The uttermost reaches of solar influence

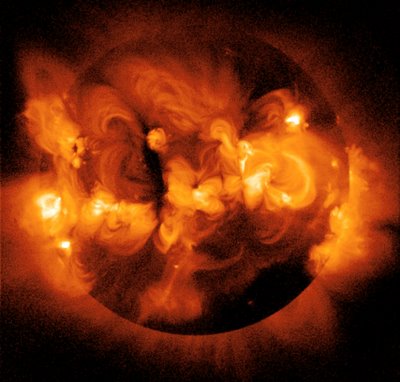

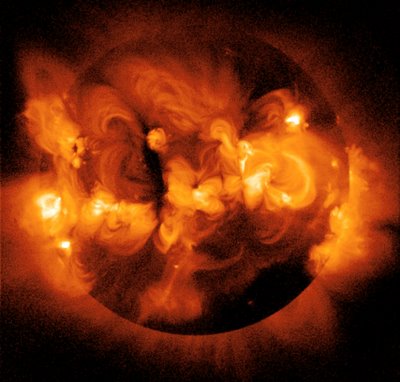

Whilst once again finding myself on the same intellectual wavelength as Pruned's Alex Trevi, who posted today about the shimmering and explosive self-resurfacing outer loops of the sun, I spent yesterday evening copying down solar-descriptive quotations from an old book by Guy Murchie, called The Music of the Spheres.

Now out of print, as well as scientifically outdated, I can still hardly believe how exciting the 2-volume book – about "the material universe, from atom to quasar, simply explained" – is to read, and how interestingly poetic Murchie's take on the subject really is. His chapter 6, for instance, is an "Introduction to the Sun," our local star in which "something much more profound and basic than fire is blazing."

I get light-headed when I read that the surface of the sun "is really a thousand times more vacuous than a candle-flame on Earth, and even the concentrated moiling gases hidden a thousand miles below it are a hundred times thinner than earthly air." Indeed, some stars, such as E Aurigae I – a star so huge that it could "contain most of our solar system, including the 5.5-billion-mile circumference of Saturn's orbit" – "are sometimes described as 'red-hot vacuums' because their material, though hot, averages thousands of times thinner than earthly air and is normally invisible, so that you might fly through them for days in your insulated space ship without even realizing you were inside a star."

Meanwhile, in the sun's whirling interior, "the highly compressed gassy matter is ten times as dense as steel." Then, of course, there are "magnetic hurricanes thousands of miles in diameter" – which would be a lot more exciting if those magnetic hurricanes were not "commonly known on Earth as sunspots."

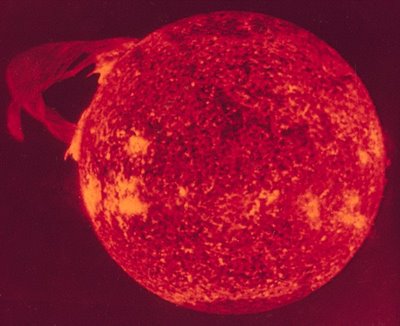

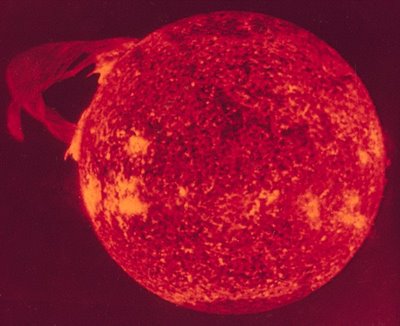

As the sun unceasingly explodes in arching structures of storm and prominence, "glowing veils of gaseous calcium" escape. In others words, the same mineral responsible for animal bones bursts outward from the sun in astrophysical shells that "look like gnarled trees with blazing rain pouring downward from their branches in beautiful magnetic curves that have been clocked at speeds up to 400 miles a second."

The universe is loud with intercelestial thunder; there are "vast magnetic influences" at work across all scales of matter; "ionic 'noise storms' at radio frequencies" scream ceaselessly through antenna'd headsets of home astronomers; there is even a sunspot cycle that "corresponds to a '212-day cycle noted in some studies of human pulse rates'." Incredibly, some "outlying clusters" of stars at the edge of the Milky Way "overlap each other so densely they are literally buried in light."

In any case, I think every child in the world would become a scientist if they read Murchie's 2-volume book – but it's out of print. Alas. Perhaps, instead, we can all just watch this extraordinary short film, wherein sound art meets video art meets solar astronomy.

[Note: All emphases added. Elsewhere: Pruned's Sunscapes (where reader comments tipped us off to the film link, supplied above). Other elsewhere: The Surface of the Sun, a website claiming that the sun is, in fact, solid – furthermore, that it contains something called "solar moss." Earlier on BLDGBLOG: Podcasting the sun].

Now out of print, as well as scientifically outdated, I can still hardly believe how exciting the 2-volume book – about "the material universe, from atom to quasar, simply explained" – is to read, and how interestingly poetic Murchie's take on the subject really is. His chapter 6, for instance, is an "Introduction to the Sun," our local star in which "something much more profound and basic than fire is blazing."

I get light-headed when I read that the surface of the sun "is really a thousand times more vacuous than a candle-flame on Earth, and even the concentrated moiling gases hidden a thousand miles below it are a hundred times thinner than earthly air." Indeed, some stars, such as E Aurigae I – a star so huge that it could "contain most of our solar system, including the 5.5-billion-mile circumference of Saturn's orbit" – "are sometimes described as 'red-hot vacuums' because their material, though hot, averages thousands of times thinner than earthly air and is normally invisible, so that you might fly through them for days in your insulated space ship without even realizing you were inside a star."

Meanwhile, in the sun's whirling interior, "the highly compressed gassy matter is ten times as dense as steel." Then, of course, there are "magnetic hurricanes thousands of miles in diameter" – which would be a lot more exciting if those magnetic hurricanes were not "commonly known on Earth as sunspots."

As the sun unceasingly explodes in arching structures of storm and prominence, "glowing veils of gaseous calcium" escape. In others words, the same mineral responsible for animal bones bursts outward from the sun in astrophysical shells that "look like gnarled trees with blazing rain pouring downward from their branches in beautiful magnetic curves that have been clocked at speeds up to 400 miles a second."

The universe is loud with intercelestial thunder; there are "vast magnetic influences" at work across all scales of matter; "ionic 'noise storms' at radio frequencies" scream ceaselessly through antenna'd headsets of home astronomers; there is even a sunspot cycle that "corresponds to a '212-day cycle noted in some studies of human pulse rates'." Incredibly, some "outlying clusters" of stars at the edge of the Milky Way "overlap each other so densely they are literally buried in light."

In any case, I think every child in the world would become a scientist if they read Murchie's 2-volume book – but it's out of print. Alas. Perhaps, instead, we can all just watch this extraordinary short film, wherein sound art meets video art meets solar astronomy.

[Note: All emphases added. Elsewhere: Pruned's Sunscapes (where reader comments tipped us off to the film link, supplied above). Other elsewhere: The Surface of the Sun, a website claiming that the sun is, in fact, solid – furthermore, that it contains something called "solar moss." Earlier on BLDGBLOG: Podcasting the sun].

Comments are moderated.

If it's not spam, it will appear here shortly!

Just for the record, the title of this post is a phrase written by Guy Murchie; it can be found on page 155, in volume one...

Gorgeous.

'"glowing veils of gaseous calcium" escape. In others words, the same mineral responsible for animal bones bursts outward from the sun in astrophysical shells that "look like gnarled trees with blazing rain pouring downward from their branches in beautiful magnetic curves"'

Pearls are made of calcium, right? Aside from that, this description is as bewildering as it is poetic. I have no idea about the thing he's described.

And what of those regions of red-hot gas? What keeps them hot if they're in a vacuum, and separated to the extent described?

e-tat - He's describing the umbrella-like torrents of gas that arc outward with every solar prominence. And, unless I've misunderstood this, it's the reactivity - the radiation - that keeps those asymptotic non-vacuums glowing hot. Stars that aren't stars...

The space between stars isn't an entirely empty vacuum. Perhaps fifteen percent of the galaxy's mass is tied up in what is called the interstellar medium. Of that, more than ninety-nine percent is gas. The rest is dust--flakes and needles of carbon and silica, formed in the cool upper layers of red giant stars and dispersed by solar winds.

Individual particulates of this dust are roughly the size of the wavelength of blue light. Whenever starlight passes through a cloud of it, its blue wavelengths get scattered. Every wavelength of light passing through the dust will be dimmed somewhat. This effect is called "extinction."

Until recently, astrophysicists believed most interstellar carbon was graphite. There is mounting evidence to suggest microdiamond flakes account for some large part of the extinction, however.

Think of it. The extinction of starlight.

Post a Comment