|

|

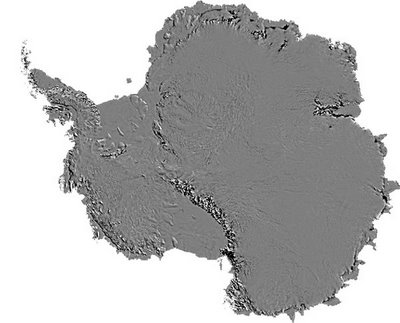

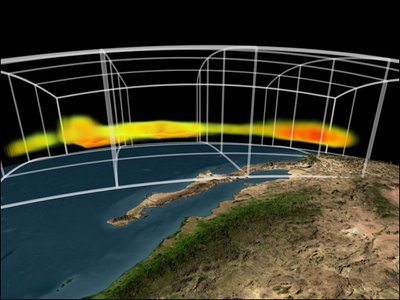

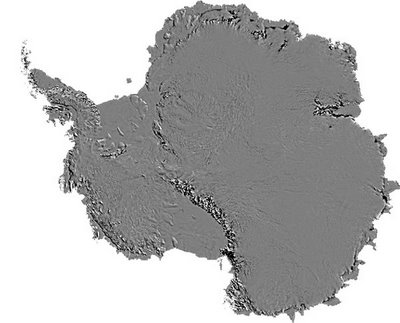

[Image: Courtesy of NASA's Earth Observatory]. There are a wide variety of overlooked and forgotten ways in which humans participate with, and alter, the biological systems around them. A few seeds, trapped in the soles of our shoes, can cross oceans with us in airplanes, bringing gardens, and weeds, and parasite species, to the other side of the earth; trace amounts of infectious diseases can cling to our clothes and decimate livestock several nations away; snakes, rats, spiders, mosquitoes – all can easily ride the ships and planes of globalization. Our economy is crowded with invasive stowaways intent on surviving elsewhere – even if survival means irretrievably altering the new host environment. In other words, travel itself can be something of a biological activity: we do the migratory work of other species for them. We take them with us. Importations of even the smallest microbe can sufficiently alter an ecological niche, opening it up to further changes – then compounding over time into whole new landscapes. What would happen naturally is accelerated: a thousand years in a decade. It shouldn't surprise us, then, to learn that strange things are afoot in Antarctica. (To read more, you'll have to visit WorldChanging – for whom this post was originally written).

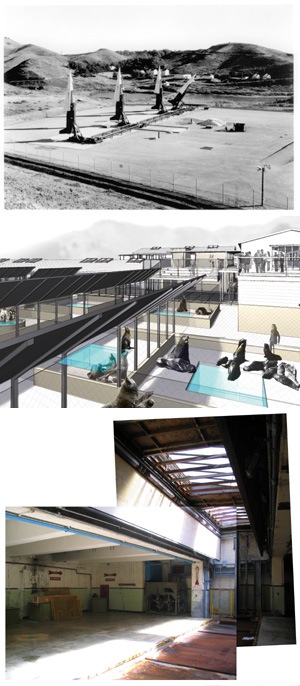

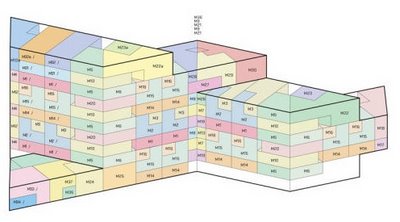

For an exhibit during last month's London Architecture Biennale 2006, curator Matteo Cainer invited "architectural studios from outside the UK (...) to sketch a visionary project for London." Graphic speculation about another London yet to come, Cainer hoped, would "further consolidate architecture’s role in imagining a future for the city": Architects have been invited to take an outsider’s view, and as such submit a sketch for an imaginative project in the city of London. They are free to choose a site and focus, whether addressing issues of planning, landscape, infrastructure or building. The central challenge remains what it has been for centuries: to make architecture a vessel for new and controversial ideas. Gathering together architects with sketches, and critics with words, will entice visitors into a theatre of architectural imagination where a wide range of daring projects, conceived by some of the most inventive and newly emerging architects, come together in a panorama of architecture’s current potential and promise. This will in turn create a platform for discussion and a critical examination of today’s approach to architecture. The result was The World in One City – A Sketch for London, an exhibit beautifully designed by Cainer's own Design Research Studio at Fletcher Priest Architects.   [Images: © Chris Gascoigne]. After emailing Cainer expressing interest in the exhibit itself and in the architectural projects it featured, he responded with a PDF from which these images were taken. Here we see interior shots, offering a glimpse of the show's dominant theme: coordinate points of latitude and longitude, geographic sites of architectural speculation.    [Images: © Chris Gascoigne]. "The show tries to move beyond the current scene, dominated by cyberspace and video simulation," Cainer explains, "and beyond the familiar client restraints and the fashion parade of magazines." Instead, the exhibit's purpose is to focus on "the ‘sketch’ as the fulcrum of architectural imagination. Concepts and subsequent sketches are often underestimated: sketching is not only practical but also essential; it is the quickest, most accessible way for generating ideas." A website for the show is in the works, as well as a publication. Finally, let me just add that the idea for this exhibition is totally fantastic, and that every city in the world, frankly, should perform this kind of imaginative self-reflection at least once every few years. By openly speculating about conjectural urban futures – whether those include pedestrian malls, blimp-aquariums, or even insanely ambitious green roof projects – residents of cities everywhere can be reminded that their own urban environment is an ongoing project, and that everyday life itself can be upgraded, reprogrammed, better designed. After all, the architectural future is just a few words and sketches away. (Note: All photographs in this post are by Chris Gascoigne – whose website is chock full of more architectural photography).

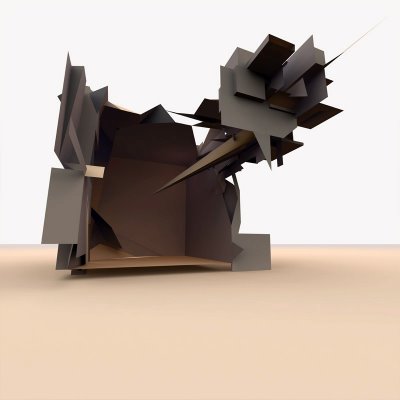

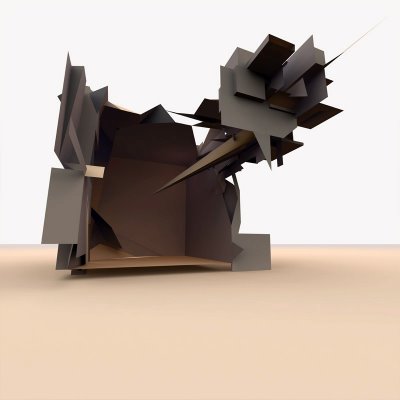

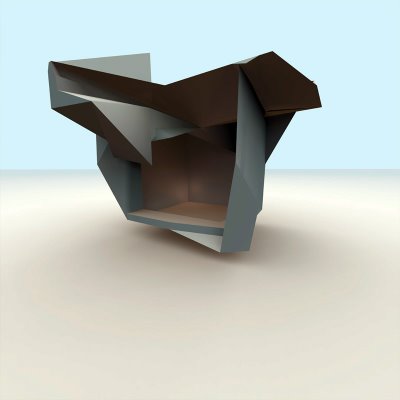

[Image: From Spam Architecture, © Alex Dragulescu]. Alex Dragulescu has some extremely interesting projects up on his website right now. For the most part, they're "experiments and explorations of algorithms, computational models, simulations and information visualizations that involve data derived from databases, spam emails, blogs and video game assets." However, this one – called Spam Architecture – totally blows me away: "The images from the Spam Architecture series are generated by a computer program that accepts as input, junk email. Various patterns, keywords and rhythms found in the text are translated into three-dimensional modeling gestures."  [Image: From Spam Architecture, © Alex Dragulescu]. Applying this to large-scale architectural design would be endlessly and hypnotically fascinating – not to mention quite profitable if you turned it into a kind of immersive, 3-dimensional version of Tetris. You turn digital photographs of your last birthday party into architectural structures; your Ph.D. thesis, exported as an inhabitable object; every bank statement you've ever received, transformed into a small Cubist city. Your whole DVD collection, informationally re-presented as a series of large angular buildings. Of course, you could also reverse the process, and input CAD diagrams of a Frank Gehry building – thus generating an inbox-clogging river of spam email. The Great Wall of China, emailed around the world in an afternoon. The collected works of Frank Lloyd Wright. In any case, Dragulescu currently works at the Experimental Game Lab at UC-San Diego – the same institution at which Sheldon Brown developed his Scalable City project. (Thanks to Brent Kissel for the tip about Dragulescu – and you can read more here – and to Brian Romer for Scalable City).

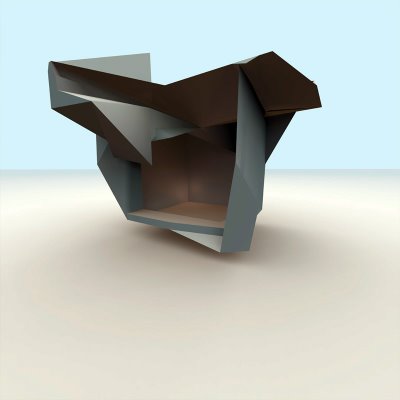

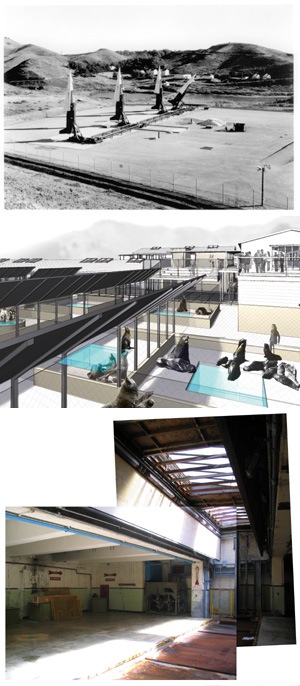

The Marine Mammal Center (MMC) in Sausalito, California, treats elephant seals injured by "shark bites, gunshot wounds, and untenable toxins in their liquid habitat," Architecture magazine explains. "Half of all injured pinnipeds and cetaceans found in the United States – typically 700 over recent years, mostly reported by vigilant fishermen – are treated here." More relevant to the present website, however, the MMC is now receiving a much-needed, multi-million dollar architectural upgrade – and the new design fascinatingly incorporates a derelict "pair of Nike missile silos."  [Image: Architecture Magazine]. "A dozen anti-aircraft missiles were first secured here in two 3,000-square-foot underground berths," Architecture tells us. "Soon, one of those deep concrete wells will contain all of the hospital facility’s water processing equipment, keeping it away from the sun’s damaging rays and freeing the territory above ground for recovery functions... The other silo will contain long-term freezer storage of animal tissue specimens for study." Let's hope neither of them accidentally go off. Of course, reusing missile silos for architectural purposes is nothing new – and, in skimming the original article, I actually thought the silos would be turned into functioning aquariums – but the project still works as a brilliant engagement with existing site conditions. You can see one or two more images of the design at the website of Gyroscope, Inc., the project architects –  – where, for instance, we find the above diagram. "Because the center operates around the clock," Architecture explains, "illumination for night had to be directed in a manner sensitive to the fact that animals in the bay use light for migration. A portion of the pools will always be shaded by overhead awnings – many of which will be lined with photovoltaic panels, thanks to a generous donor – giving the animals a choice of where to hang out, and cutting down on cooling costs." On the other hand, at least one question remains: seeing as how the missile silos will not be turned into functioning aquariums, is there an aquarium avant-garde anywhere else – and, if so, what does it look like? My provisional vote is for a series of truly gargantuan blimps dragging huge, transparent, cable-tethered aquariums full of coral reefs, fish, and blue whales through the skies of Baghdad. The insurgency might end right then and there: dazzled, confused, feeling touched by the miraculous, the only thing the militias will know how to do is just put down their guns – and stare.

In April 2006, a city-wide writing program began in Philadelphia. Called the Autobiography Project, the program's basic idea was to invite residents of the city to tell ther own life stories – or simply individual stories taken from their lives – using 300 words or less. The Project even sponsored community writing workshops for those Philadelphians unsure of their literary abilities – and some workshops were so successful that similar such groups may become regular fixtures at the institutions involved. More than 340 memoirs were submitted over a six-week period. A panel of local writers and cultural figures then chose 20 particularly memorable autobiographies, and these were printed as full-size posters, complete with a photograph of each author, and installed within bus shelters throughout the city. The posters were taken down on July 23rd. You can read more about the project at WorldChanging, where this post was originally published.

[Image: A partially inflatable immigrant-detention center, photographed by The New York Times – though their article is now pay-per-view]. Between statelessness and Westphalian sovereignty you apparently get inflatable architecture, instant cities on the carceral edge between two systems of power: "As the Bush administration gets tougher on illegal immigration and increases its spending on enforcement," the New York Times reported last week, "some of the biggest beneficiaries may be the companies that have been building and running private prisons around the country." This is referred to as the "detention market," and it is "projected to increase by $200 million to $250 million over the next 12 to 18 months" – an astonishing increase of 400%. (Invest now).These "beds within the border region" are managed with Wal-Mart-like efficiency. Indeed, making beds "available quickly is considered an advantage in the industry since the government’s need for prison space is often immediate and unpredictable. Decisions about where to detain an immigrant are based on what is nearby and available. Immigration officials consider the logistics and cost of transportation to the detention center and out of the country." All of which defines a new political space wherein real-time logistics, transport infrastructure, the rise of the market-state, private investment, and post- Archigramian inflatable architecture strangely merge. Two quotations seem appropriate here, both taken from Philip Bobbitt's recent – and extraordinarily dense – look at historical mutations within the concept and practice of constitutional sovereignty. As the nation-state is superceded by the market-state, Bobbitt explains, we are witnessing a clash of tactical responsibilities: "What is appropriate for the market-state – with its porous territorial concepts and its responsibility to preserve the opportunities for personal development, including, of course, access to a safe environment – seems to clash with the absolute sovereignty of a nation-state taking steps it alone can determine are necessary, within its territory, to protect the nation." Of course, this is exactly what we see today in the U.S. immigration debate: an argument for the economic necessity of immigrant labor, including financial opportunity for all, vs. an argument for national border security and the protection of legal citizens. "There is a grotesque disparity," Bobbitt writes, "between the rapid movement of international capital and the ponderous and territorially circumscribed responses of the nation-state, as clumsy as a bear chained to a stake, trying to chase a shifting beam of light." The almost Dr. Seussian world of inflatable immigrant-detention camps, as explored by The New York Times, is perhaps evidence of this sovereign clumsiness. (The NYT article was also covered by Bryan Finoki over at Subtopia; meanwhile, a rather old BLDGBLOG post explores the idea of " criminal aliens needing beds").

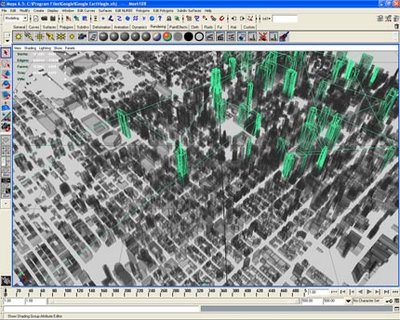

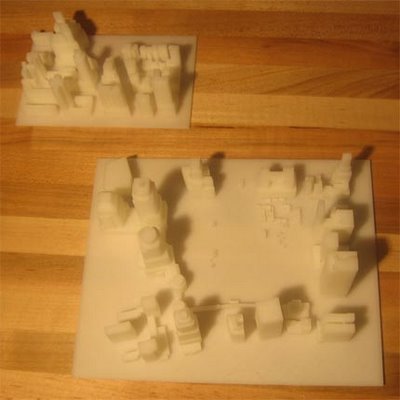

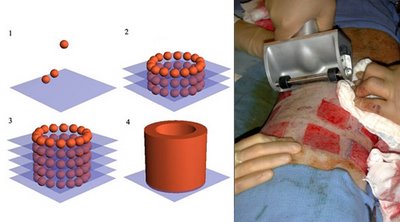

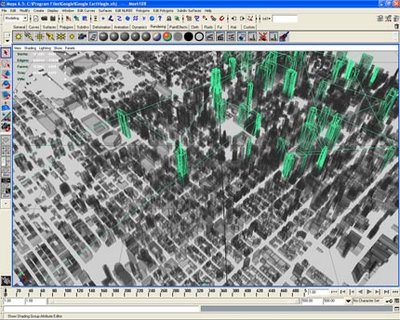

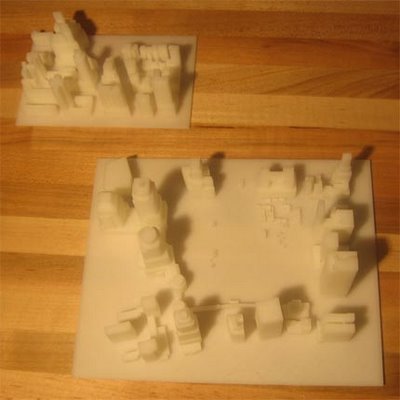

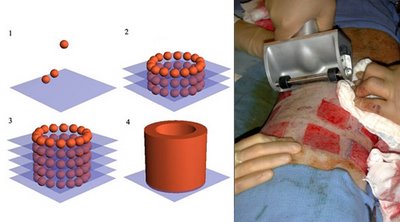

[Image: "The Polecat UAV is pictured flying at 15,000 feet by a chaseplane. Polecat's airframe was 'laser printed' rather than machined." New Scientist Tech]. The same week we found out that jets of the future will be made with plastic, we also read that the U.S. military has been working toward printable airplanes – unmanned drones made by "rapid prototyping." As New Scientist Tech reports: "In rapid prototyping, a three-dimensional design for a part – a wing strut, say – is fed from a computer-aided design (CAD) system to a microwave-oven-sized chamber dubbed a 3D printer. Inside the chamber, a computer steers two finely focussed, powerful laser beams at a polymer or metal powder, sintering it and fusing it layer by layer to form complex, solid 3D shapes." Of course, 3D printing is nothing new; several months ago, for instance, just about everyone in the universe learned that 3D buildings and cityscapes can be printed using images from Google Earth.    Even more strangely, you can also print fully-functioning body parts using "droplets of 'bioink'," which are "clumps of cells a few hundred micrometres in diameter." In other words, if you "alternate layers of supporting gel, dubbed 'biopaper', with the bioink droplets," and if you "build tubes that could serve as blood vessels, for instance," then, through bio-printing, these will become the "successive rings containing muscle and endothelial cells, which line our arteries and veins."  This Frankenstein-meets-Hewlett-Packard technology can be used to "print any desired structure." Indeed, there are now "printing heads that extrude clumps of cells mechanically so that they emerge one by one from a micropipette. This results in a higher density of cells in the final printed structure, meaning that an authentic tissue structure can be created faster." (What about a photocopier?) Finally, skeptics will benefit from learning that "cells seem to survive the printing process well. When layers of chicken heart cells were printed they quickly begin behaving as they would in a real organ. 'After 19 hours or so, the whole structure starts to beat in a synchronous manner.'" (A bit more on this here). The Oliver Twist of tomorrow, then, will be a poor boy, printed in obscurity... So the question naturally arises: what if you were to combine all these? You'd get a vast, self-printing city-organism, whose skies are criss-crossed with machine-birds of prey; when buildings reach the age of senility, forgetting how many floors they contain, they are melted down into rivers of ink and pooled in living reservoirs to be printed once again; molds and fungi and architectural infections bloom, growing atop one another till new parasite structures form, small Gothic rooms in which the homeless live. All of which reminds me, somewhat disjunctively, of the following rather unoriginal statement: the default condition of all literary genres will soon be science-fiction. You simply will not be able to write about the world without incorporating these weird new technologies. Science-fiction and social realism will become one and the same thing. Look at the recent genre-defying work of Kazuo Ishiguro, Michel Houellebecq, David Mitchell, Rupert Thomson, Alex Garland; soon even Ian McEwan will be writing sci-fi. Note, as well, that whilst mainstream American literary novelists appear increasingly incapable of doing anything other than reimagining their own national past – Philip Roth, say, or the forthcoming Thomas Pynchon – as if endlessly recycling historical micro-narratives will result in something new – Anglo-European fiction appears to have accepted, with great success and enthusiasm, the futurist inclinations already so obvious in everyday life. To be rather broad here – for instance, does Michael Cunningham invalidate my argument? do I even have an argument? – it seems that while British fiction in particular has already accounted for the slippage of contemporary life into sci-fi, even welcoming this phenomenon with a newfound literary ambition, mainstream American fiction is content simply to enroll itself in unnecessary MFA programs, writing 800-page novels about family farms, the period between WWI and II, shopping, or the supposedly "atmospheric" end of the 19th century. Run-of-the-mill student architectural proposals are already more stimulating than most of today's American novels. Architectural proposals have ideas. Meanwhile, the rest of the world has already discovered the future, and it's no real wonder that the U.S. publishing industry is in the midst of a kind of slow financial crisis. In fact, you only have to look at the ongoing revival of interest in Philip K. Dick – sci-fi novelist and volunteer FBI informant – to see that Americans don't exactly lack a literary taste for the future; it's just that all the wrong novels keep getting published here. In any case, there are a million exceptions to this argument; feel free to rip it apart. For example, where does The Da Vinci Code fit in all this? Etc. etc.

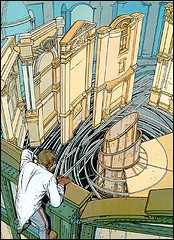

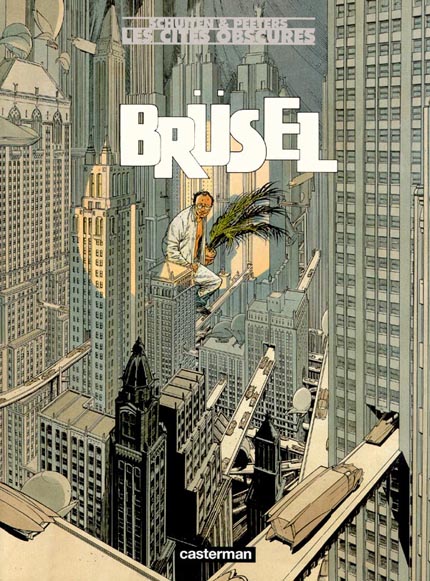

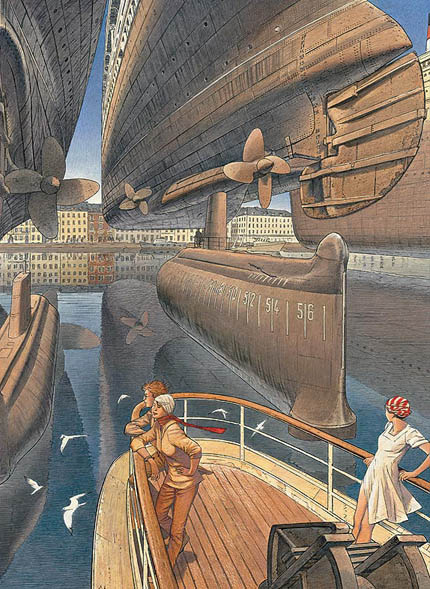

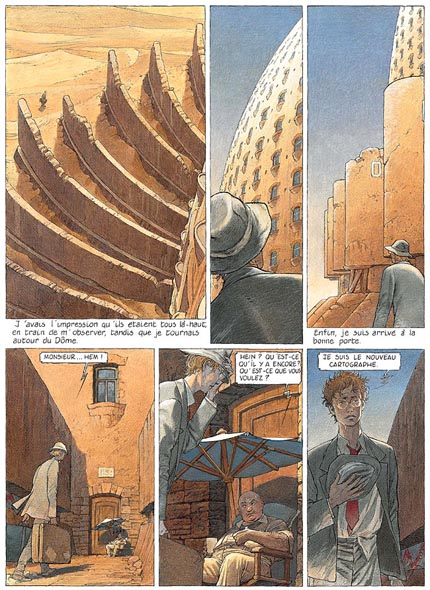

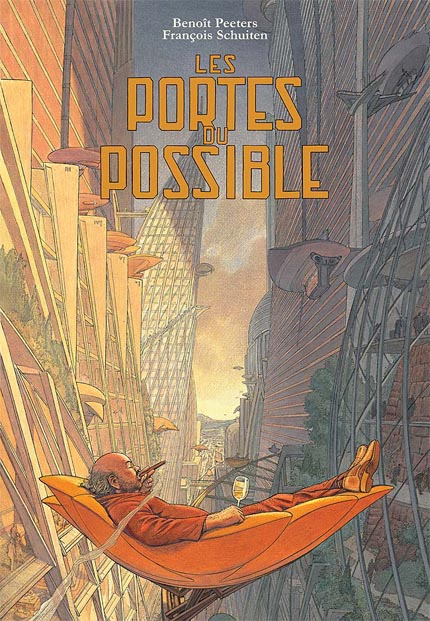

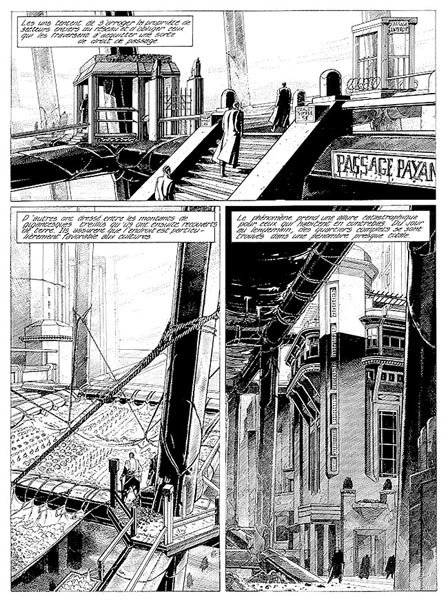

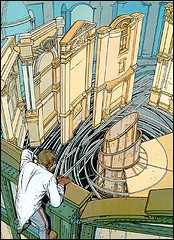

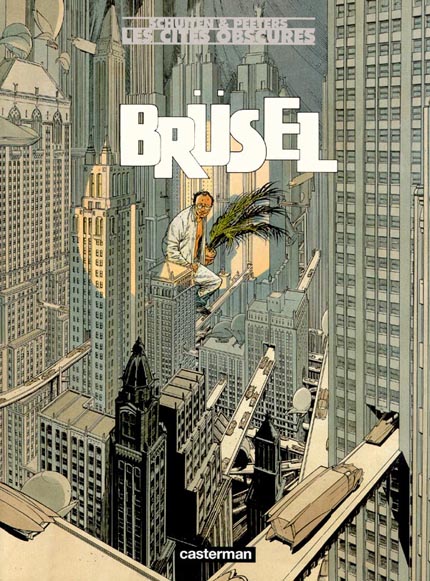

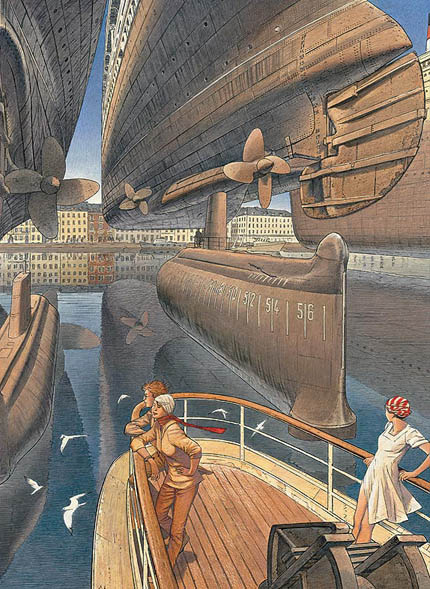

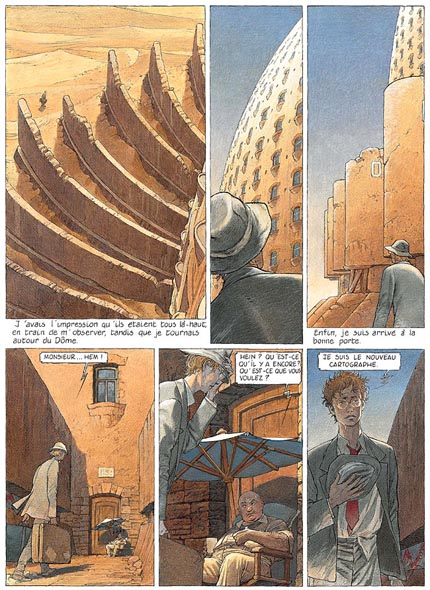

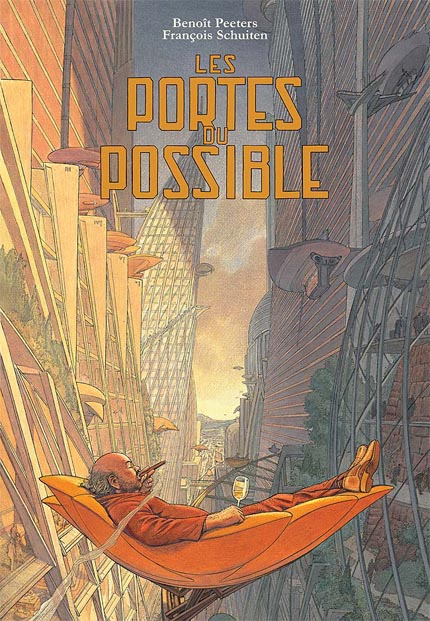

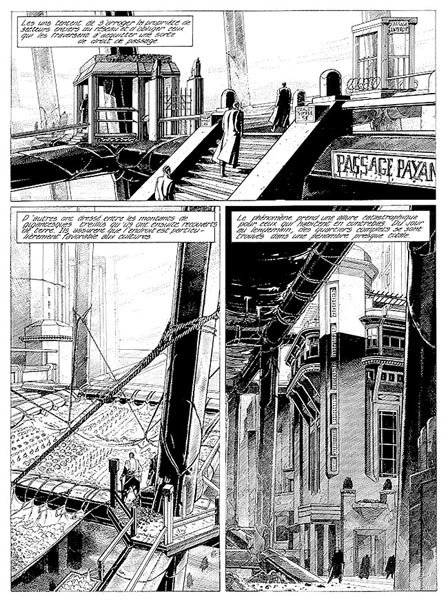

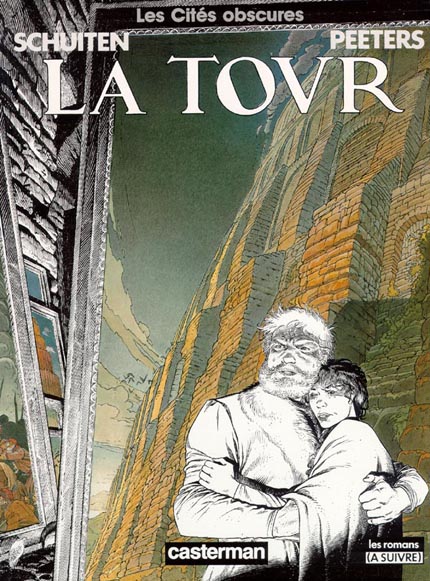

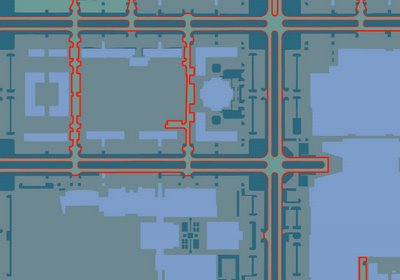

These images are spatio-structural urban fantasies taken from Urbicande. Les cités obscures, the source material, is a 12-volume graphic novel by François Schuiten and Benoît Peeters, in which "references to our world abound, especially in regard to architecture." It is a " parallel universe," we read, full of utopian construction projects and urban expeditions, strange villages and—

—moving machine-labyrinths made from decontextualized walls. Its "coherence is constantly growing with time."

All images, including those below, are copyrighted by and fully credited to this creative team.

(Thematically related: gravestmor introduces us to The Mysterious Geographic Explorations of Jasper Morello, and Pruned gives us some Brodsky & Utkin. In the process, don't forget BLDGBLOG's own look at cinematic urbanism, or Archidose's reconsideration of the strangely inspiring film, La Jétee).

(Thematically related: gravestmor introduces us to The Mysterious Geographic Explorations of Jasper Morello, and Pruned gives us some Brodsky & Utkin. In the process, don't forget BLDGBLOG's own look at cinematic urbanism, or Archidose's reconsideration of the strangely inspiring film, La Jétee).

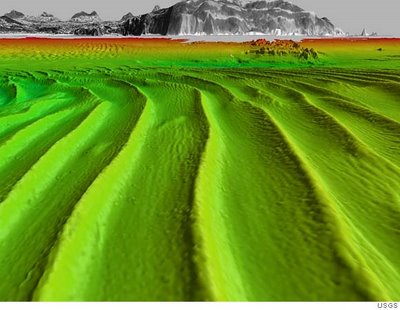

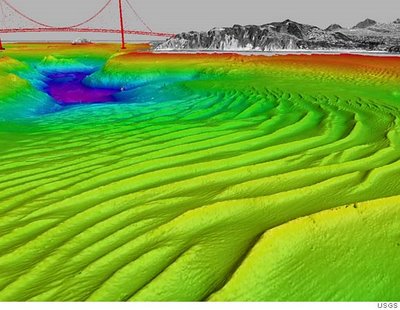

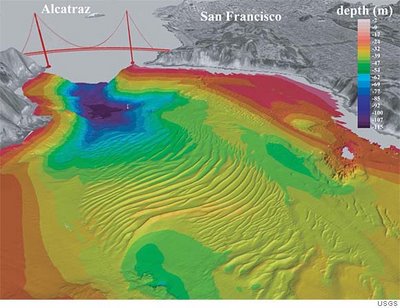

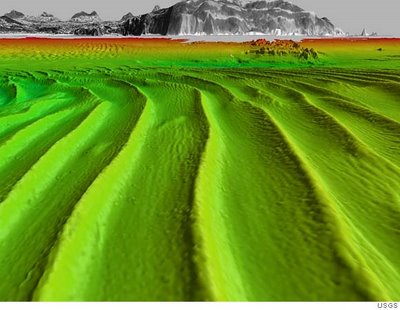

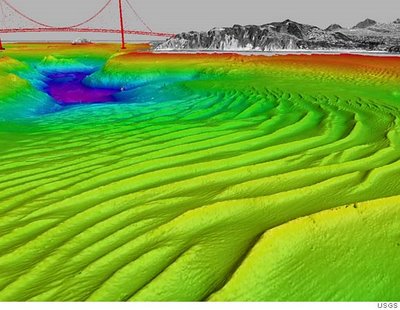

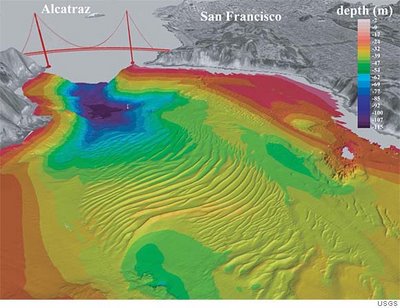

From today's San Francisco Chronicle: "'These are some of the largest sand waves in the world,' said Patrick Barnard, a coastal geologist with the Santa Cruz office of the U.S. Geological Survey. 'They're certainly in the upper 10 percent.'" Unfortunately – or perhaps more interestingly – they're underwater, lining the bottom of San Francisco Bay like tectonic corrugation: "The sand waves range up to 700 feet long and reach heights of more than 30 feet, Barnard said. It is a dynamic system, he said, with the configuration of the individual dunes changing significantly with each tidal cycle. But overall and over time, the net change to the entire field is slight." In that regard, and if you were pretentious, you could say that the landscape inhabits a kind of fractal temporality...  As it is, "scientific interest in sand waves has been growing around the world because sonar technology has improved to the point that high resolution, three-dimensional maps can now be made of the ocean's floor" – which was actually explored in an earlier post on BLDGBLOG: The Geoacoustic Sea.  There we read the following: "It'd be interesting, meanwhile, if you could take geoacoustic data and release it as an MP3: you could then listen to the suboceanic landscape's raw sonic topography, compressed aquatic echoes, complete with deepsea ridges and audio-thermal vents. Non-visual mapping of unreachable landscapes. An MP3 of the surface of Mars. The rings of Saturn." And now we've read it again – because, for the record, I still think it'd be interesting. After all, if you can't actually visit the landscape, you could simply download it as an MP3... Audio geotechnics. Or convective audio cartographies, 3D podcasts of unexplored worlds. (Thanks to Bryan for the tip!)

"You may not know his name," the New York Times wrote four years ago, "but you have probably enjoyed the public spaces he has created." He is Ken Smith, " the Elvis Costello of landscape architecture." "Perhaps," the Times continues, "you sat on an Art Deco bench and admired the Islamic geometric patterns of the paving stones at Malcolm X Plaza in Harlem or walked through the Glowing Topiary Garden he and Jim Conti, a lighting designer, installed three years ago at Liberty Plaza for the winter solstice. If you've been to Toronto, you may have walked through his idiosyncratic Village of Yorkville Park, with its 700-pound rock and miniforests and the rain curtain that freezes into icicles in winter." Smith, we read, has a "Seussian mind," which means that he freely combines glass elevators with bamboo gardens – moving, earthless landscapes; horticultural Cubism – and he adds "glacial hummocks, grasslands, [and] honey locusts," even while opening up space for ice skating. And so on. But what interests me here are Smith's so-called Dumpster Gardens, where you take a dumpster – or skip, if you're British – and grow a garden in it. Portable landscapes. In 2003, Smith installed three such Dumpster Gardens at Ohio State University –     – as these photographs attest. "Each of the three Dumpsters houses different plant life," Ohio State University's student newspaper tells us. "One contains a fragment of lawn and a second has juniper shrubbery and river birch. The third stands in front of Ohio State President Karen A. Holbrook's office with a bed of scarlet (celosia) and gray (artemisia) flowers. (...) Each of the Dumpsters is three feet deep and 20 feet long. The bottom is covered with gravel to allow for drainage and the rest is filled with planting soil." But Smith's dumpsters are not doomed to spend the rest of their days in the empty, mausolean fate of decorating university campuses; indeed, returning to the New York Times: "Dumpsters would also be a great way to enliven traffic medians, Mr. Smith said. 'You could grow corn, or have a portable meadow of Queen Anne's lace and juniper,' he suggested." Of course, you could also link them all together into a walled labyrinth, a postmodern hedge maze that twists and meanders through the city; you could grow hybrid flowers and Aspen trees, poisonous fungi and ergotic growths, in others, a kind of dumpsterized botanical taxonomy; you could tow gardens all over the country, even, driving every mile of the US highway system (and terrestrially out-performing Robert Smithson in the process); you could ship the things to the middle of the Atlantic Ocean where they'd be permanently anchored, forming tax havens, utopian atolls, a new Earth; or, better yet, you could skip the dumpsters outright and use enormous wicker baskets: plant amazing and weird asymmetrical gardens in each, then attach them to hot-air balloons – bulletproof, Artificially Intelligent hot-air balloons. Set them loose in the sky. Aerobiology.  Gardens drift slowly above your head on trade winds, trailing creeper vines; a jellyfish, made of kudzu, flying through the stratosphere. New weed species auto-hybridize, evolving super-seeds, and they re-invade the earth from above. Literal new levels of biological warfare. Hugo Award-winning novels are written, documenting the vegetative horrors. One of the balloons then crashes in the forests of Papua New Guinea and, instead of a cargo cult, you find a cult of landscapes-that-fall-out-of-the-sky. Gardens in a space capsule. They re-enter Earth's atmosphere and crash outside London 5000 years from now. Ken Smith is there to greet it – turns out it was his idea in the first place... In any case, Smith also has a book. More info on some of his other projects here and here and here.

Two years ago, Young's brewery began producing bottles of Kew Brew, a beer made from rare hops grown in London's Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew. And preserving endangered landscapes by turning them into alcoholic beverages sounds like a good idea to me...  "Sales [of the beer] will help Kew’s conservation work as a donation per bottle is given to the Gardens which runs the international Millennium Seed Bank Project." Not everyone likes the taste, of course, but the beer is, at the very least, an amazing idea; from the perspective of landscape design and preservationist horticulture, it's even brilliant. Avant-gardeners will soon forget all about topiary mazes – and install huge vats of beer instead. Liquid gardens you internalize. Indeed, one wonders what other plants could be rescued from the brink of extinction simply for the purpose of becoming beer: extinct ferns, perhaps, cloned from scraps of DNA, are fermented in bottles of Jurassic Park Pale Ale... Rare African orchids, saved from planetary disappearance, aromatically flavor BLDGBLOG's new Lost Eden Stout. Hybridized roses suddenly explode in genetic vitality due to the appearance of Pruned's Meta-Botanical Bitter. Next up: architectural historians join in. Condemned Futurist masterpieces are ground up and served as salt at French dinner parties. You may not save the building – but you can season your shrimp with it... Stuff sausages with Philip Johnson. The Building Burger. Ionic Pie. (With thanks to Nicky!)

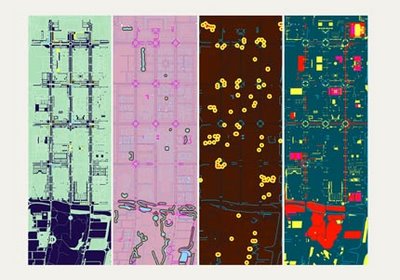

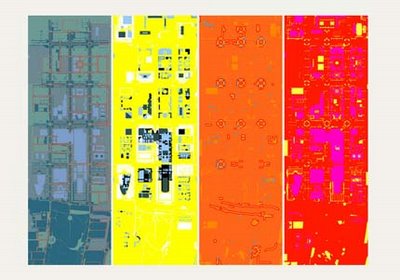

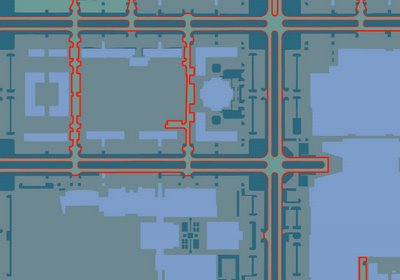

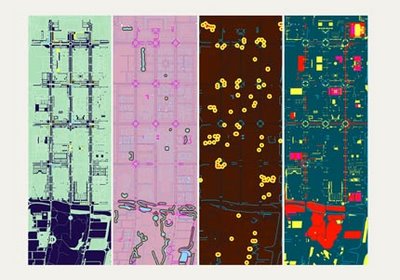

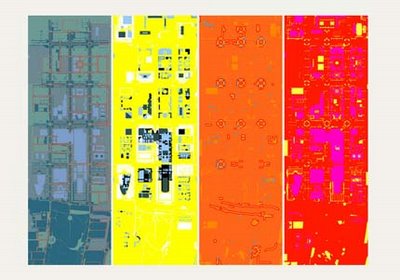

"My Psychoacoustic Maps of Milton Keynes explore ways of translating visual compositions into sound environments," Timon Botez of the London-based design firm CO-Designers writes. Botez is describing an event and exhibition he organized as part of last month's Architecture Week 2006, hosted in London.  "I have composed a series of maps based on colours I like," he continues. "The maps are visual environments, snapshots of a time of day, a mood or an experience in Milton Keynes. I have built a software that analyses the images and produces sound based on the colours. This forms the basis for the audio compositions that accompany the maps. The psychoacoustic maps are not functional, but they use the geometrical forms of the original city map as a basis for artistic expression."  Some of the audio tracks are quite mesmerizing; but if you don't like drumless electronic space or digitally glitched crackling background drones, then Botez's shudder-filled sci-fi audio-maps of Milton Keynes are probably not for you. But I particularly like the track called FridayEvening (or FridayEvenening, if its file name isn't a typo): here's the MP3. There's also Commute1 ( MP3) and Sunday2 ( MP3) – as well as five others, all available here. At the very least, you can irritate dogs with them... To some extent, though, Botez's project reminds me of two other urban-acoustic works. One is a piece called Surface Noise, by Scanner, which used one of London's old double-decker buses as an acoustic focus. "Making a route determined by overlaying the sheet music from London Bridge Is Falling Down onto a map of London," Scanner writes, "I recorded the sounds and images at points where the notes fell on the cityscape. These co-ordinates provided the score for the piece and by using software that translated images into sound and original source recordings, I was able to mix the work live on each journey through a speaker system we installed throughout the bus, as it followed the original walk shuttling between Big Ben and St Paul’s Cathedral." The MP3s are downloadable from Scanner's site (scroll down), but certainly nothing to rush out for. The other project I'm thinking of is an old CD-R called .murmer, released by Patrick McGinley. As McGinley himself explains, studiously avoiding upper-case letters, because only Fascists capitalize: "the source recordings for .murmer were all taken during my first six months as a resident of the city of london. hence they document my exploration and discovery of a new home, as well as of a new medium. i purchased my first recorder and microphone upon arrival here, and began exploring their possibilities alongside exploring the city. however, these sounds are not a portrait of a location; i made no attempt to map a geography. they are more personal. many originate from within my private space (the refrigerator and grill provided in a bedsit; the wind through an apartment window) and all are tied strongly to my personal movements (the air vent on my local bus, the heater in my place of work)." And so on. Accordingly, McGinley's track ".errum" was made using the following urban sources: "air vent on a 73 bus, malfunctioning gas heater, feedback, escalator at pimlico tube station." Meanwhile, McGinley's photo diary –  – of which the above are several examples, apparently documents some of the more landscape-architectural references in his work; and his radio show – featuring "contextual and decontextualized sound activity" – can also be downloaded or streamed. Finally, here are links to McGinley's own music; it's sparse stuff, but not bad if you simply want acoustic company. The track " .meurm" (MP3), for instance, was built entirely from the mechano-solipsistic moan of McGinley's refrigerator and gas grill (as mentioned above). Soundtracks for architecture, indeed. (Earlier: Urban sound walks and How to podcast a landscape).

[Images: "In & Out" and "In the City" by Fabrice Fouillet; images originally purchased as postcards last week in Paris – though easily found online. There is also his " RDV." (Very vaguely related: Xing Danwen's Urban Fiction, via WMMNA)].

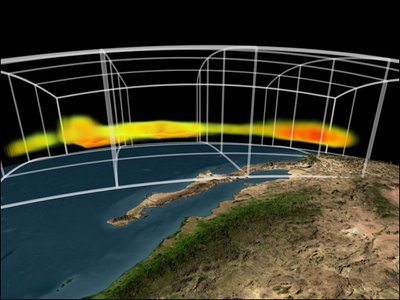

[Image: Graphing storms. This is the "3-D structure of a storm’s water vapor content," as it approaches southern California. Also available in a huge 1.2MB version. Courtesy of – where else? – NASA's Earth Observatory].

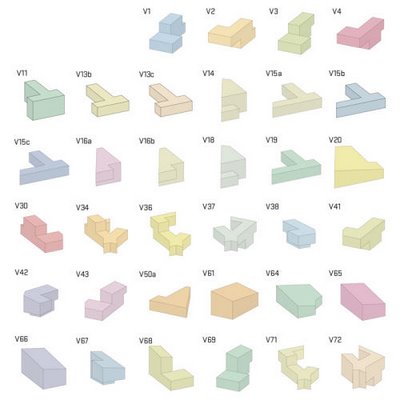

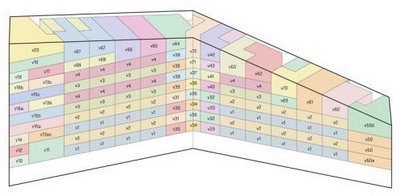

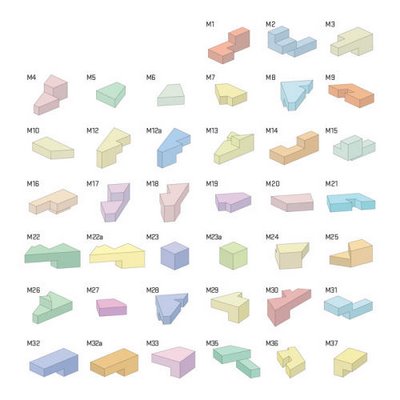

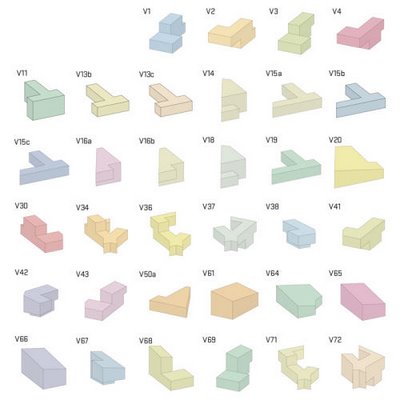

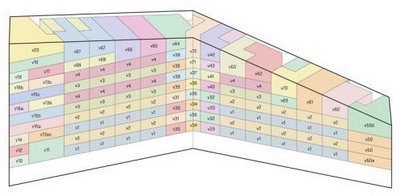

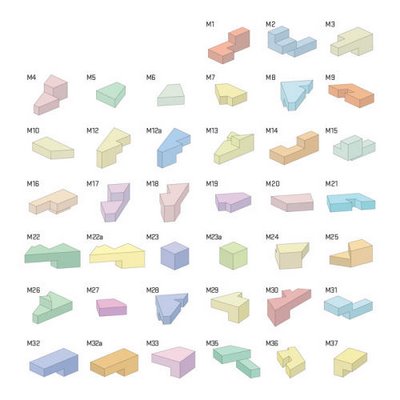

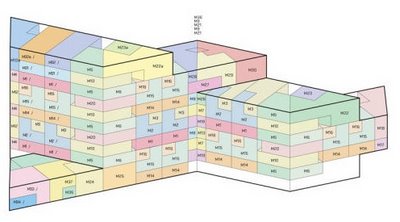

A new block of flats on the edge of Copenhagen, designed by Bjarke Ingels and Julien De Smedt of PLOT, was toured, analyzed, and photographically documented in last month's issue of Metropolis. The article is by Tom Vanderbilt, a writer whose career I find well worth following. (Here's his book). The article will tell you a lot more about the project than this brief and hurried post will – but, basically, the building is like a huge game of architectural Tetris, with a bewildering variety of interlinked floorplans. Specifically, there are "76 floor plans in 221 units," Vanderbilt writes, "with none repeated more than a dozen times and well over a dozen of them unique." Further, he says, "flipping through the sales booklet, which has pages of unit plans, is like reading the assembly blueprints for some massive urban machine with interlocking component parts." So what does it look like? First, here are some 3D shape-diagrams for the "V block" of the building; they almost look like proteins – enzymes of European domesticity.   Below is the "M block."   As Vanderbilt explains, the "V" and the "M" building shapes only entered into the design process after the architects "experimented with any number of permutations, the totality of which – collected on a display board – looks like some strange alphabet. They eventually settled on fashioning the south-facing block into a V and the north-facing block into an M. 'By bending the shapes,' Ingels says, 'you open up the maximum toward the two canals, which ensures that the apartments, instead of just looking at one another, all have orientation toward the landscape.' It also ensures that both evening and morning sun can enter the courtyard. The move shatters what would be a dense rectilinearity into a kind of crystalline parallax-view refraction of light and circulation." The whole complex was also finished with very tastefully bold, solid neo-Modernist colors. These eye-popping central corridors will, at the very least, wake you up every morning as you stumble out the door for work.    Finally, a note to property developers: "all 221 units sold out in three weeks, 80 percent on the first day." Good design pays. Read more in Metropolis.

|

|