10 Mile Spiral

[Image: 10 Mile Spiral, "A Gateway to Las Vegas," by Benjamin Aranda and Chris Lasch].

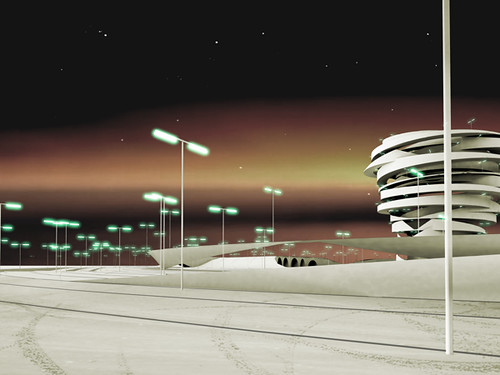

[Image: 10 Mile Spiral, "A Gateway to Las Vegas," by Benjamin Aranda and Chris Lasch].In their recent and immensely enjoyable book Tooling, New York-based architects Benjamin Aranda and Chris Lasch propose, among other things, a "10 mile spiral" that will "serve two civic purposes for Las Vegas":

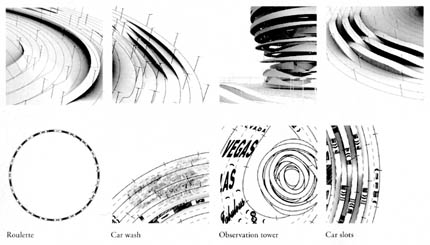

- First, it acts as a massive traffic decongestion device... by adding significant mileage to the highway in the form of a spiral. The second purpose is less infrastructural and more cultural: along the spiral you can play slots, roulette, get married, see a show, have your car washed, and ride through a tunnel of love, all without ever leaving your car. It is a compact Vegas, enjoyed at 55 miles per hour and topped off by a towering observation ramp offering views of the entire valley floor below.

[Image: Aranda/Lasch, from Tooling].

[Image: Aranda/Lasch, from Tooling].Drivers will enter this vertical labyrinth of concrete, approaching a whirligig-like compression of the desert horizon and gradually lifting off into the sky. It's a kind of herniation of space through which you could theoretically drive forever. (Given enough gasoline).

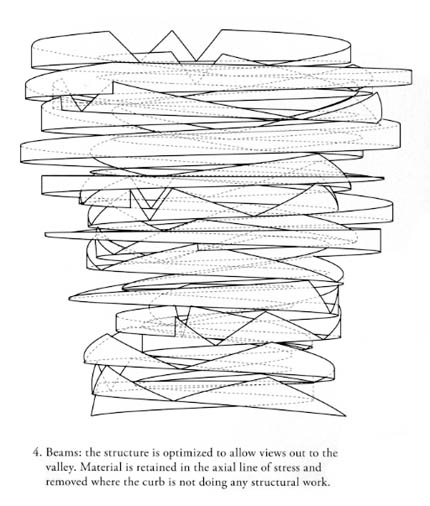

The spiral itself is beautiful –

– and absurd. Its form was generated algorithmically as "a helix whose radius varies randomly as it climbs and then falls back down to the valley floor." The structure's "intersection points" are then located, acting as stress-sites "through which the structure's loads are channeled to the ground."

– and absurd. Its form was generated algorithmically as "a helix whose radius varies randomly as it climbs and then falls back down to the valley floor." The structure's "intersection points" are then located, acting as stress-sites "through which the structure's loads are channeled to the ground." It's an internally buttressed Futuro-Suprematist cathedral to cars.

[Image: Aranda/Lasch, from Tooling].

[Image: Aranda/Lasch, from Tooling].At the end of the book, Aranda/Lasch note that every project featured in Tooling was "constructed through simple steps, repeated over and over until something of substance was revealed":

- These steps are usually straightforward geometric transformations – short sets of rules that we develop – sometimes to build a custom tool that had not yet existed, but more often to better understand the forms we wish to make. Tapping the number-crunching power of the computer opens up new design possibilities and gives us the capacity to grow and proliferate structures that we otherwise could not, but probably more important is deciding when to curb their growth, cut their shape, or stop using them altogether.

At some point, Aranda/Lasch add, all the algorithmic tools they themselves used will be made available to anyone else who wants to explore them; to see if that's happened yet, check this website in a few months' time.

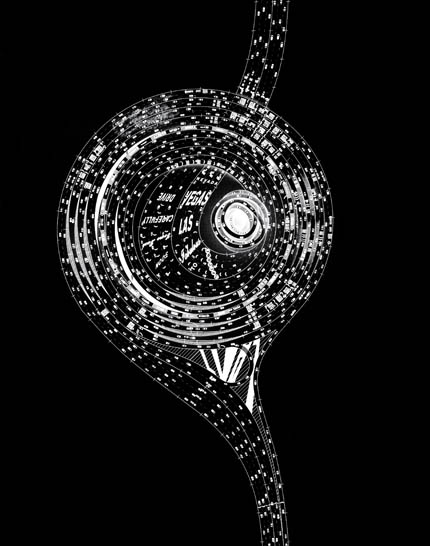

[Image: The spectacular glowing interior of that which has no outside: it's the 10 Mile Spiral from above, at night, lit from within by automobiles. Aranda/Lasch, from Tooling].

[Image: The spectacular glowing interior of that which has no outside: it's the 10 Mile Spiral from above, at night, lit from within by automobiles. Aranda/Lasch, from Tooling].I can't end this post, however, without quoting J.G. Ballard; it's like a nervous tic, seeing so many roads – and out comes Concrete Island, Ballard's now-classic novel about an architect trapped by a car crash in the "compulsory landscaping" of Greater London's excess motorways: "In his aching head the concrete overpass and the system of motorways in which he was marooned had begun to assume an ever more threatening size. The illuminated route indicators rotated above his head, marked with meaningless destinations."

The man falls prey to thirst, insomnia, delirium: "Gazing up at the maze of concrete causeways illuminated in the night air, he realized how much he loathed all these drivers and their vehicles."

The man then searches for "some circuitous route through the labyrinth of motorways" – but finds none. He is trapped, a new Crusoe of roads, "alone in this forgotten world whose furthest shores were defined only by the roar of automobile engines... an alien planet abandoned by its inhabitants, a race of motorway builders who had long since vanished but had bequeathed to him this concrete wilderness."

Leading me to wonder: what new futures of human experience could arise in the 10 Mile Spiral?

[Image: Aranda/Lasch, from Tooling].

[Image: Aranda/Lasch, from Tooling].(For more on Concrete Island, see BLDGBLOG's own Concrete Island, in which those same quotations appear. Then, after you've express-ordered your own copy of Tooling – because any book with a chapter called "Computational Basketry" should be required reading – you can visit Benjamin Aranda's and Chris Lasch's work at the University of Pennsylvania's Non-Linear Systems Organization, where they were recently research Fellows).

Comments are moderated.

If it's not spam, it will appear here shortly!

I'm glad it's all theoretical, because honestly that would suck. More roads? No thanks.

I agree with Anonymous. The "revolutionary" idea of enjoying Las Vegas by highway is, unfortunately, a perfect fit for a school that has tragically become near-irrelevant in thirty short years.

"What new futures of human experience could arise in the 10 Mile Spiral?"

Are you kidding? I mean, really. It's time to realize that Ballard is writing about the present, not some fantastic future.

It's sad that architects are resorting to essentially arbitrary algorithms to generate their ideas.

George Packer wrote in his New Yorker

review of "The Good Fight" that

"Large ideas drawn from historical analogies can help as guiding frameworks, but the glamorous certainties they seem to offer are illusions; we still have to think for ourselves."

Same goes for architects and algorithms.

Thanks for this note, good congestion project

We all know there should be less cars on the road, but that's not the point. I think the spiral is pretty cool as a project, I actually like the idea of a bit of natural randomness in design.

Of course, I'm not kidding; I think this idea is hilarious, absurd, ridiculous, beautifully rendered, ironic, strangely appropriate to the context, and great. Do I want to see it built? Of course not. But I also missed the spot where Ballard's citations from Concrete Island say how fantastic the automobile-clogged urban world is; it sounds rather the opposite to me. Thus, irony.

"New futures of human experience" might mean serial murder and social breakdown, inside some 10-mile tarmac'd spiral in the desert. Which, again, strikes me as absolutely hilarious - and another good reason why this thing is not being built. Not to mention air pollution.

Also, arbitrary algorithms may seem like a mathematically anticlimactic next chapter in the history of architecture, but designing structures based on constraints - from the Doric order to urban zoning restrictions - has been shaping architecture from the outside-in all along. So using algorithms is only as arbitrary as using the Gothic order, or Palladianism - and yet it is simultaneously much less arbitrary than, say, Daniel Libeskind's self-expressive use of non-algorithmic twists, cuts, and reversals. So the arbitrary argument doesn't strike me as particularly valid here, expecially as "thinking for oneself" seems almost hubristic in light of architecture's constant, and invigorating, dependence on outside influences, whether that's a changing budget or the availability of materials or the site's uncomfortable dimensions. It's the outside that gives architecture shape.

Anyway, I knew this project would annoy people, but I think it's funny. If someone wanted to build a floating mega-McDonald's in the middle of the Arctic Ocean I'd be horrified - but I'd still post about it, and I'd think it was funny.

Dave - Thanks for the New Yorker link, meanwhile, which I actually clipped out of a print copy of the magazine a few weeks ago. It's sitting on the kitchen table even as I type this... Good article.

I'd have to agree that the "idea is hilarious, absurd, ridiculous, beautifully rendered, ironic, strangely appropriate to the context."

Great? Mmmm.

When I used the word "fantastic" in reference to Ballard, I meant in the sense of imaginary, not in the sense of "awesomely cool." Of course, Ballard's work would be useless with recognizing the irony involved.

The problem I have is using the term "new futures of human experience" to mean "serial murder and social breakdown." These experiences are hardly new or futuristic. Now, the obvious counter is that we can't specify what the new experiences would be, since we haven't built the spiral.

BUT I would say that the spiral is pretty similar to a bunch of things that have actually been built. The Baltimore "knot" interchange is a good example.

I guess I am venting a bit. Since the highway system was begun, its detrimental effect on the psyche has been widely acknowledged. I just don't think imagining a sort of huge highway/arcology is any stretch of the imagination, really. You are right, though: nice renderings.

AS to the arbitrary/algorithm issue: There is a world of difference between the Doric order and a algorithmically extrapulated building form. The Doric order, whatever its origins, has a specific signification in the Western tradition. (Eastern, too. Just not as positive!) The Doric order isn't a constraint so much as a shortcut. Now, I don't advocate classical architecture. But I do advocate humanist architecture.

I agree that outside influences are essential to architecure, which is exactly why the algorithm is bad. The algorithm denies any outside influences

I think your mention of the Gothic style is a good one. Gothic architecture, unlike the Classical orders, had little in terms of formal language, but more of an organic connection of one structual piece to another. But there is a difference between using a system to create a form that you want and merely devising a formula that self-propogates. Like it or not, figuring out what is desirable or not is the primary job of architects.

Anyway, my thanks for highlighting this project and the many others on the blog. It's fun.

P.S. god forbid an architect should be "hubristic!"

A holding pattern for cars on the move is more urgently needed in higher density cities like LA, where no one might even notice that they've entered an automotive death spiral.

It also promises all kinds of drive-through retail opportunities: a spiral mall, if you please. For instance, drop off your drycleaning at a "core store" on the incoming ramp, and pick it back up your way out. Or, if you get tired of glimpsing all the beautiful natural scenery (around Las Vegas?), you could always watch sequential billboards — or, this being Sin City, a NquiteSFW movie — go by like a gigantic helical zoetrope.

This reminds me of the scene in the excellent French film Microcosmos (scroll down for images) where a convoy of bumper-to-bumper caterpillars end up following each other around in a circle.

As a former Vegas resident, the problem with this project is that it is contrary to the very nature of modern Las Vegas.

This is a customer trap, one that keeps people and money on the road and far away from slot machines, restaurants and shows. The last thing the folks coming from LA want at the end of their long trip would be add a 20 minute drive with the casino's so close at hand.

More importantly, only a small percentage of visitors come to the city in cars.

Quick note: Dave, check out the knot driver... More freeway speculations.

i wanna hit that thing on my longboard soo badly

Ironic or not I think this is also "great". Me likes.

can't find a link to give but this puts me in mind of the story the southern thruway by julio cortazar, where a traffic jam extends from hours to days to years, a whole self-caring civilization, that then dissipates as the cars begin moving again.

cenoxo:

the caterpillar chain in microcosmos is probably inspired by J Henri Fabre who coaxed a train of pine processionary caterpillars onto the rim of a palm-vase which they walked around, one always following another, for seven straight days without food.

But, Vegas being "sin city" the 10 Mile Spiral can be read as a sort of purgatory

where visitors to cast off what happened in Vegas and leave it in Vegas. The fifth terrace is completely congested.

Post a Comment