Altering Antarctica

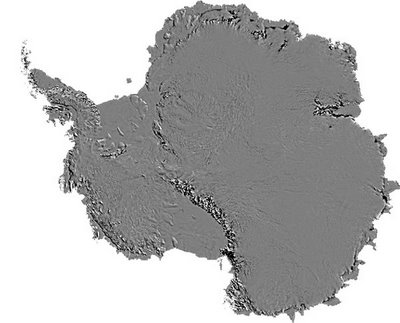

[Image: Courtesy of NASA's Earth Observatory].

There are a wide variety of overlooked and forgotten ways in which humans participate with, and alter, the biological systems around them. A few seeds, trapped in the soles of our shoes, can cross oceans with us in airplanes, bringing gardens, and weeds, and parasite species, to the other side of the earth; trace amounts of infectious diseases can cling to our clothes and decimate livestock several nations away; snakes, rats, spiders, mosquitoes – all can easily ride the ships and planes of globalization.

Our economy is crowded with invasive stowaways intent on surviving elsewhere – even if survival means irretrievably altering the new host environment.

In other words, travel itself can be something of a biological activity: we do the migratory work of other species for them. We take them with us. Importations of even the smallest microbe can sufficiently alter an ecological niche, opening it up to further changes – then compounding over time into whole new landscapes. What would happen naturally is accelerated: a thousand years in a decade.

It shouldn't surprise us, then, to learn that strange things are afoot in Antarctica.

(To read more, you'll have to visit WorldChanging – for whom this post was originally written).

Comments are moderated.

If it's not spam, it will appear here shortly!

But invasion (or exploitation) of its environment is the very nature of life. I doubt if we can ultimately stop it on a microscopic or macroscopic level. As Jeff Goldblum's chaos character said in Jurassic Park (while expressing doubt about attempting to contain the cloned dinosaur population on the island), "Life will find a way."

How many species in a given geographical area are still the originals? Ownership naturally changes over time, and, to mangle a phrase, "Progression may be 9/10ths of natural law." If conditions change so that the original species (or something similar to them) reoccupy their place, is that invasion or repopulation?

Perhaps we — the most invasive species of all — overestimate our influence. Nature does a pretty good job of it, and maybe Antarctica is just trying to revive itself.

cenoxo, I agree that biology inherently spreads and invades and colonizes and inhabits where it can; in this case, though, it's not a question of Antarctica reviving itself - in the active voice - it's Antarctica having seeds and microbes and other species introduced onto it - in the passive voice. It's receiving these things, not instigating them on its own through some complex ecospheric mutation. This may be Antarctica's vivification, in other words, but it's not a reviving, because these species - North American weeds, etc. - were not there before.

But the invasive nature of life itself is clear; even in the invasion biology literature you pick up a kind of nagging self-doubt that the whole field may be something of an illusion. If, as Alan Burdick writes in the book I quote in this post, a finch gets blown off course and lands on an island; then another finch; then reproduction; then survival; then adaptation to the environment and suddenly finches are naturalized - that's still an ecological invasion, albeit one that has apparently less catastrophic side-effects, and unfolds over a slighter greater period of time.

In any case, it's not a question of maintaining the continent, or the whole earth, in some artificially regulated version of itself 3000 years ago, i.e. radically preserving landscapes and the environment; it's more a question of not bringing a pit bull to a kid's 3rd birthday party. In other words, it's about not wiping out a whole island in ten years, and then realizing, my god, if only we'd scrubbed our shoes before we got off the ship... Or whatever scenario fits here.

But life invades itself everywhere, always. Tropical winds change and predatory birds find themselves migrating over new chains of islands - where they quickly destroy the local turtle population (or whatever). Soon other species take the initiative and fill certain ecological holes, and the entire island ecosystem changes radically. Then a human arrives 15 years later and he or she doesn't even see the signs of this catastrophe: it looks like "nature" to us - and it is nature. These invasions are happening everywhere, always, we just don't see them because we don't know what was there before.

Anyway, the question, in terms of Antarctica, is not: How can we prevent the island from ever changing in any way? Nor is it: How are humans responsible for all biological change in the south polar sea? But: To what extent can you still visit and study something without irretrievably altering it in the process? How can this alteration be limited in scope?

My suggestion that Antarctica might be reviving itself was somewhat tongue in cheek. It's more the idea that a highly complex ecosystem is self-repairing, but it doesn't necessarily return to its original state (hence the Krakatau link). You can't step into the same river twice.

There are six billion of us and counting. If we are visitors, clearly we've moved in and brought all our junk along with us. Our effect on the Earth (or anywhere else we may go) is going to continue. Trying to mitigate this may be beneficial—by what definition?—but will only slow it down, not stop it.

If you compare Antarctica's current condition to its fossil record, it's a desert in every sense of the word. If, in the long term, man's presence on the planet terraforms the continent (through global warming) back to a rain forest, would this be an ecological success or a disaster?

Post a Comment