Earth Evolves

I've been looking at Ron Blakey's maps of the tectonic evolution of the earth's surface again, and I just absolutely love these things.

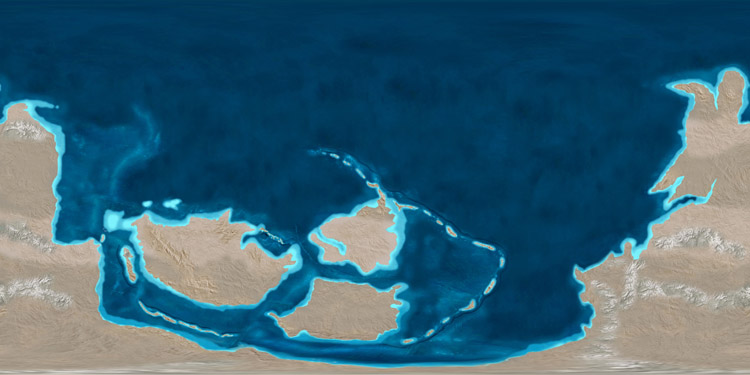

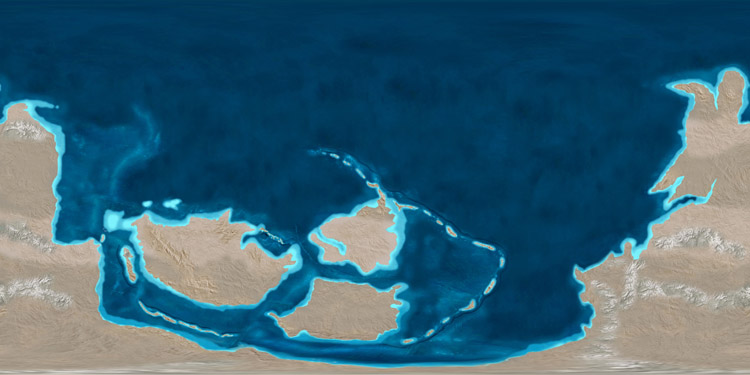

[Image: The earth 600 million years ago, in the late Precambrian Era; mapped by Ron Blakey].

[Image: The earth 600 million years ago, in the late Precambrian Era; mapped by Ron Blakey].

In fact, I think Blakey should be given some sort of science prize for putting these together; these help to visualize broad historical processes in a way that is visually clear, conceptually unforgettable, and imaginatively provocative, to say the least. And these images, posted here, are only one series among many that Blakey's assembled – and these aren't even all the images in that series. For that, you'll have to visit Blakey's site.

So what you're looking at here is continental drift over a period of 600 million years, beginning with the Late Precambrian Era, above, through to the present day, in the penultimate image, below.

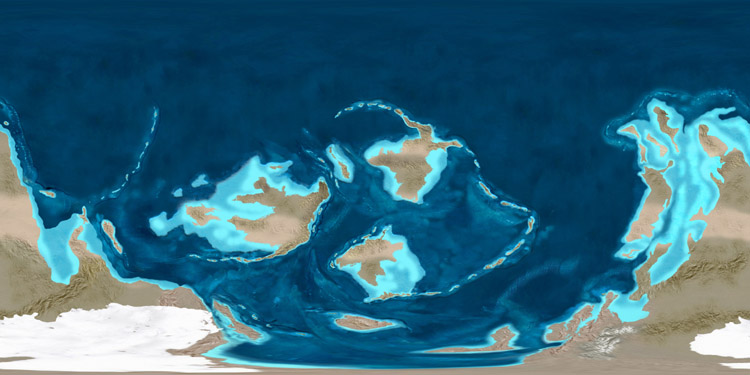

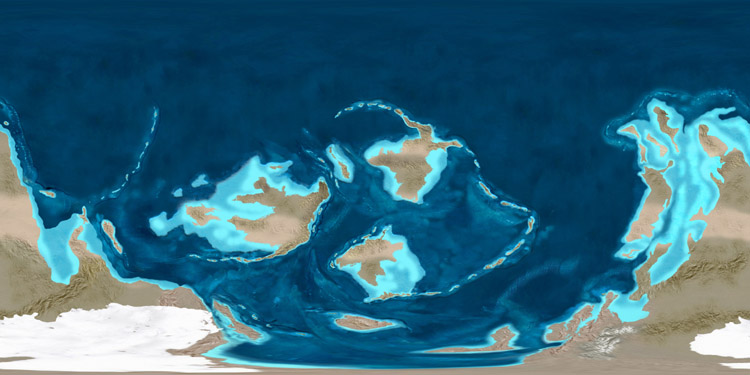

[Images: The tectonic paleo-history of the earth; mapped by Ron Blakey].

[Images: The tectonic paleo-history of the earth; mapped by Ron Blakey].

That sequence of four images, above, gives us the earth as a kind of northward spray of island arcs and micro-continents, small landmasses moving toward evolutionary isolation.

What must it have been like, I wonder, if we could somehow have taken a sailboat in and around those tropical seas, weaving through vast semicircular island chains, finding reefs and bays, lagoons and inlets, anchoring offshore and camping on the beaches of an absolutely dark earth, electricity-less and lit from above by stars – with all the constellations different back then, as even the galaxy itself is still unfolding, full of alien patterns in the sky.

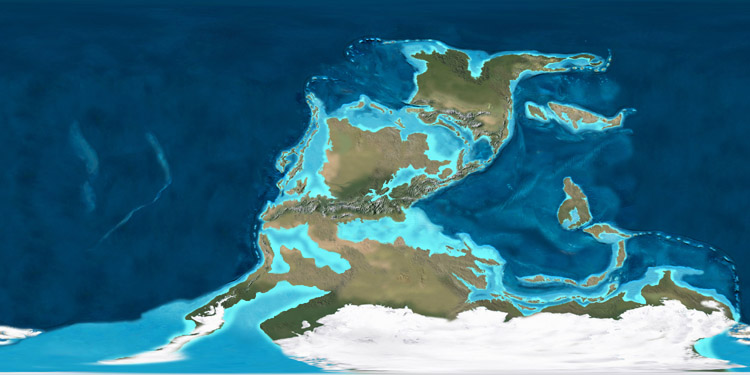

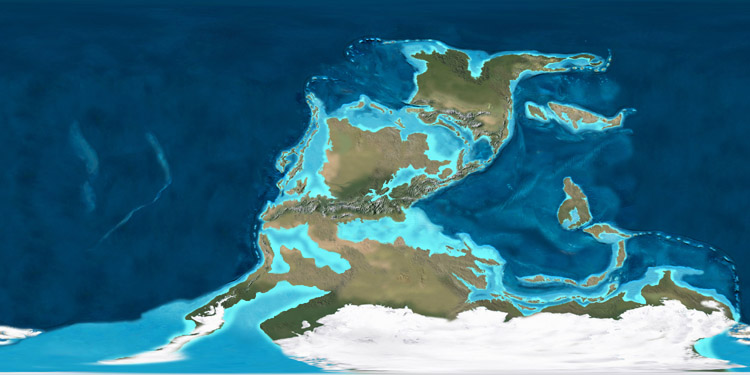

[Images: The tectonic paleo-history of the earth; in the last two images, you can see recognizable landmasses just beginning to form. Maps by Ron Blakey].

[Images: The tectonic paleo-history of the earth; in the last two images, you can see recognizable landmasses just beginning to form. Maps by Ron Blakey].

Something else that fascinates me – and you can see this in the next three images – is the fact that, until relatively recently, Europe was actually an Indonesia-like archipelago, distributed throughout warm northern latitude waters. One of the residues of this geography is a massive fossilized reef that I wrote about here on BLDGBLOG almost exactly two years ago.

Referring to that reef in an article from 1991, New Scientist wrote that, "if we could travel 160 million years back in time," we would find a reef "that occupied most of what is now Europe."

[Images: The earth from roughly 150 million years ago to 50 million years ago; mapped by Ron Blakey].

[Images: The earth from roughly 150 million years ago to 50 million years ago; mapped by Ron Blakey].

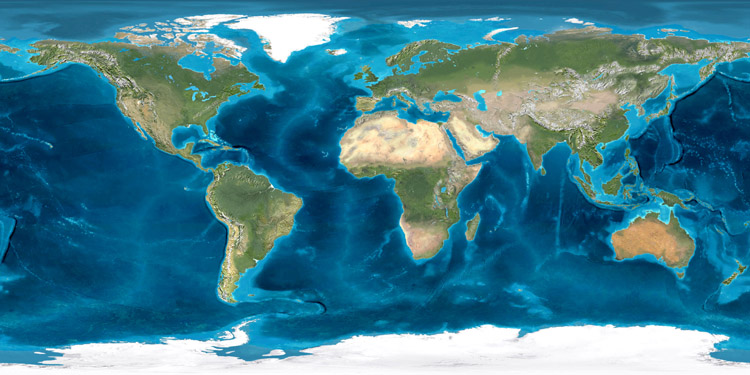

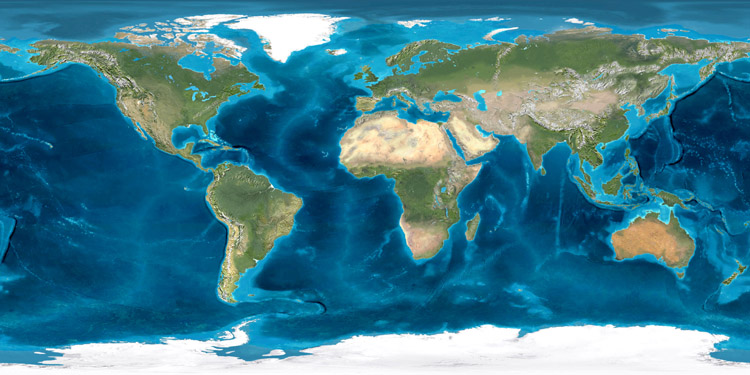

Then, of course, we hit the present day – pictured below.

Suddenly this arrangement looks rather impermanent.

[Image: The earth in its present continental configuration; mapped by Ron Blakey].

[Image: The earth in its present continental configuration; mapped by Ron Blakey].

It's extraordinary to realize, then, that this sequence of images represents only 600 million years of geological time – because the earth has something like seven and a half billion years to go before solar extinction. And though plate tectonics may actually cease someday, let's say that a healthy billion and a half more years of continental rearrangement are still in store for this world; what fantastic inland seas and archipelagos might yet be waiting to form?

Extrapolating from these very images into the future, as our planet continues to delink and spread, maneuvering its surfaces around in endless reconfigurations, is a time-consuming but worthwhile thought experiment; if we could get Blakey to speculate upon the tectonic future of the earth, for instance, that would indeed be something to see.

Of course, this is something that New Scientist actually wrote about this past winter, suggesting three possible evolutionary scenarios for where these nomadic fragments of our planet's surface might end up:

[Image: Three possible supercontinents, as mapped by New Scientist: Novopangaea, Amasia, and Pangaea Proxima; view larger].

[Image: Three possible supercontinents, as mapped by New Scientist: Novopangaea, Amasia, and Pangaea Proxima; view larger].

As if these things are a matter of preference, let me absurdly point out that I am actually not a big fan of supercontinents; I think they're boring. Luckily, they seem to crack apart based upon their own weight and bulk; in other words, like many Americans, supercontinents are too heavy for their own good.

Personally, I like archipelagos and island arcs.

In fact, might there be some way to hack the earth's surface and ensure a supercontinent-free planet to come? We could somehow help certain portions of the earth's surface to unzip, forming new island chains, and we could perforate continental shields the world over to assist with their future fragmentation...

In any case, what's also interesting about these maps is that, taken as a whole, the last 600 million years appear really to have been a kind of mass northward migration of landmasses, as if the continents were pulled from one pole to the other by temporary, if monumental, spreading and subduction zones.

Again, though, these are not all the images in the series; for that, you'll have to check out Ron Blakey's website. And, seriously, someone needs to give this guy a fellowship or an award or something – these maps are just fantastic.

[Image: These images are also available in a small Flickr set].

[Image: The earth 600 million years ago, in the late Precambrian Era; mapped by Ron Blakey].

[Image: The earth 600 million years ago, in the late Precambrian Era; mapped by Ron Blakey].In fact, I think Blakey should be given some sort of science prize for putting these together; these help to visualize broad historical processes in a way that is visually clear, conceptually unforgettable, and imaginatively provocative, to say the least. And these images, posted here, are only one series among many that Blakey's assembled – and these aren't even all the images in that series. For that, you'll have to visit Blakey's site.

So what you're looking at here is continental drift over a period of 600 million years, beginning with the Late Precambrian Era, above, through to the present day, in the penultimate image, below.

[Images: The tectonic paleo-history of the earth; mapped by Ron Blakey].

[Images: The tectonic paleo-history of the earth; mapped by Ron Blakey].That sequence of four images, above, gives us the earth as a kind of northward spray of island arcs and micro-continents, small landmasses moving toward evolutionary isolation.

What must it have been like, I wonder, if we could somehow have taken a sailboat in and around those tropical seas, weaving through vast semicircular island chains, finding reefs and bays, lagoons and inlets, anchoring offshore and camping on the beaches of an absolutely dark earth, electricity-less and lit from above by stars – with all the constellations different back then, as even the galaxy itself is still unfolding, full of alien patterns in the sky.

[Images: The tectonic paleo-history of the earth; in the last two images, you can see recognizable landmasses just beginning to form. Maps by Ron Blakey].

[Images: The tectonic paleo-history of the earth; in the last two images, you can see recognizable landmasses just beginning to form. Maps by Ron Blakey].Something else that fascinates me – and you can see this in the next three images – is the fact that, until relatively recently, Europe was actually an Indonesia-like archipelago, distributed throughout warm northern latitude waters. One of the residues of this geography is a massive fossilized reef that I wrote about here on BLDGBLOG almost exactly two years ago.

Referring to that reef in an article from 1991, New Scientist wrote that, "if we could travel 160 million years back in time," we would find a reef "that occupied most of what is now Europe."

- At first sight this reef and its communities have striking similarities to the Great Barrier Reef. But this ancient reef structure is unique; its main architects were not corals, but multicellular marine sponges, many of which have no match today. And this reef was even bigger than the Great Barrier Reef. Its fossil remains stretch about 2900 kilometeres from southern Spain to eastern Romania, making it one of the largest living structures ever to have existed on Earth.

[Images: The earth from roughly 150 million years ago to 50 million years ago; mapped by Ron Blakey].

[Images: The earth from roughly 150 million years ago to 50 million years ago; mapped by Ron Blakey].Then, of course, we hit the present day – pictured below.

Suddenly this arrangement looks rather impermanent.

[Image: The earth in its present continental configuration; mapped by Ron Blakey].

[Image: The earth in its present continental configuration; mapped by Ron Blakey]. It's extraordinary to realize, then, that this sequence of images represents only 600 million years of geological time – because the earth has something like seven and a half billion years to go before solar extinction. And though plate tectonics may actually cease someday, let's say that a healthy billion and a half more years of continental rearrangement are still in store for this world; what fantastic inland seas and archipelagos might yet be waiting to form?

Extrapolating from these very images into the future, as our planet continues to delink and spread, maneuvering its surfaces around in endless reconfigurations, is a time-consuming but worthwhile thought experiment; if we could get Blakey to speculate upon the tectonic future of the earth, for instance, that would indeed be something to see.

Of course, this is something that New Scientist actually wrote about this past winter, suggesting three possible evolutionary scenarios for where these nomadic fragments of our planet's surface might end up:

- Geologists now suspect that the movements of the Earth's continents are cyclical, and that every 500 to 700 million years they clump together. Unfolding over a period three times as long as it takes our solar system to orbit the centre of the galaxy, this is one of nature's grandest patterns. So what drives this cycle, and what will life be like next time the continents meet?

[Image: Three possible supercontinents, as mapped by New Scientist: Novopangaea, Amasia, and Pangaea Proxima; view larger].

[Image: Three possible supercontinents, as mapped by New Scientist: Novopangaea, Amasia, and Pangaea Proxima; view larger].As if these things are a matter of preference, let me absurdly point out that I am actually not a big fan of supercontinents; I think they're boring. Luckily, they seem to crack apart based upon their own weight and bulk; in other words, like many Americans, supercontinents are too heavy for their own good.

Personally, I like archipelagos and island arcs.

In fact, might there be some way to hack the earth's surface and ensure a supercontinent-free planet to come? We could somehow help certain portions of the earth's surface to unzip, forming new island chains, and we could perforate continental shields the world over to assist with their future fragmentation...

In any case, what's also interesting about these maps is that, taken as a whole, the last 600 million years appear really to have been a kind of mass northward migration of landmasses, as if the continents were pulled from one pole to the other by temporary, if monumental, spreading and subduction zones.

Again, though, these are not all the images in the series; for that, you'll have to check out Ron Blakey's website. And, seriously, someone needs to give this guy a fellowship or an award or something – these maps are just fantastic.

[Image: These images are also available in a small Flickr set].

Comments are moderated.

If it's not spam, it will appear here shortly!

Amazing find! I wish I could have more to say but the images have left me speechless.

By the way as a long-time lurker but first-time commenter I also just wanted to say that I always enjoy reading your posts. Looking forward to reading many more!

Absolutely fantastic images! I loved learning about this stuff in High school.

ok, you have got to see these animations, which are poorly presented.

nice images.

interesting you bring up the view of the stars from earth while showing how earth changed shape over time.

i can't remember where i read it, but there is apparently going to be a time in the future where the sky will be much blacker, cuz the universe will have expanded away so far that we will no longer be able to see most of it. sounds boring, like pangaea-nic earth, but worse is that future astronomers would no longer be able to infer things like the big bang anymore. entire areas of physics would simply not occur to them at all cuz the physical universe will not lead to the right questions. can't help but wonder what future physicists will come up with instead of string theory...

WOW. The images reminded me of a flower opening.

And the whole Europe/reef thing is just amazing to think about. Mind boggling.

This kind of post is exactly why I love BLDGBLOG!

read GENISIS BOOK 1 ..........THIS IS THEORETICAL DIARETIC THINKING ...

I saw an animation of the plates moving around with the earth spinning. It looks like antarctica is sitting on the bottom, spinning but not moving, while the rest of the continents are thrown out around the equator by centrifugal force. The arctic likewise stays as open water. I wonder if this is a stable configuration?

Interesting. Except that I'm a 130 lb. American, so if that's the basis of your hypothesis, you may consider a revision omitting overgeneralization.

Indeed this is a good, piece of scientific evidence to prove the fact that during time immemorial the entire world was in absolute absence of any religion, which comes to the conclusion that the religion of today's every religion is simple a rubber stamp religion. But searching through the ancient scriptures of vedas it clearly says that the entire earth was one called "Mahabharata" which is now wrongly reffered as India.

And simple to reject the fact that the technology was low is of no foundation at all. Because, ppl of that time had some thing Gr8 with their minds, i mean they could perceive things which we cant today do. Just like the dogs have got good smelling capacity the human brain had also some exposed perception capabilities before, and that would have brought the ppl of that age to arrive at some mind boggling scientific conclusion which are true infact.

I just stumbled upon this fascinating series of videos - 'evidence' that the earth is in fact *growing* - that the current continents fit together perfectly on a smaller sphere... even if it's nonsense, the videos are pretty compelling.

Think it'd be a good candidate for the BLDGBLOG treatment - haven't seen much on plate tectonics in a while.

http://www.nealadams.com/nmu.html

Commenting on an "old" post but hey, considering the subject matter covers millions of years, I hardly think a measly 3 years is of concern.

I just have one disagreement with you. You may be a fan of archipelagos, but I still say as far as life on earth is concerned, a supercontinent or otherwise large clumping together of landmass would be good. The islandisation of habitats ends up with situations such as the dodo.

Of course, I don't like the idea of the amount of desert involved in supercontinents, which is why I'm quite fond of the landlocked sea in the Pangaea Ultima/Proxima model - having stretches of water break the land up is in that respect good, but I still think land bridges would be beneficial to the evolution of solid, less vulnerable species.

Hope all that was easy to understand haha.

Post a Comment