Nuclear Urbanism

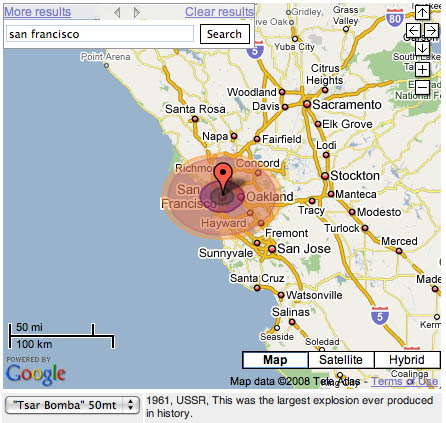

A Google Maps mash-up by Sydney-based design firm CarlosLabs has us looking at what nuclear explosions would do to cities all over the world.

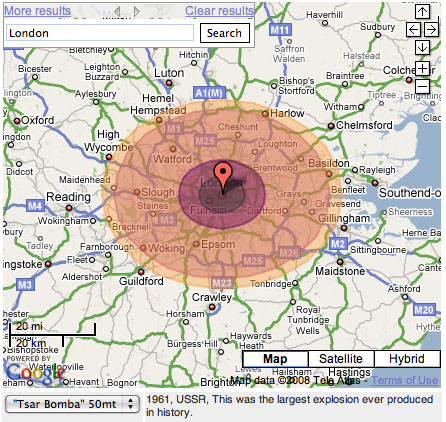

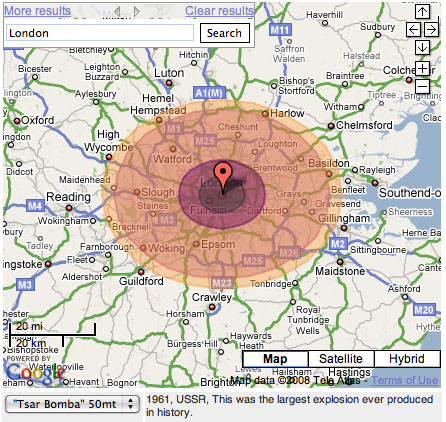

[Image: London nuked, courtesy of CarlosLabs].

[Image: London nuked, courtesy of CarlosLabs].

"This mapplet," we read, "shows the thermal damage caused by a nuclear explosion. Search for a place, pick a suitable weapon and press 'Nuke It!'"

The image you see above is London as decimated by an atomic bomb equivalent to the freakishly terrifying Soviet Tsar Bomba test of 1961. Everything as far as Guildford has been damaged – the entire center of the city simply gone.

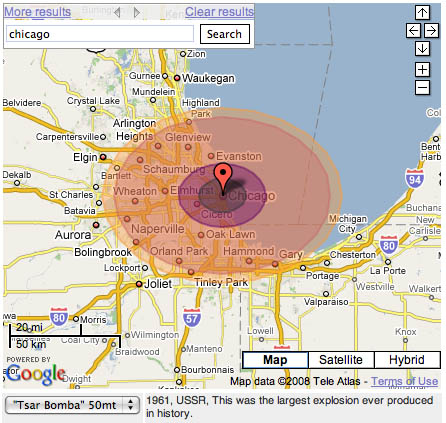

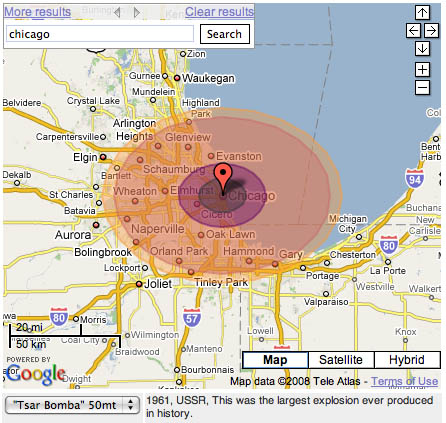

Below, we see Chicago obliterated by the same size of explosion. Looking closely, we see that the difference between a first- and second-degree burn – and this information is explained a bit more, below – passes directly through the distant suburban town in which I was born, Highland Park.

[Image: Courtesy of CarlosLabs].

[Image: Courtesy of CarlosLabs].

Waters along the shore of Lake Michigan would be instantly evaporated, forming radioactive rainstorms over northern Indiana, perhaps for days.

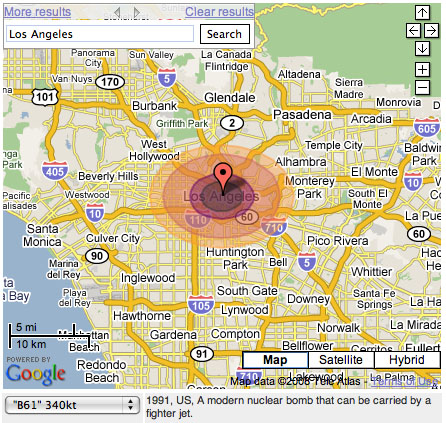

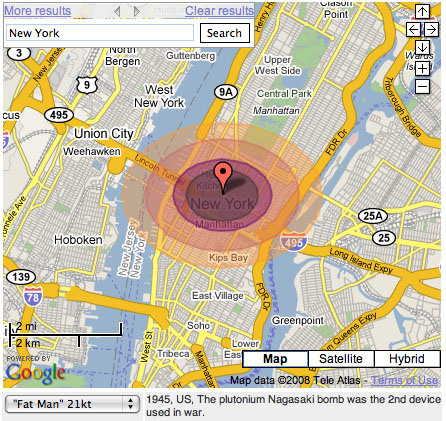

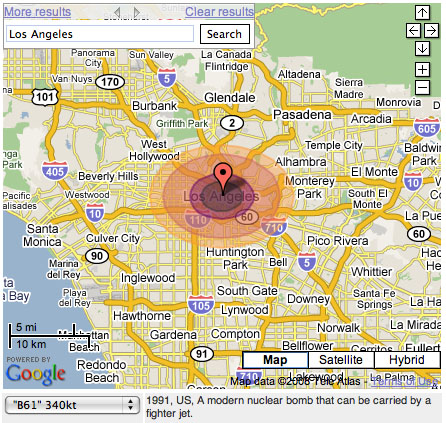

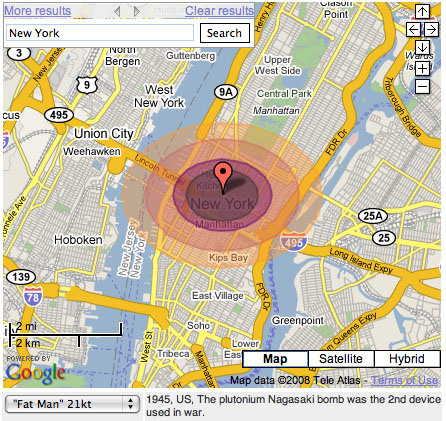

The size of the bomb can be varied, of course; here we see Los Angeles hit by any typical nuclear warhead carried by an American fighter jet, circa 1991; and, below that, we see New York City hit by a bomb equivalent to Fat Man, the device dropped on Nagasaki.

[Images: Courtesy of CarlosLabs].

[Images: Courtesy of CarlosLabs].

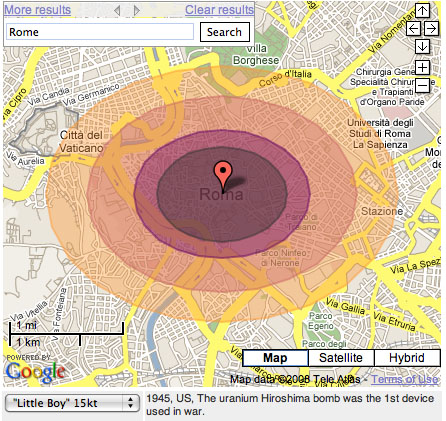

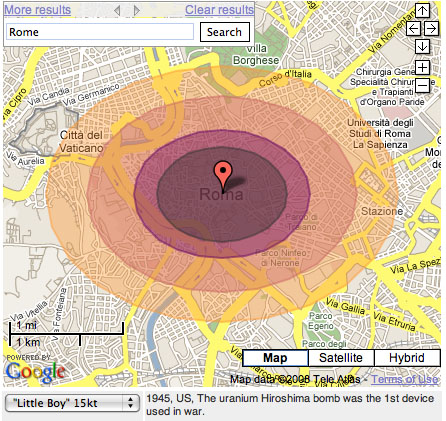

And here, below, is Rome hit by Little Boy, the bomb dropped on Hiroshima – and the first nuclear device ever used as an act of war.

If it's any consolation to Catholics – or architectural historians – the extreme, northwestern fringes of the Vatican would escape immediate harm.

[Image: Courtesy of CarlosLabs].

[Image: Courtesy of CarlosLabs].

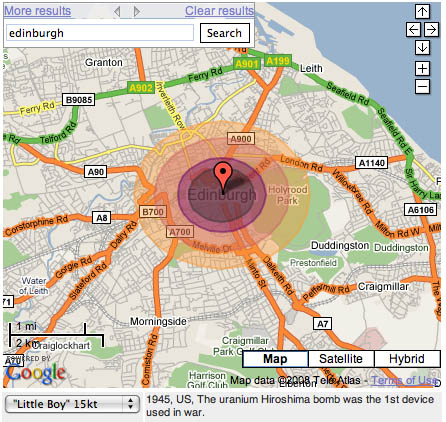

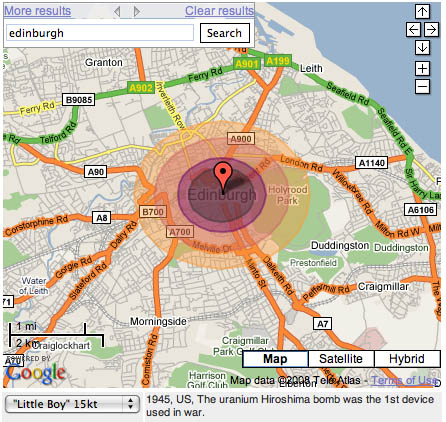

Alternatively, let's drop Little Boy on Edinburgh.

[Image: Courtesy of CarlosLabs].

[Image: Courtesy of CarlosLabs].

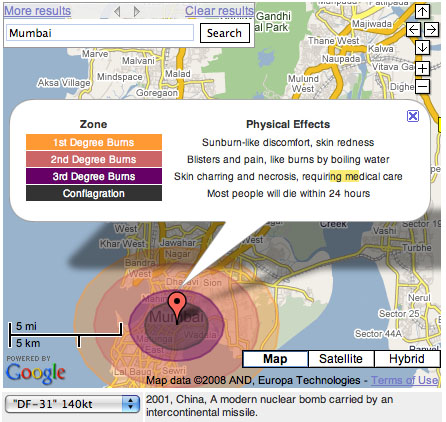

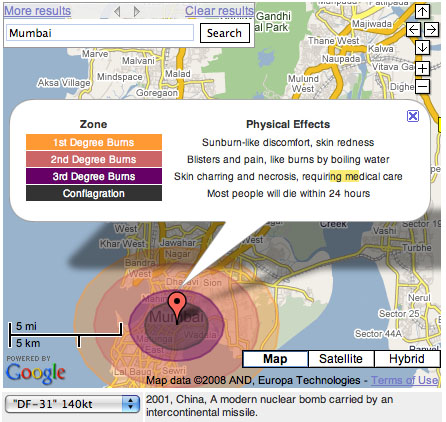

All of this is visually arresting – seeing vast bruises like bull's eyes consume whole cities – but what does it really mean? What is each colored circle supposed to represent?

In the following image of Mumbai being hit by a nuclear missile equivalent to those used by the Chinese military, we see concentric rings of 1st, 2nd, and 3rd degree burns expanding outward from the detonation – a geometry of necrosis, suffocation, and death. Blisters and cancer would affect tens of thousands of people for miles in every direction (depending on prevailing winds).

[Image: Courtesy of CarlosLabs].

[Image: Courtesy of CarlosLabs].

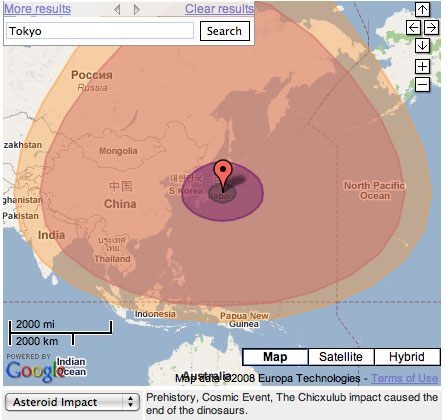

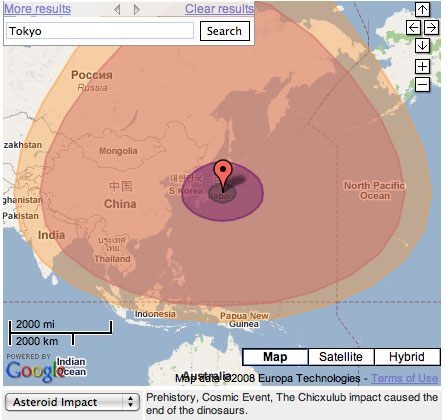

For some unexpected astronomical context, though, CarlosLabs has added a bizarre final option: seeing how asteroid impacts might compare with inter-urban nuclear war.

Tokyo – where the following image is centered – is not merely erased; struck by an asteroid, it's been placed at the heart of a planetary event, complete with rings of sunburn-equivalent injury spreading out across whole continents.

[Image: Courtesy of CarlosLabs].

[Image: Courtesy of CarlosLabs].

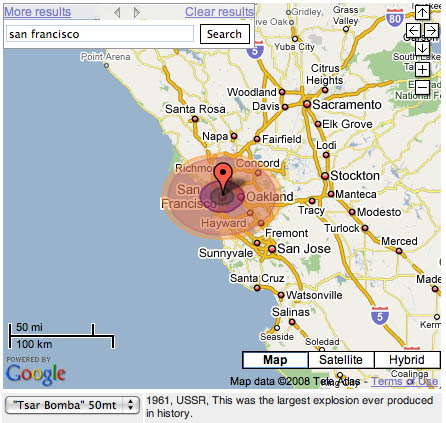

Returning to the realm of historical likelihood, the image that somehow clarifies this the most for me – if, for no other reason, because I live there – is the following glimpse of San Francisco. The entire peninsula has been blasted into absolute, smoking oblivion by an explosion equal to Tsar Bomba.

The fact that you would be more or less screwed as far south as Fremont – and well east of Oakland – seems sobering, indeed.

You could be sitting in the west-facing window of an Oakland high-rise, watching an atomic fireball explode over San Francisco – which quickly expands to melt the glass you're looking through.

[Image: Courtesy of CarlosLabs].

[Image: Courtesy of CarlosLabs].

A few quick points, meanwhile:

1) This will mean very little, and have no effect, but I am 100% behind complete nuclear disarmament. The U.S. taking the lead in this seems like something well worth pursuing.

2) In this context, I have to say that the books of Richard Rhodes cannot be recommended highly enough. His The Making of the Atomic Bomb – which I have to confess to having read only partially – is required reading for anyone interested in what intensive, well-funded efforts of design can – in this case, unfortunately – produce. The bomb as an act of national infrastructure.

3) Michael Light's book 100 Suns, a photographic survey of nuclear weapon tests, is as horrifying as it is visually spectacular, especially for anyone with an interest in human history (and its explosive intersection with enriched geology).

4) Gary Snyder has a great poem that I still think of now and again, 17 years after first reading it, called "Bomb Test." Originally written, I believe, in Kyoto in 1986, the poem presents nuclear weapons as a kind of new terrestrial element, something geologically unprecedented both in and on the surface of the earth – highly processed samples of mineral chemistry (uranium, plutonium) put into military service by rival superpowers.

"The fish float belly-up, for real," Snyder writes. "Uranium in the whites / of their eyes.

Even now, the globally nomadic residues of nuclear weapons tests form a ghostly stratigraphic marker that can be found literally around the world, an all but permanent part of the earth's sedimentary record.

So, in the images that illustrate this post, we see what effects this geological discovery – the explosive power of rare elements – could have on the built geography of our species.

Nuclear war thus poetically equates to hurling enriched fragments of the earth's surface at your rivals. Call it weaponized geology: minerals made altogether unearthly, if not post-terrestrial, through anthropological intervention.

5) Here is a random assortment of nuclear bomb photography. These were all Cold War-era tests – but, someday, perhaps soon, architects and architecture bloggers will be looking at similar images, images that have captured the obliteration of constructed environments from Mumbai or Karachi to New York, London, or Tehran. This will happen, I would say; it might well occur within our lifetimes, or at least within the next century; and any even partially accurate future assessment of global urbanism must still take nuclear weapons into account.

Nuclear weapons present us with a kind of demonic skeleton key, capable of catastrophically unlocking any city in the world, no matter how dense or well-fortified, in mere seconds.

Finally, here is what would happen if a nuclear bomb was dropped on a relatively non-urban environment: in this case, the town of Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

Finally, here is what would happen if a nuclear bomb was dropped on a relatively non-urban environment: in this case, the town of Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

[Image: Courtesy of CarlosLabs].

[Image: Courtesy of CarlosLabs].

But this could just as easily have been Ann Arbor, Santa Cruz, Austin, Shrewsbury, Castleton, Aberystwyth, Marburg – it could just as easily have been anywhere on earth.

The overwhelming obliterative power of nuclear weapons turns them into a kind of ubiquitous anti-landscape, something that no geography, built or natural, can successfully resist.

All of which is simply a long-winded way of saying that while we now tend to measure threats against our cities in terms of armed gangs or contextually minor moments of staged terrorist assault, it's still interesting to remember that, hovering over all of this, is something that could simply annihilate cities altogether.

If we're going to study cities, in other words, then we should also study that which is radically anti-city.

(Spotted via Alexis Madrigal and Wired Science).

[Image: London nuked, courtesy of CarlosLabs].

[Image: London nuked, courtesy of CarlosLabs]."This mapplet," we read, "shows the thermal damage caused by a nuclear explosion. Search for a place, pick a suitable weapon and press 'Nuke It!'"

The image you see above is London as decimated by an atomic bomb equivalent to the freakishly terrifying Soviet Tsar Bomba test of 1961. Everything as far as Guildford has been damaged – the entire center of the city simply gone.

Below, we see Chicago obliterated by the same size of explosion. Looking closely, we see that the difference between a first- and second-degree burn – and this information is explained a bit more, below – passes directly through the distant suburban town in which I was born, Highland Park.

[Image: Courtesy of CarlosLabs].

[Image: Courtesy of CarlosLabs].Waters along the shore of Lake Michigan would be instantly evaporated, forming radioactive rainstorms over northern Indiana, perhaps for days.

The size of the bomb can be varied, of course; here we see Los Angeles hit by any typical nuclear warhead carried by an American fighter jet, circa 1991; and, below that, we see New York City hit by a bomb equivalent to Fat Man, the device dropped on Nagasaki.

[Images: Courtesy of CarlosLabs].

[Images: Courtesy of CarlosLabs].And here, below, is Rome hit by Little Boy, the bomb dropped on Hiroshima – and the first nuclear device ever used as an act of war.

If it's any consolation to Catholics – or architectural historians – the extreme, northwestern fringes of the Vatican would escape immediate harm.

[Image: Courtesy of CarlosLabs].

[Image: Courtesy of CarlosLabs].Alternatively, let's drop Little Boy on Edinburgh.

[Image: Courtesy of CarlosLabs].

[Image: Courtesy of CarlosLabs].All of this is visually arresting – seeing vast bruises like bull's eyes consume whole cities – but what does it really mean? What is each colored circle supposed to represent?

In the following image of Mumbai being hit by a nuclear missile equivalent to those used by the Chinese military, we see concentric rings of 1st, 2nd, and 3rd degree burns expanding outward from the detonation – a geometry of necrosis, suffocation, and death. Blisters and cancer would affect tens of thousands of people for miles in every direction (depending on prevailing winds).

[Image: Courtesy of CarlosLabs].

[Image: Courtesy of CarlosLabs].For some unexpected astronomical context, though, CarlosLabs has added a bizarre final option: seeing how asteroid impacts might compare with inter-urban nuclear war.

Tokyo – where the following image is centered – is not merely erased; struck by an asteroid, it's been placed at the heart of a planetary event, complete with rings of sunburn-equivalent injury spreading out across whole continents.

[Image: Courtesy of CarlosLabs].

[Image: Courtesy of CarlosLabs].Returning to the realm of historical likelihood, the image that somehow clarifies this the most for me – if, for no other reason, because I live there – is the following glimpse of San Francisco. The entire peninsula has been blasted into absolute, smoking oblivion by an explosion equal to Tsar Bomba.

The fact that you would be more or less screwed as far south as Fremont – and well east of Oakland – seems sobering, indeed.

You could be sitting in the west-facing window of an Oakland high-rise, watching an atomic fireball explode over San Francisco – which quickly expands to melt the glass you're looking through.

[Image: Courtesy of CarlosLabs].

[Image: Courtesy of CarlosLabs].A few quick points, meanwhile:

1) This will mean very little, and have no effect, but I am 100% behind complete nuclear disarmament. The U.S. taking the lead in this seems like something well worth pursuing.

2) In this context, I have to say that the books of Richard Rhodes cannot be recommended highly enough. His The Making of the Atomic Bomb – which I have to confess to having read only partially – is required reading for anyone interested in what intensive, well-funded efforts of design can – in this case, unfortunately – produce. The bomb as an act of national infrastructure.

3) Michael Light's book 100 Suns, a photographic survey of nuclear weapon tests, is as horrifying as it is visually spectacular, especially for anyone with an interest in human history (and its explosive intersection with enriched geology).

4) Gary Snyder has a great poem that I still think of now and again, 17 years after first reading it, called "Bomb Test." Originally written, I believe, in Kyoto in 1986, the poem presents nuclear weapons as a kind of new terrestrial element, something geologically unprecedented both in and on the surface of the earth – highly processed samples of mineral chemistry (uranium, plutonium) put into military service by rival superpowers.

"The fish float belly-up, for real," Snyder writes. "Uranium in the whites / of their eyes.

- They've been swimming

Deep down where it's black when a

Silvery snow of something queer

glinted in

From cirrus clouds to the seamounts,

Through all the food chains,

Shrimp to tuna, the currents,

Riding the waves.

Even now, the globally nomadic residues of nuclear weapons tests form a ghostly stratigraphic marker that can be found literally around the world, an all but permanent part of the earth's sedimentary record.

So, in the images that illustrate this post, we see what effects this geological discovery – the explosive power of rare elements – could have on the built geography of our species.

Nuclear war thus poetically equates to hurling enriched fragments of the earth's surface at your rivals. Call it weaponized geology: minerals made altogether unearthly, if not post-terrestrial, through anthropological intervention.

5) Here is a random assortment of nuclear bomb photography. These were all Cold War-era tests – but, someday, perhaps soon, architects and architecture bloggers will be looking at similar images, images that have captured the obliteration of constructed environments from Mumbai or Karachi to New York, London, or Tehran. This will happen, I would say; it might well occur within our lifetimes, or at least within the next century; and any even partially accurate future assessment of global urbanism must still take nuclear weapons into account.

Nuclear weapons present us with a kind of demonic skeleton key, capable of catastrophically unlocking any city in the world, no matter how dense or well-fortified, in mere seconds.

Finally, here is what would happen if a nuclear bomb was dropped on a relatively non-urban environment: in this case, the town of Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

Finally, here is what would happen if a nuclear bomb was dropped on a relatively non-urban environment: in this case, the town of Chapel Hill, North Carolina. [Image: Courtesy of CarlosLabs].

[Image: Courtesy of CarlosLabs].But this could just as easily have been Ann Arbor, Santa Cruz, Austin, Shrewsbury, Castleton, Aberystwyth, Marburg – it could just as easily have been anywhere on earth.

The overwhelming obliterative power of nuclear weapons turns them into a kind of ubiquitous anti-landscape, something that no geography, built or natural, can successfully resist.

All of which is simply a long-winded way of saying that while we now tend to measure threats against our cities in terms of armed gangs or contextually minor moments of staged terrorist assault, it's still interesting to remember that, hovering over all of this, is something that could simply annihilate cities altogether.

If we're going to study cities, in other words, then we should also study that which is radically anti-city.

(Spotted via Alexis Madrigal and Wired Science).

Comments are moderated.

If it's not spam, it will appear here shortly!

Geoff, you may also be interested in the Epicentre documentary made by my friend Danny Bradbury. More info at http://www.epicentremovie.com/

br -d

(P.S. It was nice seeing you and an interesting evening at UCL.)

i might be wrong, but this maplet looks to be "inspired" by eric meyer's tool from back in 2005

mapping doomsday and the High-Yield Detonation Effects Simulator

I went to NC State and live in Mebane, and I was thinking your map of Chapel Hill actually looks like an improvement!

Just kidding, but joking aside this is serious and scary stuff.

My thinking on this is that it is impossible to assure that the world will disarm. Disarming us and our allies only assures that evil national powers can bomb whoever they want without fear of reprisal. As scary a thought as it is, the idea of "mutually assured destruction" has most likely been the greatest deterrent against international nuclear warfare. I think MAD is still necessary to keep countries like Iran and NK in check.

However, MAD is exactly why this new age of terrorism is so terrifying. MAD is not effective against rouge terrorists. Preventing nuclear proliferation is more important then ever.

And what is the key to halting nuclear proliferation? You have to fight proliferation at its source. National sponsors of terrorism who are working to develop nuclear weapons need to be shut down.

On a completely different note, pictures like the ones shown here show the scary face of nuclear energy. However, harnessed nuclear energy can be used for good. Nuclear fuel provides such a huge energy return, and the waste can be recycled and used to produce even more energy. They have been doing this in France for years.

With so much uncertainty surrounding fossil fuels, nuclear energy needs to be on the table in discussions about alternative energy sources. So much of the stigmata is unfounded and nuclear energy has the potential to be used for so much good.

Perhaps like many others, I began experimenting with the application by detonating a bomb over my home (I notice that Geoff did something similar). Why? Obviously it is about understanding the impact of the bomb through the experience of the familiar, but in my case it was a little more nuanced than that. The familiar in my case was synonymous with the walkable or had-walked: I perceived the damage done by the Little Boy by comparing it to my embodied understanding of those neighbourhoods I have walked so many times.

In her essay "The Indeterminate Mapping of the Common," Doina Petrescu notes the links between the nomadic subject and the beginning of architecture, which she locates in the work of Francesco Careri:

*****

In his book Walkscapes, Francesco Careri suggests that the 'architectural' construction of space began with human beings wandering in the Palaeolithic landscape: following traces, leaving traces. The slow appropriation of the territory was the result of this incessant walking of the first humans.

By considering 'walking' as the beginning of architecture, Careri proposes another history of architecture – one which is not that of settlements, cities and buildings made of stones but of movements, displacements and flows …. It is an architecture which speaks about space not as being contained by walls but as made of routes, paths and relationships. Careri suggests that there is something common in the system of representation that we find in the plan of the Palaeolithic village, the walkabouts of the Australian aborigines and the psychogeographic maps of the Situationists. If for the settler, the space between settlements is empty, for the nomad, the errant, the walker – this space is full of traces: they inhabit space through the points, lines, stains and impressions, through the material and symbolic marks left in the landscape. These traces could be understood as a first grasping of what is common, as a first tool to size and constitute resources for a constantly moving and changing community.

*****

In other words, returning to the above discussion of Ground Zero, while walking is another way of understanding the history of the city, it is perhaps also a way of understanding that which is "radically anti-city"?

It would be interesting if these visualisations represented the fallout plumes of each bombing. To me, that's the spookiest and most disturbing part of nuclear war - most people aren't going to see the bright, bright flash or feel the hurricane of hot wind but, as they say, we're all downwinders.

One (extremely simplistic) approach to this would be to tie in the mapping to climatic data - at the least show the effect on the direction that the prevailing wind would have, and maybe even use live data to show how the plume might fall if the bomb was dropped right now - at the moment that you click your mouse.

I notice that the blast zones are elliptical not circular, with the long axis E-W, Why is this?

Is it a polar magnetic thing or something to do with the revolution of the globe? Or is the simulation wrong?

Are there any rocket scientists out there who can answer me this

Anyone???

"Waters along the shore of Lake Michigan would be instantly evaporated, forming radioactive rainstorms over northern Indiana"

And how is this any worse than Gary? I kid!

Was hoping you'd mention "100 Suns" -- it's extraordinary, perhaps my favorite "art" book of all time.

Also pleased to see the Harold Edgerton high-speed pics of the bombs' nebulous... nearly Satantic?... first instants -- somehow even more menacing than the more familiar (almost cozy and comforting!) mushroom clouds.

Anonymous, I think it is a result from distortion in mapping, that is when you produce a flat image from a curved solid object thing get a bit warped!

Saw the anime BAREFOOT GEN once; it's based on a manga drawn by a Hiroshima survivor and shows what it was like. If I'd had any enthusiasm for nuclear weapons, that would have killed it:(

Does the tool take terrain into account, or just assume a perfectly flat surface? Even small hills can make a big difference to radiant heat effects (I seem to recall that Nagasaki is a lot hillier than Hiroshima, and hence suffered slightly less from the atomic bombing in World War II).

Geoff,

If you've not read Cormac McCarthy's The Road, I'd like to recommend it to you... and to anyone else. Not that we're as likely nowadays to see such a global exchange, but we're not totally out of the range of such a possibility, either. Can you imagine taking the time to paint over large sections of the globe with overlapping circles?

I grew up in the era of fear over global nuclear war. It still scares me. Only now it's "dirty bombs" and suitcase nukes we have to worry about more.

As for those who never see the flash or hear the thunder of death, but who suffer from the fallout from the exchange, you can't pick a better movie of their fate than Testament.

These maps are excellent in showing the power of a nuclear bomb in relation to a city, and so they give scale to something that would normally be a bit beyond ordinary comprehension.

However, recall that most cities have a mixture of hard and soft targets, and high value and low value targets. Couple this reality of target complexity with MIRV (multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles) technology, and it is obvious and widely known that most cities would in fact be targeted by many more than one bomb, and you realize that these overlays dramatically underestimate the likely damage that would actually occur in any given city...

Aerial views of the Bombardment of New York City, Circa 1948 (and its aftermath) — paintings by Chesley Bonestell. There's a detailed description of Bonestell's Moon-launched nuclear Armageddon in Philip Handleman's 2003 book Combat in the Sky: The Art of Aerial Warfare.

And to bring reality down to a more personal level, see the art of atomic bomb survivors from Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

According to the current Doomsday Clock Overview at the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, it ain't over yet:

"For most of the Cold War, overt hostility between the United States and Soviet Union, coupled with their enormous nuclear arsenals, defined the nuclear threat. The U.S. arsenal peaked at about 30,000 warheads in the mid-1960s and the Soviet arsenal at 40,000 warheads in the 1980s, dwarfing all other nuclear weapon states. The scenario for nuclear holocaust was simple: Heightened tensions between the two jittery superpowers would lead to an all-out nuclear exchange. Today, the potential for an accidental or inadvertent nuclear exchange between the United States and Russia remains, with both countries anachronistically maintaining more than 1,000 warheads on high alert, ready to launch within tens of minutes, even though a deliberate attack by Russia or the United States on the other seems improbable.

Unfortunately, however, in a globalized world with porous national borders, rapid communications, and expanded commerce in dual-use technologies, nuclear know-how and materials travel more widely and easily than before--raising the possibility that terrorists could obtain such materials and crudely construct a nuclear device of their own. The materials necessary to construct a bomb pervade the world--in part due to programs initiated by the United States and Soviet Union to spread civilian nuclear power technology and research reactors during the Cold War."

Improbability remains problematic.

Lucky for you, no-one's ever built a version of the Tsar Bomba small enough to put in a plane or launch on a missile. Not that I'd like to be hit by anything of any size, mind.

I was in elementary and junior high school in the early-to-mid 80s and had a morbid fascination with nuclear war, mostly due to events of that time and consumption of all the books and movies on the theme I could find (and there were lots). I re-watched the British telemovie Threads again recently; it was just as chilling 20 years on.

Eliminating nukes completely is a bit like trying to put toothpaste back in the tube, though. What has been learned cannot be un-learned, and for every hundred people who'd like to see nuclear weapons gone, there is at least one person who'd like to set one off.

In any population, 10% of people are good, 10% of people are bad, and the rest are like sheep waiting to follow. If the 10% that are bad occupy 55% of the positions of power then we're all stuffed.

For a bad night's sleep re global nuclear war, read Cormac McCarthy's THE ROAD.

another recommendation from the realm of atomic-bomb literature:

Riddley Walker by Russell Hoban

(I didn't include a link, because anything you could read about this book would be a spoiler: the story divulges its setting and context very slowly and at its own careful pace... just go get it at the library!)

Isn't it strange though how these images from nuclear tests produce a kind of eerie beauty? Especially the images from the hydrogen tests are very much liable to produce this effect in people.

I myself had image #4 hanging on my bedroom wall in full color for years...the motivation behind that I no longer fully understand.

The last map gave me goosebumps - I live in Carrboro, and work in Chapel Hill.

for the last 20 years people have been forced off the land and encouraged to move to population centers, now its cutesy talk to play nuke ball.

Its not cute, not appreciated and makes our "civilized" society look like a waste of time.

Id take a witch doctor over a mad scientist any day of the week.

Meanwhile the news media tries to frighten us about Iran, knowing full well that we don't invade a country unless we're sure they cant defend themselves.

this dialectic bs is getting old

Since you correctly put atomic bombs in context of comparing them to a meteor hit, try putting them in the perspective of time.

The two bombs dropped by the US in war were made in 1945. Now imagine how much technology has advanced since then. E.G. We now have color pictures!! In just 8 short years, they "advanced" from 70 kilotons to 50 megatons. The military has been constantly "improving" them since, and they're not telling how big they can make them now.

These maps do an unfortunate service in that they seem to indicate that humans would survive a nuclear war. Things won't happen in the way they are designed.

--Look up "EMP" or Electro-Magnetic Pulse effect. It is even in Wikipedia. It was discovered in a 1950's test over Bikini Island that knocked out Street lights in Hawaii, finally ending above ground nuclear testing. Focusing the EMP effect of a high altitude nuke is the way a nuclear war might be fought. Why inherit a nuclear wasteland when you can blow out a continent's electricity grid and wait for the people to kill themselves scrambling for whatever they can scratch up to live on?

Since humans have been making war for their 6000 years of written society, if there are no serious effort to rid ourselves of these terrible things, there is only one possible destination for mankind.

Regarding the asteroid - I'm not sure why they even put that on there. The damage of an asteroid impact would be *highly* variable, so drawing a damage circle is rather odd (it could be 10x larger, or a million times smaller).

In just 8 short years, they "advanced" from 70 kilotons to 50 megatons. The military has been constantly "improving" them since, and they're not telling how big they can make them now.

The military hasn't produced more powerful nuclear weapons. There's a point at which 'making them more powerful' is pointless. Keep in mind that bombs explode in 3-dimensions, but everything you want to destroy lies on a 2-d plane. This means doubling the "power" of a bomb doesn't double its damage. After a certain point, it gets pointless to make larger bombs. Rather, the military has invested in making smaller, lighter bombs that use less nuclear material with the same explosive power. This allows them to be loaded on (say) cruise missiles. They also created MIRVs decades ago. (MIRVs are multiple bombs loaded into a single missile. These individual bombs form a cluster of bombs which all explode within one area - this is far more efficient way to damage a large area than making a 'bigger bomb'.)

yeah Highland Park!

perfect timing for me as I am full of hot raging Beijing hate currently, I am forced to be here. Maybe this will calm my nerves down a bit.

I can't remember exactly who came up with this first, but I will quote "the greatest threat to the survival of humanity is climate change - to deal with this we need an operation on (at least) the scale of the Manhatton Project" c'mon Obama - expand Nevada Solar One!

May the crew of the Enola Gay rot in hell.

Post a Comment