"How abstract can a landscape become while remaining a landscape?" de Ruijter asked himself. "I tried to find the answer to this question during extended travels, by searching for a fully natural landscape, not manmade, and lacking any cultural presence. I found these 'natural-born' sites in New Mexico—deserts formed by rocks and sand and all forms of erosion. A barren landscape, too, with scarce vegetation."

[Image: 014 by Gerco de Ruijter, 28" x 28", from Baumschule (2008-2010), courtesy of the artist]. [Image: 014 by Gerco de Ruijter, 28" x 28", from Baumschule (2008-2010), courtesy of the artist].

But this same research—a quest for a kind of inhuman authenticity of the surrounding terrain—eventually brought him to the hyper-artificial landscapes of tree farms and nurseries in the Netherlands.

[Image: 005 by Gerco de Ruijter, 28" x 28", from Baumschule (2008-2010), courtesy of the artist]. [Image: 005 by Gerco de Ruijter, 28" x 28", from Baumschule (2008-2010), courtesy of the artist].

He thus set about visually documenting what he calls "the Dutch culturally defined landscape": The Dutch landscape was efficiently drawn with functionality in mind on the drawing boards of urban and rural planners. Tulip fields, hothouses, land worked by farmers on tractors with their GPS handy. As de Ruijter goes on to explain, even though the project seeks to document "an extremely defined cultural landscape, it is the abnormalities that jump into view."

[Image: 009 by Gerco de Ruijter, 28" x 28", from Baumschule (2008-2010), courtesy of the artist]. [Image: 009 by Gerco de Ruijter, 28" x 28", from Baumschule (2008-2010), courtesy of the artist].

Returning to the original question—"How abstract can a landscape become while remaining a landscape?"—de Ruijter suggests that "all of these objects arranged to form rows create a new form of abstraction, not because of the image’s emptiness but, to the contrary, because of the presence of so many 'things,' and their patterns and rhythms," as if we could farm and harvest barcodes directly from the ground.

[Images: 007 and 032, all by Gerco de Ruijter, 28" x 28", from Baumschule (2008-2010), courtesy of the artist]. [Images: 007 and 032, all by Gerco de Ruijter, 28" x 28", from Baumschule (2008-2010), courtesy of the artist].

Indeed, "I found an enormous variety of visual elements," he adds. "They show up not just because of the different seasons, but also through the stratification of the land. Trees, soil, holes. The combination of a tight grid and the camera’s central perspective results in a distinct depth, while on a cloudy day fore and background may slide into each other."

[Image: 002 by Gerco de Ruijter, 28" x 28", from Baumschule (2008-2010), courtesy of the artist]. [Image: 002 by Gerco de Ruijter, 28" x 28", from Baumschule (2008-2010), courtesy of the artist].

To take these photos, de Ruijter used both kite photography and even "a long fishing rod."

He describes how the process worked: "On top of this rod is a 2.5" x 2.5" camera with a wide-angle lens. A self-timer is adjusted to give me enough time to telescope the rod and manoeuver the camera above the subject. The frame of the image begins in front of my own shoes and measures roughly 30' x 30'."

[Image: 001 by Gerco de Ruijter, 28" x 28", from Baumschule (2008-2010), courtesy of the artist]. [Image: 001 by Gerco de Ruijter, 28" x 28", from Baumschule (2008-2010), courtesy of the artist].

It is fascinating to see, though, when the arboreal vitality of the trees overcomes the grid they're planted in, to become fractally expressive of a different formal logic, one that exceeds any agricultural formatting of the landscape.

[Image: 028 by Gerco de Ruijter, 28" x 28", from Baumschule (2008-2010), courtesy of the artist]. [Image: 028 by Gerco de Ruijter, 28" x 28", from Baumschule (2008-2010), courtesy of the artist].

I should also point out that I recently found some great views of a tree farm on Google Maps, a strangely dot-matrix landscape that appears more cryptographic than botanical—an emergent garden of living QR codes.

[Image: 008 by Gerco de Ruijter, 28" x 28", from Baumschule (2008-2010), courtesy of the artist, a great example of how the "fore and background may slide into each other," as the photographer describes it]. [Image: 008 by Gerco de Ruijter, 28" x 28", from Baumschule (2008-2010), courtesy of the artist, a great example of how the "fore and background may slide into each other," as the photographer describes it].

Gerco de Ruijter's Baumschule series is currently on display in its entirety at the Stedelijk Museum Schiedam, where it opened last week. It closes on April 10.

[Image: Courtesy of Terremark, via the Atlantic]. [Image: Courtesy of Terremark, via the Atlantic].

Andrew Blum has a short piece up at the Atlantic today about the geography of "internet choke points," and the threat of a "kill switch" that would allow countries (like Egypt) to turn off the internet on a national scale.

After all, Blum writes, "it's worth remembering that the Internet is a physical network," with physical vulnerabilities. "It matters who controls the nodes." Indeed, he adds, "what's often forgotten is that those networks actually have to physically connect—one router to another—often through something as simple and tangible as a yellow-jacketed fiber-optic cable. It's safe to suspect a network engineer in Egypt had a few of them dangling in his hands last night.

Blum specifically refers to a high-security building in Miami owned by Terremark; it is "the physical meeting point for more than 160 networks from around the world," and thus just one example of what Blum calls an internet "choke point." These international networks "meet there because of the building's excellent security, its redundant power systems, and its thick concrete walls, designed to survive a category 5 hurricane. But above all, they meet there because the building is 'carrier-neutral.' It's a Switzerland of the Internet, an unallied territory where competing networks can connect to each other."

But, as he points out, this neutrality is by no means guaranteed—and is even now subject to change.

[Image: For a project at the Bartlett School of Architecture's Unit 11, presented and discussed at the Landscape Futures Super-Workshop, Rina Kukaj explored a series of aerial landscapes—a "purification blanket"—that would act as a distributed atmospheric filter for the city]. [Image: For a project at the Bartlett School of Architecture's Unit 11, presented and discussed at the Landscape Futures Super-Workshop, Rina Kukaj explored a series of aerial landscapes—a "purification blanket"—that would act as a distributed atmospheric filter for the city].

Two write-ups of the Landscape Futures Super-Workshop have appeared. In one, Nate Berg, writing for Domus, refers to what he calls "a new shared and experimental approach to curating" that helped to animate the super-workshop's various events. In another, Friends of the Pleistocene describe their burgeoning research project into the debris basins on the edge of the city, a "long-term project to map their locations and create a typology of their forms," which kicked off during the super-workshop.

Each debris basin "exists as a 'signaling device,'” they write. Each announces that geologic change unfolds here, right here, in continuous and unpredictable ways. Each basin also exemplifies the best human attempt to build, plan for and contain the potentially uncontainable: the material reality of geologic time and force. When flowing debris activates these basins, an incredible shape-shifting occurs: the force and materiality of geologic time actually become perceivable. Solid becomes liquid, the far becomes near, virtual becomes actual, top becomes bottom, and a precarious equilibrium loses its poise as the habitable instantly becomes uninhabitable. They cite the classic essay, “Los Angeles Against the Mountains,” also previously mentioned here on BLDGBLOG, where write John McPhee introduces us to the terrestrial instability of the ground beneath and around greater Los Angeles. In the process, he specifically describes the often bizarre spatial defenses through which houses can survive in the fallout paths of rockslides, debris slugs, and other forms of geologic "mass wasting."

[Image: Landscape Futures Super-Workshop students visit a debris dam at the top of Pine Cone Road]. [Image: Landscape Futures Super-Workshop students visit a debris dam at the top of Pine Cone Road].

The outermost suburbs of L.A. have reached what McPhee calls the “real-estate line of maximum advance” against the dark bulk of the San Gabriels—a range “divided by faults, defined by faults, and framed by them.” The San Gabriels “are nearly twice as high as Mt. Katahdin or Mt. Washington,” he points out, “and are much closer to the sea. From base platform to summit, the San Gabriels are three thousand feet higher than the Rockies.” However, they are also “disintegrating at a rate that is also among the fastest in the world.”

The San Gabriels produce, in the process, extraordinary rockslides: “On the average, about seven tons disappear from each acre each year—coming off the mountains and heading for town.” These slides are known as debris slugs, and they “amass in stream valleys and more or less resemble fresh concrete. They consist of water mixed with a good deal of solid material, most of which is above sand size. Some of it is Chevrolet size.” Debris slugs have been known to contain “propane tanks, outbuildings, picnic tables, canyon live oaks, alders, sycamores, cottonwoods, a Lincoln Continental, an Oldsmobile, and countless boulders five feet thick.” And all of it comes crashing down—frequently going right through people’s houses.

[Image: The debris dam & basin at the strikingly beautiful Deukmejian Wilderness Park]. [Image: The debris dam & basin at the strikingly beautiful Deukmejian Wilderness Park].

In the face of “this heaving violence of wet cement,” as McPhee describes it, new architectural techniques have become urgently necessary. “At least one family,” for instance, “has experienced so many debris flows coming through their back yard that they long ago installed overhead doors in the rear end of their built-in garage. To guide the flows, they put deflection walls in their back yard. Now when the boulders come they open both ends of their garage, and the debris goes through to the street.” The house becomes a mechanism through which mobile geology violently flows.

Mazes of street barriers, deflection walls, overhead doors, feeder channels, concrete crib structures—these emerging typologies are not just limited to the domestic world. The whole city’s in on it. Los Angeles County “began digging pits to catch debris,” McPhee explains, surrounding itself with a necklace of voids in order to counteract an earth that moves.

The city’s debris pits are “quarries, in a sense, but exceedingly bizarre quarries, in that the rock [is] meant to come to them.” They are strange attractors, sometimes “ten times as large as the largest pyramid at Giza.”

[Image: Deflection walls protect houses not from terrorist attack or from runaway automobiles, but from geology: rocks spalling off the nearby hills and rolling through the neighborhood; photo by Friends of the Pleistocene]. [Image: Deflection walls protect houses not from terrorist attack or from runaway automobiles, but from geology: rocks spalling off the nearby hills and rolling through the neighborhood; photo by Friends of the Pleistocene].

Easily one of the most fascinating aspects of our field trip was seeing the sheer quantity of concrete deflection walls—aka Jersey barriers—that have come to line whole streets and front yards in these mountainous neighborhoods.

Objects now more popularly associated with anti-terror measures, these barriers are actually there to protect Los Angeles residents from geology. In many cases, private homes are all but invisible behind monolithic concrete barriers, surely begging a more elegant—not to mention permanent—architectural solution.

Entire, gently curving suburban roadway networks have thus been turned into emergency deflection labyrinths, extending the geometric logic of the debris basins above them.

In any case, I look forward to the results of Friends of the Pleistocene's research, and their post is worth reading in full.

[Image: A swiftlet nesting house in Thailand; photo by Alexander S. Heitkamp, courtesy of Wikipedia]. [Image: A swiftlet nesting house in Thailand; photo by Alexander S. Heitkamp, courtesy of Wikipedia].

"This drab, windowless concrete facade does not conceal an electricity substation, data servers, or a high security detention center," Nicola Twilley writes over at GOOD. It is, instead, a living birds' nest factory, an emerging building type that has "spread across Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam, and even Cambodia, towering above traditional one-story structures and transforming the urban landscape." Their purpose? To foster the production of swiftlet nests, used in Chinese bird's nest soup.

Nicola explains that these nest farms are, in effect, surrogate geological formations: "the buildings are intended to mimic caves," she writes, where the swiftlets would normally live, "with a carefully spaced matrix of wooden rafters replacing the ledges and crannies of a cave ceiling, and detailed attention paid to internal temperature, humidity, and even sound."

They are, in effect, part of what could be called a saliva industry, as the nests are made from swiftlet saliva. A spitshop, say, instead of a sweatshop. Mechanize this one step further, and full-scale 3D saliva-printing might not be far off...

[Image: The spidery and self-supporting Cavity Mechanism #4 w/ Glass Dome by Dan Grayber, courtesy of Johansson Projects]. [Image: The spidery and self-supporting Cavity Mechanism #4 w/ Glass Dome by Dan Grayber, courtesy of Johansson Projects].

Artist Dan Grayber has a new show on display in Oakland, at Johansson Projects. It features an ingenious collection of spring-loaded devices that play on ideas of architecture, tension, mechanics, and space.

[Image: Cavity Mechanism #2 w/ Glass Dome by Dan Grayber, courtesy of Johansson Projects]. [Image: Cavity Mechanism #2 w/ Glass Dome by Dan Grayber, courtesy of Johansson Projects].

They are more like booby traps—their only spatial purpose to support themselves in states of high tension—or re-tuned Vitruvian readymades sealed in glass.

[Image: Cavity Mechanism #6 w/ Glass Dome by Dan Grayber, courtesy of Johansson Projects]. [Image: Cavity Mechanism #6 w/ Glass Dome by Dan Grayber, courtesy of Johansson Projects].

Grayber's Cavity Mechanism #6 w/ Glass Dome, for instance, "is a pair of spring loaded mechanisms that wedge themselves into the inside of a cavity (the glass dome in this case), suspending themselves. Cable running between pair maintains tension on both mechanisms. If cable were to fail, both mechanisms would fall."

[Images: (top) Cavity Mechanism #5 w/ Glass Dome; (middle and bottom) Cavity Mechanism #3 w/ Glass Dome; all by Dan Grayber, courtesy of Johansson Projects]. [Images: (top) Cavity Mechanism #5 w/ Glass Dome; (middle and bottom) Cavity Mechanism #3 w/ Glass Dome; all by Dan Grayber, courtesy of Johansson Projects].

As the gallery describes his work, "Dan Grayber isolates machinery from its usual role of fulfilling human needs through placing it in an eternal mode of self-perpetuation. His safety-orange powder coated objects endlessly assure their survival through completing the simple and essential task of holding oneself up. These sculptures, which create problems as they solve them, exude a sovereign elegance, the dignity of not having to justify themselves to an outside source."

[Image: Untitled (fishbowl) Mechanism by Dan Grayber, courtesy of the artist]. [Image: Untitled (fishbowl) Mechanism by Dan Grayber, courtesy of the artist].

This notion of a "sovereignty" of the object is a compelling one: the aloof, isolated, self-supporting nature of these pieces is done away with utterly the instant they are pulled from their glass domes.

Forced out of what could be called the tautology of the dome—a precise space of limitations in which each mechanism can perform itself endlessly—these arachnid-like devices become functionally useless.

They become not sovereign at all, but parasites robbed of their original, enabling context.

[Image: Column Mechanism #1 by Dan Grayber, courtesy of Johansson Projects]. [Image: Column Mechanism #1 by Dan Grayber, courtesy of Johansson Projects].

An example of Grayber's experiments with this latter spatial condition is Column Mechanism #1.

Removed from the glass vitrine and installed directly on a concrete wall, it "consists of central tensioning mechanisms and eight 'satellite' contact objects, in pairs. Tension created from central mechanism is run through pulleys on each pair of 'satellite' objects, pulling them together, creating tension that squeezes column and supports central piece."

Similarly, the "centrally located springs" of Drywall Mechanism #2 "use bicycle brake lines to carry tension of springs to the outer mechanisms. Outer mechanisms have points that when tensioned simultaneously gently dig into wall surface."

[Images: Drywall Mechanism #2 by Dan Grayber, courtesy of the artist]. [Images: Drywall Mechanism #2 by Dan Grayber, courtesy of the artist].

These latter examples also raise the intriguing possibility of a Dan Grayber installation disguised as everyday construction or architectural testing equipment: devices attached to drywall and concrete, like something straight out of a box from Home Depot. Until you notice the intricate systems of bike cables and tension lines, and the strangely functionless beauty of the forms poised just slightly on the right side of snapping...

[Image: Cavity Mechanism #1 w/ Glass Dome by Dan Grayber, courtesy of the artist]. [Image: Cavity Mechanism #1 w/ Glass Dome by Dan Grayber, courtesy of the artist].

The gallery will be hosting an opening reception on February 4, in case you're in Oakland and want to stop by; tell them you read about it on BLDGBLOG.

With just a few more hours left in GOOD's weeklong festival of food-writing, I thought I'd throw one more post out there: two projects by Lik San Chan.

[Image: From the Madeira Odorless Fish Market by Lik San Chan]. [Image: From the Madeira Odorless Fish Market by Lik San Chan].

The first is the Madeira Odorless Fish Market, from 2006.

Camara de Lobos, Madeira, Chan explains, "is a fishing village located 10km west of the capital, Funchal. The fishing community is quickly dwindling into poverty as Funchal provides its own facilities for fish vending businesses. Camara de Lobos remains the only place in the world where the Black Scabbard fish industry can be self sustained, yet the fishermen still receive second hand pay for their catch as most of it is sold in Funchal."

[Image: Two more sections from the Madeira Odorless Fish Market by Lik San Chan]. [Image: Two more sections from the Madeira Odorless Fish Market by Lik San Chan].

Accordingly, the Odorless Fish Market "provides a place where their catch can be sold directly. The programme consists of a fish market, smokery, fish cookery school cum restaurant run by the fishermen community. Its architecture is technically driven to control Smell, Ventilation and Cooling, to provide a building with a greatly reduced smell of fish. The heart of the architecture is a solar chimney system which uses the consistent madeiran sun to, ironically, ventilate/cool the building."

It is a spatially self-deodorizing architecture of thermal air control.

The second of Chan's projects that I want to look at quickly here is the so-called Tempelhof Ministry of Food, from 2010.

[Image: From the Tempelhof Ministry of Food by Lik San Chan]. [Image: From the Tempelhof Ministry of Food by Lik San Chan].

"Tempelhof Ministry of Food is a bread and fish production community situated on the old airfield of Tempelhof Airport," Chan writes.

More specifically, "the proposal is a joint venture between Edeka and the Berlin State, seeking to help Berlin's current problems of unemployment and social disparity." Local residents can produce their own food, cultivating "a spirit of co-existence and community, which they bring back to other Berliners."

[Image: From the Tempelhof Ministry of Food by Lik San Chan]. [Image: From the Tempelhof Ministry of Food by Lik San Chan].

Of course, it takes more than simply activating a vegetation layer in Photoshop to create a realistic urban food infrastructure, but the technical realization of the images—as well as the historic context of the Berlin Airlift, when Tempelhof effectively became an emergency food-distribution center—make it interesting enough for a quick look.

[Images: From the Tempelhof Ministry of Food by Lik San Chan]. [Images: From the Tempelhof Ministry of Food by Lik San Chan].

Indeed, as much as I like the narrative background for the Tempelhof project, it's simply too hard to tell if there is more to the proposal's otherwise impressive imagery to suggest a financially realistic and socially sustainable intervention into Berlin's existing systems of urban food production.

[Image: From the Tempelhof Ministry of Food by Lik San Chan]. [Image: From the Tempelhof Ministry of Food by Lik San Chan].

Put another way, it's one thing to create, analyze, or even editorially promote architectural projects as narrative ideas—that is, as scenario plans for future landscapes—but it's another thing to look at whether or not such proposals do, in fact, operate successfully as solutions to the problems they highlight.

In any case, the spatial and atmospheric implications of food are foregrounded by both projects, though it is the deliberately complicated, Rube Goldberg-like sectional ventilation chambers seen in the Odorless Fish Market that seem most worthy of further exploration.

—Spaces of Food #5: Madeira Odorless Fish Market and the Tempelhof Ministry of Food

—Spaces of Food #4: Betel Nut Beauties

—Spaces of Food #3: The Mushroom Tunnel of Mittagong

—Spaces of Food #2: Inflatable Greenhouses on the Moon

—Spaces of Food #1: Agriculture On-The-Go and the Reformatting of the Planet

Greenpeace has released these images of a train carrying nuclear waste through Valognes, France. Shot with infrared film, the photos show a demonic red glow coming from inside the bellies of the railcars.

[Images: Via National Geographic]. [Images: Via National Geographic].

"The train is hauling a so-called CASTOR convoy," National Geographic explains, "named after the type of container carried: Cask for Storage and Transport Of Radioactive material. These trademarked casks have been used since 1995 to transport nuclear waste from German power plants to France for reprocessing, then back to Germany for storage."

I'm reminded of a short video shown last week at the Landscape Futures Super-Workshop here in Los Angeles.

Produced by Smudge Studio/ Friends of the Pleistocene, the film shows us a flatbed truck carrying transuranic nuclear waste along a desert highway. As Smudge write, "Our brief passing of this truck was a momentary point of contact with this waste, bound for deep time." Filmed in sepia-toned Super-8, the 35-second film has a timeless and dramatic surreality, verging on postapocalyptic.

I should add, briefly, that the name of the train seen in the first three images—a CASTOR convoy—lends all of this a nicely symbolic overtone. In Roman mythology, Castor and Pollux were twin brothers; Castor was mortal, Pollux immortal, and it should come as no surprise to learn that Castor is eventually killed.

However, in one version of the story, "Castor's spirit went to Hades [Hell], the place of the dead, because he was a human. Pollux, who was a god, was so devastated at being separated from his brother that he offered to share his immortality with Castor or to give it up so that he could join his brother in Hades." I mention this otherwise superficial overlap because Smudge's notion that nuclear waste is on its way to being entombed in "deep time," far below ground, takes on explicitly Hadean resonance when put into the context of something called a CASTOR train.

(Related on BLDGBLOG: One Million Years of Isolation: An Interview with Abraham Van Luik and Fossil Reactors).

[Image: From Betel Nut Beauties by Magda Biernat, courtesy of Clic Gallery]. [Image: From Betel Nut Beauties by Magda Biernat, courtesy of Clic Gallery].

This rounds out today's short series of posts written for GOOD's online festival of food-related writing.

I first heard of the Taiwanese spatial subculture of betel nut shacks last autumn when a former student of mine at USC, Yu-Quan Chen, showed me a project he once proposed, inspired by these anomalous yet everyday spaces.

[Image: From Betel Nut Beauties by Magda Biernat, courtesy of Clic Gallery]. [Image: From Betel Nut Beauties by Magda Biernat, courtesy of Clic Gallery].

I was thus interested to see that Polish-born, New York-based photographer Magda Biernat will be exhibiting a group of images she's made called Betel Nut Beauties, a few examples of which are seen here.

[Image: From Betel Nut Beauties by Magda Biernat, courtesy of Clic Gallery]. [Image: From Betel Nut Beauties by Magda Biernat, courtesy of Clic Gallery].

The Clic Gallery describes Biernat's project as "a photoseries documenting the compelling phenomenon of roadside betel nut stands across Taiwan." A fixture on the streets of urban and suburban Taiwan, these brightly lit, often ramshackle huts sell a mild stimulant made from the nut of the areca palm and wrapped in betel leaves... Staffed almost exclusively by young women, the stands cater to longhaul truck drivers and, like taxi dancers or cigarette girls in casinos, the betel nut girls are encouraged to dress in skimpy clothes to lure in male customers. Snapped while waiting for their next sale, Biernat's compassionate photographs capture the isolation and tedium of these sellers who themselves are on display, a daily existence bounded by walls of glass. Biernat describes these buildings as "luminescent structures" where sex, economics, and food overlap—thus making the title of this post ("spaces of food...") referentially problematic, as if the women themselves are objects of both bodily and aesthetic consumption. "The colorful shops," Biernat writes, "with their scantily clad employees make for a startling contrast against Taiwan's often drab urban landscape."

[Images: From Betel Nut Beauties by Magda Biernat, courtesy of Clic Gallery]. [Images: From Betel Nut Beauties by Magda Biernat, courtesy of Clic Gallery].

"These are glass and neon jewels," Biernat adds, "beckoning the customer with the high of not only the betel nut, but of the interaction with the betel nut girls."

[Images: From Betel Nut Beauties by Magda Biernat, courtesy of Clic Gallery]. [Images: From Betel Nut Beauties by Magda Biernat, courtesy of Clic Gallery].

The exhibition opens February 7 at the Clic Gallery in New York, with an opening reception on February 10.

—Spaces of Food #5: Madeira Odorless Fish Market and the Tempelhof Ministry of Food

—Spaces of Food #4: Betel Nut Beauties

—Spaces of Food #3: The Mushroom Tunnel of Mittagong

—Spaces of Food #2: Inflatable Greenhouses on the Moon

—Spaces of Food #1: Agriculture On-The-Go and the Reformatting of the Planet

It seems appropriate, in the context of GOOD's ongoing week of interdisciplinary food writing, to revisit an old favorite post of mine, written by Nicola Twilley, about the extraordinary mushroom tunnel of Mittagong, where disused industrial infrastructure and an emerging food-production system fortuitously intersect.

[Image: The mushroom tunnel of Mittagong; photo by Nicola Twilley]. [Image: The mushroom tunnel of Mittagong; photo by Nicola Twilley].

To make a long story short, Nicola and I had the pleasure, back in 2009, of visiting an abandoned railway tunnel in the hills southwest of Sydney, Australia, a site that has since been turned into a commercial mushroom farm. Featuring no less than a linear kilometer of underground mycological cultivation—racks upon racks upon racks, fruiting with mushrooms in the semi-darkness—it extended as far as the eye could see.

So, to see what we saw, you really should check out Nicola's post.

—Spaces of Food #5: Madeira Odorless Fish Market and the Tempelhof Ministry of Food

—Spaces of Food #4: Betel Nut Beauties

—Spaces of Food #3: The Mushroom Tunnel of Mittagong

—Spaces of Food #2: Inflatable Greenhouses on the Moon

—Spaces of Food #1: Agriculture On-The-Go and the Reformatting of the Planet

|

|

[Image: 020 by Gerco de Ruijter, 28" x 28", from Baumschule (2008-2010), courtesy of the artist].

[Image: 020 by Gerco de Ruijter, 28" x 28", from Baumschule (2008-2010), courtesy of the artist]. [Image: 010 by Gerco de Ruijter, 28" x 28", from Baumschule (2008-2010), courtesy of the artist].

[Image: 010 by Gerco de Ruijter, 28" x 28", from Baumschule (2008-2010), courtesy of the artist]. [Image: 014 by Gerco de Ruijter, 28" x 28", from Baumschule (2008-2010), courtesy of the artist].

[Image: 014 by Gerco de Ruijter, 28" x 28", from Baumschule (2008-2010), courtesy of the artist]. [Image: 005 by Gerco de Ruijter, 28" x 28", from Baumschule (2008-2010), courtesy of the artist].

[Image: 005 by Gerco de Ruijter, 28" x 28", from Baumschule (2008-2010), courtesy of the artist]. [Image: 009 by Gerco de Ruijter, 28" x 28", from Baumschule (2008-2010), courtesy of the artist].

[Image: 009 by Gerco de Ruijter, 28" x 28", from Baumschule (2008-2010), courtesy of the artist].

[Images: 007 and 032, all by Gerco de Ruijter, 28" x 28", from Baumschule (2008-2010), courtesy of the artist].

[Images: 007 and 032, all by Gerco de Ruijter, 28" x 28", from Baumschule (2008-2010), courtesy of the artist]. [Image: 002 by Gerco de Ruijter, 28" x 28", from Baumschule (2008-2010), courtesy of the artist].

[Image: 002 by Gerco de Ruijter, 28" x 28", from Baumschule (2008-2010), courtesy of the artist]. [Image: 001 by Gerco de Ruijter, 28" x 28", from Baumschule (2008-2010), courtesy of the artist].

[Image: 001 by Gerco de Ruijter, 28" x 28", from Baumschule (2008-2010), courtesy of the artist]. [Image: 028 by Gerco de Ruijter, 28" x 28", from Baumschule (2008-2010), courtesy of the artist].

[Image: 028 by Gerco de Ruijter, 28" x 28", from Baumschule (2008-2010), courtesy of the artist]. [Image: 008 by Gerco de Ruijter, 28" x 28", from Baumschule (2008-2010), courtesy of the artist, a great example of how the "fore and background may slide into each other," as the photographer describes it].

[Image: 008 by Gerco de Ruijter, 28" x 28", from Baumschule (2008-2010), courtesy of the artist, a great example of how the "fore and background may slide into each other," as the photographer describes it].

[Image: Courtesy of

[Image: Courtesy of  [Image: For a project at the Bartlett School of Architecture's

[Image: For a project at the Bartlett School of Architecture's  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: The debris dam & basin at the strikingly beautiful

[Image: The debris dam & basin at the strikingly beautiful  [Image: Deflection walls protect houses not from terrorist attack or from runaway automobiles, but from geology: rocks spalling off the nearby hills and rolling through the neighborhood; photo by

[Image: Deflection walls protect houses not from terrorist attack or from runaway automobiles, but from geology: rocks spalling off the nearby hills and rolling through the neighborhood; photo by  [Image: A swiftlet nesting house in Thailand; photo by Alexander S. Heitkamp, courtesy of

[Image: A swiftlet nesting house in Thailand; photo by Alexander S. Heitkamp, courtesy of  [Image: The spidery and self-supporting

[Image: The spidery and self-supporting  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:

[Images: (top)

[Images: (top)  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:

[Images:

[Images:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: From the

[Image: From the

[Image: Two more sections from the

[Image: Two more sections from the  [Image: From the

[Image: From the  [Image: From the

[Image: From the

[Images: From the

[Images: From the  [Image: From the

[Image: From the

[Images: Via

[Images: Via  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: The

[Image: The