Science Fiction and the City: Film Fest Update!

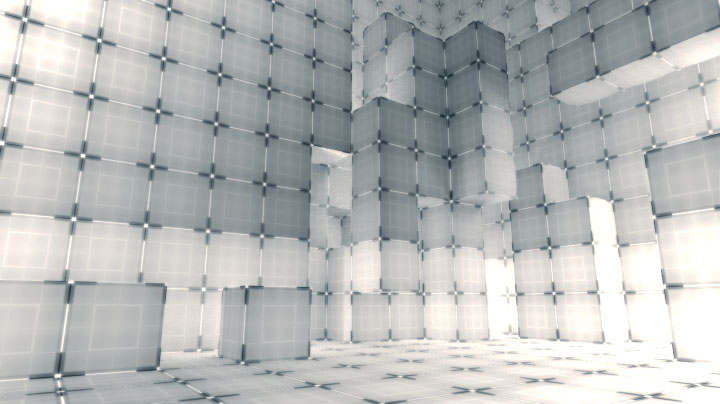

[Image: Ben Procter].

[Image: Ben Procter].A few weeks ago I announced that BLDGBLOG and Materials & Applications had teamed up to curate an architectural film fest as part of this year's Silver Lake Film Festival here in LA.

Well, I have some exciting news to announce: on Tuesday, May 8th, from 8-10pm, inside a converted wind tunnel in Pasadena, we'll be hosting an evening full of talks and presentations about film, science fiction, space, landscape, and architecture.

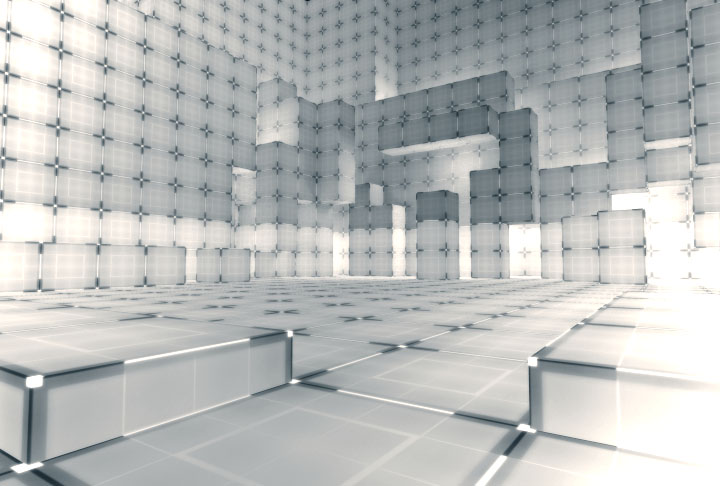

[Image: James Clyne].

[Image: James Clyne].I have said many times before on this blog that contemporary architecture could learn quite a lot from the spatial and material imaginations on display in both film and science fiction – so perhaps this event will be a good opportunity to explore what that really means.

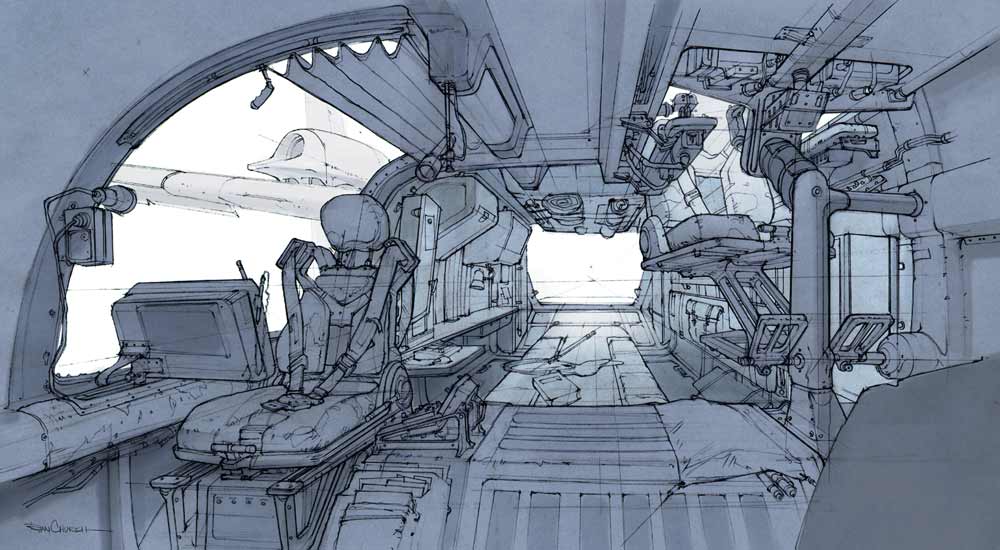

[Image: Ryan Church].

[Image: Ryan Church].Though the connections between film and architecture run too deep – and are either too widely known or too conceptually entangled – to discuss in full here, I still think it's worth pointing out, briefly, a few examples of cinematic thinking in architecture. Or architectural thinking in cinema, as it were.

One of the greatest essays on Piranesi ever written, for instance, was produced by Russian film director Sergei Eisenstein – whose father, interestingly, was an architect.

While studying Piranesi's notoriously vertiginous etchings of imaginary prisons, Eisenstein felt moved to write an essay about the basic cinematic acts of montage and cutting. If Piranesi's prisons are anything, Eisenstein suggests, they are spaces edited together from unrelated episodes; they are cinematic.

He calls them "architectural frenzies."

Inspired by this realization, Eisenstein goes on to say that even film should be reconsidered, on a structural level, as "a sequence of collisions," a "succession of broken links," thousands and thousands of different frames and spaces that then unite into a coherent whole. The individual stills of a film sequence – like the individual rooms of a building – thus fuse into an "ecstatic construction."

[Image: Ryan Church].

[Image: Ryan Church].Less abstractly, Jonathan Glancey claims, in an old article for The Guardian, that "cinema remains the best place to experience the architectural imagination at full flight."

Through film, Glancey writes, an audience can get "highly wrought glimpses into future cities; for popular audiences, such films offer thrilling guides as to how our world might look." He continues:

- What is fascinating, and very much an area for further research, is the close relationship between radical architectural design and the cinema. Much of the best of modern architecture, combining digital and three-dimensional design processes, is cinematic in scope and feeling.

- If only the members of Archigram or Superstudio had been able to buy, in the 1960s, the kind of cheap digital technology available on high streets today. They may not have been able to get their dream cities constructed, but they could have visualised them in mini-movies – much more enticing than so many drawings, lectures and models.

It's also interesting, though, in this context, to point out the work of M. Christine Boyer, and her excellent book The City of Collective Memory.

There, Boyer writes about Edward Gordon Craig, an early 20th-century stage set designer (and son of an architect), whose "architectonic scenery" foregrounded architectural backdrops, turning them into the only action an audience was meant to watch.

For instance, Craig "proposed that a stage in which walls and shapes rose up and opened out, unfolded or retreated in endless motion could become a performance without any actors," Boyer writes. "The stage thus became a device to receive the play of light rhythmically, creating an endless variety of mobile cubic shapes and varying spaces. Deep wells, stairs, open spaces, platforms, or partitions created a stage of complete mobility, which Craig believed appealed to the imagination."

The architecture does all the acting for you; the architecture is the film – or the play, as the case may be. The architecture is the storyline.

The space itself is the plot.

[Image: Ben Procter].

[Image: Ben Procter].So what does all this have to do with cinema and architecture – or even with science fiction and the city?

Well, by talking not to architects but instead to the people who actually design the sets, backdrops, cityscapes, environments, buildings, rooms, etc., in which cinematic action takes place – from X-Men 3 to Charlie and the Chocolate Factory – you should be able to get at least some sense for what architecture can mean, on a narrative level, to those outside the architectural field.

In other words, what do those people who tell stories through and with space actually want from architecture?

How do they use space?

Rather than set out to discover, yet again, what architects think about cinema – or about science fiction, or about stage set design – why not turn the question around? Why not see what architects can learn from spaces, buildings, and cities produced by other fields?

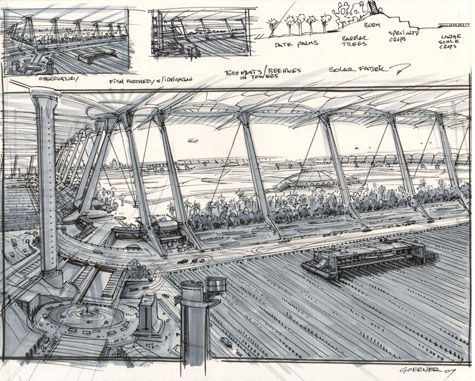

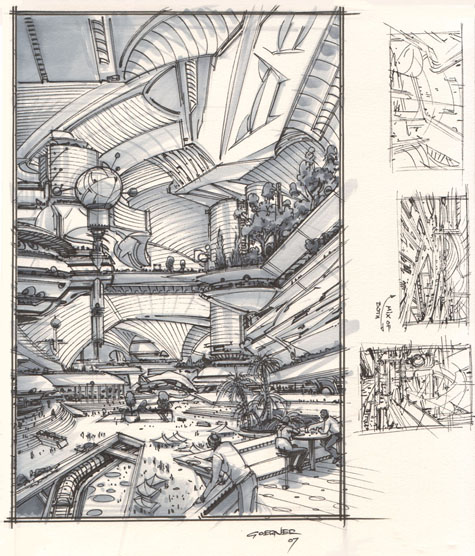

[Image: A sketch by Mark Goerner; here's a larger version].

[Image: A sketch by Mark Goerner; here's a larger version].Or, to ask another question that won't necessarily be answered by this event: if Architectural Record bills itself as a magazine about architecture, then why doesn't it ever cover, say, the apartment complex from Minority Report, or the office lobbies featured in The Matrix? That's architecture, too.

In any case, Materials & Applications and BLDGBLOG have therefore gathered together four of the most exciting concept artists working in film today to discuss some of these questions, and to talk about their own artistic backgrounds – how they got into film, what they studied to get there, and what imaginative role architecture plays in their creations.

They will each give a short, 15-20 minute talk, with images, and the whole thing will be followed by a Q&A. And, just to mention this again, because I love saying it, this will take place in a converted wind tunnel, formerly used for testing the aerodynamism of experimental vehicles.

But I'll be posting about the wind tunnel in a few days (complete with some really cool pictures).

[Image: Ben Procter].

[Image: Ben Procter].The resumes of these four guys, then, put together, cover so much cinematic ground that it's almost easier to name what they haven't worked on; nonetheless, here are the speakers – with an abbreviated list of their film production credits.

In alphabetical order, you'll see Ryan Church, James Clyne, Mark Goerner, and Ben Procter.

[Images: Ryan Church].

[Images: Ryan Church].Ryan Church has worked on The War of the Worlds, Star Wars II: Attack of the Clones, and Star Wars III: Revenge of the Sith – with stills from each film available on his site.

Some of the landscapes and structures that Ryan has produced are just extraordinary; there's this titan arch vs. these linked arches; there's this weird interior full of glowing discs; there's this thing; there's the Death Star under construction – etc. etc. etc.

Awesome work can be found all over this page, in fact, including some truly amazing sketches.

[Images: Three environments by Ryan Church; larger versions available here, here, and here].

[Images: Three environments by Ryan Church; larger versions available here, here, and here].Check out Ryan's bio for more.

Moving onward, alphabetically, we find James Clyne, who has worked on A.I. (check out this Caspar David Friedrich-esque landscape, in particular), Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (!), Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, Minority Report (including this cityscape and these freeways), Mission to Mars, The War of the Worlds, and X-Men 3, among others.

[Images: James Clyne].

[Images: James Clyne].There's then Mark Goerner, who's worked on Constantine, Minority Report, The Terminal, and X-Men 2 (including Magneto's plastic prison), among others. Check out this crashed ship-city, piercing the lunar surface, in both sketch and final versions.

[Image: Reef City by Mark Goerner].

[Image: Reef City by Mark Goerner].Of course, Mark has also designed a space station.

Ben Procter, finally, has worked on a bewildering number of films, including the forthcoming, feature-length version of The Transformers. His work also appears in Blade 2, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, The Matrix: Reloaded and The Matrix: Revolutions, Pirates of the Caribbean, The Ring, Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow, Superman Returns, and The Terminal, among others.

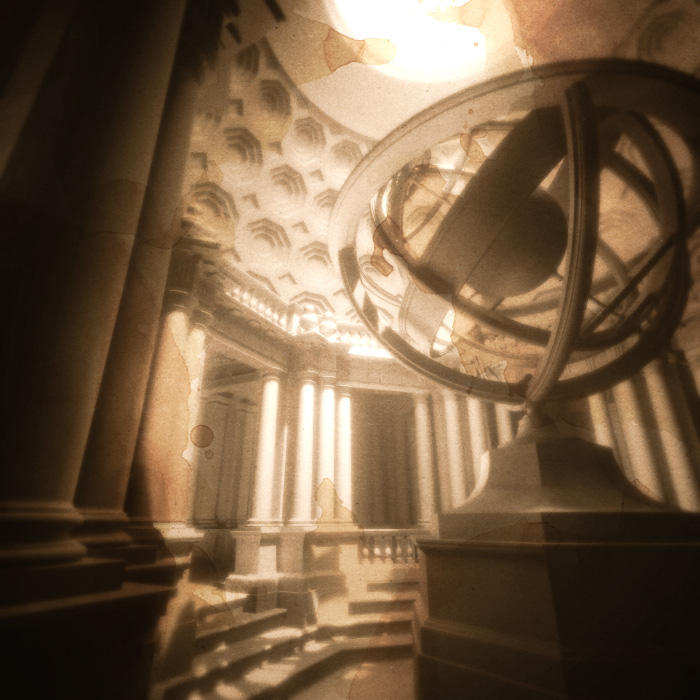

[Image: Ben Procter].

[Image: Ben Procter].Ben has produced environments for games such as Need for Speed: Underground, and he's even helped spatially conceptualize a few music videos for Mariah Carey, Ginuwine, and Busta Rhymes.

[Image: Ben Procter].

[Image: Ben Procter].His resume has more information (available as a PDF).

So come out if you can on May 8, 2007, from 8-10pm, at the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena. Hear about film, architecture, and science fiction; learn how these artists were educated and how they found the careers that they did; ask questions about artistic influences, strategies, and intentions; find out what it's like to work on a Steven Spielberg film; and see some more of their work, from film stills to sketchbooks to video clips.

The former wind tunnel, meanwhile, is absolutely enormous, so there's no need to worry about reservations or whether you'll be able to get in. And bring some extra cash, in case you want to purchase one of their instructional books or DVDs; they're cool guys and deserve the support. And I'll repost about all this once the event draws closer, complete with address, etc. etc., so don't worry if you read this post and don't know how to get there. The event is nearly two months away. Don't panic.

[Image: A sketch by Mark Goerner; here's a much larger version].

[Image: A sketch by Mark Goerner; here's a much larger version].Expect more soon...

Comments are moderated.

If it's not spam, it will appear here shortly!

Geoff, I'm consistently impressed by the breadth of your writing and the fascinating conjectures your both raise and cite.

I really wish I could attend this event.

Geoff,

Will there be any way to get hold of transcripts of the talks at this event? Being in the UK means I can't attend, but these are themes that fascinate me.

regards,

Jim Rossignol

Indeed, will a podcast or quicktime movie be available?

Your examples of imagery conjure up comparisons of Syd Meade, who's work I truly respect. You've inspired me to research further into each of these artists.

what a fascinating event!

this connection between cinema, science fiction, space, landscape, and architecture is producing a breathtaking results. i wonder if there will be a more specific reference to the relation between cartography and cinema as well?

and the imagery you have posted here is strikingly amazing, i hope there will be a possibility as well for see a pod cast of this gathering?

This sounds like one of the most interesting and intellectually stimulating evenings of the year -- I wish there was some way I could attend. Add my vote to those above who hope for a podcast or webcast or some other *cast.

My PhD thesis is "architecture, science fiction and comic books", i'm surprise by this thing...any suggest about authors?

Geoff,

I am really looking forward to this event, it sounds like it will be even better that the last one. I hope that you continue to curate such exciting events. I am so glad I am LA right now!

Hey Geoff,

Looking forward to the event. In the spirit of converted wind tunnels and adaptive reuse in general, I thought you might find this link interesting: It's about the history of Chicago's Public Library, which was first housed in a converted water tower after the Great Fire.

http://www.chipublib.org/digital/woop/woop_gallery.html

I think the work of the Blame! manga belongs with the images you posted.

Great stuff, although it always seems a shame when such invention gets reduced to being background glimpses in what are often mediocre movies. Let's hope some of these people get books of their work out.

And hi to Jim Rossignol, good to see you here. :)

Geoff,

Just found these:

http://features.cgsociety.org/story_custom.php?story_id=3987

Visuals inspired by Greg Bear's Eon.

Subterranean architecture isn't just futuristic, it's becoming mainstream. See SubsurfaceBuildings.com.

it's easy to say that these buildings prove "real" architects to be unimaginative and bland, but i bet none of these artists, when designing their futuristic megastructures, ever thought about where to put the toilets. this is what architects call "theoretical" work - it would look great in a sci-fi movie, but the real needs of civilization, and of individual human beings, is much simpler than these fantasy renderings would imply.

You say that, but one of the key instances of implemented sci-fi architecture is in videogames, and as all gamers know there is *always* a toilet. In fact 'Toilets In Games' has become the running joke feature concept in the UK gaming press.

-Jim Rossignol

At the very least, I think, the event will be recorded and transcribed - but if we can do a podcast, or a series of podcasts, then that sounds cool, too. And far less labor-intensive! I'll let you know.

But it shouldn't be a situation where, if you're not in LA, you're just out of luck. I'll hook you up...

Thanks for all the links, etc., meanwhile, especially Rob and Geist and max!

Geist, is that series any good? Or does it just sound really good? Have you seen it?

Well, this event should be really fun, so if you're around be sure to come by. And if you have any further questions, etc., just let me know - but, seriously, stop by if you're in LA that evening. It'll be fun, and I'd love the turn-out - and I know Ryan, James, Mark, and Ben all deserve the attention.

In addition to Jim's thought there, I simply don't think that "where to put the toilets" is the de facto proof of a good architect. A house could have the most wonderfully-located toilets in the world, and still be an awful place in which to live.

Also, I think the toilet comment misses the whole point here: I'm not saying that these are buildable designs, as is, straight from these sketches; I'm saying, instead, that people who work with space from outside the field of architecture are usually less encumbered with the expectations of architectural history (Mies, Loos, Le Corbusier) - and, thus, are often in a position to help architects imaginatively reconfront the built environment. Or confrontationally reimagine that environment.

I'm not saying, "These guys know more about architecture than real architects do"; I'm saying: "Why not see what non-architects think about architecture - especially if those non-architects design buildings all day?" And somewhere in the answer to that question will be an interesting conversation.

Geoff, Blame! is fantastic. The Manga that is, the film is rather bad, sadly.

I'm sure you can find the .cbr files on Got Lurk?

cheers

I wish i lived anywhere near California so that i could attend this event.

My take on architecture and cinema:

http://www.yume.co.uk/architectural-representations-of-the-city-in-science-fiction-cinema

Geoff,

This is by far your best post ever. For the first time, you've made me think beyond the average and inspired me to research more and actually write more. Great references and info here. Better than Glancey's original mediocre article. Thanks a lot. I only wish I could attend the event. More of this sort of stuff please!

Hi Geoff,

I am glad that someone finally wrote something about this! Keep the great work you are doing!

I would like to report that the links to the James Clyne section on this article are not correct. Could you change this?

Thank you!

Jawn

Thanks, Jawn - I think all the links are fixed now.

Hope to see you at the event -

Post a Comment