Liberation Hydrology: Miami, 2107 A.D.

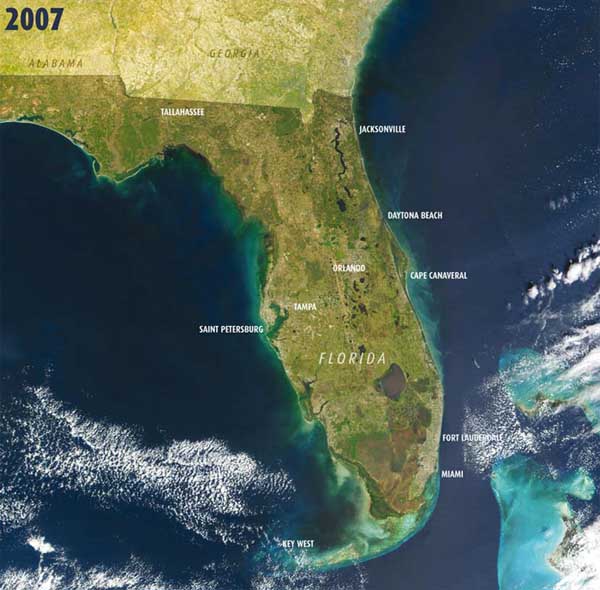

[Image: Florida in 2007; via New Scientist].

[Image: Florida in 2007; via New Scientist].In a subscriber-only article over at New Scientist, NASA climate scientist James Hansen describes what the planet might look like after a "runaway collapse" of the West Antarctic ice sheet.

The collapse, or melting, of the sheet, of course, would be caused by increased global temperatures – temperatures altered by the atmospherically unique quantity of carbon dioxide that's now floating around up there. That carbon dioxide has been released by human industrial processes.

"There is not a sufficiently widespread appreciation of the implications of putting back into the air a large fraction of the carbon stored in the ground over epochs of geologic time," Hansen writes.

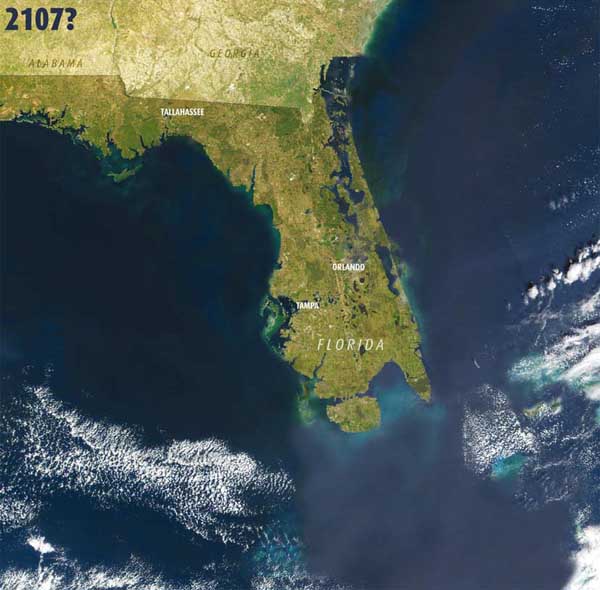

[Image: Florida in 2107; via New Scientist].

[Image: Florida in 2107; via New Scientist].In any case, the article points out that this future sea-level rise will actually increase over time, as the melting of the ice sheet itself accelerates.

- As an example, let us say that ice sheet melting adds 1 centimetre to sea level for the decade 2005 to 2015, and that this doubles each decade until the West Antarctic ice sheet is largely depleted. This would yield a rise in sea level of more than 5 metres by 2095.

From the article:

- Without mega-engineering projects to protect them, a 5-metre rise would inundate large parts of many cities – including New York, London, Sydney, Vancouver, Mumbai and Tokyo – and leave surrounding areas vulnerable to storm surges. In Florida, Louisiana, the Netherlands, Bangladesh and elsewhere, whole regions and cities may vanish. China's economic powerhouse, Shanghai, has an average elevation of just 4 metres.

However, the main problem I have with using maps and scenarios like this to get people worked up about climate change is that these warnings often seem to have the opposite effect.

In other words, these things are actually so evocative, and so imaginatively stimulating, that it's hard not to get at least a tiny thrill at the idea that you might get to see these things happen.

Nothing against Miami, but all of south Florida under several meters of water? With Cape Canaveral lost under a subtropical lagoon and St. Petersburg an archipelago?

The problem, it seems, is that climate change scientists, in describing these unearthly terrestrial reorganizations, are science fictionalizing, so to speak, our everyday existence. The implicit, if inadvertant, message here seems to be: hey, south Floridians, and all you who are bored of the world today, sick of all the parking lots and the 7-11s, tired of watching Cops, tired of applying to colleges you don't really want to go to, tired of credit card debt and bad marriages, don't worry.

This will all be underwater soon.

It could be called liberation hydrology.

Climate change becomes an adventure – the becoming-science-fiction of everyday life.

[Image: Northwestern Europe in 2107; via New Scientist].

[Image: Northwestern Europe in 2107; via New Scientist].It seems no wonder, then, that the more apocalyptic these scenarios get, the more we find the same blasé reaction: oh, you mean Manhattan will be underwater? In 100 years?

I think the way to get people truly concerned about climate change – if fear-mongering is, in fact, the correct strategy to use here (after all, if you don't like fear-mongering in the War on Terror, then why should you apply the same tactics to climate change?) – is not by talking about unprecedented and spectacular transformations of the Earth's surface. New archipelagos! Forests in Antarctica!

Drowned cities!

Instead, it would seem, you have to point out quality of life issues: you might starve to death, for instance, as organized agriculture and food distribution chains are interrupted. Malnourished, your teeth will fall out and your hair will grow thin. You may be living in a refugee camp, with neither privacy nor close friends nor personal safety. The governments of the world may have collapsed, overwhelmed by the logistical burden of displaced populations and by the loss of the world's economic centers, like NY, London, and Shanghai; there will thus be no police; you might be physically assaulted on a regular basis. There will be rats, roaches, and rivers of human sewage – followed closely by disease, infection, infant mortality, and premature death. And you won't just be able to drive away, leaving the catastrophe behind – because the roads will be potholed, without a government to fix them, and your car will probably have been stolen, anyway. Clean water will be a luxury; you'll be drinking radiator water out of abandoned pick-up trucks, rusting on the sides of highways outside St. Louis.

In any case, my point is just that the more outlandish and imaginatively evocative your predictions get, describing some new, fantasy geography of rising sea-levels and tropical lagoons – a whole new Earth, coming your way soon – the more people will actually want to see that happen. Of course, the same thing is no doubt true for what I just wrote, above, in describing the apocalypse: after all, there are many people who will actually want to experience that – unpoliced refugee camps included.

Still, showing maps of an unrecognizable future world doesn't scare people; it taps into their explorer instinct – new lands, terra incognita.

And it gives people some truly awesome scenarios to think about – like scuba-diving through the submerged remains of Cape Canaveral, or rediscovering Amsterdam, a city lost to the silt and seaweed.

If this is what people think climate change will bring them, then a whole lot of people are probably looking forward to it.

Comments are moderated.

If it's not spam, it will appear here shortly!

Clever argument, Geoff... As a culture, we definitely do have a strange obsession with fear and disaster. It's a good explanation for widespread apathy: we won't do anything unless there's a reason for concern, and when there's a reason for concern we're not in a hurry to return to the boredom of tranquility.

However, I have a hard time getting scared about the "even worse" scenario you describe. We've proven that we can deal (not necessarily well) with sudden environmental disasters like massive hurricanes without governments collapsing and society falling into shambles. Surely we can organize a proper response to the slowly rising sea level.

The logistics are not going to be worked out by themselves, but I don't think we're going to wake up one day with millions of surprised, displaced people.

So it sounds like more fear-mongering to me, indeed. Which is fine if you're okay with that...

Sam - I agree that the scenario I describe in the post, above, is a kind of fear-mongering - but that's why I mention fear-mongering in the post.

My point is simply that climate change narratives, as they now stand, can run the risk of captivating people - and so, if you really want to convince people of the coming horrors, then you need to change your rhetorical and/or descriptive strategy. Otherwise you make the future, with its slowly rising sea-levels, sound like an adventure.

As far as whether the world will actually descend into an anarchic assemblage of refugee camps... I don't think it's accurate for you to compare the displacement of at least 1/10th of the Earth's population to something like a "massive hurricane."

If we have to abandon Miami, Los Angeles, Mumbai, London, Tokyo, Sydney, Melbourne, Shanghai, New York City, parts of San Francisco, Rio de Janeiro, Cairo, Barcelona, the Greek islands, Houston, etc. etc. etc., simultaneously and in a period of 100 years, then that will cause social, political, and economic upheaval the likes of which the modern world has never seen. Will governments survive that? Let alone central air-conditioning, advanced medicine, the housing market, and urban sanitation? I would do it quite highly.

But that's if anything of the sort ever happens. And, even then, such a scenario may not inspire people to action: it'll just be like living through a science fiction movie - they'll just pack an extra battery for their cameras and take lots of photographs.

Anyway, I don't think you can underestimate the impact of a massive sea-level rise - you're right that it won't be a sudden thing (you won't "wake up one day with millions of surprised, displaced people"), but even if it takes 200 years, imagine reorganizing the entirety of planetary life away from coastal developments and established cities, shifting hundreds upon hundreds of millions people inland.

I don't think modern society would survive that task.

* that should say "I would doubt it quite highly" (not "do it")

But where do all these places get their supplies from? The power, water, food, etc. all come from inland, sometimes very far inland. The coastal developments (at least in the US), if anything, are a drain on the resources of the inland folks. How much of New York State's fresh water is used by New York City alone?

The fact is that these cities are dependent on an infrastructure that is rooted on quite solid ground, even if the cities themselves aren't. The shifting population is a problem, sure, because there are a hell of a lot of people in those cities. But you've got a century to figure that out.

Not that we shouldn't fight global warming, mind you; but turnips in Kansas (and nuke plants in Arizona) are not going to suddenly stop growing (glowing?) if Los Angeles slides into the ocean.

The perfect follow-up to the London post. The idea of scuba diving in the submerged, coral-spiked catacombs of St. Paul's was a pretty enticing advertisement for rising sea levels. The entire travel industry just licked its proverbial lips. Missing teeth, societal collapse, radiator water, and having to live near Saint Louis, however...not so exciting.

I think that, perhaps, the true horror of the displacement described would probably be a direct result of the slow encroachment of the coastline: what we see as horrific would be the new normalcy. Severe change like this, extended over a long period of time (100 years, say) would undermine society by creating indifference to extreme suffering. As conditions worsen, people tend to get better and better at looking the other way. Governments, air conditioning, advanced medicine...these would all survive, but they'd probably serve fewer and fewer people.

Refugee camps would likely be the de facto form of urban development (if you can call it that)...what would be most interesting to see would be how the central cores of inland cities like Chicago, Denver, Toronto, Vienna, Moscow, Bogota, et. al. would respond to these massive tidal waves of people at the same time that they start dealing with hurricanes, typhoons, and other disasters that they weren't built to withstand. *That* could be where governmental collapse comes in.

Of course, our generation has seen entire cities built virtually from scratch in a matter of years (Dubai, Shenzhen) so who knows...maybe, with 100 years to react, inland cities will be able to plan for the influx. It'll be a wild ride either way...

I think your argument is compelling. I do wonder, though, if the mappings are necessarily exciting to people, or if they are just unrealistic. It's one thing to go around and show pictures of floods from so many miles away from the Earth and scream, "apocalypse!" It's quite another to understand the meaning of a flood, like you said, and relating it to how people's lives are affected rather than geography.

But showing mappings seems distant to people. I really don't think people are so much excited (maybe I am slightly less cynical than you!) but more so that they don't realize the significance of floods. People who've never lived through a flood don't understand them. People on higher ground won't care enough, because not only is the map so distant, it is not even of their part of the world.

Perhaps images showing submerged houses and stores and cars (entire lives destroyed), but applied to other areas, would do the trick. Why would people in Denver care about a flood? Maybe they would if they saw their own city flooded.

I do agree with Brenda, though - the ability of people today to create a city from thin air is remarkable. Coastal (and just inland) civilization is going to get pretty interesting.

Geoff,

Very interesting and appropriate take... the secular 'second coming' myth. Maybe we should start listening to the military, they are the only branch of government taking the threats seriously.

Army Times (read the report)

http://www.armytimes.com/news/2007/04/military_global_warming_070416/

But I think when people are faced with such real and potentially catastrophic consequences it makes people apathetic. To tell you the truth I do not see much of a difference between a sea level rise map or a scene of a future dystopia. They are both overwhelming and seem so larger than life that would make me stop paying attention.

I guess the scare tactics are necessary to get people to pay attention, but for them to do something about it you need to put power in their hands. We need to be given clear paths and ways to reverse it, if not we will just not care. So we need to develop a clear narrative that includes winning to go along with the negative narrative. We should narrate a green future of innovation and progress.

sam, Dr. Hansen has said that the sea level rise may not be so slow. He compares it to defreezing your fridge. At first a couple of drops fall, but then BAM! the whole sheet breaks down. We may not have so much time to adapt.

I suppose, to a certain extent, that I'm one of the people you talk about being excite. I see maps like that and instinctively wonder what those new coasts will look like, what the cities will look like after they adapt.

Problem, of course, being the adapting part. Tom Barnett has made the good point in his blog (www.thomaspmbarnett.com) that a lot of the impact of global warming will depend on the wealth of the nations involved. Here in the US, we have many options. We can retrofit tall buildings to be habitable when partially submerged, and build new buildings with submersion in mind. As the economies of the beach towns fade, their populace can drift inland in much the same way as the rust belt dwellers drifted south and west (ironically, said rust belt offers plenty of empty space for putting refugees). Heck, I've been seeing grand schemes for floating cities for over a decade now! Other parts of the first world can also recover.

But the poorer regions of the world won't be so fortunate. They don't have many tall buildings, and can't afford to build more. Their floating cities, if any, would look like something out of WATERWORLD. Their inland cities would see their slums swollen by refugees, and if environmental changes collapsed their agriculture. . .

Oh God, the rising water is just part of the problem. More problematic is creeping desertification that will match the rising water with browning green coming from the other direction.

One problem we're already seeing is the intelligent and aware becoming bored with this story. Global warming is so last year.

By the way, LA is not going under, except for some parts of Malibu and Venice. San Francisco (ahem) on the other hand . . .

I think the 1st problem with global warming is exactly that... global.

As a species, I'm not aware of us having ever faced something on a planetary scale before. We're so used to dealing in the local ie: tribal wars, national interests, border disputes etc.

I think we face a problem in first overcoming our pitiful senses of nationality identity, which only breed territorial possessiveness and linguistic insularity.

How can the planet be helped unless we're working together?

However, as stated many places before, maybe the short cut through all that frayed tape is corporations. They transcend borders quicker than you can say "copyright glaciers...? mmm... interesting idea..." and when it comes to worldwide pollution, they unsurprisingly account for a much higher rate, than the average "you-me-yeah-i-do-my-best"

Perhaps, the argument becomes more persuasive when "da bling" is what's up... yr lifestyle, yr threads, yr hoildays, even yr job! all potential fatalities unless this issue is addressed...

but then again, will corporations only be interested in helping, if they can see a powerpoint map with their flag firmly implanted at the top of the revolving graph?

but corporations can only work if people are there, and people are only there if they have air to breath.

so, maybe it's time to climb down from the trees and start planting them...

In response to the first comment from Sam:

Is our fascination with disaster really that strange? Seeing the systems that deceptively enable us come to an end, or at least forcibly altered by drastic environmental change makes me giddy. Not for the unpoliced refugee camps or solar radiation poisoning, but for karmic correctness of it, for the inevitable end to our hubris.

Monocle Magazine's latest naming the 20 most livable cities made me laugh. It is one of the most arrogant, oblivious features I have ever seen (or maybe I'm just more aware of these things now). Granted the magazine is published in the UK, but not one of the cities mentioned was in the Americas, Africa, or Asia. Apart from Tokyo, every city was inhabited by predominately Anglo Europeans. This is a completely inaccurate depiction of the future of the world's cities. These ethnic bubbles will be destroyed, and livable will be a thing only the ultra-elite can afford (most of Monocle's cities are like that already).

Honolulu, Montreal, Vancouver, Tokyo, Singapore, and Kyoto moved to Europe and/or Australia? Wow, I didn't realize.

Part of the problem with getting people concerned is with the time-scale."2107- Oh, I will be dead about fifty years then!" I think forty years into the future is about as far as most people can project.

I wonder how many more years of it not warming we have to have before the anthropogenic global warming hypothesis gets a critical examination?

Fear sells and controls.

Michael.

I really liked your point regarding the entertainment possibilities of global warming cataclysm because my first reaction to idea of all these areas going under was:

"Anarchist Surf Paradise...Awesome!"

yeah...death...disaster..etcetera, but I'd be just as happy living out of my WonderWagon and beaching everyday as I am pursuing a career and all the shite that it entails.

before the anthropogenic global warming hypothesis gets a critical examination

Michael, I believe that the "critical examination" of anthropogenic global warming is going on now in a lab near you, and it's called science.

And I have to go further with Brendan's thoughts here about the new issue of Monocle. Not only is it simply not true - and this takes little more than a quick flip through the magazine to realize - that "none" of the cities in that issue are in the Americas or Asia (though, yep, there are none in Africa), but I'm also led to ask what cities your alternative list might include, Settlement Heart? Is Lagos one of the world's most liveable cities? Or Cartagena? How about Cape Town? Shenzhen? Or maybe Calcutta? What's your list?

Is your problem with the word "liveable" – i.e. Mumbai is perfectly "liveable" to the people who actually live in Mumbai – or is it with the fact that Monocle considers a city "liveable" only if it's comfortable, safe, well-designed, and economically advantageous for its residents?

You say that Monocle's list is "a completely inaccurate depiction of the future of the world's cities" – but that's not the point of the issue. Monocle is also a terrible guide to radio astronomy - luckily it never claimed to be such a thing.

Anyway, I'd agree with you (if this is what you're saying) that "liveable" could also apply to a fecally contaminated slum somewhere outside Rio, but I have a feeling that this was not the type of poetic analysis that Monocle's editorial staff was hoping to perform.

Finally, as far as calling nearly a billion people an "ethnic bubble" (all billion of us "Anglo Europeans"), I appreciate the warning: I'll be sure to watch out for you and your racially-motivated soldiers when you show up in my town, hoping for my destruction in advance simply because of my ethnicity or skin color.

I'm curious: are you also eagerly awaiting the day when other "ethnic bubbles," like the Kurds of northern Iraq, or the Roma of Europe, or those nasty little Tibetans standing before the warriors of imperial China, are wiped out by your predicted city of the future?

How obnoxious is it to be part of an "ethnic bubble"!

And as far as your total dismissal of the European urban model goes - i.e. high taxation/high amenity - referring to it as something only the ultra-elite can afford, you are totally wrong about the socio-economic reality of what it takes to live in cities like Munich, Paris, Barcelona, etc.

But they're just an ethnic bubble, so fuck them, right?

Holy crap. I had typed out a similar response, originally...but I self-censored because I didn't want to start a flame war or any such business.

Bravo.

I think my response was a little over the top, actually - apologies for that.

I still mean everything I said; I just would have said it differently. Apologies for the tone of my comment - it's rather confrontational - but I do mean everything it says.

You have managed to terrify me as to the effect of underwater cities. It's true, when you look at a map of what will be under water, you don't get that sense of terror.

Well done.

Geoff Manaugh wrote:

Michael, I believe that the "critical examination" of anthropogenic global warming is going on now in a lab near you, and it's called science.

And said lab indicates that anthropogenic global warming, as in enhanced greenhouse effect, can firstly be considered refuted due to the mismatch in fingerprinting between the predicted and actual atmospheric warming profile. And secondly, by the temperature responses on forcing not showing negative feedback characteristics, falsifying the alleged effect of positive feedbacks.

That's it, projections and predictions false. Hypothesis falsified. Popper philosophy end of story.

Michael ... who notes that GMT has not risen since 1998 - nearly a decade.

There's a point that seems to be implicit in Geoff's account that he's not stressing -- that I don't see anyone explicitly noting -- and that's the speed that's implicit in the catastrophic narratives.

It's the implied speed of the thing that makes it seem like 'an adventure'. Without that, it's just a slow grind down toward missing teeth and drinking from slimy puddles. Because in the real climate-apocalypse scenarios, this is all going to happen over six or seven decades, not just a few short years.

It will take a lifetime, in short, for things to get really bad. A long, slow, grinding lifetime.

It's not Day After Tomorrow; it's not even a climate-change version of Atlas Shrugged. A really honest narrative scenario might be more like a sort of inverse version of Wild Strawberries, as a protagonist struggles through a lifetime of watching the world go to hell, and dies knowing that it's got farther yet to fall.

Post a Comment