Autistic Canyons, Icebergs of War, and Architecture Made From Light

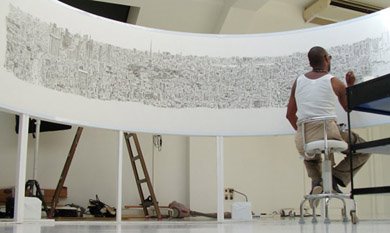

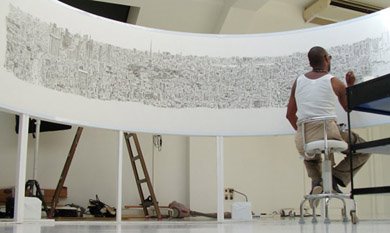

Much has been made over the past ten days of Stephen Wiltshire, an autistic artist based in London. Given an aerial tour of Rome, for instance, Wiltshire soon reproduced the whole city, in astonishing detail, down to the correct number of arches on the Coloseum – drawing the sketch from memory.

Extraordinary though his sketches may be – I like London's Albert Hall, personally, though Wiltshire's oil painting of Los Angeles traffic is also pretty cool – what really got me thinking were the implications this might have for other art forms.

Construction, for instance.

What would happen if you flew a group of autistic miners and bulldozer drivers over the Grand Canyon for several hours? Maybe you even go back the next day, fly circles over certain formations, bank the wings. Memorize fault geometry, strike and dip, the Vishnu schist. Your passengers stare out the window and think. They don't touch their peanuts. They wear seatbelts.

The whole Grand Canyon, up every tributary and side-fractal'd edge, eroded half-canyons of loose pebbles tumbling under footsteps; fissures, gaps.

You then unleash everyone on the plains of central Asia with a fleet of picks and bulldozers: could they exactly reproduce the Grand Canyon? I think they could. I think Stephen Wiltshire could. Give him a jackhammer and come back in two years.

Such questions have been posed on BLDGBLOG before, of course, but couldn't that negative earthwork, that unzipped void, be copied exactly to scale? How long would it take? How precise would it be?

Milling new autistic canyons into the surface of the planet.

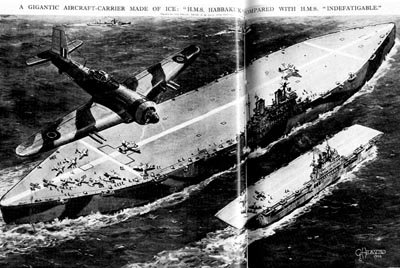

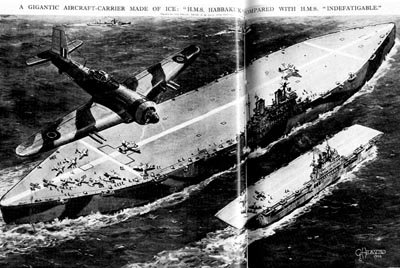

Meanwhile, the Kircher Society, who introduced us to Stephen Wiltshire, also informed us this week that a "massive floating island 2,000 feet long, 300 feet wide, and 40 feet thick" was almost built by the British military during WWII. Called Pykrete, the material it would have been made from was an "almost indestructible mixture of ice and wood pulp" – though it's elsewhere been described as "a compound [made] out of paper pulp and sea water which was almost as strong as concrete" (not quite indestructible, then).

Either way, Pykcrete (also spelled "Pykecrete") would have been used in all manner of ocean-borne construction projects, including a ship that "would serve as a sort of glacial aircraft carrier" in times of war.

Pykcrete structures could not only float, they could repel bullets – an accurate description, on both counts, of my uncle...

Finally, New Scientist gives us the low-down on structures made from light.

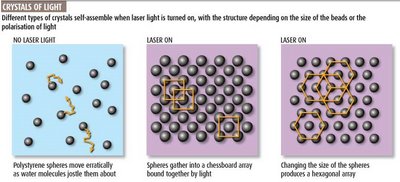

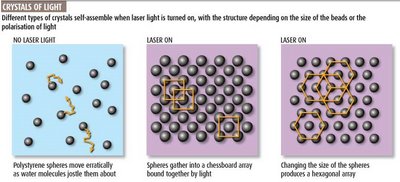

Resembling some kind of Renaissance magic trick, a metal work surface "covered with lenses, prisms and mirrors" can now be used to create solid structures out of light – but only if you've got "polystyrene beads a few hundred nanometres across."

"With a flick of a switch," New Scientist explains, a laser "bathes the beads in an invisible web of infrared light and immediately the beads start collecting... First one or two, then perhaps a dozen fall into line. The beads are still jostling, but something much stronger is holding them in place. Other beads cluster around, seemingly reluctant to join the group. But one by one, they take the plunge, somehow forced into the growing array. Eventually the beads form a chessboard array bound together like a crystal."

This experiment was conducted by Colin Bain, a chemist at England's Durham University. He has made what's called "optical matter" – even "optical cement."

Of course, architectural metaphors are never far off: "In this microscopic construction site," we read, "light acts as architect, bricklayer and construction worker, turning building blocks, into temples."

Bain can change the structures he builds simply by changing the polarization of the light; thus, "suddenly the hexagonal array flips into a square one." Wavelength, frequency, structure.

Meanwhile, optical researchers Jean-Marc Fournier and Tomasz Grzegorczyk "have big ambitions for optical matter. They are investigating ways to build a giant mirror made from particles bound together entirely by laser light. Such a mirror could be a boon for future space telescopes." Specifically, they'd use a laser to "trap" particles, which would then "self-organise into a thin reflecting film that takes the shape of a focusing mirror."

This mirror would apparently be "self-healing."

Next up: skyscrapers, emergency tents, hydroelectric dams, whole suburbs – created with a single beam of light...

Several months ago, NPR's Science Friday aired a show called "Stopping Light" – in which the host, Ira Flatow, interviews an Australian physicist. At one point, as if he hasn't been paying attention, Flatow mutters the strangely uncomfortable, Muppet-like phrase: "Mmm... An archive."

Download the MP3 right here.

(Earlier on BLDGBLOG: A cubic meter of fogged space, and – a personal favorite of mine – A Natural History of Mirrors. And thanks, Leah B., for the tip on Pykrete!)

Extraordinary though his sketches may be – I like London's Albert Hall, personally, though Wiltshire's oil painting of Los Angeles traffic is also pretty cool – what really got me thinking were the implications this might have for other art forms.

Construction, for instance.

What would happen if you flew a group of autistic miners and bulldozer drivers over the Grand Canyon for several hours? Maybe you even go back the next day, fly circles over certain formations, bank the wings. Memorize fault geometry, strike and dip, the Vishnu schist. Your passengers stare out the window and think. They don't touch their peanuts. They wear seatbelts.

The whole Grand Canyon, up every tributary and side-fractal'd edge, eroded half-canyons of loose pebbles tumbling under footsteps; fissures, gaps.

You then unleash everyone on the plains of central Asia with a fleet of picks and bulldozers: could they exactly reproduce the Grand Canyon? I think they could. I think Stephen Wiltshire could. Give him a jackhammer and come back in two years.

Such questions have been posed on BLDGBLOG before, of course, but couldn't that negative earthwork, that unzipped void, be copied exactly to scale? How long would it take? How precise would it be?

Milling new autistic canyons into the surface of the planet.

Meanwhile, the Kircher Society, who introduced us to Stephen Wiltshire, also informed us this week that a "massive floating island 2,000 feet long, 300 feet wide, and 40 feet thick" was almost built by the British military during WWII. Called Pykrete, the material it would have been made from was an "almost indestructible mixture of ice and wood pulp" – though it's elsewhere been described as "a compound [made] out of paper pulp and sea water which was almost as strong as concrete" (not quite indestructible, then).

Either way, Pykcrete (also spelled "Pykecrete") would have been used in all manner of ocean-borne construction projects, including a ship that "would serve as a sort of glacial aircraft carrier" in times of war.

Pykcrete structures could not only float, they could repel bullets – an accurate description, on both counts, of my uncle...

Finally, New Scientist gives us the low-down on structures made from light.

Resembling some kind of Renaissance magic trick, a metal work surface "covered with lenses, prisms and mirrors" can now be used to create solid structures out of light – but only if you've got "polystyrene beads a few hundred nanometres across."

"With a flick of a switch," New Scientist explains, a laser "bathes the beads in an invisible web of infrared light and immediately the beads start collecting... First one or two, then perhaps a dozen fall into line. The beads are still jostling, but something much stronger is holding them in place. Other beads cluster around, seemingly reluctant to join the group. But one by one, they take the plunge, somehow forced into the growing array. Eventually the beads form a chessboard array bound together like a crystal."

This experiment was conducted by Colin Bain, a chemist at England's Durham University. He has made what's called "optical matter" – even "optical cement."

Of course, architectural metaphors are never far off: "In this microscopic construction site," we read, "light acts as architect, bricklayer and construction worker, turning building blocks, into temples."

Bain can change the structures he builds simply by changing the polarization of the light; thus, "suddenly the hexagonal array flips into a square one." Wavelength, frequency, structure.

Meanwhile, optical researchers Jean-Marc Fournier and Tomasz Grzegorczyk "have big ambitions for optical matter. They are investigating ways to build a giant mirror made from particles bound together entirely by laser light. Such a mirror could be a boon for future space telescopes." Specifically, they'd use a laser to "trap" particles, which would then "self-organise into a thin reflecting film that takes the shape of a focusing mirror."

This mirror would apparently be "self-healing."

Next up: skyscrapers, emergency tents, hydroelectric dams, whole suburbs – created with a single beam of light...

Several months ago, NPR's Science Friday aired a show called "Stopping Light" – in which the host, Ira Flatow, interviews an Australian physicist. At one point, as if he hasn't been paying attention, Flatow mutters the strangely uncomfortable, Muppet-like phrase: "Mmm... An archive."

Download the MP3 right here.

(Earlier on BLDGBLOG: A cubic meter of fogged space, and – a personal favorite of mine – A Natural History of Mirrors. And thanks, Leah B., for the tip on Pykrete!)

Comments are moderated.

If it's not spam, it will appear here shortly!

Won't generalise to Grand Canyon. It's all about perceiving structure.

See Kolmogorov complexity.

Kolmogorov canyons, perhaps...

If structures be made of light, properly organised, what then of the opposite: light made from buildings? Are buildings destined to be the new mystery of the universe, both practicle and wave, travelling at infinitesimally slow speeds, except in relation to each other? What them of architecture: will it be the craft of dis-organisation, of scattering matter into evanescent patterns? And will there be any need for windows, or illumination?

I like that Wiltshire made a photographic mental image of Wilshire Blvd in L.A.

What happens when the batteries run down, indeed? What happens when clothes are electronic? When nanotechnology has progressed to the point that a necklace or a ring embedded with a transmitter organises and polarises light around us? So that it looks like we are wearing clothes? No more laundry, no more needing one set of clothes for work and another for travel. And when the battery runs down? Diaphonous garments, new modes of strip-tease? It would, of course, mean the end of pockets.

But then someone will develop actual nanofabrics that are self-organising, and pockets will return. Then someone will figure out how to make space shields; pressure and impact resistant fabrics that will replace bulky space-suits. Forcefields will go out of fashion, inflatable space stations will show up in suburban backyards. As you say, houses will appear and disappear at the flick of a switch. Away on holiday? Turn the house off. No worries about burglars, fires, or the mail piling up. Moving? No problem!

Post a Comment