If these reefs are islands

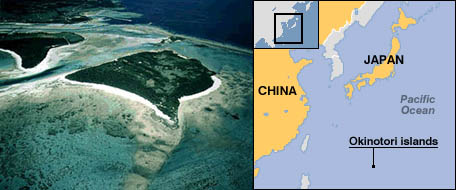

[Images: Japan's Okinotori Islands, via the BBC, next to an unrelated image of a different reef; all reef images used in this post are from different locations].

[Images: Japan's Okinotori Islands, via the BBC, next to an unrelated image of a different reef; all reef images used in this post are from different locations].The BBC recently revisited the story of why Japan is now growing coral reefs in a bid to extend their territorial sovereignty into the Philippine Sea.

Successfully transplanting and cultivating these reefs would, in theory, allow Japan "to protect an exclusive economic zone off its coast"—expanding Japanese maritime power more than 1,000 miles south of Tokyo.

- According to the Law of the Sea, Japan can lay exclusive claim to the natural resources 370km (230 miles) from its shores. So, if these outcrops are Japanese islands, the exclusive economic zone stretches far further from the coast of the main islands of Japan then it would do otherwise. To bolster Tokyo's claim, officials have posted a large metal address plaque on one of them making clear they are Japanese. They have also built a lighthouse nearby.

At the moment, the Okinotori Islands (as they're called) are merely "rocky outcrops"; but, by artificially enhancing their landmass through reefs—using reef "seeds" and "eggs"—Japan can create sovereign territory.

At the moment, the Okinotori Islands (as they're called) are merely "rocky outcrops"; but, by artificially enhancing their landmass through reefs—using reef "seeds" and "eggs"—Japan can create sovereign territory.This means that they'll win economic control over all the minerals, oil, fish, natural gas, etc. etc., located in the area—providing friendly sea routes for American military ships in the process.

The U.S., of course, thinks that Japan's sovereign reefs are a great idea; China, unsurprisingly, thinks the whole thing sucks.

In fact, we read:

- Chinese interest in Okinotori lies in its location: along the route U.S. warships would likely take from bases in Guam in the event of a confrontation over Taiwan. China's efforts to map the sea bottom, apparently so its submarines could intercept U.S. aircraft carriers in a crisis, have drawn sharp protests from Japan that China is violating its EEZ.

A tiny bit more information about all this is available at the Times.

So the rest of this story could go in any number of directions:

So the rest of this story could go in any number of directions: 1) A speculative survey of other "rocky outcrops" and manmade reefs, to see who might be able to claim them and why. For instance, if Japan's reef-based territorial ambitions are successful, could this establish a legal precedent for other such experimental terrains?

Or perhaps it could mean that the U.S. will turn away from Treasury-depleting global military adventurism to spend money on more interesting projects within its own borders—funding a whole new series of Hawaiian islands, designed by Thom Mayne, that would extend Hawaii archipelagically toward Asia...

Greece, inspired, would then expand the Cyclades with a cluster of designer islands, slowly growing to dominate the Mediterranean once again—a kind of inverse-Odyssey in which the islands themselves do all the traveling...

Or maybe there'll be a whole new terrestrial future in store for Scotland's Outer Hebrides, or for the Isle of Man, or for Friesland—or perhaps even a whole new Nova Scotia, extending hundreds of nautical miles into the waters of the north Atlantic, a distant, fog-shrouded world of melancholic introspection, visited by poets...

2) It's worth remembering that the possession of land and territory has not always been a recognized marker of political sovereignty—so the Earth, in the sense of geophysical terrain, is here being swept up into a model of human governance that has only existed for a few hundred years, and which may only exist for a few decades more. So, under a different political system, these artificial reefs would be quite literally meaningless.

3) The generation of new territory for the purpose of extending—or consolidating—political power is nothing new. As but one example, I happen to be reading The Conquest of Nature: Water, Landscape, and the Making of Modern Germany, a book that "tells the story of how Germans transformed their landscape over the last 250 years by reclaiming marsh and fen, draining moors, straightening rivers, and building dams in the high valleys."

The relevance of this here, in the context of artificial Japanese reefs in the south Pacific, is that Frederick the Great used hydrological reclamation projects—i.e. marsh draining and river redirection—literally to create new territory; this expanded the political reach of Prussia by generating more Earth upon which German-speaking settlers could then build farms and villages. All in all, this was a process of both "agricultural improvement and internal colonization," and it "increasingly assumed the character of a military operation."

As David Blackbourn, the book's author, further notes: "External conquests created additional territory on which to make internal conquests, spaces on the map out of which new land could be made." Indeed: "For Prussia, a state that was expanding through military conquest across the swampy North European plain, borders and reclamation went together."

4) Finally, last week New Scientist ran a whole bunch of little articles called "The last place on Earth..." In each case, that leading phrase was followed by a subheading, such as: "...to be discovered," or "...where no explorer has set foot."

Another of those articles was: "...to be unclaimed by any nation."

As the magazine comments in that piece: "States will go to great lengths to secure territorial claims over what appear to be worthless pieces of land." After all, "owning even a remote rock can significantly extend a nation's access to marine resources such as oil and fish."

But those "great lengths" to which the nations of tomorrow may someday go could include the outright geo-architectural construction of whole new landmasses, islands, and offshore microcontinents. These terrains will be governed by Kurtzian technocrats, with iron fists, whose unchecked cruelty will inspire the literary classics of the 22nd century...

In any case, all of these points seem to imply that architects may need to brush up on their marine geotechnical skills—as well as on the legal issues surrounding the archipelagic future of political sovereignty.

Comments are moderated.

If it's not spam, it will appear here shortly!

I can't wait for the new literature this may inspire, since the concept of created landforms was one of the more interesting motifs in Neal Stephenson's The Diamond Age.

Exactly the same as what Singapore does. They still expanding their land through reclamation and refuse to talk about teritorial border untill now. Maybe not until their landmass touch the land of Indonesia, their neighbour-country. The funny thing is, the (sea)sand which they use for reclamation is imported from Indonesia. And many small islands have sunk because of this.

I think you remember China did same thing at Spratly Islands.

Correclty, they build construnction on reefs that are under water.

Ha, I wanted to mention the Singapore connection as well. At least according to some of the literature I read for a paper on it, most of Singapore's mountains were flattened out in a sand-mining process to get money for land expansion.

Because the government is not so big on transparency and freedom of science, there are still no studies on the way this may have affected the tides in... erm, I think it's the Malaysian Straits?

Also, apparently all of their neighbors have quit selling them sand, recognizing how damaging the product could be to their own sovereignty at sea.

as an interesting counterpoint to this, I remember reading an article about an episode in which the Australian government attempted to give away a number of small islands in the pacific, as they were having trouble guarding them against illegal immigrants. Under Australian law, they automatically became refugees the minute they touched australian soil, and Howard's position on the issue of refugees is well known. I'm fascinted by the ingeniousness of governments when it comes to circumventing their own laws and humanitarian safety mechanisms. I wonder if somewhere there's an Patent Office for Geopolitical Inventions...

For many years I've said I want to build up a reef in international waters, name it as a sovereign nation, put a hut on it, declare war on the United States and the collect international relief funds to build it even bigger.

I do seriously wonder about the possibility of building an island in international waters though. Could you declare it a new country or would it automatically belong to the country in which you are a citizen?

No one mentioned Surtsey, that volcanic island in Iceland. Iceland is very big on enforcing its maritime rights, and it has the cod, unlike everyone else, to show it. When Surtsey rose from the sea, they were able to extend their rights, but now the island has been sinking, and there is some discussion of building it up to keep it from vanishing.

Flounder Lee asked about the possibility of building his own nation island. That discussion generally gets around to "you and what army" at some point or another.

Okay, that's really scary.

Why? Because I can easily see China poisoning the reefs to stop this process. And with that country's blatant disregard for the health of ... well, anybody or anything, really... the results could be staggering.

Fascinating post, as usual...

The Dutch have built a whole new province called Flevoland in the last 50 years and have built two large cities on it since - one - Almere, is still growing with a new center based on designs by Rem Koolhaas. They built the province by draining part of the Zuyder Zee, but they have the know-how to build new land anywhere in the world. They were called in to help build the new Palm Islands out there in the Persian Gulf too. Building a new land entirely out in the sea present physical and geo-political problems but perhaps the Japanese technique really can work to create new land. The Dutch methods so far have been in shallow waters near existing landmasses. The libertarian grandson of Milton Friedman -- Patri Friedman, wants to build new territory far from the grasp of imperial powers though, with his Seasteading proposals. He's the most serious of such types I've come across, and could very well eventually pull it off.

Tony Skaggs (Project Alphistia)

Post a Comment