The eclipse is a lion with its tail around the sun

"In a journey that has stretched from the coastline of Namibia to the steamy jungles of Ghana, across crocodile infested lakes and the deserts of Northern Kenya, the cliff-side dwellings of the Dogon in Mali and onto the mysterious archaeological sites of the Egyptian Sahara," a new lecture, hosted by London's Royal Society, "explores Africa's ancient astronomical history."

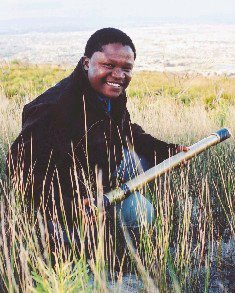

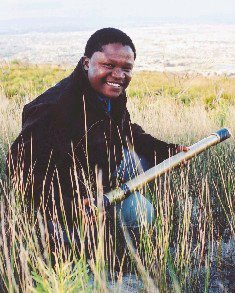

The lecture is given by South African astronomer Thebe Medupe, whose constant grin is only one reason to check out his talk. This bloke is psyched.

Medupe introduces us to "celestial beliefs from different parts of the African continent and how some of these ancient African perceptions link with current scientific knowledge." Part of his expertise is in the "theoretical understanding of stellar oscillations in the atmospheres of stars." He has worked with the so-called Southern African Large Telescope (SALT), hoping "to turn South Africa into a serious scientific power capable of hosting astronomy's greatest prize, a vastly expensive project known as the Square Kilometre Array (SKA)." He's even got a Wikipedia entry.

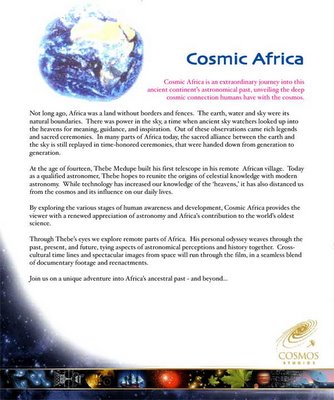

In any case, Cosmic Africa is the name of a 72-minute film, produced by and starring Medupe. (Reviewed here by Variety).

South Africa's official tourism page hypes the film: "Africans told stories about the sky, and saw giraffes, lions and zebras among the stars as naturally as people elsewhere saw bears and horses... To sample the richness of African traditions and achievements, Medupe and the filmmakers travelled around South Africa and to Mali, Egypt and Namibia, learning from local people and sharing modern perspectives."

So now that I've given the film all this free advertising, why is it even interesting?

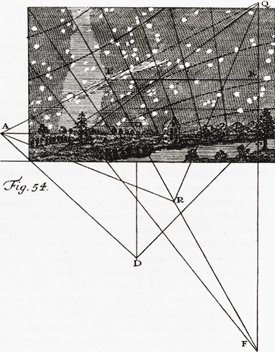

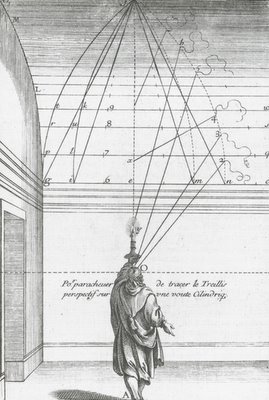

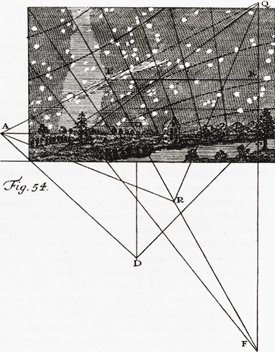

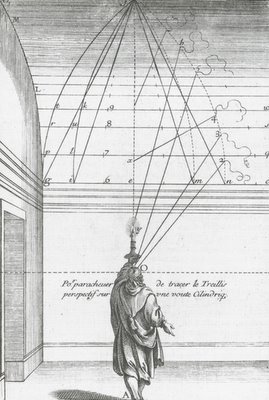

7000-year old ruined observatories and desert megaliths – a so-called "Stonehenge of the Sahara" – have been casting shadows on themselves, marking the solstices, keeping time on abandoned calendars, entangling landscape design with astronomy. The "apparent patterns" in the sky Medupe talks about become architectural diagrams, inverted: the negative space between stars becomes walls, the stars themselves windows, pillars or standing stones. Human movement following a specific astral route, copying migrations of astrochemical fires burning in the vacuum above.

Medupe talks about incidental jottings found in ancient astronomical books, Arabic vs. local languages, a competing marginalia of myth and science, the two fusing to predict next year's eclipse. "I think this is very exciting," he says, and then grins, looking down at his notes.

Orion's belt is actually Three Zebras; Aldebaran is a hunter afraid to return to his wives – who are the Pleiades, the Seven Sisters, with a neighborhood in London named after them. Geography meets geography.

But it's the constellations that fascinate me, the fact that no one today invents their own, or even talks about the stars – assuming they can see them – because the skies have already been named, claimed, put in textbooks.

I once read that the Maya had "dark constellations," areas in the Milky Way with no light, absent geometries of the void; these were actually foxes and llamas. Similar star lore has inspired at least one self-styled historian to propose Polynesian roots for Andean astronomy, ancient mariners canoeing across the seas, those stars memorized or carved as diagrams into boats and oars.

Should there be a kind of import tax on constellations?

But what about 200 years from now, after bird flu and global flooding, after the UK is a new Siberia – or a neo-tropical lagoon – will kids wander north across the Franco-English ice bridge, looking up to locate another London, made of stars – formerly the Pleiades – a walled city of light installed there in the skies of a coming ice age? Or perhaps the Tottenham Court Road, a celestial Thames, Buckingham Palace and Wembley, new mansions of constellated locations in the night? Celestial doubles of our contemporary landscape.

Times Square, rising every autumn; you harvest rhubarb by it. Alexanderplatz. Lake Shore Drive. Mt. Fuji. The Super Mario Cluster. Myths of twins: dragon-slayers.

Perhaps we should renovate the sky.

Architecture has participated with astronomy for so many thousands of years, far longer than its current role as a calculated by-product of cost-benefit charts and insurance liability.

Alignments, symbols, star gardens.

I remember an article in The Guardian, by Kathleen Jamie, who decided to experience astronomy via neolithic architecture left eroding on the Orkney Islands, built to frame the winter solstice: "You are admitted into a solemn place which is not a heart at all, or even a womb, but a cranium. You are standing in a high, dim stone vault. There is a thick soundlessness, as in a recording studio, or a strongroom. A moment ago, you were in the middle of a field, with the wind and curlews calling. That world has been taken away, and the world you have entered is not like a cave, but a place of artifice, of skill. Across five thousand years you can still feel the self-assurance."

In any case, be sure to stop by Medupe's lecture; and then consider renaming your constellations. Maybe post the best ones, in a comment, below.

An Astral I-95. Gemini becomes Bush-Blair. The entire bus route of the 19, from Finsbury Park to Battersea, somehow mapped across a supercluster.

London Eye's wheel of light turning there in space.

The lecture is given by South African astronomer Thebe Medupe, whose constant grin is only one reason to check out his talk. This bloke is psyched.

Medupe introduces us to "celestial beliefs from different parts of the African continent and how some of these ancient African perceptions link with current scientific knowledge." Part of his expertise is in the "theoretical understanding of stellar oscillations in the atmospheres of stars." He has worked with the so-called Southern African Large Telescope (SALT), hoping "to turn South Africa into a serious scientific power capable of hosting astronomy's greatest prize, a vastly expensive project known as the Square Kilometre Array (SKA)." He's even got a Wikipedia entry.

In any case, Cosmic Africa is the name of a 72-minute film, produced by and starring Medupe. (Reviewed here by Variety).

South Africa's official tourism page hypes the film: "Africans told stories about the sky, and saw giraffes, lions and zebras among the stars as naturally as people elsewhere saw bears and horses... To sample the richness of African traditions and achievements, Medupe and the filmmakers travelled around South Africa and to Mali, Egypt and Namibia, learning from local people and sharing modern perspectives."

So now that I've given the film all this free advertising, why is it even interesting?

7000-year old ruined observatories and desert megaliths – a so-called "Stonehenge of the Sahara" – have been casting shadows on themselves, marking the solstices, keeping time on abandoned calendars, entangling landscape design with astronomy. The "apparent patterns" in the sky Medupe talks about become architectural diagrams, inverted: the negative space between stars becomes walls, the stars themselves windows, pillars or standing stones. Human movement following a specific astral route, copying migrations of astrochemical fires burning in the vacuum above.

Medupe talks about incidental jottings found in ancient astronomical books, Arabic vs. local languages, a competing marginalia of myth and science, the two fusing to predict next year's eclipse. "I think this is very exciting," he says, and then grins, looking down at his notes.

Orion's belt is actually Three Zebras; Aldebaran is a hunter afraid to return to his wives – who are the Pleiades, the Seven Sisters, with a neighborhood in London named after them. Geography meets geography.

But it's the constellations that fascinate me, the fact that no one today invents their own, or even talks about the stars – assuming they can see them – because the skies have already been named, claimed, put in textbooks.

I once read that the Maya had "dark constellations," areas in the Milky Way with no light, absent geometries of the void; these were actually foxes and llamas. Similar star lore has inspired at least one self-styled historian to propose Polynesian roots for Andean astronomy, ancient mariners canoeing across the seas, those stars memorized or carved as diagrams into boats and oars.

Should there be a kind of import tax on constellations?

But what about 200 years from now, after bird flu and global flooding, after the UK is a new Siberia – or a neo-tropical lagoon – will kids wander north across the Franco-English ice bridge, looking up to locate another London, made of stars – formerly the Pleiades – a walled city of light installed there in the skies of a coming ice age? Or perhaps the Tottenham Court Road, a celestial Thames, Buckingham Palace and Wembley, new mansions of constellated locations in the night? Celestial doubles of our contemporary landscape.

Times Square, rising every autumn; you harvest rhubarb by it. Alexanderplatz. Lake Shore Drive. Mt. Fuji. The Super Mario Cluster. Myths of twins: dragon-slayers.

Perhaps we should renovate the sky.

Architecture has participated with astronomy for so many thousands of years, far longer than its current role as a calculated by-product of cost-benefit charts and insurance liability.

Alignments, symbols, star gardens.

I remember an article in The Guardian, by Kathleen Jamie, who decided to experience astronomy via neolithic architecture left eroding on the Orkney Islands, built to frame the winter solstice: "You are admitted into a solemn place which is not a heart at all, or even a womb, but a cranium. You are standing in a high, dim stone vault. There is a thick soundlessness, as in a recording studio, or a strongroom. A moment ago, you were in the middle of a field, with the wind and curlews calling. That world has been taken away, and the world you have entered is not like a cave, but a place of artifice, of skill. Across five thousand years you can still feel the self-assurance."

In any case, be sure to stop by Medupe's lecture; and then consider renaming your constellations. Maybe post the best ones, in a comment, below.

An Astral I-95. Gemini becomes Bush-Blair. The entire bus route of the 19, from Finsbury Park to Battersea, somehow mapped across a supercluster.

London Eye's wheel of light turning there in space.

Comments are moderated.

If it's not spam, it will appear here shortly!

Or instead of building a city so its streets align with the stars as they are now - you design everything for 10,000 years in the astronomical future, suddenly Leicester Square perfectly frames Andromeda, and the sun on the solstice rises flawlessly down Oxford Street.

A city calculated in advance to lock into the sky several millennia in the future.

the picture (first one) with the moon is just fantastic

Post a Comment