The Other Night Sky

Every once and a while there's a flash in the sky, lasting roughly twenty seconds, and – provided you look into these things in advance – you can accurately predict when the flash is coming. It's thus possible to be there when it happens.

You can point up at the sky for amazed friends, saying watch this – and a light appears, way up above you, beyond even where airplanes fly.

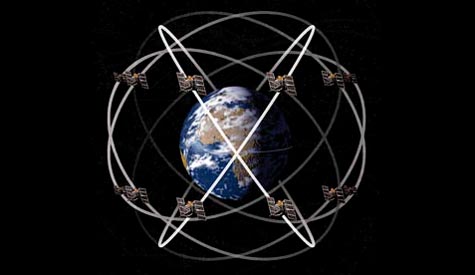

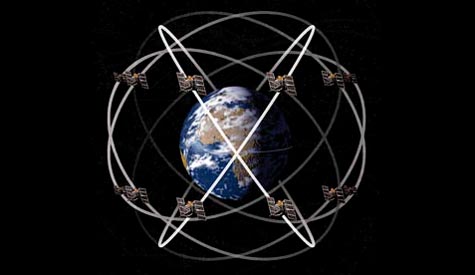

What's passing overhead in this instance is something called the Iridium constellation, an artificial pattern made of 66 telecom satellites (there were supposed to be 77, which would have corresponded with the number of electrons in an atom of iridium).

What's passing overhead in this instance is something called the Iridium constellation, an artificial pattern made of 66 telecom satellites (there were supposed to be 77, which would have corresponded with the number of electrons in an atom of iridium).

The whole thing was sold less than a decade ago for a mere $25 million to private investors – after being launched and constructed, in the 1980s, at a price of nearly $6 billion.

The company that initially sponsored the project went bankrupt in 1999 – raising the prospect, like something from Greek mythology as rewritten by Philip K. Dick, or perhaps something out of Arthur C. Clarke as rewritten by Homer, that our sky will someday be full of artificial constellations, their human creators having long since disappeared. Cold, dead objects, they'll encircle the world in silence.

The company that initially sponsored the project went bankrupt in 1999 – raising the prospect, like something from Greek mythology as rewritten by Philip K. Dick, or perhaps something out of Arthur C. Clarke as rewritten by Homer, that our sky will someday be full of artificial constellations, their human creators having long since disappeared. Cold, dead objects, they'll encircle the world in silence.

Along these lines, a new exhibition of photographs by geographer Trevor Paglen opens here in the Bay Area next week, called The Other Night Sky. The Other Night Sky "looks to the night sky as a place of covert activity," we read:

Along these lines, a new exhibition of photographs by geographer Trevor Paglen opens here in the Bay Area next week, called The Other Night Sky. The Other Night Sky "looks to the night sky as a place of covert activity," we read:

It genuinely amazes me to think that, 45,000 years ago, groups of cognitively modern humans were wandering around Australia and the Middle East and Africa and South Asia, and they were looking up at and navigating themselves by recognizable patterns in the sky – but, now, we can just install our own stars there and guide ourselves by them, instead.

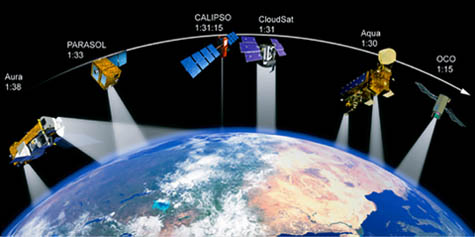

[Image: The International Space Station, from a series of photos by Dirk Ewers].

[Image: The International Space Station, from a series of photos by Dirk Ewers].

We are now partially building ourselves a new night sky – yet this surrogate astronomy is being put there simply so we can spy each other and make international phone calls.

In some ways, I'm reminded of a line from Richard Kenney's 1993 book of poetry The Invention of the Zero. At one point, Kenney writes: "Imagine, all new constellations!" as if it is some impossible, heroic act of celestial reinvention yet to occur in human history.

In some ways, I'm reminded of a line from Richard Kenney's 1993 book of poetry The Invention of the Zero. At one point, Kenney writes: "Imagine, all new constellations!" as if it is some impossible, heroic act of celestial reinvention yet to occur in human history.

But the weird irony of life is that we've already done that – and we didn't overthrow the astronomers, or plan a coup in the planetarium of human thought, we just launched some telecom satellites and bought a bunch of mobile phones, and now we have it: we have new constellations – what Kenney calls "unfamiliar skies" – flashing through the night at timed intervals.

In any case, I've been tracking these constellations on a little Applet today – but there's a certain sinister side to all of this, too. Space warfare, we read, is the militarization of the earth's high atmosphere, weaponizing low-orbit space. You can thus strike anyplace on the earth within mere minutes of ordering an attack – including the infamous "rods from god," which are non-explosive tungsten rods dropped from extremely high altitude:

In any case, I've been tracking these constellations on a little Applet today – but there's a certain sinister side to all of this, too. Space warfare, we read, is the militarization of the earth's high atmosphere, weaponizing low-orbit space. You can thus strike anyplace on the earth within mere minutes of ordering an attack – including the infamous "rods from god," which are non-explosive tungsten rods dropped from extremely high altitude:

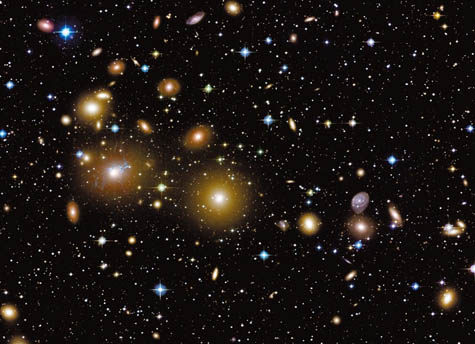

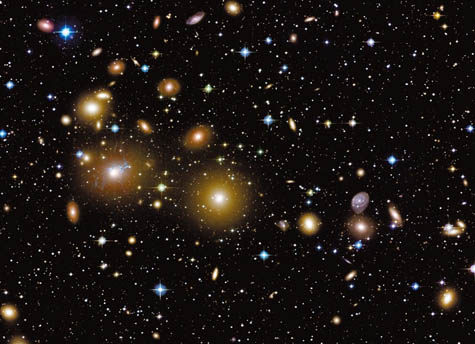

[Image: The Perseus Cluster, photographed by Jean-Charles Cuillandre & Giovanni Anselmi].

[Image: The Perseus Cluster, photographed by Jean-Charles Cuillandre & Giovanni Anselmi].

And what would we do if we found out that Orion, say, or the Southern Cross, was not a natural constellation at all, but something placed there, installed above us, in our imaginations, in our myths?

(Trevor Paglen's The Other Night Sky, from which this post's title was taken, opens June 1st at the Berkeley Art Museum).

You can point up at the sky for amazed friends, saying watch this – and a light appears, way up above you, beyond even where airplanes fly.

What's passing overhead in this instance is something called the Iridium constellation, an artificial pattern made of 66 telecom satellites (there were supposed to be 77, which would have corresponded with the number of electrons in an atom of iridium).

What's passing overhead in this instance is something called the Iridium constellation, an artificial pattern made of 66 telecom satellites (there were supposed to be 77, which would have corresponded with the number of electrons in an atom of iridium). The whole thing was sold less than a decade ago for a mere $25 million to private investors – after being launched and constructed, in the 1980s, at a price of nearly $6 billion.

The company that initially sponsored the project went bankrupt in 1999 – raising the prospect, like something from Greek mythology as rewritten by Philip K. Dick, or perhaps something out of Arthur C. Clarke as rewritten by Homer, that our sky will someday be full of artificial constellations, their human creators having long since disappeared. Cold, dead objects, they'll encircle the world in silence.

The company that initially sponsored the project went bankrupt in 1999 – raising the prospect, like something from Greek mythology as rewritten by Philip K. Dick, or perhaps something out of Arthur C. Clarke as rewritten by Homer, that our sky will someday be full of artificial constellations, their human creators having long since disappeared. Cold, dead objects, they'll encircle the world in silence.  Along these lines, a new exhibition of photographs by geographer Trevor Paglen opens here in the Bay Area next week, called The Other Night Sky. The Other Night Sky "looks to the night sky as a place of covert activity," we read:

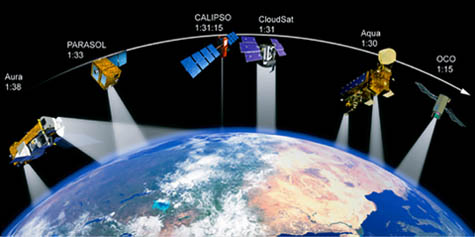

Along these lines, a new exhibition of photographs by geographer Trevor Paglen opens here in the Bay Area next week, called The Other Night Sky. The Other Night Sky "looks to the night sky as a place of covert activity," we read:[W]orking with data compiled by amateur astronomers and hobbyist “satellite observers,” cross-referenced across many sources of information, [Paglen] tracks and presents what he calls “the other night sky.” Large-scale astro-photographs isolate barely perceptible traces of surveillance vessels amidst familiar star fields, and a digitally animated projection installation covers the globe with 189 currently orbiting satellites.In other words, Paglen has been tracking surveillance satellites – false stars that would otherwise have blended in with astronomy.

It genuinely amazes me to think that, 45,000 years ago, groups of cognitively modern humans were wandering around Australia and the Middle East and Africa and South Asia, and they were looking up at and navigating themselves by recognizable patterns in the sky – but, now, we can just install our own stars there and guide ourselves by them, instead.

[Image: The International Space Station, from a series of photos by Dirk Ewers].

[Image: The International Space Station, from a series of photos by Dirk Ewers].We are now partially building ourselves a new night sky – yet this surrogate astronomy is being put there simply so we can spy each other and make international phone calls.

In some ways, I'm reminded of a line from Richard Kenney's 1993 book of poetry The Invention of the Zero. At one point, Kenney writes: "Imagine, all new constellations!" as if it is some impossible, heroic act of celestial reinvention yet to occur in human history.

In some ways, I'm reminded of a line from Richard Kenney's 1993 book of poetry The Invention of the Zero. At one point, Kenney writes: "Imagine, all new constellations!" as if it is some impossible, heroic act of celestial reinvention yet to occur in human history.But the weird irony of life is that we've already done that – and we didn't overthrow the astronomers, or plan a coup in the planetarium of human thought, we just launched some telecom satellites and bought a bunch of mobile phones, and now we have it: we have new constellations – what Kenney calls "unfamiliar skies" – flashing through the night at timed intervals.

In any case, I've been tracking these constellations on a little Applet today – but there's a certain sinister side to all of this, too. Space warfare, we read, is the militarization of the earth's high atmosphere, weaponizing low-orbit space. You can thus strike anyplace on the earth within mere minutes of ordering an attack – including the infamous "rods from god," which are non-explosive tungsten rods dropped from extremely high altitude:

In any case, I've been tracking these constellations on a little Applet today – but there's a certain sinister side to all of this, too. Space warfare, we read, is the militarization of the earth's high atmosphere, weaponizing low-orbit space. You can thus strike anyplace on the earth within mere minutes of ordering an attack – including the infamous "rods from god," which are non-explosive tungsten rods dropped from extremely high altitude: These rods, which could be dropped on a target with as little as 15 minutes notice, would enter the Earth's atmosphere at a speed of 36,000 feet per second – about as fast as a meteor. Upon impact, the rod would be capable of producing all the effects of an earth-penetrating nuclear weapon, without any of the radioactive fallout. This type of weapon relies on kinetic energy, rather than high-explosives, to generate destructive force.All these coordinated astronomical stand-ins – patterned groups of satellites moving around the world – thus might also someday serve as malign horoscopes of impending war. To what zodiac would such military constellations correspond? What defensive measures might a person take when a strange metallic glint appears in the evening sky, a 20-second flash on the horizon?

[Image: The Perseus Cluster, photographed by Jean-Charles Cuillandre & Giovanni Anselmi].

[Image: The Perseus Cluster, photographed by Jean-Charles Cuillandre & Giovanni Anselmi].And what would we do if we found out that Orion, say, or the Southern Cross, was not a natural constellation at all, but something placed there, installed above us, in our imaginations, in our myths?

(Trevor Paglen's The Other Night Sky, from which this post's title was taken, opens June 1st at the Berkeley Art Museum).

Comments are moderated.

If it's not spam, it will appear here shortly!

Hey Geoff,

Slightly off topic but related - are you familiar with Dyson spheres? Physicist Freeman Dyson speculated that satellites orbiting a star could collect energy far more efficiently than we can here on earth.

Eventually you build enough of these satellites so that they are so close together that they form a kind of super structure - a dyson sphere. An enormous structure with a star at its core.

blent.

i love this blog... very nice

Gorgeous post!

I don't think cellphones use satellites, BTW, just transmission towers plugged into the landline network. Satellite phones do, I guess.

Iridium-brand satellite phones are used all the time in Antarctica. The U.S. NSF has a contract with Iridium through the Dept. of Defense, with maybe one of the most robust service plans in the world-$20,000 a year for a number of these phones to call anywhere in the world, from anywhere, with unlimited minutes. They worked pretty good in middle of nowhere in Antarctica.

Also clever how Iridium's "Big Dipper" logo speaks to the corporate astronomy discussed in this post.

The notion that everything is moving is sentimental and comforting for me: I first noticed my husband when he commented during a math symposium that even the atoms of which we're made have unlocatable centers. And swoosh, I fell in love.

Though sinkholes still scare me to death.

From Freud's 'Civilization and its Discontents': 'Man's observation of the great astronomical regularities not only furnished him with a model for introducing order into his life, but gave him the first points of departure for doing so.'

A new Deism: tired of the chaos of the lower beings, a remote Demi-urge spins the constellations into order, giving us our first glimpse of the possibilities of repetition, regulation, patterns...a new step in evolution begins.

In response to your last bit about the possible artificial genesis of Orion or the Southern Cross, you ought to read Alastair Reynolds. Particularly his Revelation Space series in which he posits that very thing.

I´ve had that idea myself that ex. orions belt is a huge cigarshaped object spinning on the long side to generate gravity. It seems theres exactly the same distance from the star to the right of the belt as the star to the left. And i´ve never seen a star behind the huge "cigar shaped object". The "belt" in Orions belt is actually a belt of lights switching so that the lights looks static as the three "stars". SO Orion is a huge spaceship, been there since... life came here and Orions belt is just a light belt designed to look like three static stars though its millions of lights turning on and of at the right time.

Maybe thats why the pyramids associate so much to Orions belt!!

PLease comment on facebook, David Brüel or mail baker2ndplatoon@hotmail.com

Post a Comment