|

|

We just had another earthquake. The house jolted; the front door chain swung back and forth, tapping the doorframe; and I stood up, looking out the back window, realizing that if all hell breaks loose I'm really thirsty and I don't have any bottled water. The jolting became a dull vibration, and then it ended. I sat back down on the futon. It was a 5.6 on the Richter scale, and the epicenter was 5.7 miles beneath the Earth's surface. It was Event 40204628. Earlier: Event 14312160

[Image: By and via Energie in Motion]. [Image: By and via Energie in Motion].This morning's post reminded me of a link someone sent in two weeks ago: Energie in Motion, a light-writing project by two guys in Germany. Hey, little man! What are you doing outside by yourself? You look sad.  [Image: By and via Energie in Motion]. [Image: By and via Energie in Motion].There's no need to hide!  [Image: By and via Energie in Motion]. [Image: By and via Energie in Motion].It's just me... For more images, stop by the Energie in Motion site itself. There's even a short video you can watch of the men at work, writing with light in Munich and Hamburg, turning parking meters into robots and animating street signs with little glowing arms and legs. It'd be interesting, meanwhile, if you could install some sort of moving light sculpture in the center of the city. The sculpture appears to be totally abstract: casually and randomly, it switches back and forth amongst various positions, spinning little lights around, making arcs, circles, hops, jumps, and flashes, all to no real purpose or design – but then someone accidentally takes a photo of it using too long an exposure... The resulting images, developed back at home in a basement darkoom, reveal that the sculpture is actually writing things in space. Like this:  [Image: By and via Energie in Motion]. [Image: By and via Energie in Motion].It just requires an elongated present moment in which to read it. Turns out it's a new way for spies to communicate – and this random tourist with a camera has now uncovered a sinister plot... Alfred Hitchcock directs the film version. (Thanks, Joel D.! Vaguely related: Automotive Ossuary).

[Image: White Noise/White Light, Athens, by Höweler + Yoon/MY Studio]. [Image: White Noise/White Light, Athens, by Höweler + Yoon/MY Studio]. I stumbled on an old project from the summer of 2004 today, by Höweler + Yoon/ MY Studio, called White Noise/White Light. The project was on display in Athens during the 2004 Olympics: Comprised of a 50' x 50' grid of fiber optics and speakers, "White Noise/White Light" is an interactive sound and light field that responds to the movement of people as they walk through it... As pedestrians enter into the fiber optic field their presence and movement are traced by each stalk unit, transmitting white light from LEDs and white noise from speakers below. And though I wasn't in Athens to see the thing in person, it certainly did photograph well.  [Image: White Noise/White Light, Athens, by Höweler + Yoon/MY Studio]. [Image: White Noise/White Light, Athens, by Höweler + Yoon/MY Studio]. Juxtaposed with the Parthenon in the background, the effect, in fact, looks quite mesmerizing. Electrical practicalities and issues of light pollution aside, it'd be nice to install something like this for a few nights along the rim of the entire Grand Canyon... Then fly over it in a glider, at 3am, taking photographs. UPDATE: How strange: I came home from work today to find two copies of Architect magazine waiting for me in the doorway – and lo! On p. 49 of their September 2007 issue there's nothing else but "White Noise/White Light" by Höweler + Yoon... Architect says: "The experience and publicity that Höweler + Yoon gained from the Olympics project have led to new commissions and further explorations in up-to-the-nanosecond lighting technologies." Interesting overlap. (Earlier: Archidose blogged it).

Flying into Vegas last night to speak at a conference hosted somewhere inside the Venetian Hotel by the Urban Land Institute, I read Cormac McCarthy's recent novel, The Road. It's a book I'd long wanted to read but kept putting off for some reason, and I'm glad I finally read it.  [Image: By Trevor Manternach, found during a Flickr search]. [Image: By Trevor Manternach, found during a Flickr search].If you don't know the book, the basic gist is that the United States – and, we infer, everything else in the world – has been annihilated in what sounds like nuclear war. But all of that is just background for the real meat of the book. The Road follows a father and son as they walk south, starving, toward an unidentified coast. They cross mountains and prairies and forests; everything is burned, turned to ash, or obliterated. The father is coughing up blood and the skies are permanently grey. Briefly, I'd be interested to hear, out of sheer curiosity, where other people think the book is "set" – because it sounds, at times, like the hills of New York state or even western Massachusetts; at other times it sounds like Missouri, Tennessee, parts of Mississippi, and the Gulf Coast; at other times like the Sierra Nevadas, hiking down toward the rocky shorelines just north of, say, Santa Barbara. Sometimes it sounds like Oregon. In any case, the only glimpse we get of the war itself is this – and all spelling and punctuation in these quotations is McCarthy's own: The clocks stopped at 1:17. A long shear of light and then a series of low concussions. He got up and went to the window. What is it? she said. He didnt answer. He went into the bathroom and threw the lightswitch but the power was already gone. A dull rose glow in the windowglass. He dropped to one knee and raised the lever to stop the tub and the turned on both taps as far as they would go. She was standing in the doorway in her nightwear, clutching the jamb, cradling her belly in one hand. What is it? she said. What is happening?

I dont know.

Why are you taking a bath?

I'm not. After this, the landscape outside is described as "scabbed" and "cauterized," heavily covered in ash. McCarthy memorably writes: "They sat at the window and ate in their robes by candlelight a midnight supper and watched distant cities burn." The wife soon gone – indeed, she's only ever present through flashbacks – the father and son stumble south pushing their food supplies, a few toys, and some "stinking robes and blankets" in an old grocery cart. They come across Texas Chainsaw Massacre-like houses, as some bands of bearded survivors have taken to cannibalism. Interestingly, every house seems vaguely terrifying to the young boy in a way that the dead forests and dried riverbeds simply do not. Empty houses on hills with their doors left open. So their journey down the road continues: By then all stores of food had given out and murder was everywhere upon the land. The world soon to be largely populated by men who would eat your children in front of your eyes and the cities themselves held by cores of blackened looters who tunneled among the ruins and crawled from the rubble white of tooth and eye carrying charred and anonymous tins of food in nylon nets like shoppers in the commissaries of hell. (...) Out on the roads the pilgrims sank down and fell over and died and the bleak and shrouded earth went trundling past the sun and returned again as trackless and as unremarked as the path of any nameless sisterworld in the ancient dark beyond. And then they approach what appears to have been a place actually struck by those distant concussions of sound and light, the perhaps atomic bombs of an unexplained war: Beyond a crossroads in that wilderness they began to come upon the possessions of travelers abandoned in the road years ago. Boxes and bags. Everything melted and black. Old plastic suitcases curled shapeless in the heat. Here and there the imprint of things wrested out of the tar by scavengers. A mile on and they began to come upon the dead. Figures half mired in the blacktop, clutching themselves, mouths howling. He put his hand on the boy's shoulder. Take my hand, he said. I dont think you should see this. It's a good book. It's not perfect; a friend of mine quipped that it ends with "a failure of nerve," and yet the nostalgic tone of the book's final paragraph suited me just fine. Which just leaves us, readers of things like this, preparing in whatever small ways we can to survive some undefined possible apocalypse of our own time here, the future politicized, the reservoirs drying, the religions hording arms and the oceans full of plastic. It'll be interesting to see what happens next. Cormac McCarthy: The Road

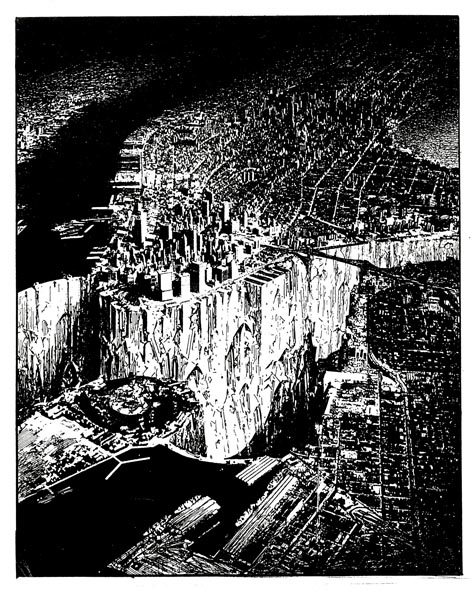

With drought on my mind, it was interesting to come across two new articles in The New York Times today, both about the United States of waterlessness. The less interesting of the two tells us that "[w]ater levels in the Great Lakes are falling; Lake Ontario, for example, is about seven inches below where it was a year ago" – and, "for every inch of water that the lakes lose, the ships that ferry bulk materials across them must lighten their loads... or risk running aground."  [Image: The Great Lakes are draining; photo by James Rajotte for The New York Times]. [Image: The Great Lakes are draining; photo by James Rajotte for The New York Times].What's causing this? "Most environmental researchers," we read, "say that low precipitation, mild winters and high evaporation, due largely to a lack of heavy ice covers to shield cold lake waters from the warmer air above, are depleting the lakes." I'm reminded of something Alex Trevi sent me several weeks ago, in which writer and comedian Garrison Keillor speculates as to what might happen if the state of Minnesota sold all the water in Lake Superior. Keillor describes a fantastical project called Excelsior, in which the Governor of Minnesota "will stand on a platform in Duluth and pull a golden lanyard, opening the gates of the Superior Diversion Canal, a concrete waterway the size of the Suez. Water from Lake Superior will flood into the canal at a rate of 50 billion gal. per hour and go south." It will flow into the St. Croix River, to the Mississippi, south to an aqueduct at Keokuk, Iowa, and from there west to the Colorado River and into the Grand Canyon and many other southwestern canyons, filling them up to the rims – enough water to supply the parched Southwest from Los Angeles to Santa Fe for more than 50 years. The drained landscape left behind will be renamed the Superior Canyon – and the Superior Canyon, Keillor says, will put the Grand Canyon to shame. "It's bigger, for one thing," he writes, "plus it has islands and sites of famous shipwrecks. You'll have a monorail tour of the sites with crumpled hulls of ships. Very respectful." By 2006, Keillor speculated (he was writing from the Hootie & the Blowfish-filled year of 1995): Lake Superior will be gone, and its islands will be wooded buttes rising above the fertile coulees of the basin. A river will run through it, the Riviera River, and great glittering casinos like the Corn Palace, the Voyageur, the Big Kawishiwi, the Tamarack Sands, the Clair de Loon, the Sileaux, the Garage Mahal, the Glacial Sands, the Temple of Denture, the Golden Mukooda will lie across the basin like diamonds in a dish. Family-style casinos, with theme parks and sensational water rides on the rivers cascading over the north rim, plus high-rise hotels and time-share condominiums. Currently there are no building restrictions in Lake Superior; developers will be free to create high-rises in the shape of grain elevators, casinos shaped like casserole dishes, accordions, automatic washers. Celebrities will flock to the canyon. You'll see guys on the Letterman show who, when Dave asks, "Where you going next month, pal?" will say, "I'll be in Minnesota, Dave, playing four weeks at the Pokegama." Tourism will jump 1,000%. Guys on the red-eye from L.A. to New York will look out and see a blaze of light off the left wing and ask the flight attendant, "What's that?" And she'll say, "Minnesota, of course." All of which actually reminds of Lebbeus Woods, and his vision of a drained Manhattan.  [Image: Lebbeus Woods, Lower Manhattan; view larger]. [Image: Lebbeus Woods, Lower Manhattan; view larger].But perhaps such a willfully fictive reference overlooks the reality of the drought(s) now creeping up on the United States. In a massive new article published this weekend in The New York Times, we're given a long and rather alarming look at the lack of water in the American west, focusing on the decline of the Colorado River. A catastrophic reduction in the flow of the Colorado River – which mostly consists of snowmelt from the Rocky Mountains – has always served as a kind of thought experiment for water engineers, a risk situation from the outer edge of their practical imaginations. Some 30 million people depend on that water. A greatly reduced river would wreak chaos in seven states: Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada and California. An almost unfathomable legal morass might well result, with farmers suing the federal government; cities suing cities; states suing states; Indian nations suing state officials; and foreign nations (by treaty, Mexico has a small claim on the river) bringing international law to bear on the United States government. And it will happen; this "unfathomable" situation will someday occur. The American West will run out of water.  [Image: Simon Norfolk, a photographer previously interviewed by BLDGBLOG, taken for The New York Times]. [Image: Simon Norfolk, a photographer previously interviewed by BLDGBLOG, taken for The New York Times].Or will it? At one point in his genuinely brilliant book Cadillac Desert, Marc Reisner describes something called N.A.W.A.P.A.: the North American Water and Power Alliance. N.A.W.A.P.A. is nothing less than the gonzo hydrological fantasy project of a particular group of U.S. water engineers. N.A.W.A.P.A., Reisner tells us, would "solve at one stroke all the West's problems with water" – but it would also take "a $6-trillion economy" to pay for it, and "it might require taking Canada by force." He quips that British Columbia "is to water what Russia is to land," and so N.A.W.A.P.A., if realized, would tap those unexploited natural waterways and bring them down south to fill the cups of Uncle Sam. Canadians, we read, "have viewed all of this with a mixture of horror, amusement, and avarice" – but what exactly is "all of this"? Reisner: Visualize, then, a series of towering dams in the deep river canyons of British Columbia – dams that are 800, 1,500, even 1,700 feet high. Visualize reservoirs backing up behind them for hundreds of miles – reservoirs among which Lake Mead would be merely regulation-size. Visualize the flow of the Susitna River, the Copper, the Tanana, and the upper Yukon running in reverse, pushed through the Saint Elias Mountains by million-horsepower pumps, then dumped into nature's second-largest natural reservoir, the Rocky Mountain Trench. Humbled only by the Great Rift Valley of Africa, the trench would serve as the continent's hydrologic switching yard, storing 400 million acre-feet of water in a reservoir 500 miles long. And that's barely half the project! The project would ultimately make "the Mojave Desert green," we read, diverting Canada's fresh water south to the faucets of greater Los Angeles – thus destroying almost every salmon fishery between Anchorage and Vancouver, and even "rais[ing] the level of all five [Great Lakes]," in the process. After all, N.A.W.A.P.A. also means that the Great Lakes would be connected to the center of the North American continent by something called the Canadian–Great Lakes Waterway. But N.A.W.A.P.A. is an old plan; it's been gathering dust since the 1980s. No one now is seriously considering building it. It's literally history.  But who knows – perhaps 2008 is the year N.A.W.A.P.A. makes a comeback. Or, perhaps, in January 2010, after another dry winter, Los Angeles voters will start to get thirsty. Perhaps some well-positioned Senators, in 2011, might even start making phonecalls north. Perhaps, in 2012, some recent graduates from water management programs at state-funded universities in Illinois or Utah might catch the itch of moral rebellion; they might then start redrawing their personal maps of the continent, going to bed at night with visions of massive dams in their heads, writing position papers for peer-reviewed hydrological engineering magazines. Perhaps, in 2017, ten years from now, BLDGBLOG – if it's still around – will even be reporting from the rims of these gigantic structures, thrown up overnight in the remote and untrafficked darkness of riverine western Canada. Long, perfectly calibrated concrete sluices and pumps will bring water thousands of miles south through redwood forests to the open basins of California's reservoirs, and photographs of their incomprehensibly expensive and exactly poured geometry will elicit whistles of embarrassed awe from readers on the streets of Weehawken.  [Image: A fish-cleaning station in Las Vegas Bay, now abandoned by the West's sinking waters; taken by Simon Norfolk for The New York Times]. [Image: A fish-cleaning station in Las Vegas Bay, now abandoned by the West's sinking waters; taken by Simon Norfolk for The New York Times].Or perhaps it won't be N.A.W.A.P.A. after all, but some titanic new project identical in all but name. Will California wait for the coming drought to destroy it – or will the state take drastic measures?

Just a quick note that I'll be speaking in Las Vegas on Wednesday afternoon, October 24, as part of the Urban Land Institute's 2007 annual meeting.

I'll be on a panel with Christopher Hawthorne, architecture critic for the L.A. Times; Neil Takemoto of CoolTown Studios; and Ted Bardacke of Global Green.

So if you're in Las Vegas – though you have to register for the conference – be sure to stop by.

Wildly, it's also the day to catch Queen Noor of Jordan; she has a B.A. in Architecture and Urban Planning from Princeton – and, who knows, maybe she's a dedicated reader of BLDGBLOG (I'm not holding my breath).

[Image: Lake Lanier, Atlanta's primary source of drinking water, gets lower and lower; photo by Pouya Dianat for The Atlanta Journal-Constitution]. [Image: Lake Lanier, Atlanta's primary source of drinking water, gets lower and lower; photo by Pouya Dianat for The Atlanta Journal-Constitution].Via Pruned, we read that Atlanta may have less than four months of water left, that the governor of North Carolina has asked his constituents "to stop using water for any purpose 'not essential to public health and safety,'” and that an ongoing, 18-month drought, complete with "cloudless blue skies and high temperatures," has "shriveled crops and bronzed lawns from North Carolina to Alabama." So is this the new desert southeast, a grassless landscape of abandoned golf courses, college dorms left empty amidst the remains of dying pine forests, and the sand dunes of Kitty Hawk creeping in toward Raleigh-Durham? And could Atlanta really run out of water before March 2008?

First, a general note: as some of you may know, I'm in the process of turning BLDGBLOG into a book for Chronicle Books. That's due out in Spring 2009. Accordingly, over the next three or four months, until the manuscript is due, I'll be cutting back a bit on posting, going down to maybe two or three times a week... But that's only till February! After which I'll have a bright, new book waiting to be designed by the wizards at Chronicle. So keep coming back – but be aware that I won't be posting everyday. And buy a copy of the book!Second, I haven't done a Quick List in a long time, so I thought I'd take a casual swing through some recent stories...  [Image: Zoe Crosher's new pamphlet, published by the LA Forum]. [Image: Zoe Crosher's new pamphlet, published by the LA Forum].In other bookworld news, for instance, the LA Forum has just put out a new pamphlet, featuring photographs of Los Angeles International Airport taken by artist Zoe Crosher. But the images have a catch: all of the photos were taken inside airport hotel rooms. Zoe Crosher takes the viewer on an exploratory journey inside the impersonal and transient travel world surrounding the mega international airport, LAX. She finds a landscape packed with identical hotel chains pushed up against giant billboards, where the words "hotel" and "taxi" are understood by nearly everyone. (...) The pattern[s] of the drapes change, the color of the stucco exterior changes and the airplanes caught in mid flight move through the atmosphere, but the basic view stays the same. There is a haunting familiarity that one has never really left the first room... Read more at the LA Forum. In other book news, readers of BLDGBLOG's recent 2-part interview with Mary Beard may be pleased to hear that Beard's Wonders of the World series just got one book bigger. Keith Miller's St. Peter's just arrived at my house this afternoon.    [Images: (top) A wonderful – stunning! – photo of Rome, with the dome of St. Peter's catching sunlight in the background, by George O. Goodman; (middle) A view inside St. Peter's nested domes and arches by Andrew Huxtable; (bottom) St. Peter's Square, photographed by mambo1935]. [Images: (top) A wonderful – stunning! – photo of Rome, with the dome of St. Peter's catching sunlight in the background, by George O. Goodman; (middle) A view inside St. Peter's nested domes and arches by Andrew Huxtable; (bottom) St. Peter's Square, photographed by mambo1935].Speaking of architectural history, an " underground monastery dating back to the 17th century has been restored in West Russia's Belgorod region. The huge underground complex, which was looted and destroyed after the October Revolution, was sanctified again by the local Archbishop." The combined length of the caves is over 650 meters, and they resemble a real labyrinth. But the central part looks like any Orthodox Christian church and there are passages around the site for religious processions. The monastery is dry and temperatures inside remain stable year round at about 6 degrees Celsius. Two wonderful details: 1) At its height, the monastery apparently had "no less than 1,000 meters of underground galleries and tunnels that lead to churches on the surface." 2) "During the Revolution, the monks had abandoned the complex and for some time the caves were populated by anarchist gangs." I believe this is the same place – and if you like this kind of thing then don't miss BLDGBLOG's look at the allure of the underground city. Moving in the opposite vertical direction, 33 Thomas Street, in New York City, is a windowless concrete high-rise built solely for the purpose of housing a telephone exchange.  [Image: 33 Thomas Street, via Wikipedia; view slightly bigger]. [Image: 33 Thomas Street, via Wikipedia; view slightly bigger].According to Wikipedia, 33 Thomas Street "is a telephone exchange or wire center building which contains three major 4ESS switches used for interexchange (long distance) telephony, two owned by AT&T and one owned by Verizon." Further, "As it was built to house telephone switching equipment, the average floor height is 18 feet (5.5 meters), considerably taller than in an average high-rise. The floors are also unusually strong, designed to carry 200 to 300 pound per square foot (10 - 15 kPa) live loads." Really a gigantic pseudo-Brutalist vault, the building is probably crawling with government wire-tappers – its windowless walls and concrete geometry the subject of at least half a dozen occult urban myths. For instance, the ghost of Aleister Crowley is said to live there, sitting cross-legged in "a mass of blue and violet plumes," performing divine telegraphy, sending messages into the ether, " crowned with the stars of night."  [Image: The fires of chromosomal mutation burn]. [Image: The fires of chromosomal mutation burn].Then there was some news about artificial life: "Craig Venter, the controversial DNA researcher involved in the race to decipher the human genetic code, has built a synthetic chromosome out of laboratory chemicals and is poised to announce the creation of the first new artificial life form on Earth." The Guardian refers to this as "a giant leap forward in the development of designer genomes." All of which is certainly interesting in and of itself, but what might this news herald for the future of landscape architecture? Could someone genetically engineer entire gardens and flowering species, new trees, shrubs, and lichen? Let's ask Brazil, where the New York Times reports that "sprawling labs and experimental fields" run by the government have been making "Brazil's savannah bloom." We learn that most of these sprawling labs' "pioneering work" has been performed "in the cerrado, the vast savannah that stretches for more than 1,000 miles across central Brazil. Written off as useless for centuries, the region has been transformed in less than a generation into Brazil’s grain belt, thanks to the discovery that soils could be made fertile by dousing them with phosphorus and lime" – chemically conjuring fertility from the ground.   [Images: The future of the Brazilian Earth, photographed by Lalo de Almeida for New York Times]. [Images: The future of the Brazilian Earth, photographed by Lalo de Almeida for New York Times].But making the Earth more fertile is sometimes just a matter of better harvesting techniques: Pruned introduced us last month to a new breed of picking machines that may soon be set loose upon the American agricultural landscape, harvesting fruits with an efficiency human hands can't quite – apparently – achieve. But what might happen if these future machines get hacked? What strange new incisions in the landscape might result? Or, "[e]ven more interesting," Pruned asks, "what will happen if they become self-aware and go out to pasture? Fitted with solar panels, grazing from one oil well to another, domiciling in abandoned gold mines, what new ecologies will they terraform?" This becomes, yes, even more interesting when you add another article – also discovered via Pruned – about the strategic use of crops as a form of pharmaceutical cultivation: Conventional ways to make modern medicines are expensive, which means pharmaceutical companies generally target those diseases that affect lots of people who can pay. Plants can be grown, harvested, and the useful medicine purified from them at a fraction of the price, so using them as leafy drug factories saves a fortune, and opens the doors to treating people in poorer countries. Advocates say just 250 acres of GM potato crop could churn out enough hepatitis B vaccine to protect the entire population of south-east Asia from the disease for a year. Whole fields of genetically-modified medicine waving in the summer breeze: someday, perhaps, pills will grow on trees. But this scientized approach to the public health of tomorrow is not without its controversies. Later in that same article we read that one medically-augmented strain of tobacco is now being cultivated on "a Kent farm, in ultra-secure greenhouses with twin-skin plastic walls strong enough to resist a hurled brick." These ultra-secure greenhouses "are the botanic equivalent of the containment facilities used by microbiologists to work on biological weapons." In other words, the current legal climate surrounding these Hippocratic organisms means that they will be "swaying only in an artificial, heavily filtered breeze" for some years to come. So much for my visions of the pharmaceutical future... Until the harvesting machines show up.  [Images: Libya's ambitious plan is announced; via the BBC]. [Images: Libya's ambitious plan is announced; via the BBC].Further afield, it was announced last month that British architect Norman Foster will be designing a new " eco-region" for Libya – whether they want him to or not... For that project, Foster + Partners have drawn up "regional plans to create a national park, a renewable energy infrastructure, a public transportation infrastructure fuelled by biofuels, sustainable agriculture irrigated through desalination plants, and an eco-tourism resort. The latter could, according to some preliminary plans, have buildings built into the side of mountains to minimise their visual impact and take advantage of the stone's insulating properties." As the Guardian points out, the project's brief "basically says everything the world would want to hear: sustainable development; archaeological conservation; eco-tourism; renewable energy; environmentally responsible town planning; micro-banking; education; biofuels; even production of 'the finest quality organic food and drink'." Further: Foster's plan strives to avoid turning the coastline into another Benidorm. Nothing will be built along the seafront; all will be pushed back to the foot of the hills. Controlled zones of forest and agriculture will rise up the hills inland, towards the ruins on the plateau above. New towns will be based on the traditional Arab medina model: close-knit communities to minimise car use and urban sprawl. It would also be the near-perfect setting for a future J.G. Ballard novel. Just today, then, the New York Times jumps in, calling Foster's eco-region "a carbon neutral green-development zone, catering to tourism and serving as a model for environmentally friendly design," complete with "luxury hotels, villas and golf courses, as well as community housing." Sounds green, indeed! I'll fly there in my private jet and recycle Pepsi cans. Lots of Pepsi cans.  [Image: A rendering of the Libyan eco-region, ©Foster + Partners, via the New York Times]. [Image: A rendering of the Libyan eco-region, ©Foster + Partners, via the New York Times].Moving outward, then, New Scientist asks: "Did ancient oceans on Venus last long enough for potential life to have emerged? The answer could be locked inside a hardy mineral called tremolite, which future robotic missions to our neighbouring planet could find and study." After all, the "surface of Venus today is extremely dry and hot enough to melt lead," but at some point in the distant past it may have harbored seaborne life. Perhaps Norman Foster can build a resort there.  [Image: A Venusian mountain called Maat Mons; via New Scientist]. [Image: A Venusian mountain called Maat Mons; via New Scientist].However, if Venus doesn't interest you there are always " Super-Earths" – "rocky planets up to 10 times the mass of Earth." 10 times! Imagine the canyons, and the mountains, and the caves! Because of those planets' mass, we read, plate tectonics are apparently "inevitable." Further: "Plate tectonics may boost biodiversity by recycling chemicals and minerals through the crust. 'When it comes to habitability, super-Earths are our best destination,'" we're told – and "life" is just geochemistry in a slightly more mobile form. We're just pieces of the Earth's surface. But if there are Super-Earths, why not Super-Cities? Hong Kong wants to remind everyone that it's still a World-Class Destination®, and so it might – just might – merge with Shenzhen. The BBC explains that a new research report is recommending that "Hong Kong should be merged with Shenzhen, the southern Chinese city across the border, to make a mega-city of 20 million people. Only then can Hong Kong be one of the world's great cities."  [Image: The Hong Kong-Shenzhen Super-City as mapped by the BBC]. [Image: The Hong Kong-Shenzhen Super-City as mapped by the BBC].Fascinatingly, these plans for extended urban territoriality actually have to do with hydrology. Quoting at length: Back when Hong Kong was a British colony, its border with China was marked by the Shenzhen River, and like many rivers, it curved.

When the river was straightened, it left a square kilometre of land, technically owned by China and now under Hong Kong rule, known as the Lok Ma Chau Loop.

"Hong Kong and Shenzhen have been arguing about this, who should do what, so we're suggesting, in this place here, the land-right belongs to Shenzhen, but the administrative rights are Hong Kong's," [one of the aforementioned report's authors] said.

"So if we could use this as an example, as a pilot, Shenzhen people could just go there without visas, Hong Kong people could just go there, and let the market decide. Maybe this is a very good place for health care... for high-tech factories... for museums and whatever. This could be an example where the mainland and Hong Kong actually work together, borderless." And so on. I have at least ten more articles lined up for inclusion here, but I'll have to leave it at that. More soon. (Earlier on BLDGBLOG: Quick list 9, Quick list 8, etc. etc., and thanks to Alex Trevi for the Russian cave monastery link).

McSweeney's McSweeney's and the Park Life Store will be hosting a conversation between BLDGBLOG and Pulitzer Prize-nominated author Lawrence Weschler on Tuesday, October 16, here in San Francisco – at 220 Clement Street (aka the Park Life Store), starting at 7pm – to celebrate the paperback launch of Weschler's Everything That Rises: A Book of Convergences. Here's a map. Expect free wine, no entry fee, missing lakes, salt mines, and loads of inappropriate Hitler references. It'll be fun.

I got back from Los Angeles last night and my head is still spinning. I'd move there again in a heartbeat.

There are three great cities in the United States: there's Los Angeles, Chicago, and New York – in that order.

I love Boston; I even love Denver; I like Miami; I think Washington DC is habitable; but Los Angeles is Los Angeles. You can't compare it to Paris, or to London, or to Rome, or to Shanghai. You can interestingly contrast it to those cities, sure, and Los Angeles even comes out lacking; but Los Angeles is still Los Angeles.

[Image: L.A., as photographed by Marshall Astor]. [Image: L.A., as photographed by Marshall Astor].

No matter what you do in L.A., your behavior is appropriate for the city. Los Angeles has no assumed correct mode of use. You can have fake breasts and drive a Ford Mustang – or you can grow a beard, weigh 300 pounds, and read Christian science fiction novels. Either way, you're fine: that's just how it works. You can watch Cops all day or you can be a porn star or you can be a Caltech physicist. You can listen to Carcass – or you can listen to Pat Robertson. Or both.

L.A. is the apocalypse: it's you and a bunch of parking lots. No one's going to save you; no one's looking out for you. It's the only city I know where that's the explicit premise of living there – that's the deal you make when you move to L.A.

The city, ironically, is emotionally authentic.

It says: no one loves you; you're the least important person in the room; get over it.

What matters is what you do there.

[Image: An extraordinary photograph, called 4.366 Braille, by jenlund70]. [Image: An extraordinary photograph, called 4.366 Braille, by jenlund70].

And maybe that means renting Hot Fuzz and eating too many pretzels; or maybe that means driving a Prius out to Malibu and surfing with Daryl Hannah as a means of protesting something; or maybe that means buying everything Fredric Jameson has ever written and even underlining significant passages as you visit the Westin Bonaventura. Maybe that just means getting into skateboarding, or into E!, or into Zen, Kabbalah, and Christian mysticism; or maybe you'll plunge yourself into gin-fueled all night Frank Sinatra marathons – or you'll lift weights and check email every two minutes on your Blackberry and watch old Bruce Willis films.

Who cares?

Literally no one cares, is the answer. No one cares. You're alone in the world.

L.A. is explicit about that.

If you can't handle a huge landscape made entirely from concrete, interspersed with 24-hour drugstores stocked with medications you don't need, then don't move there.

It's you and a bunch of parking lots.

You'll see Al Pacino in a traffic jam, wearing a stocking cap; you'll see Cameron Diaz in the check-out line at Whole Foods, giggling through a mask of reptilian skin; you'll see Harry Shearer buying bulk shrimp.

The whole thing is ridiculous. It's the most ridiculous city in the world – but everyone who lives there knows that. No one thinks that L.A. "works," or that it's well-designed, or that it's perfectly functional, or even that it makes sense to have put it there in the first place; they just think it's interesting. And they have fun there.

And the huge irony is that Southern California is where you can actually do what you want to do; you can just relax and be ridiculous. In L.A. you don't have to be embarrassed by yourself. You're not driven into a state of endless, vaguely militarized self-justification by your xenophobic neighbors.

You've got a surgically pinched, thin Michael Jackson nose? You've got a goatee and a trucker hat? You've got a million-dollar job and a Bentley? You've got to be at work at the local doughnut shop before 6am? Or maybe you've got 16 kids and an addiction to Yoo-Hoo – who cares?

It doesn't matter.

Los Angeles is where you confront the objective fact that you mean nothing; the desert, the ocean, the tectonic plates, the clear skies, the sun itself, the Hollywood Walk of Fame – even the parking lots: everything there somehow precedes you, even new construction sites, and it's bigger than you and more abstract than you and indifferent to you. You don't matter. You're free.

[Image: Two beautiful photos by Andrew Johnson; here's the left, here's the right]. [Image: Two beautiful photos by Andrew Johnson; here's the left, here's the right].

In Los Angeles you can be standing next to another human being but you may as well be standing next to a geological formation. Whatever that thing is, it doesn't care about you. And you don't care about it. Get over it. You're alone in the world. Do something interesting.

Do what you actually want to do – even if that means reading P.D. James or getting your nails done or re-oiling car parts in your backyard.

Because no one cares.

In L.A. you can grow Fabio hair and go to the Arclight and not be embarrassed by yourself. Every mode of living is appropriate for L.A. You can do what you want.

And I don't just mean that Los Angeles is some friendly bastion of cultural diversity and so we should celebrate it on that level and be done with it; I mean that Los Angeles is the confrontation with the void. It is the void. It's the confrontation with astronomy through near-constant sunlight and the inhuman radiative cancers that result. It's the confrontation with geology through plate tectonics and buried oil, methane, gravel, tar, and whatever other weird deposits of unknown ancient remains are sitting around down there in the dry and fractured subsurface. It's a confrontation with the oceanic; with anonymity; with desert time; with endless parking lots.

And it doesn't need humanizing. Who cares if you can't identify with Los Angeles? It doesn't need to be made human. It's better than that.

In case anyone reading this happens to be in Los Angeles over the next few days, I'll be flying back to that city of individualized car geographies tomorrow to give a talk at UCLA's Hammer Museum alongside National Book Critics Circle Award-winning author Lawrence Weschler. We'll be celebrating the paperback reissue of Weschler's Everything That Rises: A Book of Convergences, published by McSweeney's. The event takes place Wednesday, October 10; it's free, open to the public, and it starts at 7pm. So, sure, it's just another event in a huge city somewhere in the 21st century, but I think it'll be a great time and I can't wait! Los Angeles! Lawrence Weschler! UCLA! It's free! If you need further convincing, just take a long look at Weschler's book about the Museum of Jurassic Technology, Mr. Wilson's Cabinet Of Wonder: Pronged Ants, Horned Humans, Mice on Toast, and Other Marvels of Jurassic Technology...

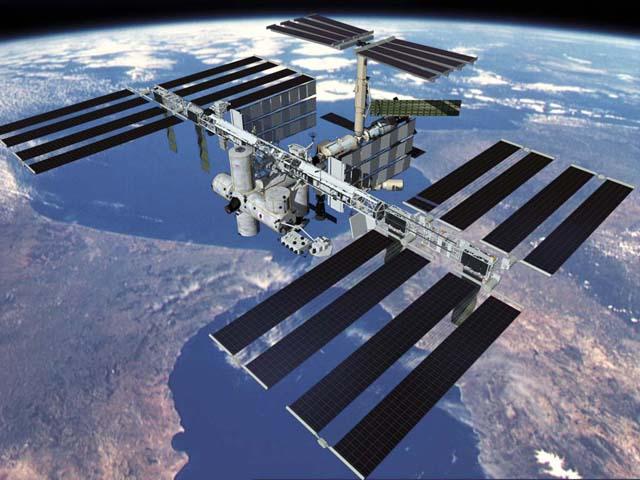

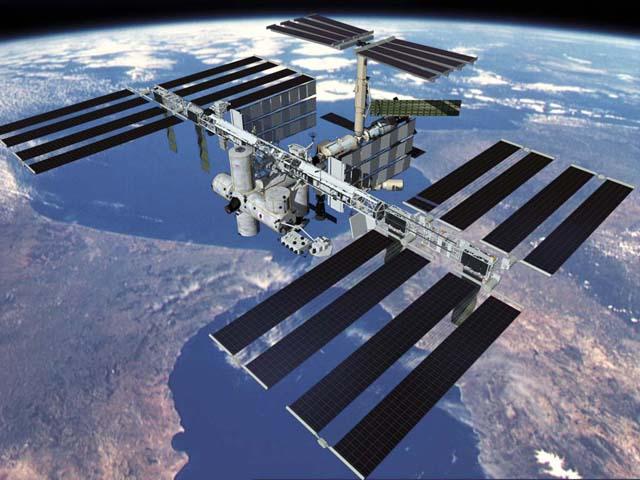

[Image: The International Space Station].Wired [Image: The International Space Station].Wired reports that "a swaggering Texas investor" wants to turn the International Space Station into a kind of orbiting drug lab – growing hi-tech medicines in space. After all, you can do "miraculous things" in microgravity: Disease-causing proteins crystallize so well – growing larger and clearer – that finding a drug to stop the protein's damaging activities could happen months, if not years, faster. In which case, putting architecture into space might have inadvertantly helped catalyze a cure for cancer.  [Image: A protein crystal – a kind of micro-ziggurat]. [Image: A protein crystal – a kind of micro-ziggurat].While it seems next to impossible to believe that we'll be able to maintain flights back and forth between Earth and the ISS in a post-oil economy, it is nonetheless quite fascinating to think that, someday, depressed teenagers in suburban Arizona might pop space-made anti-depressants, affecting hormonal moods through the use of literally extra-terrestrial substances; or musicians in small apartments in Prague might swallow attention deficit drugs crystallized in microgravity, writing the world's most intricate symphonies in response; or perhaps even illegal new hallucinogens will be developed in windowless, symmetrical rooms hovering 250 miles above the Earth's surface, and they'll be taken by Rem Koolhaas-reading students at SCI-Arc who then draw up plans for self-healing tentacular cities, under the influence of space...  [Image: Another protein crystal]. [Image: Another protein crystal].Either way, imagine that as your summer job! No longer connected to the surface of the Earth, wearing a hermetically sealed white suit, growing proteins. Read more @ Wired.

Being an enthusiast for all things astronomically observatory, I swooned last week when I read that "a growing number of Americans [have been] incorporating observatories into new or existing homes." Leading to the question: are suburban homes the new future of astronomy?  [Images: Michelle Litvin for The New York Times]. [Images: Michelle Litvin for The New York Times].According to the New York Times, "manufacturers of observatory domes report increasing sales to homeowners, and new residential communities are being developed with observatories as options in house plans." Most home observatories have between $10,000 and $40,000 in equipment, including telescopes, computers, refractors, filters and tracking mechanisms, according to astronomy equipment retailers. The total budget for an observatory can range from $50,000 to more than $500,000, depending on how technologically advanced the equipment and the size and complexity of the structure. As one home observatory-owning certified public accountant in Chicago told the newspaper: "Now, if I want to get up at 3 a.m. and look at something, I just open the shutter."  [Images: Erik Davies for The New York Times. On the right, we see a starburst cluster, courtesy of NASA]. [Images: Erik Davies for The New York Times. On the right, we see a starburst cluster, courtesy of NASA].Adding an astro-dome to your home requires some interesting architectural renovations, we read – mostly structural. For instance, each of these hi-tech telescopes requires "a dedicated foundation so it’s not subject to the vibrations transmitted by people walking around in the building," one manufacturer points out. "This usually involves elevating the instrument on a discrete concrete pier. A telescope mount is bolted to the pier and the mount is motorized so it rotates the telescope in sync with the dome." Concrete piers, home domes, private suburban observatories – I think it's the way forward. Imagine growing up in a planetarium! You'd go to sleep at night watching renamed constellations drift slowly over your bed.  [Image: Northern Cygnus as photographed by Robert Gendler]. [Image: Northern Cygnus as photographed by Robert Gendler].In fact, on a semi-related note, I've been wondering lately what might happen to Christianity – or to Islam, or to Hinduism – if it turned its houses of worship into observatories and planetaria: contemporary religious architecture as a physical participant in the planetary sciences. Your local church has a huge telescope installed above the altar, focusing on the rings of Saturn or on scenes of distant star birth; you take Communion while watching the moons of Jupiter. Or that mosque up the street is also a planetarium, hosting nightly shows about redshift and globular clusters. There are lines out the door and people reading Carl Sagan. Would that reinvigorate a failing religion? Your copy of the Koran comes complete with starcharts. The Book of Revelation gets rewritten, full of references to Bose-Einstein condensation and the inflationary universe. The Vatican itself installs the world's largest radio telescope inside a grove full of old stone statuary. As a joke, priests call it St. Radio – and, in a thousand years, the name sticks: children are brought up praying to this lost saint of astral frequencies. In any case, that wouldn't even be new in the history of religious architecture: as J.L. Heilbron points out in his book The Sun in the Church, some cathedrals were actually built – or at least later used, after minor alteration – as "heliometers": measuring labs for the passage of the sun. These "church observatories" were intially put to use, we read, in determining the most accurate date for Easter: The key parameter in the Easter calculation was the time of return of the sun to the same equinox. The most powerful way of measuring this cycle was to lay out a "merdian line" from south to north in a large dark building with a hole in its roof and observe how long the sun's noon image took to return to the same spot on the line. The most convenient such buildings were cathedrals; they came large and dark and needed only a hole in the roof and a rod in the floor to serve as solar observatories. Heilbron specifically mentions the Florentine church of Santa Maria Novella –  [Image: The Church of Santa Maria Novella, photographed by Flickr-user lorZ – that pillar standing in front is actually a gnomon]. [Image: The Church of Santa Maria Novella, photographed by Flickr-user lorZ – that pillar standing in front is actually a gnomon].– but there are at least a dozen other examples in the book. Heilbron also tells us about several "lost meridians" that were damaged – even utterly erased – by later building repairs; there was one such meridian inside the church of Saint Sulpice. But I can't get enough of this stuff! In fact, let's forget cathedrals and re-imagine secular urban infrastructure – parking lots and railways and police stations and sewers – as somehow astronomically integrated: the modern city as inhabitable heliometer, from its skyscrapers to its sidewalks. This almost reminds me of Lisa Jardine's discovery, while writing her biography of Sir Christopher Wren, that the so-called London Monument, designed in 1677 by Wren and Robert Hooke, was actually designed as "a unique, hugely ambitious, [and] vastly oversized scientific instrument." It used "strategically placed vents and vantage points," she found, to measure atmospheric pressure. It was not a building at all, in other words, but a rogue piece of laboratory equipment. But I digress. On some future night when I can't sleep, I'll just crawl out of bed and walk across an unlit garden into a large and silent dome out back where the roof cracks open with the help of hidden motors, and I'll look up through lenses at ancient laceworks of light, tracking moons, taking photographs of universal radiation, writing down the size of the cosmos... and I'll post my results on BLDGBLOG. The age of the home observatory has barely begun.

• • •Recommended (though rather dry): The Sun in the Church by J.L. Heilbron Earlier on BLDGBLOG: The Heliocentric Pantheon: An Interview with Walter Murch, The architecture of solar alignments, and Roadhenge

[Image: Marin Bunker by Ron's Log]. [Image: Marin Bunker by Ron's Log].My wife and I went out to the Marin Headlands yesterday, on a beautiful if windy October afternoon, to hike through the earthquake-prone hills of an upraised seabed, past the eroding concrete bunkers of the U.S. military – abstract monoliths left stranded in the landscape. They're now strange altars: the solid but empty geometry of power.  [Image: Battery by Kevin Collins; the hills are hollow precisely because they're fortified]. [Image: Battery by Kevin Collins; the hills are hollow precisely because they're fortified].As we walked out of the hills and got closer to the coast, we heard the distant ringing of buoys, like churches at sea, their bells tolling slowly amongst waves, framed by the Golden Gate Bridge in the distance. There were pine cones resting on the tops of rocks that tilted up and out of the ground like gravestones, and it was so silent sometimes we could make out the flapping of birds' wings. Gulls hovered semi-stationary at the exact confluence of hillside and wind: part of the landscape, rooted in air.  [Image: Portal by sigma, of Cydonian fame]. [Image: Portal by sigma, of Cydonian fame].But then, incredibly, because it's Fleet Week, the Blue Angels came roaring out of the sky, tracing aerial symmetries, and the muffled thump of a sonic boom echoed into the open door of a nearby bunker. It was two terrestrially competitive visions of the military colliding: one embedded in the Earth through excavation, the other colonizing the sky. (Earlier on BLDGBLOG: Bunker Archaeology).

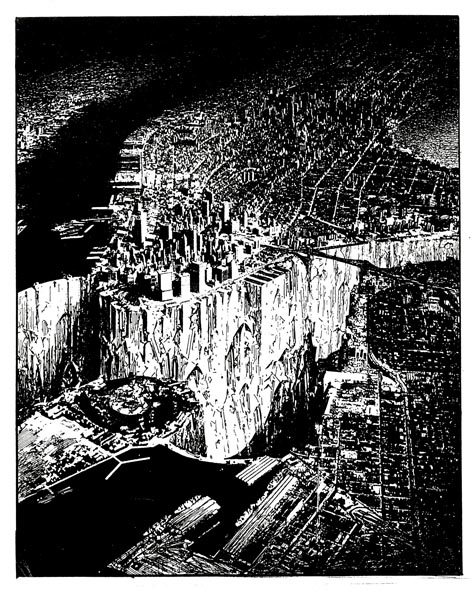

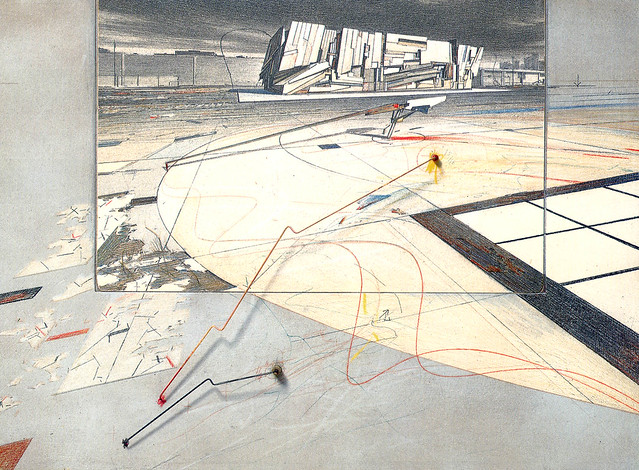

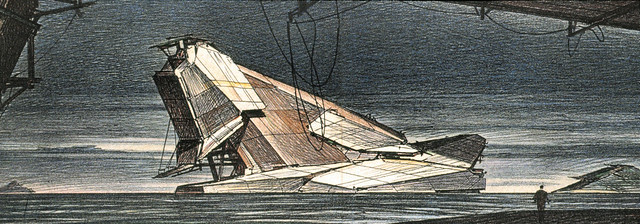

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, Lower Manhattan, 1999; view larger]. [Image: Lebbeus Woods, Lower Manhattan, 1999; view larger].

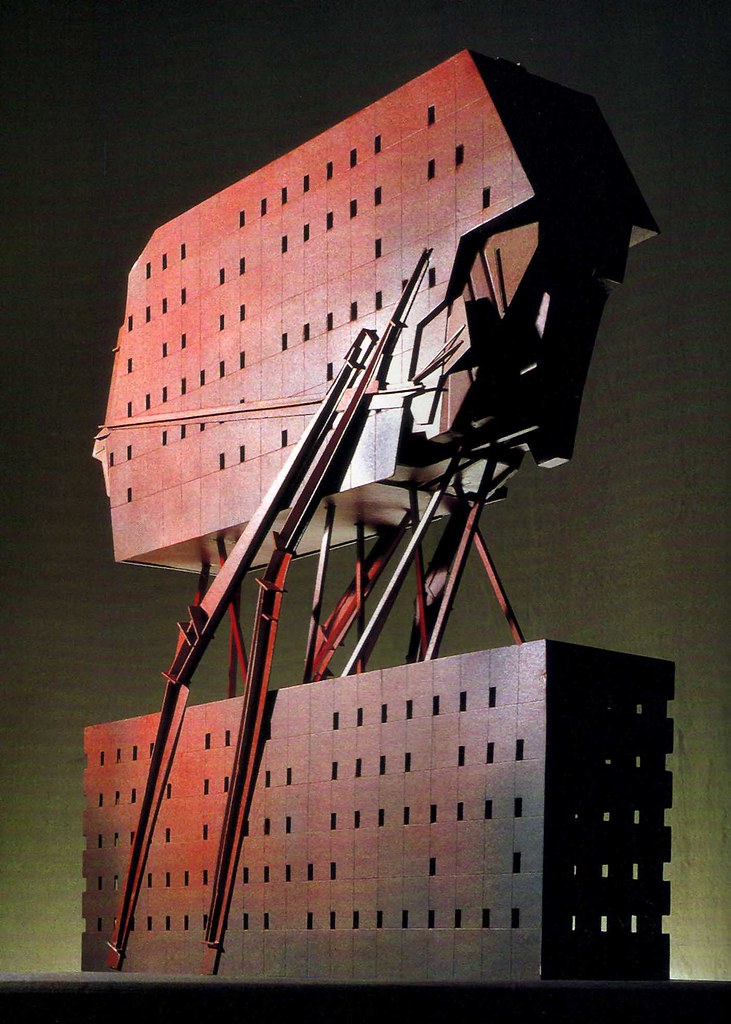

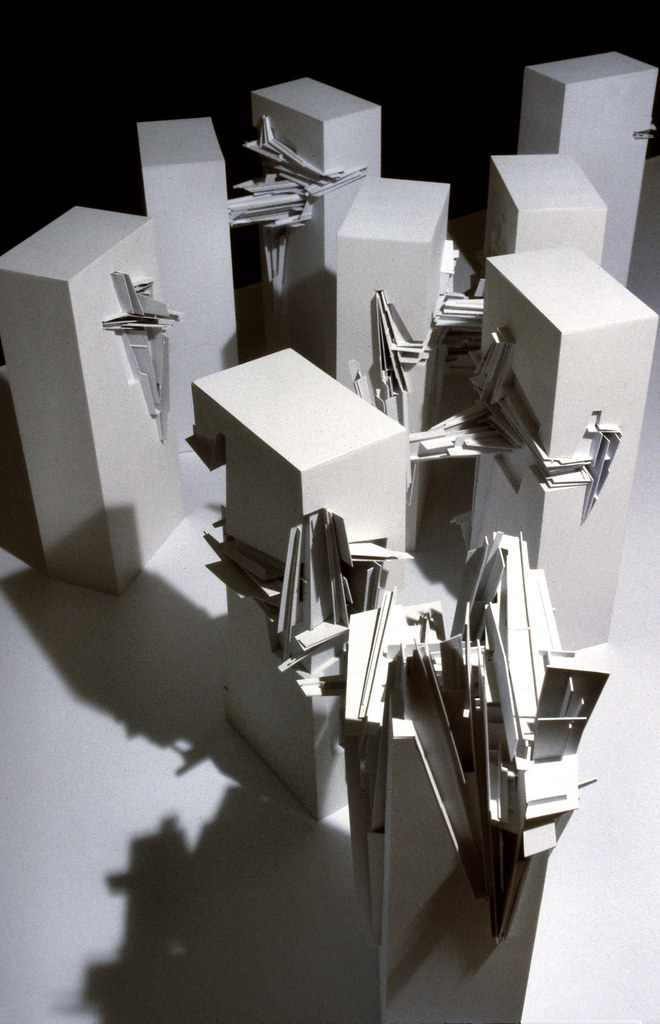

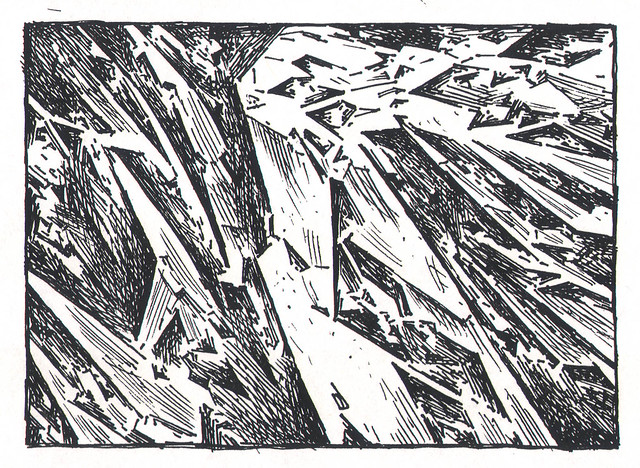

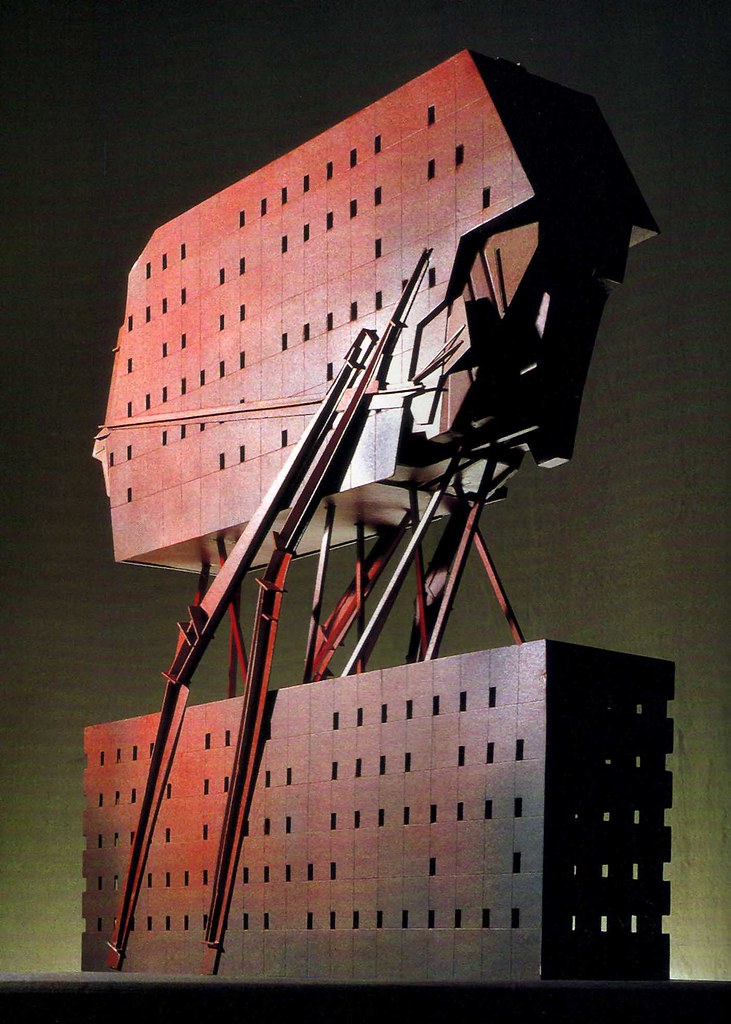

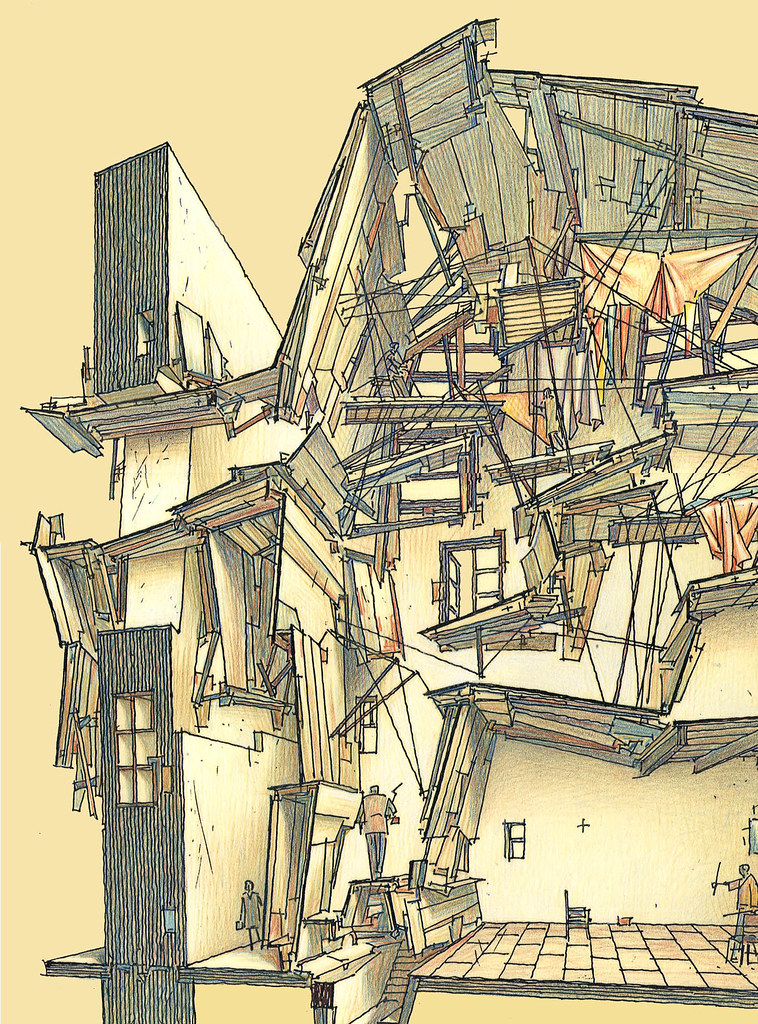

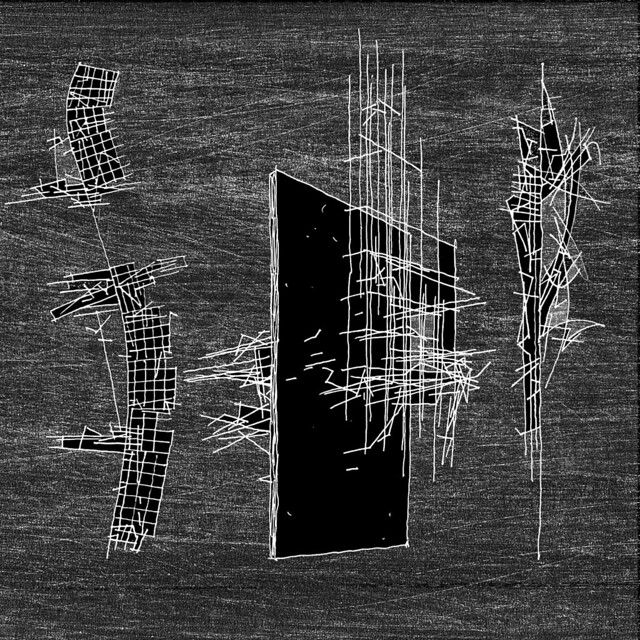

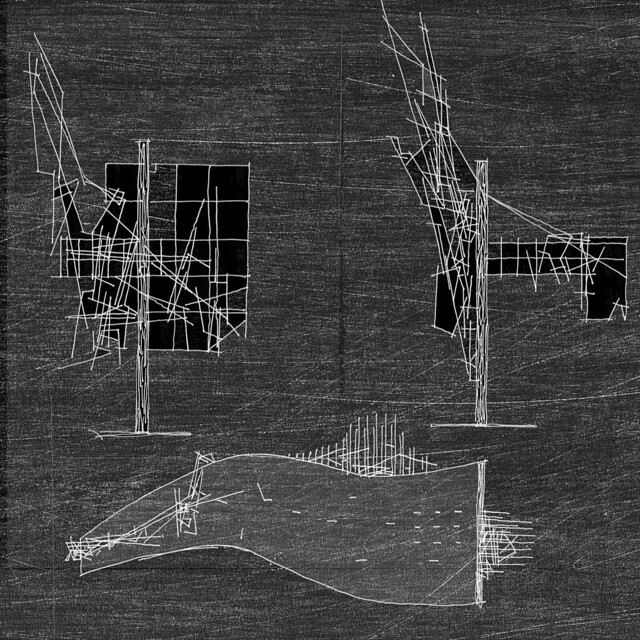

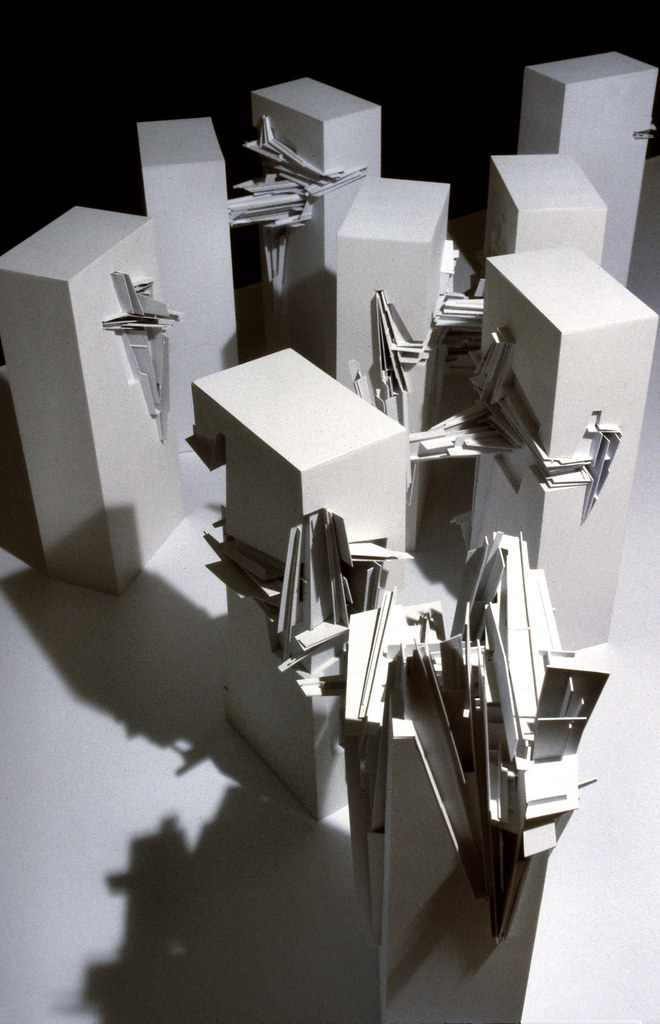

Lebbeus Woods is one of the first architects I knew by name – not Frank Lloyd Wright or Mies van der Rohe, but Lebbeus Woods – and it was Woods's own technically baroque sketches and models, of buildings that could very well be machines (and vice versa), that gave me an early glimpse of what architecture could really be about.

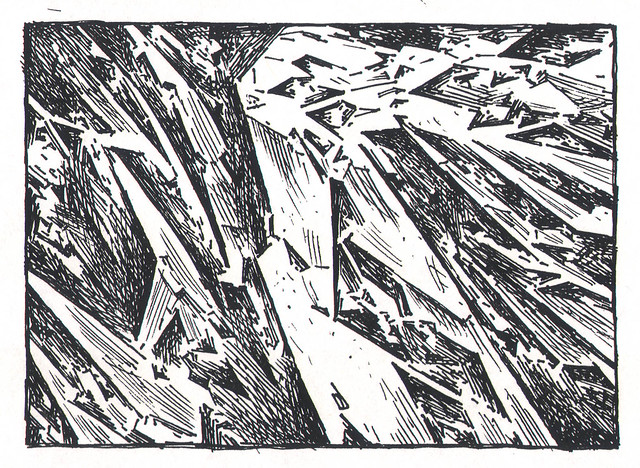

Woods's work is the exclamation point at the end of a sentence proclaiming that the architectural imagination, freed from constraints of finance and buildability, should be uncompromising, always. One should imagine entirely new structures, spaces without walls, radically reconstructing the outermost possibilities of the built environment.

If need be, we should re-think the very planet we stand on.

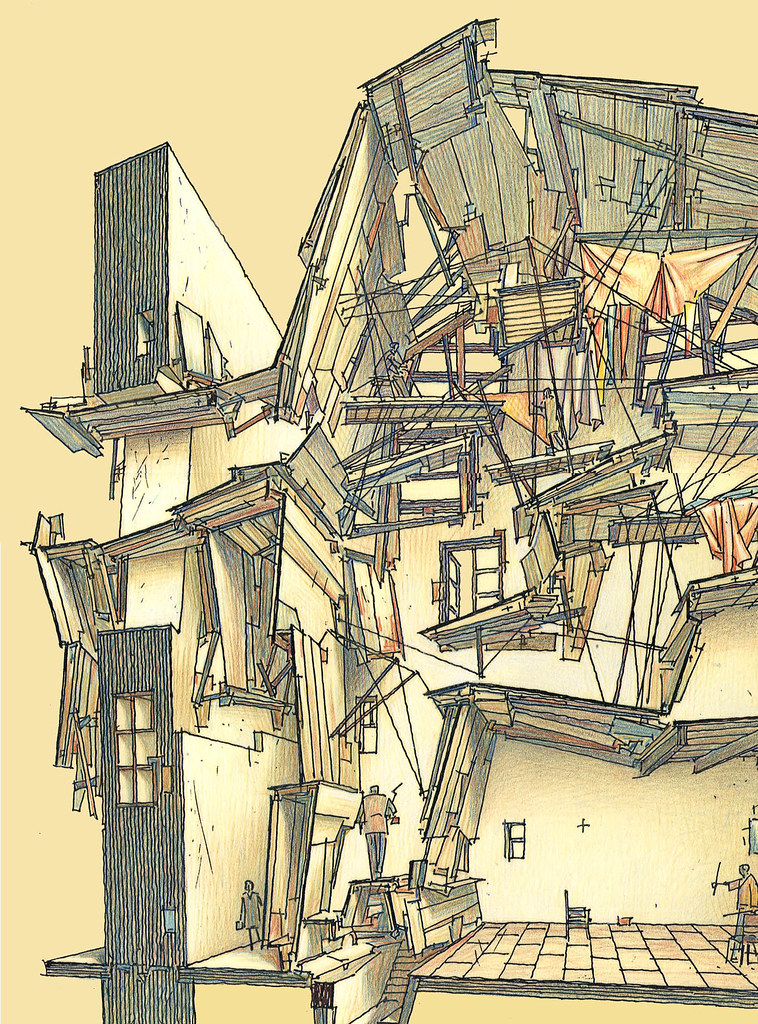

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, Havana, radically reconstructed, 1994]. [Image: Lebbeus Woods, Havana, radically reconstructed, 1994].

Of course, Woods is usually considered the avant-garde of the avant-garde, someone for whom architecture and science fiction – or urban planning and exhilarating, uncontained speculation – are all but one and the same. His work is experimental architecture in its most powerful, and politically provocative, sense.

Genres cross; fiction becomes reflection; archaeology becomes an unpredictable form of projective technology; and even the Earth itself gains an air of the non-terrestrial.

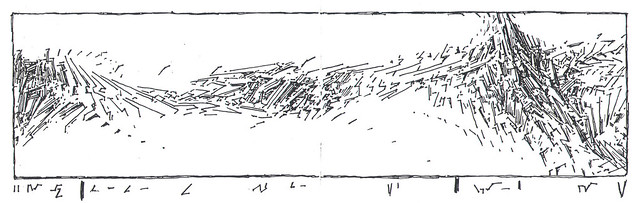

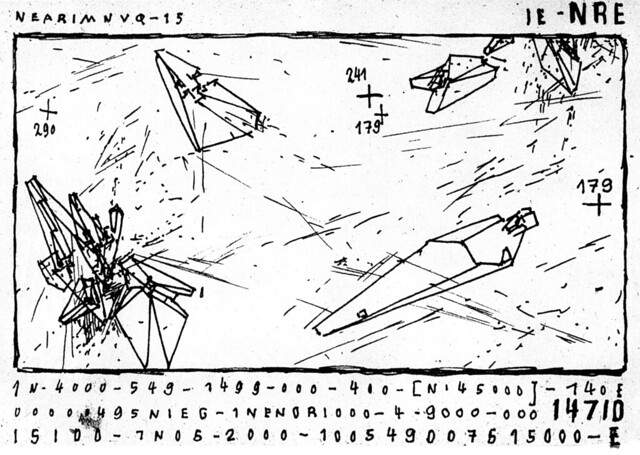

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, DMZ, 1988]. [Image: Lebbeus Woods, DMZ, 1988].

One project by Woods, in particular, captured my imagination – and, to this day, it just floors me. I love this thing. In 1980, Woods proposed a tomb for Albert Einstein – the so-called Einstein Tomb (collected here) – inspired by Boullée's famous Cenotaph for Newton.

But Woods's proposal wasn't some paltry gravestone or intricate mausoleum in hewn granite: it was an asymmetrical space station traveling on the gravitational warp and weft of infinite emptiness, passing through clouds of mutational radiation, riding electromagnetic currents into the void.

The Einstein Tomb struck me as such an ingenious solution to an otherwise unremarkable problem – how to build a tomb for an historically titanic mathematician and physicist – that I've known who Lebbeus Woods is ever since.

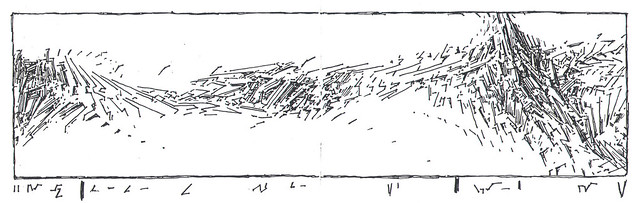

[Images: Lebbeus Woods, the city and the faults it sits on, from the San Francisco Bay Project, 1995]. [Images: Lebbeus Woods, the city and the faults it sits on, from the San Francisco Bay Project, 1995].

So when the opportunity came to talk to Lebbeus about one image that he produced nearly a decade ago, I continued with the questions; the result is this interview, which happily coincides with the launch of Lebbeus's own website – his first – at lebbeuswoods.net. That site contains projects, writings, studio reports, and some external links, and it's worth bookmarking for later exploration.

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, Havana, 1994; view larger]. [Image: Lebbeus Woods, Havana, 1994; view larger].

In the following Q&A, then, Woods talks to BLDGBLOG about the geology of Manhattan; the reconstruction of urban warzones; politics, walls, and cooperative building projects in the future-perfect tense; and the networked forces of his most recent installations.

• • •

BLDGBLOG: First, could you explain the origins of the Lower Manhattan image?

Lebbeus Woods: This was one of those occasions when I got a request from a magazine – which is very rare. In 1999, Abitare was making a special issue on New York City, and they invited a number of architects – like Steven Holl, Rafael Viñoly, and, oh god, I don’t recall. Todd Williams and Billie Tsien. Michael Sorkin. Myself. They invited us to make some sort of comment about New York. So I wrote a piece – probably 1000 words, 800 words – and I made the drawing.

I think the main thought I had, in speculating on the future of New York, was that, in the past, a lot of discussions had been about New York being the biggest, the greatest, the best – but that all had to do with the size of the city. You know, the size of the skyscrapers, the size of the culture, the population. So I commented in the article about Le Corbusier’s infamous remark that your skyscrapers are too small. Of course, New York dwellers thought he meant, oh, they’re not tall enough – but what he was referring to was that they were too small in their ground plan. His idea of the Radiant City and the Ideal City – this was in the early 30s – was based on very large footprints of buildings, separated by great distances, and, in between the buildings in his vision, were forests, parks, and so forth. But in New York everything was cramped together because the buildings occupied such a limited ground area. So Le Corbusier was totally misunderstood by New Yorkers who thought, oh, our buildings aren’t tall enough – we’ve got to go higher! Of course, he wasn’t interested at all in their height – more in their plan relationship. Remember, he’s the guy who said, the plan is the generator.

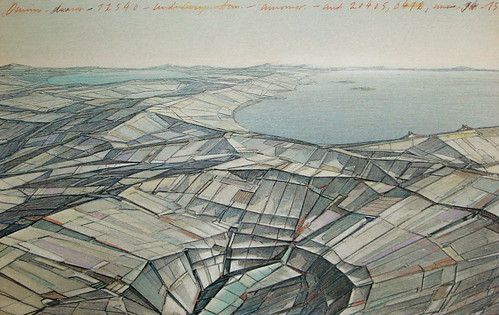

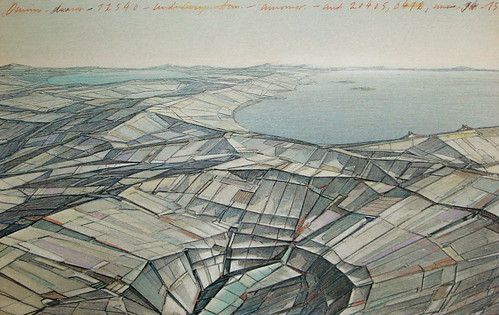

So I was speculating on the future of the city and I said, well, obviously, compared to present and future cities, New York is not going to be able to compete in terms of size anymore. It used to be a large city, but now it’s a small city compared with São Paulo, Mexico City, Kuala Lumpur, or almost any Asian city of any size. So I said maybe New York can establish a new kind of scale – and the scale I was interested in was the scale of the city to the Earth, to the planet. I made the drawing as a demonstration of the fact that Manhattan exists, with its towers and skyscrapers, because it sits on a rock – on a granite base. You can put all this weight in a very small area because Manhattan sits on the Earth. Let’s not forget that buildings sit on the Earth.

I wanted to suggest that maybe lower Manhattan – not lower downtown, but lower in the sense of below the city – could form a new relationship with the planet. So, in the drawing, you see that the East River and the Hudson are both dammed. They’re purposefully drained, as it were. The underground – or lower Manhattan – is revealed, and, in the drawing, there are suggestions of inhabitation in that lower region.

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, Lower Manhattan, 1999, in case you missed it; view larger]. [Image: Lebbeus Woods, Lower Manhattan, 1999, in case you missed it; view larger].

So it was a romantic idea – and the drawing is very conceptual in that sense.

But the exposure of the rock base, or the underground condition of the city, completely changes the scale relationship between the city and its environment. It’s peeling back the surface to see what the planetary reality is. And the new scale relationship is not about huge blockbuster buildings; it’s not about towers and skyscrapers. It’s about the relationship of the relatively small human scratchings on the surface of the earth compared to the earth itself. I think that comes across in the drawing. It’s not geologically correct, I’m sure, but the idea is there.

There are a couple of other interesting features which I’ll just mention. One is that the only bridge I show is the Brooklyn Bridge. I don’t show the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel, for instance. That’s just gone. And I don’t show the Manhattan Bridge or the Williamsburg Bridge, which are the other two bridges on the East River. On the Hudson side, it was interesting, because I looked carefully at the drawings – which I based on an aerial photograph of Manhattan, obviously – and the World Trade Center… something’s going on there. Of course, this was in 1999, and I’m not a prophet and I don’t think that I have any particular telepathic or clairvoyant abilities [ laughs], but obviously the World Trade Center has been somehow diminished, and there are things floating in the Hudson next to it. I’m not sure exactly what I had in mind – it was already several years ago – except that some kind of transformation was going to happen there.

BLDGBLOG: That’s actually one of the things I like so much about your work: you re-imagine cities and buildings and whole landscapes as if they have undergone some sort of potentially catastrophic transformation – be it a war or an earthquake, etc. – but you don’t respond to those transformations by designing, say, new prefab refugee shelters or more durable tents. You respond with what I’ll call science fiction: a completely new order of things – a new way of organizing and thinking about space. You posit something radically different than what was there before. It’s exciting.

Woods: Well, I think that, for instance, in Sarajevo, I was trying to speculate on how the war could be turned around, into something that people could build the new Sarajevo on. It wasn’t about cleaning up the mess or fixing up the damage; it was more about a transformation in the society and the politics and the economics through architecture. I mean, it was a scenario – and, I suppose, that was the kind of movie aspect to it. It was a “what if?”

I think there’s not enough of that thinking today in relation to cities that have been faced with sudden and dramatic – even violent – transformations, either because of natural or human causes. But we need to be able to speculate, to create these scenarios, and to be useful in a discussion about the next move. No one expects these ideas to be easily implemented. It’s not like a practical plan that you should run out and do. But, certainly, the new scenario gives you a chance to investigate a direction. Of course, being an architect, I’m very interested in the specifics of that direction – you know, not just a verbal description but: this is what it might look like.

So that was the approach in Sarajevo – as well as in this drawing of Lower Manhattan, as I called it.

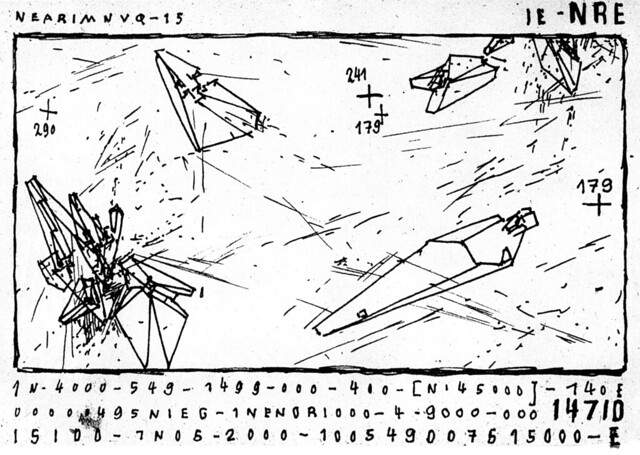

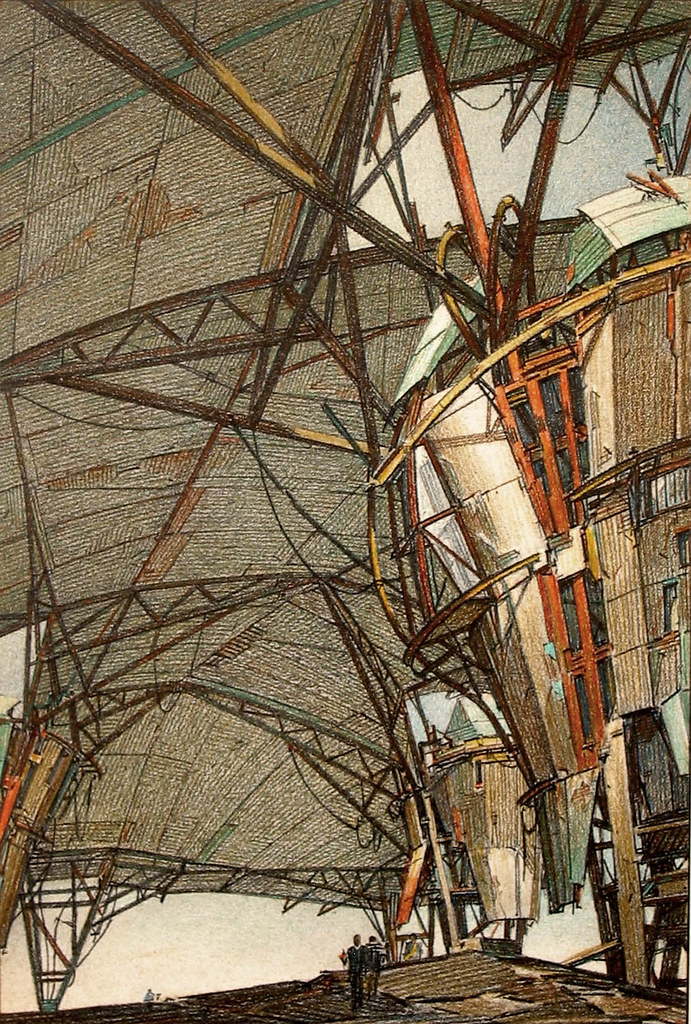

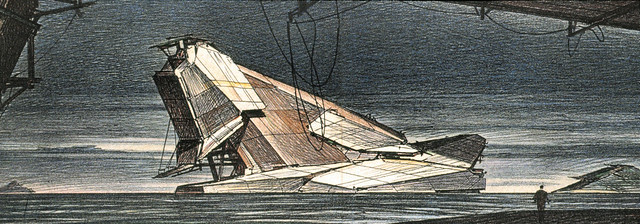

[Images: Lebbeus Woods. Future structures of the Korean demilitarized zone (1988) juxtaposed with two views of the architectonic tip of some vast flooded machine-building, from Icebergs (1991)].

BLDGBLOG [Images: Lebbeus Woods. Future structures of the Korean demilitarized zone (1988) juxtaposed with two views of the architectonic tip of some vast flooded machine-building, from Icebergs (1991)].

BLDGBLOG: Part of that comes from recognizing architecture as its own kind of genre. In other words, architecture has the ability, rivaling literature, to imagine and propose new, alternative routes out of the present moment. So architecture isn’t just buildings, it's a system of entirely re-imagining the world through new plans and scenarios.

Woods: Well, let me just back up and say that architecture is a multi-disciplinary field, by definition. But, as a multi-disciplinary field, our ideas have to be comprehensive; we can’t just say: “I’ve got a new type of column that I think will be great for the future of architecture.”

BLDGBLOG: [ laughs]

Woods: Maybe it will be great – but it’s not enough. I think architects – at least those inclined to understand the multi-disciplinarity and the comprehensive nature of their field – have to visualize something that embraces all these political, economic, and social changes. As well as the technological. As well as the spatial.

But we’re living in a very odd time for the field. There’s a kind of lack of discourse about these larger issues. People are hunkered down, looking for jobs, trying to get a building. It’s a low point. I don’t think it will stay that way. I don’t think that architects themselves will allow that. After all, it’s architects who create the field of architecture; it’s not society, it’s not clients, it’s not governments. I mean, we architects are the ones who define what the field is about, right?

So if there’s a dearth of that kind of thinking at the moment, it’s because architects have retreated – and I’m sure a coming generation is going to say: hey, this retreat is not good. We’ve got to imagine more broadly. We have to have a more comprehensive vision of what the future is.

[Images: Lebbeus Woods, The Wall Game].

BLDGBLOG [Images: Lebbeus Woods, The Wall Game].

BLDGBLOG: In your own work – and I’m thinking here of the Korean DMZ project or the Israeli wall-game – this “more comprehensive vision” of the future also involves rethinking political structures. Engaging in society not just spatially, but politically. Many of the buildings that you’ve proposed are more than just buildings, in other words; they’re actually new forms of political organization.

Woods: Yeah. I mean, obviously, the making of buildings is a huge investment of resources of various kinds. Financial, as well as material, and intellectual, and emotional resources of a whole group of people get involved in a particular building project. And any time you get a group, you’re talking about politics. To me politics means one thing: How do you change your situation? What is the mechanism by which you change your life? That’s politics. That’s the political question. It’s about negotiation, or it’s about revolution, or it’s about terrorism, or it’s about careful step-by-step planning – all of this is political in nature. It’s about how people, when they get together, agree to change their situation.

As I wrote some years back, architecture is a political act, by nature. It has to do with the relationships between people and how they decide to change their conditions of living. And architecture is a prime instrument of making that change – because it has to do with building the environment they live in, and the relationships that exist in that environment.

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, Siteline Vienna, 1998].

BLDGBLOG [Image: Lebbeus Woods, Siteline Vienna, 1998].

BLDGBLOG: There’s also the incredibly interesting possibility that a building project, once complete, will actually change the society that built it. It’s the idea that a building – a work of architecture – could directly catalyze a transformation, so that the society that finishes building something is not the same society that set out to build it in the first place. The building changes them.

Woods: I love that. I love the way you put it, and I totally agree with it. I think, you know, architecture should not just be something that follows up on events but be a leader of events. That’s what you’re saying: That by implementing an architectural action, you actually are making a transformation in the social fabric and in the political fabric. Architecture becomes an instigator; it becomes an initiator.

That, of course, is what I’ve always promoted – but it’s the most difficult thing for people to do. Architects say: well, it’s my client, they won’t let me do this. Or: I have to do what my client wants. That’s why I don’t have any clients! [ laughter] It’s true.

Because at least I can put the ideas out there and somehow it might seep through, or filter through, to another level.

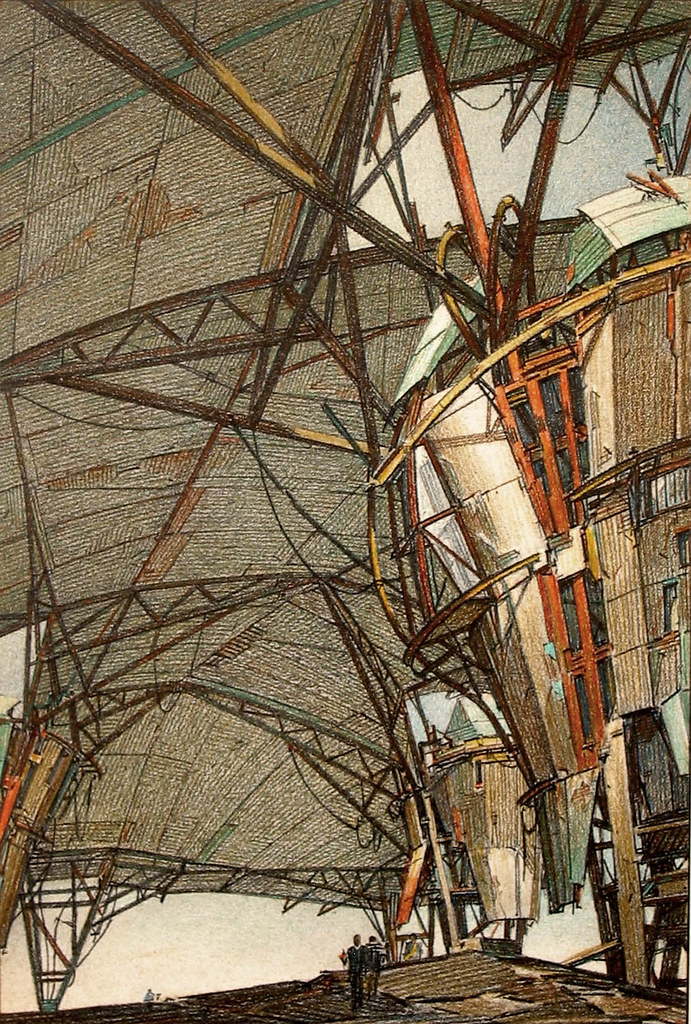

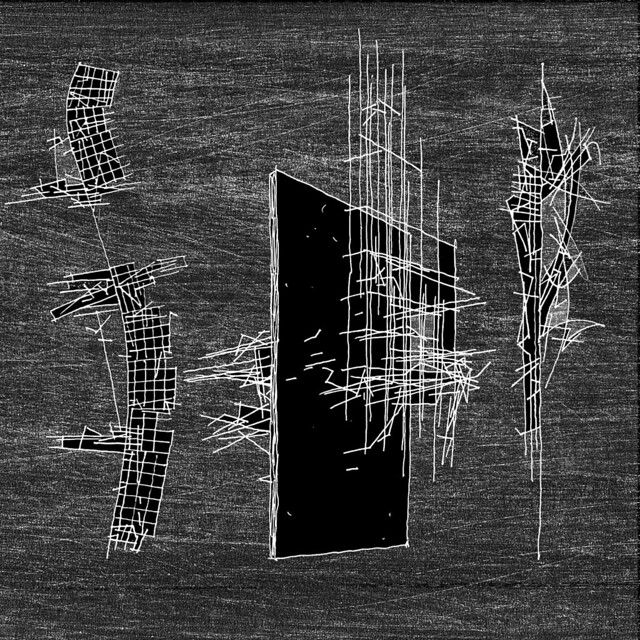

[Images: Lebbeus Woods, Nine Reconstructed Boxes].

BLDGBLOG [Images: Lebbeus Woods, Nine Reconstructed Boxes].

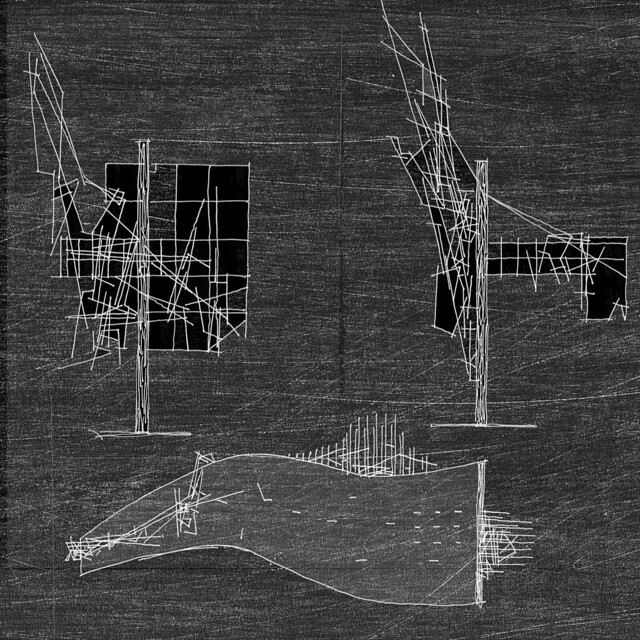

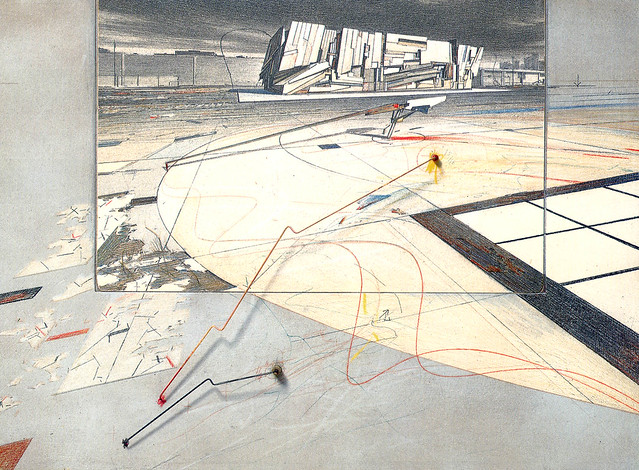

BLDGBLOG: Finally, it seems like a lot of the work you’ve been doing for the past few years – in Vienna, especially – has been a kind of architecture without walls. It’s almost pure space. In other words, instead of walls and floors and recognizable structures, you’ve been producing networks and forces and tangles and clusters – an abstract space of energy and directions. Is that an accurate way of looking at your recent work – and, if so, is this a purely aesthetic exploration, or is this architecture without walls meant to symbolize or communicate a larger political message?

Woods: Well, look – if you go back through my projects over the years, probably the least present aspect is the idea of property lines. There are certainly boundaries – spatial boundaries – because, without them, you can’t create space. But the idea of fencing off, or of compartmentalizing – or the capitalist ideal of private property – has been absent from my work over the last few years.

[Image: Lebbeus Woods. A drawing of tectonic faults and other subsurface tensions, from his San Francisco Bay Project, 1995]. [Image: Lebbeus Woods. A drawing of tectonic faults and other subsurface tensions, from his San Francisco Bay Project, 1995].

I think in my more recent work, certainly, there are still boundaries. There are still edges. But they are much more porous, and the property lines… [ laughs] are even less, should we say, defined or desired.

So the more recent work – like in Vienna, as you mentioned – is harder for people to grasp. Back in the early 90s I was confronting particular situations, and I was doing it in a kind of scenario way. I made realistic-looking drawings of places – of situations – but now I’ve moved into a purely architectonic mode. I think people probably scratch their heads a little bit and say: well, what is this? But I’m glad you grasp it – and I hope my comments clarify at least my aspirations.

Probably the political implication of that is something about being open – encouraging what I call the lateral movement and not the vertical movement of politics. It’s the definition of a space through a set of approximations or a set of vibrations or a set of energy fluctuations – and that has everything to do with living in the present.

All of those lines are in flux. They’re in movement, as we ourselves develop and change.

[Images: Lebbeus Woods, System Wien, 2005]. [Images: Lebbeus Woods, System Wien, 2005].

• • •

BLDGBLOG owes a huge thanks to Lebbeus Woods, not only for having this conversation but for proving over and over again that architecture can and should always be a form of radical reconstruction, unafraid to take on buildings, cities, worlds – whole planets.

For more images, meanwhile, including much larger versions of all the ones that appear here, don't miss BLDGBLOG's Lebbeus Woods Flickr set. Also consider stopping by Subtopia for an enthusiastic recap of Lebbeus's appearance at Postopolis! last Spring; and by City of Sound for Dan Hill's synopsis of the same event.

|

|

We just had another earthquake.

We just had another earthquake.

[Image: By and via

[Image: By and via  [Image: By and via

[Image: By and via  [Image: By and via

[Image: By and via  [Image: By and via

[Image: By and via  [Image: White Noise/White Light, Athens, by

[Image: White Noise/White Light, Athens, by  [Image: White Noise/White Light, Athens, by

[Image: White Noise/White Light, Athens, by  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: The Great Lakes are draining; photo by James Rajotte for

[Image: The Great Lakes are draining; photo by James Rajotte for  [Image: Lebbeus Woods, Lower Manhattan; view

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, Lower Manhattan; view  [Image: Simon Norfolk, a photographer previously

[Image: Simon Norfolk, a photographer previously  But who knows – perhaps 2008 is the year N.A.W.A.P.A. makes a comeback. Or, perhaps, in January 2010, after another dry winter, Los Angeles voters will start to get thirsty. Perhaps some well-positioned Senators, in 2011, might even start making phonecalls north. Perhaps, in 2012, some recent graduates from water management programs at state-funded universities in Illinois or Utah might catch the itch of moral rebellion; they might then start redrawing their personal maps of the continent, going to bed at night with visions of massive dams in their heads, writing position papers for peer-reviewed hydrological engineering magazines.

But who knows – perhaps 2008 is the year N.A.W.A.P.A. makes a comeback. Or, perhaps, in January 2010, after another dry winter, Los Angeles voters will start to get thirsty. Perhaps some well-positioned Senators, in 2011, might even start making phonecalls north. Perhaps, in 2012, some recent graduates from water management programs at state-funded universities in Illinois or Utah might catch the itch of moral rebellion; they might then start redrawing their personal maps of the continent, going to bed at night with visions of massive dams in their heads, writing position papers for peer-reviewed hydrological engineering magazines.  [Image: A fish-cleaning station in Las Vegas Bay, now abandoned by the West's sinking waters; taken by

[Image: A fish-cleaning station in Las Vegas Bay, now abandoned by the West's sinking waters; taken by  [Image: Lake Lanier, Atlanta's primary source of drinking water, gets lower and lower; photo by Pouya Dianat for The Atlanta Journal-Constitution].

[Image: Lake Lanier, Atlanta's primary source of drinking water, gets lower and lower; photo by Pouya Dianat for The Atlanta Journal-Constitution].

[Images: Lawrence Weschler and BLDGBLOG at the

[Images: Lawrence Weschler and BLDGBLOG at the  First, a general note: as some of you may know, I'm in the process of turning BLDGBLOG into

First, a general note: as some of you may know, I'm in the process of turning BLDGBLOG into  [Image: Zoe Crosher's new pamphlet, published by the

[Image: Zoe Crosher's new pamphlet, published by the

[Images: (top) A wonderful – stunning! – photo of Rome, with the dome of St. Peter's catching sunlight in the background, by

[Images: (top) A wonderful – stunning! – photo of Rome, with the dome of St. Peter's catching sunlight in the background, by  [Image: 33 Thomas Street, via

[Image: 33 Thomas Street, via  [Image: The fires of chromosomal mutation burn].

[Image: The fires of chromosomal mutation burn].

[Images: The future of the Brazilian Earth, photographed by Lalo de Almeida for

[Images: The future of the Brazilian Earth, photographed by Lalo de Almeida for  [Images: Libya's ambitious plan is announced; via the

[Images: Libya's ambitious plan is announced; via the  [Image: A rendering of the Libyan eco-region, ©Foster + Partners, via the

[Image: A rendering of the Libyan eco-region, ©Foster + Partners, via the  [Image: A Venusian mountain called Maat Mons; via

[Image: A Venusian mountain called Maat Mons; via  [Image: The Hong Kong-Shenzhen Super-City as mapped by the

[Image: The Hong Kong-Shenzhen Super-City as mapped by the

[Image: L.A., as photographed by

[Image: L.A., as photographed by  [Image: An extraordinary photograph, called 4.366 Braille, by

[Image: An extraordinary photograph, called 4.366 Braille, by  [Image: Two beautiful photos by

[Image: Two beautiful photos by  In case anyone reading this happens to be in Los Angeles over the next few days, I'll be flying back to that city of individualized car geographies tomorrow to give a talk at UCLA's

In case anyone reading this happens to be in Los Angeles over the next few days, I'll be flying back to that city of individualized car geographies tomorrow to give a talk at UCLA's  [Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: A

[Image: A  [Image: Another

[Image: Another  [Images: Michelle Litvin for

[Images: Michelle Litvin for  [Images: Erik Davies for

[Images: Erik Davies for  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: The Church of

[Image: The Church of  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, Lower Manhattan, 1999; view

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, Lower Manhattan, 1999; view  [Image: Lebbeus Woods, Havana, radically reconstructed, 1994].

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, Havana, radically reconstructed, 1994]. [Image: Lebbeus Woods, DMZ, 1988].

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, DMZ, 1988].

[Images: Lebbeus Woods, the city and the faults it sits on, from the San Francisco Bay Project, 1995].

[Images: Lebbeus Woods, the city and the faults it sits on, from the San Francisco Bay Project, 1995]. [Image: Lebbeus Woods, Havana, 1994; view

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, Havana, 1994; view  [Image: Lebbeus Woods, Lower Manhattan, 1999, in case you missed it; view

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, Lower Manhattan, 1999, in case you missed it; view

[Images: Lebbeus Woods. Future structures of the Korean demilitarized zone (1988) juxtaposed with two views of the architectonic tip of some vast flooded machine-building, from Icebergs (1991)].

[Images: Lebbeus Woods. Future structures of the Korean demilitarized zone (1988) juxtaposed with two views of the architectonic tip of some vast flooded machine-building, from Icebergs (1991)].

[Images: Lebbeus Woods, The Wall Game].

[Images: Lebbeus Woods, The Wall Game]. [Image: Lebbeus Woods, Siteline Vienna, 1998].

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, Siteline Vienna, 1998].

[Images: Lebbeus Woods, Nine Reconstructed Boxes].

[Images: Lebbeus Woods, Nine Reconstructed Boxes]. [Image: Lebbeus Woods. A drawing of tectonic faults and other subsurface tensions, from his San Francisco Bay Project, 1995].

[Image: Lebbeus Woods. A drawing of tectonic faults and other subsurface tensions, from his San Francisco Bay Project, 1995].

[Images: Lebbeus Woods, System Wien, 2005].

[Images: Lebbeus Woods, System Wien, 2005].