The Architecture of Ascent

In what would merely have been an article about camping equipment in almost any other situation, revamped Italian architecture magazine Abitare recently took a fascinating look at portable mountain climbing shelters.

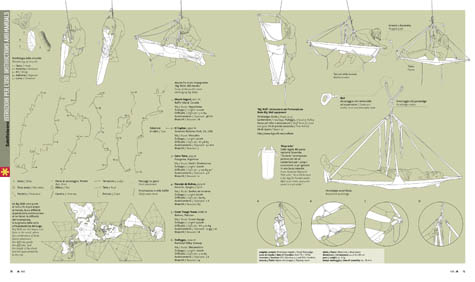

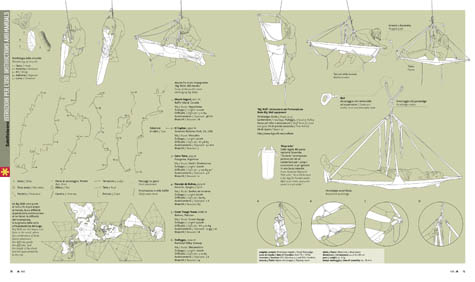

[Image: From an article by Jonathan Olivares, in Abitare; view much larger!].

[Image: From an article by Jonathan Olivares, in Abitare; view much larger!].

Viewed architecturally, these examples of high-tech camping gear – capable of housing small groups of people on the vertical sides of cliffs, as if bolted into the sky – begin to look like something dreamed up by Archigram: nomadic, modular, and easy to assemble even in wildly non-urban circumstances. This is tactical gear for the spatial expansion of private leisure.

There are about a million implications here – including, at the very least, the question of whether or not architects should be involved in designing tents for North Face or for REI. If Zaha Hadid can design desk lamps and Frank Gehry, jewelry – and Michael Graves, teapots – then why can't, say, Jean Nouvel design a new series of outdoor recreational equipment, including tents, portaledges, platforms, and hammocks?

In fact, Jonathan Olivares, the author of the piece, describes the invention of the portaledge as follows: "Drawing from hammocks, cots, tents and sail construction, a generation of climber-designers invented a new typology: the portaledge." As such, the portaledge already has a fascinating design genealogy – one that includes the B.A.T. tent, the LURP, so-called "Cliff Dwellings" equipment, and tube-framed, waterproof tepees – but get some architects involved with this and see what happens.

Unless, of course, this is yet another case where architects have fallen behind the other design fields, too obsessed with accurately quoting Gilles Deleuze to notice that the world has been revolutionized. All sorts of amazing new tools, techniques, materials, shapes, and spaces were being framed and even mass-manufactured out there, for decades, but architects were all cooped up, underlining things for each other in the library.

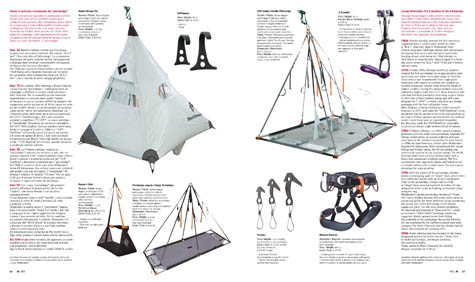

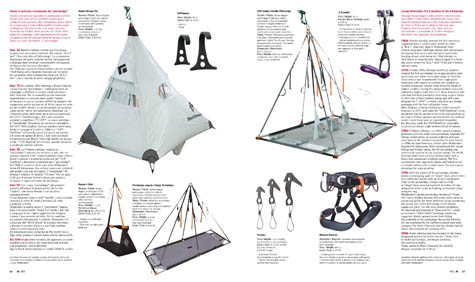

[Image: Another spread from Abitare, an article by Jonathan Olivares; view larger!].

[Image: Another spread from Abitare, an article by Jonathan Olivares; view larger!].

In any case, I suppose one could say that this tent, below, the Dyad 22 by North Face, looks vaguely like some sort of microlight architectural folly designed by Neil Denari for the beaches of Southern California –

[Image: The Dyad 22 by North Face].

[Image: The Dyad 22 by North Face].

– and these tents, the Domes 5 and 8, also by North Face, look like, say, Buckminster Fuller in collaboration with Shigeru Ban. Or: if Buckminster Fuller and Shigeru Ban came together to franchise the design of London's Serpentine Pavilion one summer, perhaps this is what they would make.

Leading to the question: are tents an example of franchise architecture?

[Image: The Dome 5 and Dome 8 by North Face].

[Image: The Dome 5 and Dome 8 by North Face].

So why aren't architects involved, as far as I'm aware, in the portable, modular architecture market known as high-end camping gear?

You ascend to the top of Mt. Everest... sleeping in a tent by Greg Lynn. Your sleeping bag is by OMA. Your best friend is comfortably slumbering beside you in a tent designed by LOT-EK.

[Images: Two spreads from Abitare; view larger: top and bottom].

[Images: Two spreads from Abitare; view larger: top and bottom].

But Abitare's article also implies something like the opposite of what I've written above: in other words, if high-tech camping gear used for vertical mountain ascents is actually a form of architectural technology, and thus worthy of being covered and critiqued by architecture magazines, then architects themselves should find more uses for such gear in their designs.

Rather than design camping gear, then, they should design with camping gear, filling private homes and office high-rises with unexpected tent-like rooms and rapidly deployed nylon conference facilities. You carry your boardroom around in your briefcase, installing it up on the roof when summer allows.

Or, perhaps, you construct a 21-story bare steel frame somewhere on an empty lot in New York City. It has no walls or floors; it is just a vast and abstract grid of I-beams, welded throughout with anchorage points. Using portaledges and tents, the inhabitants of this empty frame, like people from a fever dream by Yona Friedman or Constant, come in and colonize the structure, installing themselves at odd angles with carabiners and clips, bungee cords and tactical ropes, paying rent only on the spatial volume that the resulting structures occupy. $10 per cubic foot.

The grid – the structure – is taken care of. Architecture becomes nothing but the process of designing better tents. Flexible interiors. Sewn space.

So is high-tech 21st century camping gear exactly what the 1960s architectural avant-garde had been looking for? The portaledge as vertical utopia.

[Image: Spatial City by Yona Friedman: "The framework was to be erected first, and the residences conceived and built by the inhabitants inserted into the voids of the structure." Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art].

[Image: Spatial City by Yona Friedman: "The framework was to be erected first, and the residences conceived and built by the inhabitants inserted into the voids of the structure." Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art].

To a certain extent, though, this reminds me of my experience just last week as a judge for the Design Village 2008: Mission to Mars competition, photographs of which can be found here. With some obvious exceptions, that contest gave us the tent as avant-garde – and even extra-planetary – architecture. In one case, it was the tent as full-fledged micronation, flirting with new definitions of political sovereignty.

Perhaps 2009 will be the year tent design explodes across architecture schools, worldwide.

Given zero insurance liability, then, could you arrange for a new, annual architecture competition, sponsored by REI, the point of which is to ascend Yosemite's Half Dome or El Capitan using only home-made, microlight portaledge technology? If you fall, you lose. You have to make it to the top within seven days – and you have to stay there for another three.

Then you have to make it back down.

[Image: From Abitare; view larger].

[Image: From Abitare; view larger].

All these instant cities of tents and portaledges, moving up and down mountainsides around the world, like Walking Cities, the urban condition gone nomadic – the new, vertical suburb, till now so architecturally underexplored.

(Original articles curated by Anniina Koivu. With huge thanks to Fabrizio Gallanti from Abitare for emailing me the page spreads!)

[Image: From an article by Jonathan Olivares, in Abitare; view much larger!].

[Image: From an article by Jonathan Olivares, in Abitare; view much larger!].Viewed architecturally, these examples of high-tech camping gear – capable of housing small groups of people on the vertical sides of cliffs, as if bolted into the sky – begin to look like something dreamed up by Archigram: nomadic, modular, and easy to assemble even in wildly non-urban circumstances. This is tactical gear for the spatial expansion of private leisure.

There are about a million implications here – including, at the very least, the question of whether or not architects should be involved in designing tents for North Face or for REI. If Zaha Hadid can design desk lamps and Frank Gehry, jewelry – and Michael Graves, teapots – then why can't, say, Jean Nouvel design a new series of outdoor recreational equipment, including tents, portaledges, platforms, and hammocks?

In fact, Jonathan Olivares, the author of the piece, describes the invention of the portaledge as follows: "Drawing from hammocks, cots, tents and sail construction, a generation of climber-designers invented a new typology: the portaledge." As such, the portaledge already has a fascinating design genealogy – one that includes the B.A.T. tent, the LURP, so-called "Cliff Dwellings" equipment, and tube-framed, waterproof tepees – but get some architects involved with this and see what happens.

Unless, of course, this is yet another case where architects have fallen behind the other design fields, too obsessed with accurately quoting Gilles Deleuze to notice that the world has been revolutionized. All sorts of amazing new tools, techniques, materials, shapes, and spaces were being framed and even mass-manufactured out there, for decades, but architects were all cooped up, underlining things for each other in the library.

[Image: Another spread from Abitare, an article by Jonathan Olivares; view larger!].

[Image: Another spread from Abitare, an article by Jonathan Olivares; view larger!].In any case, I suppose one could say that this tent, below, the Dyad 22 by North Face, looks vaguely like some sort of microlight architectural folly designed by Neil Denari for the beaches of Southern California –

[Image: The Dyad 22 by North Face].

[Image: The Dyad 22 by North Face].– and these tents, the Domes 5 and 8, also by North Face, look like, say, Buckminster Fuller in collaboration with Shigeru Ban. Or: if Buckminster Fuller and Shigeru Ban came together to franchise the design of London's Serpentine Pavilion one summer, perhaps this is what they would make.

Leading to the question: are tents an example of franchise architecture?

[Image: The Dome 5 and Dome 8 by North Face].

[Image: The Dome 5 and Dome 8 by North Face].So why aren't architects involved, as far as I'm aware, in the portable, modular architecture market known as high-end camping gear?

You ascend to the top of Mt. Everest... sleeping in a tent by Greg Lynn. Your sleeping bag is by OMA. Your best friend is comfortably slumbering beside you in a tent designed by LOT-EK.

[Images: Two spreads from Abitare; view larger: top and bottom].

[Images: Two spreads from Abitare; view larger: top and bottom].But Abitare's article also implies something like the opposite of what I've written above: in other words, if high-tech camping gear used for vertical mountain ascents is actually a form of architectural technology, and thus worthy of being covered and critiqued by architecture magazines, then architects themselves should find more uses for such gear in their designs.

Rather than design camping gear, then, they should design with camping gear, filling private homes and office high-rises with unexpected tent-like rooms and rapidly deployed nylon conference facilities. You carry your boardroom around in your briefcase, installing it up on the roof when summer allows.

Or, perhaps, you construct a 21-story bare steel frame somewhere on an empty lot in New York City. It has no walls or floors; it is just a vast and abstract grid of I-beams, welded throughout with anchorage points. Using portaledges and tents, the inhabitants of this empty frame, like people from a fever dream by Yona Friedman or Constant, come in and colonize the structure, installing themselves at odd angles with carabiners and clips, bungee cords and tactical ropes, paying rent only on the spatial volume that the resulting structures occupy. $10 per cubic foot.

The grid – the structure – is taken care of. Architecture becomes nothing but the process of designing better tents. Flexible interiors. Sewn space.

So is high-tech 21st century camping gear exactly what the 1960s architectural avant-garde had been looking for? The portaledge as vertical utopia.

[Image: Spatial City by Yona Friedman: "The framework was to be erected first, and the residences conceived and built by the inhabitants inserted into the voids of the structure." Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art].

[Image: Spatial City by Yona Friedman: "The framework was to be erected first, and the residences conceived and built by the inhabitants inserted into the voids of the structure." Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art].To a certain extent, though, this reminds me of my experience just last week as a judge for the Design Village 2008: Mission to Mars competition, photographs of which can be found here. With some obvious exceptions, that contest gave us the tent as avant-garde – and even extra-planetary – architecture. In one case, it was the tent as full-fledged micronation, flirting with new definitions of political sovereignty.

Perhaps 2009 will be the year tent design explodes across architecture schools, worldwide.

Given zero insurance liability, then, could you arrange for a new, annual architecture competition, sponsored by REI, the point of which is to ascend Yosemite's Half Dome or El Capitan using only home-made, microlight portaledge technology? If you fall, you lose. You have to make it to the top within seven days – and you have to stay there for another three.

Then you have to make it back down.

[Image: From Abitare; view larger].

[Image: From Abitare; view larger].All these instant cities of tents and portaledges, moving up and down mountainsides around the world, like Walking Cities, the urban condition gone nomadic – the new, vertical suburb, till now so architecturally underexplored.

(Original articles curated by Anniina Koivu. With huge thanks to Fabrizio Gallanti from Abitare for emailing me the page spreads!)

Comments are moderated.

If it's not spam, it will appear here shortly!

Personally, knowing how big-name architects and designers' stuff I see tends to be avant-garde-looking but unusable and overpriced, the last thing I'd want them near is gear that has to keep me alive. I'd be nervous that the architect who's never climbed anything higher than the stairway to their beach house decided to take out crucial load bearing framework hardware because they 'interfered with the line' of the 'statement' they were trying to make with the 'deconstruction' of my portaledge, and thus the "statement" made is me plummeting to my death in the middle of the night -G

I'm a student at Bergen School of Architecture in Norway and here, designing a tent is actually the first task we are given as a fresh student.

The first month of the study you are staying on a small island outside the cost called Utsira. It's a windy and quite extreme environment in the middle of the ocean. There the students spend a month living in tents to get to know the basics of why we build houses.

After the month, when we return to the school. The first task is to plan "a house which is not a house, a tent that is not a tent". A portable construction that is to be used for a half year out on the same island you stayed at.

There are quite a few interesting tent approaches that comes up. I planed a rhombic triacontahedron, module based construction. It's a really fun and nice task to give fresh students.

Martin, that sounds really cool, actually - do you have any photos? Or drawings?

I believe that Taliesin West used to start their students in a tent.

Yes I do!

Here are two pictures from the model of my "tent" http://flickr.com/search/?w=72687467%40N00&q=arne&m=tags

It's nice to look back at that task now, almost a year later. I would have changed a lot of things now, lookin back, but I quite like my basic idea of square building elements that put togeather makes a shelter.

And there are a few images of the trip as well. Mostly just my group hanging arround and doing registrations and other day to day activities. http://flickr.com/photos/blomstereng/sets/72157602307661001/

Randolph's right. I visited Taliesin West in November and they still require students to live in either tents or some other outdoor structure. One of their final projects is to design their own structure to live in for what I believe is their final semester. Its obviously not on the side of a cliff, but there are snakes and scorpions to keep in mind during the designing.

I'd imagine staying in one of these cliffside things is horrifying if you sleepwalk.

It's interesting how you insist that architecture be used rather than design. I'm aware of the distinction, (I'm an industrial designer myself). A collaboration of the two, would likely be the best option, but the point is the designer/architect used simply need be familiar with the design topic and materials involved(as in any redesign of existing spaces or products). Just because you have a "space designing" hammer doesn't always mean,, "use hammer". Just like an architect is always better, or a product designer is always better. I know plenty of product designers that develop spaces well, and architects that make products well. Don't let your biases of initial learning (or simply the name architect) get in the way of an excellent solution (some of the existing port-a-ledges are quite nice and do a very good job with the myriad constraints they face. As designers and architects we all attend classes and constantly re-educate our selves to quite a degree.

Additionally, I love the School project Martin,, it looks like a heck of a lot of fun!

I like your porta-ledge design contest idea (it would be neat). However, the "living in it" side of the contest wouldn't be so wonderful, (if you want to do that, let the distance be 1 meter over foam, it's reasonable and still provides a hint of fun). It would be interesting at schools with both industrial designers and architects to have each group compete with each other, then to collaborate for a second try, what a difference!

Thanks for the discussion promoting article!

Ambivalence. So cool to see people figuring out ways to do things like live on a cliff face. But also unnerving to think about the exclusivity of those activities, or of how they might get translated into mass urban activities.

What would it cost to make a permanent residence in this style? What does it cost to make a minimalist housing solution that performs well in extreme conditions? Is cost a factor in explaining why this method of habitation has not been widely adopted aeons ago?

Transposing the idea to urban environments, where would people hang their platforms, and where do people currently go climbing?

Let's suppose that people start hanging these things off towers, living like tree squatters on the sides of used and disused buildings, highway supports, bridges, even buses and trains. What then if designers start producing alternative motorhomes with fold-out features. Pop-up urban camping? A solution for commuters?

i used to do lots of camping and loved living in a tent. oddly enough i don't think that i have done any camping since i transfered to architecture school about a decade ago.

and bergen, norway is a lovely city...i wouldn't mind living in a tent there.

I sent your post to a friend who founded one of the leading outdoor equipment companies. If it's a subject that continues to interest you, he's Bay Area-based.

Here's part of his response:

Yes, tents are architecture. I have a couple tents that I designed in the Los Angeles Museum of Modern Art, even some posters were made that displayed them as such there. I have another tent that I designed that was put in one of those coffee table books called, “Made in America” which touted things that were very artistic that were successful and made in America. Classic designs, supposedly. I don’t know if I would have architects designing tents, unless that is they knew a lot about the forces there. We spent a week every year for years up on Mount Washington, studying wind and weather on tents. We spent this during December most every year when we could be guaranteed of winds in excess of 100 miles per hour for days. (often up to 130 or more miles per hour for 12 hours in a row) That type of study is important, to be able to attach monitors to poles and fabrics all over the tent and measure the stress/strain on such in winds. To also set tents up in such conditions. Might seem like a great tent once set up, but for instance, the North Face dome tent below is notoriously bad to set up in winds. We actually took up 75 competitors tents one year and tried setting them up. We ripped many apart well before they were erected. This was done not to show nasty videos of their problems, but to learn about the problems, to compare them with our own, see if there were things that were better. (The TNF dome could NOT be set up in 70 mile an hour winds unless you had about 10 people to help, and even then you stood a good chance of destroying the tent.)

Geoff says: "So why aren't architects involved, as far as I'm aware, in the portable, modular architecture market known as high-end camping gear?"

Because architects aren't climbers. Climbers only trust climbers with their lives. You know? When you're 300m above a solid granite valley floor hanging from a cliff face by a couple carabiners and some nylon rope, you only care that you don't die due to poor design.

And really... We all love to see some audacious architecture from time to time, but there's always some guy who has to figure out where to route the sewage pipes through all the postmodern intricacies. And that guy can relate to the climbers' choice of design.

Speaking of Yona Friedmann... His Ville Spatiale was created in Second Life, and people inhabited it and did just what you're saying. The financials were handled in much the way you describe. Here's a bit about me moving in...

The Ville was demolished a few weeks back, in favor of another experimental design. Come see. :-)

Architect/Climber voting 08' for a Porta-Ledge design contest and Yosemite adventure. In the spring of 2003, I developed and constructed a prototype ledge while in architecture school -

Sheer Mobility: A Portable Shelter for Vertical Environments.

It was an exploration that continues to inspire to this day.

You'll probably all have a right go at me but I'm just going to put this out there - I have always seen the tent as not architecture but an extension of the clothes you are wearing or perhaps an extension of a sleeping bag. I don't know why but purchasing a tent I approached it more like this than buying real estate.

Fascinating subject though.

I find good tent designs to be strikingly beautiful. However, their aesthetic qualities are by-products of function. The ultimate purpose of any backpacking shelter is maximum function with minimum weight.

For examples: Gossamer Gear's The One (http://www.gossamergear.com/cgi-bin/gossamergear/The_One.html), TarpTents from Henry Shires (http://tarptent.com/products.html), solutions from Six Moon Designs (http://sixmoondesigns.com/shop/shopdisplayproducts.asp?id=11&cat=Shelters), and items from Mountain Laurel Designs (http://mldgear.com/shop/index.php).

great post boys!

I was a climber/camper long before I went to architecture school, and would be thrilled to land a gig doing tents and portaledges after I'm done. I recently took up sailing and more recently picked up an awesome stunt kite- which seems to be sailing, tenting, and architecture all in one. I find this overlap thrilling and am ecstatic to see this article. Geoff- you sure know how to pick 'em.

kp

"Personally, knowing how big-name architects and designers' stuff I see tends to be avant-garde-looking but unusable and overpriced, the last thing I'd want them near is gear that has to keep me alive."

Anonymous isn't the only one to voice this fear. And yet people are prepared to go inside their (often quite tall) buildings without a fear that a wall is going to topple on them any time soon.

Architects are used to the concept that getting things wrong means people die, so I don't see why this should be any different, as long as they remember it's a proper structure, not an interesting-looking teapot.

Spine Architects here in Hamburg have sort of an annoying website, but if you scroll down to the middle you'll find their Wohnplakat. It's a cliff tent you attach to a billboard, so all of your expenses are paid by the advertiser.

http://www.spine-architects.com/work/concepts.html

@iain - I understand your point but a tent/portaledge does not need to fall off a cliff to kill a climber. Leaking (MIT/Gehry/Stata) or getting the weight/durability trade off wrong will do as well. When you are operating this close to the edge, direct experience is important - not surprisingly, climbers do most of the designing and making. There's also the fact that the niche is vanishingly small - nobody else cares *grin*.

Perhaps a more succinct way to put is that our punch list is a climber's body bag.

I think there are some more subtle personality issues being missed here.

Most climbers are outdoors people. They use tents for protection from weather. They could care less that architects even exist, and the names dropped on this page are static to them. They care only about functionality of the tools. Aesthetics are a bonus, if that.

But look at what the commenters have said about tents. Students use them, and the implication in the comments is that one should try to design tents to help them escape the outdoors. Live in a tent to see why houses are built?? Are you on crack? Houses only exist to sit out the winter until the snow has melted in the mountains again. Houses are the temporary structures.

I'm sure an architect could build cool tents that are perfectly safe.

I'm just not so sure that anyone who uses the tents would give a bleep.

As somebody who makes his living designing and manufacturing gear for climbers, I found this posting interesting and a wee bit scary. My parents are both architects, and I did grow up with, uh, architectural building blocks and toys.

There is a significant difference between somebody with a known brand (Gehry, Graves, Hadid) doing a conceptual design for profit and designing life support machinery and equipment. In the comments section, Iain mentioned that "architects are used to the concept that getting things wrong means people die" yet that ignores the immense body of building code, the work of structural engineers and other non-architects in creating safe structures. Does anyone really believe that the architect did the UL certification process for any lamp, branded by a famous architect or not? I might be in error, but I suspect that the skyscrapers of Manhattan are designed by architects and engineered by civil and structural engineers.

In the world of portaledges, there has been limited interaction between designers and engineers: historically, the designers of the ledges were engineers or physicists who could perform the requisite finite element analysis before testing their designs in the harsh reality of the world. As Dr Hypercube says, many of the common faults found in the work of high end architects would result in a high death toll. Leaks can be fatal.

However, I agree to a point with Fred's comment that the label the person has doesn't matter if they're willing to get down and dirty in the details, the testing and the process. It could be interesting. I think they'd have to come with a large chunk of humble pie: read the interview in the article with john middendorf, and consider his resume. As discussed in the Arbitare article, the amount of work already done on portaledges is not trivial. Of course, there is room for improvements, but the current ledges reflect thousands of hours of work, consideration, experiment and modeling. Think of those long winter months sitting on top of Mt. Washington -- those months and the empirical results are legendary in the business. They are probably up there with the empirical results of Adidas on sports specific engineering in terms of the granularity of the research and the broad spectrum of the applicability of the results.

As for the contest, good luck! About 60% of people fail on their first attempt on a big wall. The number of routes that absolute gumbies would be able to do on El Cap is relatively limited, so there would be a traffic jam. The average first time party needs four or five days to get up. There is no water on top of El Cap.

All in all, I give my thanks to BldgBlog for an interesting discussion of the world I work in viewed from an outsider's perspective.

I don't mean to be a stuffy old poop, but those tents hanging from the rock face, and particularly that platform with the two loungers image, really offend me. These might be wellsprings of architectural inspiration, but they feel crass to me... something about that much materialism where nature has always reigned.... Whatever ideas you get, don't let them capture that aspect please.

"Unless, of course, this is yet another case where architects have fallen behind the other design fields, too obsessed with accurately quoting Gilles Deleuze to notice that the world has been revolutionized. All sorts of amazing new tools, techniques, materials, shapes, and spaces were being framed and even mass-manufactured out there, for decades, but architects were all cooped up, underlining things for each other in the library."

If I was to believe this statement in addition to the contributed comments, I could almost fool myself in believing that architects are the bookish indoors type who carry around a T-square and a clutch pencil at all times, and on their relaxing weekends they retreat to their delightful little beach shack. Sounds smashing. The only problem is, the real world of architects and the industry they work in is generally so far flung from this stereotype that it's laughable that both this blog and commenters are still clinging to either the notion of all architects as indoor gentleman types or the notion of architecture being even remotely close to a glamourous profession. Sure, the "big" names might have a little more glamour in their lives, but how many "big name" architects can you name off the top of your head? Then consider how many architects there are in the world. Architecture, and architects, are not all like Gehry and Hadid. And whilst these names can obviously pull some weight where it's needed (especially when it comes to marketing), it's very short-sighted to suggest that these few people are the only measure of architecture and architects alike.

Also, to suggest that architecture is constantly falling behind other design fields probably reflects the business end of the industry well, where the economics of scale clearly impact on a building moreso than a handheld item for example (fairly obviously if you ask me), but nevertheless, don't apply this blanket statement across the board as architecture is far more than just the big name offices everyone here seems to know (and care?) about. Schools of architecture around the world continue to push boundaries, question status quo and take the risks that many businesses simply can't afford to take. This is without even mentioned the innumerable research and development collaborations between architecture schools, manufacturing companies, government departments and architectural firms, so it might be worthwhile considering that there's a little more to architecture than the pigeonhole most people seem so keen to force it into.

How about an architecture of ascending consciousness?

By simply tilting a box, a vertical vector is created to the infinite real estate above, diminishing want of the limited lateral so that we might live in smaller, less consuming, and higher quality spaces.

Post a Comment