|

|

"The moon," New Scientist claims, "is about to follow the fate of Antarctica, which remained virtually untouched for nearly half a century after the first intrepid explorers penetrated its vast expanse. What followed was a mushrooming cluster of year-round laboratories, observatories and research facilities used by tens of thousands of scientists in summer and a thousand more who brave the long, dark winter."  [Image: Where to site a lunar laboratory; New Scientist]. Deep within such a permanent lunar base, scientists will find an "interference-free environment," which is "the perfect place to search for signs of extraterrestrial intelligence." Though one is forced to wonder: if the scientists aren't on Earth anymore... won't they themselves constitute a source of extraterrestrial intelligence? In any case, in "certain places near the poles" these scientists will find "perpetual sunlight, handy for continuous solar power; and in the shadows of crater rims, perpetual darkness, ideal for astronomy... Plus, there is a rock-steady surface on which to build structures, and the materials with which to build them." Except – that's not entirely true: in fact, the very real risk of " deep moonquakes," NASA warns, is so great that the astronauts "may need quake-proof housing." Finally, somebody go get Barry White 'cause "there are sites available where the nights are long and uninterrupted" – and that's all I gotta say about that. [See also: Lunar urbanism 5, Lunar urbanism 4 – et cetera].

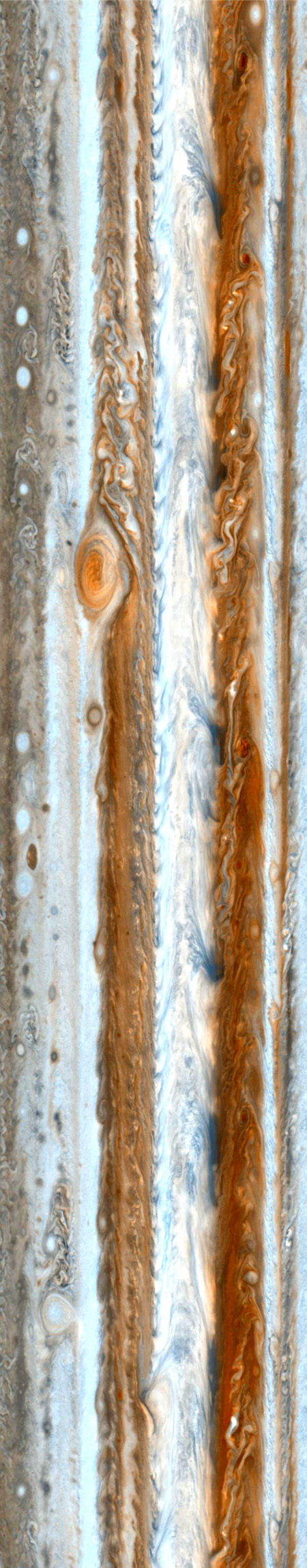

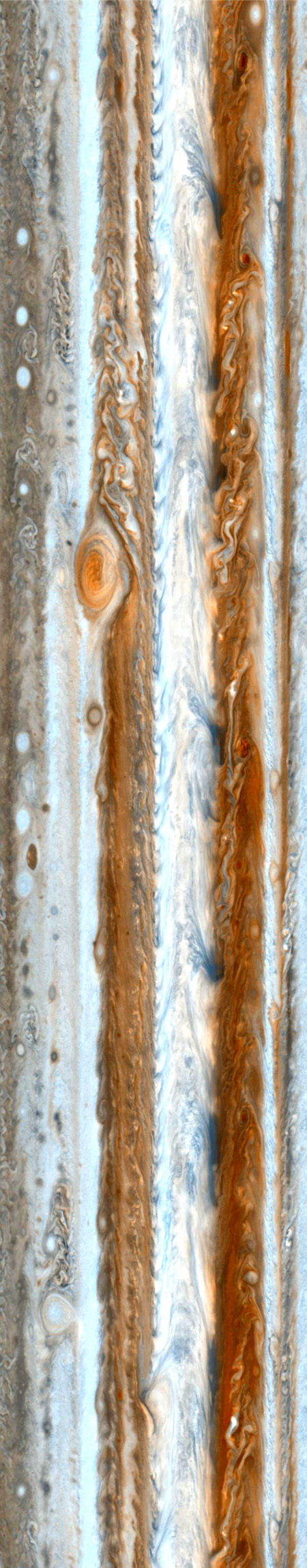

Pruned's resident genius, Alex Trevi, continues to pour shame on the blogosphere, this time by digging up an unbelievable image of Jupiter re-imaged as a cylinder, unrolled as a scroll – complete with what Mr. Trevi calls "dendritic hyper-mississippian superstructures."

Read more, at Pruned.

[Image: Australia's Great Barrier Reef]. [Image: Australia's Great Barrier Reef].

A "vanished giant has reappeared in the rocks of Europe," New Scientist writes. It extends "from southern Spain to eastern Romania, making it one of the largest living structures ever to have existed on Earth."

This "bioengineering marvel" is actually a fossil reef, and it has resurfaced in "a vast area of central and southern Spain, southwest Germany, central Poland, southeastern France, Switzerland and as far as eastern Romania, near the Black Sea. Despite the scale of this buried structure, until recently researchers knew surprisingly little about it. Individual workers had seen only glimpses of reef structures that formed parts of the whole complex. They viewed each area separately rather than putting them together to make one huge structure."

[Image: The reefs of Raiatea and Tahaa in the South Pacific; NASA/LiveScience]. [Image: The reefs of Raiatea and Tahaa in the South Pacific; NASA/LiveScience].

In fact, Marine Matters, an online journal based in the Queen Charlotte Islands, thinks the reef was even larger: "Remnants of the reef can be found from Russia all the way to Spain and Portugal. Portions have even been found in Newfoundland. They were part of a giant reef system, 7,000km long and up to 60 meters thick which was the largest living structure ever created."

[Image: The Pearl and Hermes Atoll, NW Hawaii, via NOAA Ocean Explorer]. [Image: The Pearl and Hermes Atoll, NW Hawaii, via NOAA Ocean Explorer].

The reef's history, according to New Scientist: About 200 million years ago the sea level rose throughout the world. A huge ocean known as the Tethys Seaway expanded to reach almost around the globe at the Equator. Its warm, shallow waters enhanced the deposition of widespread lime muds and sands which made a stable foundation for the sponges and other inhabitants of the reef. The sponge reef began to grow in the Late Jurassic period, between 170 and 150 million years ago, and its several phases were dominated by siliceous sponges. Rigid with glass "created by using silica dissolved in the water," this proto-reef "continued to expand across the seafloor for between 5 and 10 million years until it occupied most of the wide sea shelf that extended over central Europe."

Thus, today, in the foundations of European geography, you see the remains of a huge, living creature that, according to H.P. Lovecraft, is not yet dead.

Wait, what—

"We do not know," New Scientist says, "whether the demise of this fossil sponge reef was caused by an environmental change to shallower waters, or from the competition for growing space with corals. What we do know is that such a structure never appeared again in the history of the Earth." (You can read more here).

For a variety of reasons, meanwhile, this story reminds me of a concert by Japanese sound artist Akio Suzuki that I attended in London back in 2002 at the School of Oriental and African Studies. That night, Suzuki played a variety of instruments, including the amazing "Analapos," which he'd constructed himself, and a number of small stone flutes, or iwabue.

The amazing thing about those flutes was that they were literally just rocks, hollowed out by natural erosion; Suzuki had simply picked them up from the Japanese beach years before. If I remember right, one of them was even from Denmark. He chose the stones based on their natural acoustic properties: he could attain the right resonance, hit the right notes, and so, we might say, their musical playability was really a by-product of geology and landscape design. An accident of erosion—as if rocks everywhere might be hiding musical instruments. Or musical instruments, disguised as rocks.

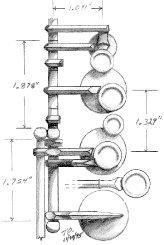

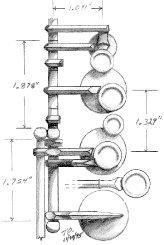

[Image: Saxophone valve diagram by Thomas Ohme]. [Image: Saxophone valve diagram by Thomas Ohme].

But I mention these two things together because the idea that there might be a similar stone flute—albeit one the size and shape of a vast fossilized reef, stretching from Portugal to southern Russia—is an incredible thing to contemplate. In other words, locked into the rocks of Europe is the largest musical instrument ever made: awaiting a million more years of wind and rain, or even war, to carve that reef into a flute, a flute the size of a continent, a buried saxophone made of fossilized glass, pocketed with caves and indentations, reflecting the black light of uncountable eclipses until the earth gives out.

Weird European land animals, evolving fifty eons from now, will notice it first: a strange whistling on the edges of the wind whenever storms blow up from Africa. Mediterranean rains wash more dust and soil to the sea, exposing more reef, and the sounds get louder. The reef looms larger. Its structure like vertebrae, or hollow backbones, frames valleys, rims horizons, carries any and all sounds above silence through the reef's reverberating latticework of small wormholes and caves. Musically equivalent to a hundred thousand flutes per square-mile, embedded into bedrock.

[Image: Sheridan Flute Company]. [Image: Sheridan Flute Company].

Soon the reef generates its own weather, forming storms where there had only been breezes before; it echoes with the sound of itself from one end to the next. It wakes up animals, howling.

For the last two or three breeding groups of humans still around, there's an odd familiarity to some of the reef-flute's sounds, as if every two years a certain storm comes through, playing the reef to the tune of... something they can't quite remember.

[Image: Sheridan Flute Company]. [Image: Sheridan Flute Company].

It's rumored amidst these dying, malnourished tribes that if you whisper a secret into the reef it will echo there forever; that a man can be hundreds of miles away when the secret comes through, passing ridge to ridge on Saharan gales.

And then there's just the reef, half-buried by desert, whispering to itself on windless days—till it erodes into a fine black dust, lost beneath dunes, and its million years of musicalized weather go silent forever.

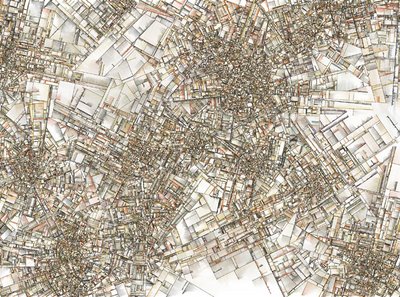

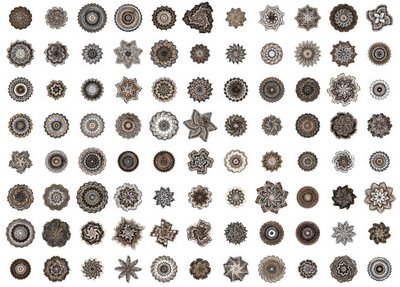

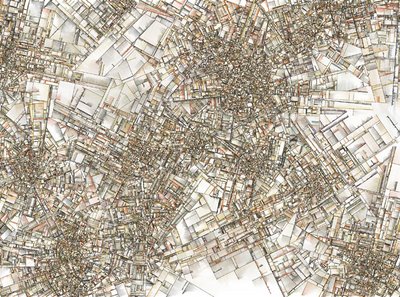

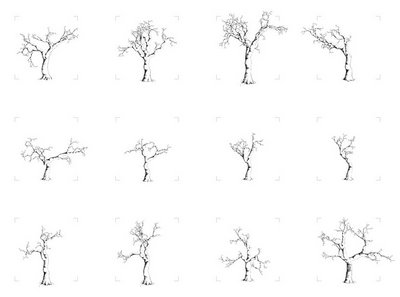

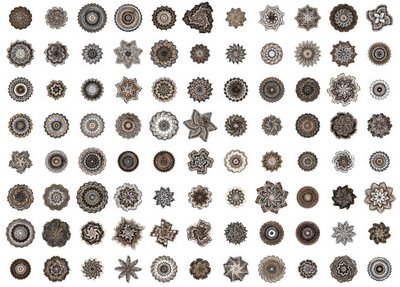

These were all drawn by a computer, using code by Jared Tarbell.  The above image – called Substrate – is only one stage in a long algorithmic process. The various versions morph through different, oddly city-like fractal patterns, forming boulevards, squares, medinas – and reminding me of central Fes. A few intermediary steps:    And some square ones:   All of which leaves me to wonder if the Artificially Intelligent city of the future will constantly reprogram itself, forming new wards and clusters where there had only been streets before – only to back-track, erupting fungus-like in bursts of self-assembled geometry. Weird overlaps and elisions. Symmetrical superslums. Alternatively, you could create a videogame that reprograms itself as it's played – forming new and unique levels, none of which ever repeats itself – and the maps you try to make... look like these. Meanwhile, Tarbell's algorithms also produce more organic forms:   [Note: It's worth clicking on the sand dollars and scrolling down]. So if algorithms ever broke into a genetic lab – what might crawl out the next day? Finally, there's this beautifully tangled, gravitationally avant-garde quasi-planet, like someting out of a sci-fi novelist's wet dream. An anti-earth re-seamed together forming monstrous rings and topographies:   And there's more on Tarbell's website. (Via Drawn – with huge thanks to Brent Kissel!).

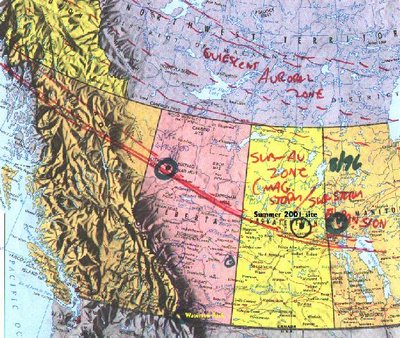

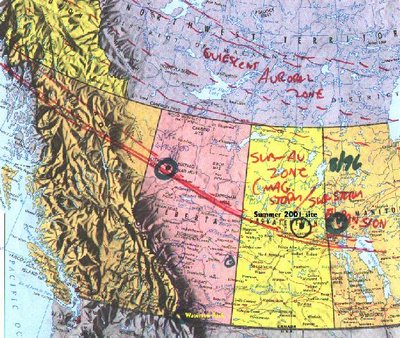

The "music of the magnetosphere" has been extensively recorded and catalogued by Stephen P. McGreevy, who once drove his dimunitive black van all over North America, antenna close at hand.  McGreevy hopes to capture "the sounds of Earth's fascinating, naturally-occurring audio-frequency radio signals" – elsewhere referred to as the "radio sounds of ' space-weather.'" Better yet, much of McGreevy's work can be downloaded for home listening.  Audible space weather appears, McGreevy explains, when energy from the sun "impacts Earth's Magnetosphere and generates lovely Aurora and Natural-Radio Signals." This topologically endless pressure-front between terrestrial energy and the radioactivity of the sun whistles, hisses and growls throughout McGreevy's MP3s.  The classicist inside me wonders: if Homer had made digital field recordings, wouldn't he, too, have sought these silent whisperings of the sun? Hymns from Apollo. What new myths exist at the ends of untuned antennas? And what the hell is that sound? This auroral chorus almost implies that birds imitate the sounds of space-weather every time they sing – but that claim clearly can't be substantiated while I'm typing into a laptop. (Can birds hear space weather? It's a legitimate question).  I actually find myself wondering at least two more things: 1) if humans had evolved just slightly differently, with different ears and skull structure, what catastrophic shiverings of distant galaxies might we hear? Eavesdropping on the sky, ablaze with endless whistling. Detonations of stars. Galaxial light. 2) Could you build a city that deliberately cultivates space weather? It'd use special metals in the frames of skyscrapers, and – if you did it right – the city itself would act as both antenna and loudspeaker, filling the streets with howls... If it worked, would anyone live there? This, for instance, is the sound of space weather above London – so perhaps it's possible to turn every city into vast canyons of white noise, neutron stars blasting empty avenues with sound. Forget light pollution – you'd hear London, hissing, unearthly, at the limit of the distant horizon. Sonic landmark. The sky – unplugged. (For vaguely related thoughts, see Aurora Britannica and Podcasting the sun).

A flying hotel has been proposed by Wimberley Allison Tong & Goo (but check out their space resort!), as part of a long-term campaign to design "entirely new kinds of destinations" – aka "successful destinations," leaving me, perhaps alone, to wonder what exactly an unsuccessful destination would be (a place at which you can never fully arrive...?).  WATG WATG has even published a PDF – made out to look like a manuscript illustrated by Leonardo da Vinci – explaining their vision of this and other surrealistically imaginative resorts: they're creating the hotel of tomorrow. (Can anyone say Archigram?)  Perhaps no one will be surprised by this, but I find the project totally fascinating – even if it is designed by an international tourism consultancy firm (an industry brilliantly satirized by Michel Houellebecq's novel Platform [not for everyone]). I'm still into this thing. In fact, BLDGBLOG could buy one of these hotels and move our offices permanently into the stratosphere. I'd look forward to it.  (Spotted at Interactive Architecture dot Org; see also Deep Space Hilton).

[Image: From the 2006 Venice Architecture Biennale]. The stated subject of this year's biennale is "the meta-city, an agglomeration that extends beyond the traditional form and concept of the city." I'm not entirely sure what I'm supposed to be looking at up there – but I like what I want to see in that image, which is either a reclaimed assemblage of highway overpasses, or a house built to look like an assemblage of highway overpasses. Either way, it's genius. Is it practical? Well, the ramps could be terraced, for starters, with floors at different levels, and steps cut into them, and toward the center of the cloverleaf could be a walled interior: bedrooms, bathrooms, a kitchen, guest rooms, all with floor to ceiling windows. A readymade, full-surround deck. Easy parking. Plumbing and electrics would come up through one of the concrete trunks – along with a staircase, through which to enter the house or visit your own backyard (or "underyard" – unless that's too Freudian). It's the house of the future: built like a highway overpass. Built on a highway overpass.     [Images: From the Freeway series by Catherine Opie]. I suppose it's not even outside the realm of possibility to imagine, several hundred years from now, after nearly everyone's died of bird flu, AIDS, or open civil warfare, that freeways – those massive examples of widespread land use, the world over – could be reclaimed, domesticated, built upon as new foundations. Houses in the midst of highway flyovers, cloverleaf junctions given windows, bedrooms constructed on off-ramps. New feudal worlds of elevated flyovers, towns held aloft in the sky. In Concrete Island by J.G. Ballard, we enter such a world, framed by drainage culverts, feeder roads, ascent ramps and storm tunnels, and we meet a man, called Maitland, who finds himself marooned after a crash, stuck alone in an urban blindspot: out of sight, out of mind, on an off-road island made entirely of concrete. "In his aching head the concrete overpass and the system of motorways in which he was marooned had begun to assume an ever more threatening size. The illuminated route indicators rotated above his head, marked with meaningless destinations." The man looks for "some circuitous route through the labyrinth of motorways" – but finds none. He simply sees "vast, empty parking lots laid down by the planners years before any tourist would arrive to park their cars, like a city abandoned in advance of itself." Indeed, Maitland, our new Crusoe of the London motorways, is "alone in this forgotten world whose furthest shores were defined only by the roar of automobile engines... an alien planet abandoned by its inhabitants, a race of motorway builders who had long since vanished but had bequeathed to him this concrete wilderness."  In any case, as freeways continue to form the only visible horizon for urban inhabitants worldwide, we may realistically find that houses soon come to look like them: back-looping knots of elevated platforms, curved nests of ramps that are suitable for living in, elevated over an empty world we've left behind.

[Images: Like posters for an unreleased horror film, it's the Holga photography of nicolai_g, taken from his Spacetime flickr pool. Good stuff!].

This is an old story, but I still like telling it. Japanese researcher Shun Akiba has apparently discovered " hundreds of kilometers of Tokyo tunnels whose purpose is unknown and whose very existence is denied."

[Image: From the LOMO Tokyo flickr pool; image by someone called wooooooo]. [Image: From the LOMO Tokyo flickr pool; image by someone called wooooooo].

Shun, who believes he is now the victim of a conspiracy, stumbled upon "an old map in a secondhand bookstore. Comparing it to a contemporary map, he found significant variations. 'Close to the Diet in Nagata-cho, current maps show two subways crossing. In the old map, they are parallel.'"

This unexpected parallelization of Tokyo's subway tunnels – a geometrician's secret fantasy – inspired Shun to seek out old municipal construction records. When no one wanted to help, however, treating him as if he were drunk or crazy – their "lips zipped tight" – he woke up to find his thighs sealed together with a transparent, jelly-like substance –

Er –

Actually, he was so invigorated by this mysterious lack of interest that "he set out to prove that the two subway tunnels could not cross: 'Engineering cannot lie.'"

But engineers can.

To make a long story short, there are "seven riddles" about this underground world, a secret Subtokyo of tunnels; the parallel subways were only mystery number one: "The second reveals a secret underground complex between Kokkai-gijidomae and the prime minister's residence. A prewar map (riddle No. 3) shows the Diet in a huge empty space surrounded by paddy fields: 'What was the military covering up?' New maps (No. 4) are full of inconsistencies: 'People are still trying to hide things.' The postwar General Headquarters (No. 5) was a most mysterious place. Eidan's records of the construction of the Hibiya Line (No. 6) are hazy to say the least. As for the 'new' O-Edo Line (No. 7), 'that existed already.' Which begs the question, where did all the money go allocated for the tunneling?"

Shun even "claims to have uncovered a secret code that links a complex network of tunnels unknown to the general public. 'Every city with a historic subterranean transport system has secrets,' he says. 'In London, for example, some lines are near the surface and others very deep, for no obvious reason.'" (Though everyone knows the Tube is a weaving diagram for extraterrestrials).

Further, Shun reveals, "on the Ginza subway from Suehirocho to Kanda," there are "many mysterious tunnels leading off from the main track. 'No such routes are shown on maps.' Traveling from Kasumigaseki to Kokkai-gijidomae, there is a line off to the left that is not shown on any map. Nor is it indicated in subway construction records."

Old underground car parks, unofficial basements, locked doors near public toilets – and all "within missile range of North Korea."

What's going on beneath Tokyo?

(Thanks to Bryan Finoki for originally pointing this out to me! For similar such explorations of underground London, see London Topological; and for more on underground Tokyo, see Pillars of Tokyo – then read about the freaky goings-on of Aum Shinrikyo, the subway-gassing Japanese supercult. And if you've got information on other stuff like this – send it in...)

The (infamous?) Central Park coyote "was finally captured at about 10 this morning near Belvedere Castle, after an officer with the New York City Police Department's Emergency Service Unit shot it in the rear with a tranquilizer dart."  [Image: A perhaps deliberately Soderberghian montage by Paul Kreft]. The coyote was "dubbed 'Hal' by some police officers and reporters because it was first spotted near the Hallett Nature Sanctuary" – but everyone knows it was really named after the rogue computer in 2001... The coyote is now being "rehabilitated" elsewhere, after surviving its first appearance in the animal-media storm. But it will be back... leading me to wonder: as the cities of the world purge themselves further and further of nonhuman species, will even a passing bird be treated as a public spectacle? (For a somewhat contrary view of beasts in the big city, of course, see Simian urbanism).

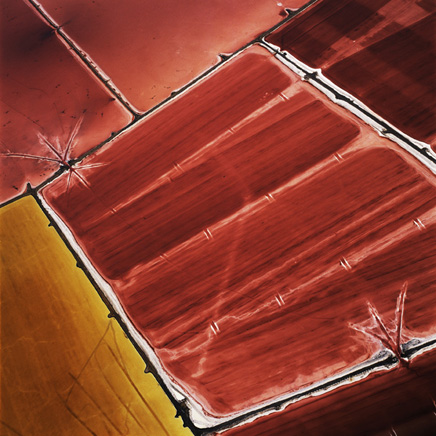

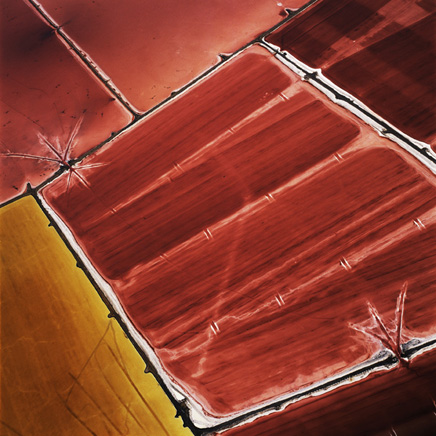

About two months ago I came across the photography of David Maisel, and I was instantly blown away. I started posting excerpts from his various photographic series up on BLDGBLOG – before he and I eventually got in touch.

So I decided to interview him for Archinect, another site I'm involved with, and the result of that decision was a lengthy and interesting telephone conversation, some email exchanges, and a visit to his studio out in Sausalito, CA (roughly 20 minutes after seeing the Bay Model).

That interview is now up and public.

If you get a chance, swing by and see some incredible images – and read about the draining of Owens Lake, the land art implications of mine leaching heaps, Icelandic hydropower, whether or not photographers are ever tempted to use pollution as a way to spice up an empty photograph... and much more.

The interview is here – and David's website is here. Enjoy!

If you could partially melt the city of London – then refreeze it: what might that new city look like? Alternatively, if you could build a huge machine, a landscape printer, and feed molten rivers of the city – a new Thames of liquid windows, old domes of churches running like paint – through its cavernous gates and printheads, what might you actually print with it? Could you use the molten city of London as an "ink" for future cityscapes – store it in a vat, and print new continuous bridges, endless architecture, from Kent to northern Yorkshire? A diagonal ribbon of liquid London, solidifying across all of France.  [Image: Instead of colors, you'd have a cartridge full of Islington, full of Holborn, King's Cross, Little Venice...]. (For a related idea, see magmatic architecture).

"Walking along the beach some years ago, I noticed a dark structure emerging from the mist ahead of me," J.G. Ballard writes in today's Guardian. "Three storeys high, and larger than a parish church, it was one of the huge blockhouses that formed Hitler's Atlantic wall, the chain of fortifications that ran from the French coast all the way to Denmark and Norway. This blockhouse, as indifferent to time as the pyramids, was a mass of black concrete once poured by the slave labourers of the Todt Organisation, pockmarked by the shellfire of the attacking allied warships."  This wall of now abandoned concrete bunkers, Ballard tells us, was but part "of a huge system of German fortifications that included the Siegfried line, submarine pens and huge flak towers that threatened the surrounding land like lines of Teutonic knights. Almost all had survived the war and seemed to be waiting for the next one, left behind by a race of warrior scientists obsessed with geometry and death."  [Image: Richard Doody]. Ballard then climbs into one of the ruined blockhouses, and finds it reminds him "of the German forts at Tsingtao, the beach resort in north China that my family visited in the 1930s. Tsingtao had been a German naval base during the first world war, and I was taken on a tourist trip to the forts, a vast complex of tunnels and gun emplacements built into the cliffs. The cathedral-like vaults with their hydraulic platforms resembled Piranesi's prisons, endless concrete galleries leading to vertical shafts and even further galleries. The Chinese guides took special pleasure in pointing out the bloody handprints of the German gunners driven mad by the British naval bombardment."  [Image: Richard Doody]. And so on – we meet Modernism, ornament, Stalin, Hitler, London's National Gallery, the high-rise architecture of death and class warfare: read more at the Guardian. Of course, in The Rings of Saturn, W.G. Sebald takes us on a walking tour of the English coast, including Britain's own military landscapes. These abandoned weapons testing ranges, complete with odd concrete structures, Sebald writes, looked like "the tumuli in which the mighty and powerful were buried in prehistoric times with all their tools and utensils, silver and gold. My sense of being on ground intended for purposes transcending the profane was heightened by a number of buildings that resembled temples or pagodas, which seemed quite out of place in these military installations. But the closer I came to these ruins, the more any notion of a mysterious isle of the dead receded, and the more I imagined myself amidst the remains of our own civilization after its extinction in some future catastrophe."  [Image: Keith Ward]. For Sebald, "wandering about among heaps of scrap metal and defunct machinery, the beings who had once lived and worked here were an enigma, as was the purpose of the primitive contraptions and fittings inside these bunkers, the iron rails under the ceilings, the hooks on the still partially tiled walls, the showerheads the size of plates, the ramps and the soakaways." It is interesting to note that both Sebald and Ballard discuss an isle of the dead –  [Image: Arnold Böcklin, Isle of the Dead, 1883]. – specifically, in Ballard's case, Arnold Böcklin's famous 1883 painting of that title. In any case, you can also take a look at the site Atlantik Wall for more images and history; you can follow Subterranea Britannica's journey into some weird missile silos –  [Image: Nick Catford]. – built into the landscape of northern France; you can read Paul Virilio's now somewhat legendary exploration of abandoned WWII landscape architecture, Bunker Archaeology; and you can take a brief look at the observations made here, as part of a larger architectural travelogue that begins in London's Barbican. Of course, you can also take a look at an art project, from 1998, by Magdalena Jetelova –  – in which she laser-projected select quotations from, what else, Paul Virilio's Bunker Archaeology onto the half-submerged fortifications found scattered along Normandy's beaches.  Finally, here's a good interview with J.G. Ballard; and, though irrelevant to bunkers, I recommend Ballard's Super-Cannes in the highest possible terms. (Though it's certainly not for everyone who reads BLDGBLOG).

|

|

[Image: Australia's

[Image: Australia's  [Image: The reefs of Raiatea and Tahaa in the South Pacific;

[Image: The reefs of Raiatea and Tahaa in the South Pacific;  [Image: The Pearl and Hermes Atoll, NW Hawaii, via

[Image: The Pearl and Hermes Atoll, NW Hawaii, via  [Image: Saxophone valve diagram by

[Image: Saxophone valve diagram by  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:

[Image: From the

[Image: From the