The Lost Airfields of Greater Los Angeles

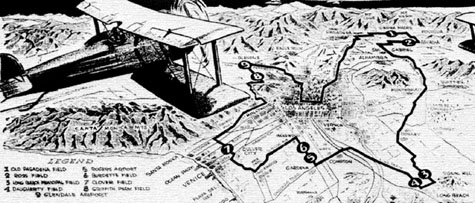

[Image: An airplane flies above Los Angeles, a landscape of now-forgotten airports].

[Image: An airplane flies above Los Angeles, a landscape of now-forgotten airports].Buried beneath the streets of Los Angeles are lost airfields, airports whose runways have long since disappeared, sealed beneath roads and residential housing blocks, landscaped into non-existence and forgotten. Under the building you're now sitting in, somewhere in greater L.A., airplanes might once have taken flight.

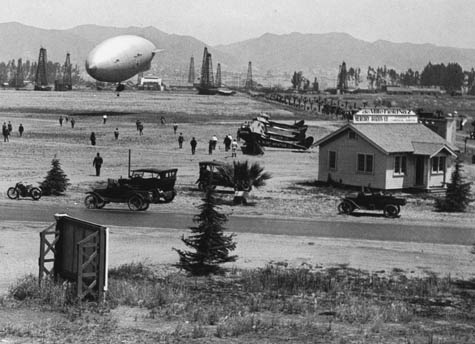

[Image: The now-lost runways of L.A.'s Cecil B. De Mille Airfield; photo courtesy of UCLA's Re-Mapping Hollywood archive].

[Image: The now-lost runways of L.A.'s Cecil B. De Mille Airfield; photo courtesy of UCLA's Re-Mapping Hollywood archive].The Cecil B. De Mille Airfield, for instance, described by the Re-Mapping Hollywood archive at UCLA as having once stood "on the northwest corner of Wilshire Boulevard and Crescent Avenue (now Fairfax)," would, today, be opposite The Grove; on the southwest corner of the same intersection was Charlie Chaplin Airfield. As their names would indicate, these private (and, by modern standards, extremely small) airports were used by movie studios both for transportation and filming sky scenes. They were aerial back-lots.

Other examples include Burdett Airport, located at the intersection of 94th Street and Western Avenue in what is now Inglewood; the fascinating history of Hughes Airport in Culver City; the evocatively named, and now erased, Puente Hills "Skyranch"; and at least a dozen others, all documented by Paul Freeman's aero-archaeology site, Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields (four pages alone are dedicated to lost L.A. airfields).

[Image: Charlie Chaplin Airfield in 1920s Los Angeles; photo courtesy of UCLA's Re-Mapping Hollywood archive].

[Image: Charlie Chaplin Airfield in 1920s Los Angeles; photo courtesy of UCLA's Re-Mapping Hollywood archive].In a way, though, these airports are like the Nazca Lines of Los Angeles – or perhaps they are even more like Ley lines beneath the city. Laminated beneath 20th century city growth, their forgotten geometries once diagrammed an anthropological experience of the sky, spatial evidence of human contact with the middle atmosphere. Perhaps we should build aerial cathedralry there, to mark these places where human beings once ascended. A winged Calvary.

The cast of minor characters who once crossed paths with those airfields is, itself, fascinating. A minor history of L.A. aviators would include men like Moye W. Stephens. Stephens's charismatic globe-trotting adventures, flying over Mt. Everest in the early 1930s, visiting Timbuktu by air, and buzzing above the Taj Mahal, would not be out of place in a novel by Roberto Bolaño or an unpublished memoir by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. And that's before we really discuss Howard Hughes.

[Image: The Cecil B. De Mille Airfield, renamed Rogers Airport (or, possibly, Rogers Airport, which later became the Cecil B. De Mille Airfield); image via Paul Freeman's Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields].

[Image: The Cecil B. De Mille Airfield, renamed Rogers Airport (or, possibly, Rogers Airport, which later became the Cecil B. De Mille Airfield); image via Paul Freeman's Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields].Of course, many of these aeroglyphs are now gone, but perhaps their remnants are still detectable – in obscure property law documents at City Hall, otherwise inexplicable detours taken by underground utility cables, or even in jurisdictional disputes at the L.A. fire department.

And they could even yet be excavated.

A new archaeology of airfields could be inaugurated at the corner of Wilshire and Fairfax, where a group of students from UCLA will brush aside modern concrete and gravel to find fading marks of airplanes that touched down 90 years ago, over-loaded with film equipment, in what was then a rural desert.

With trowels and Leica site-scanning equipment in hand, they look for the earthbound traces of aerial events, a kingdom of the sky that once existed here, anchored down at these and other points throughout the L.A. basin, cutting down into the earth to deduce what once might have happened high above.

Comments are moderated.

If it's not spam, it will appear here shortly!

Great post. DeMille's airfield is now the site of a 99 Cents Store and Johnie's restaurant, a classic bit of Googie architecture in LA. It's right across the street from LACMA (where I work). We recently did a post of our own that reached back to this era...

Also - when we were preparing to build Renzo Piano's Broad Contemporary Art Museum on our campus, it wasn't evidence of airfields that we dug up - it was prehistoric bones!

Nice - Scott, just linked your post in my "Quick Links" section. Thanks for pointing it out!

I enjoy this as well, as someone that lives on Skyview Rd., right off Airport Blvd. in Austin. Neither of which have airports on them any longer. Airport did until just about 10 years ago, but the airport that Skyview was connected to was gone before '50. But the hangar is still just a few blocks away, soon (hopefully, it's a graffiti magnet) to be demolished.

You can still find airport remnants in the street names. Airdrome St. just S. of Pico Blvd. Cloverfield, a contraction of Clover Field which is the original name of Santa Monica Airport. Avenida Aeropuerto in San Juan Capistrano borders the former site of Capistrano Airport.

While reading your post, the thought that was constantly fluttering through my mind was how the major developers of Los Angeles were not able to pick up on the fact that even in the 1920’s, people were challenging the spatial dimensions of L.A.’s sprawling landscape. Even with minimal technology and ultimately no urban achievement, the fact that a relevant form of transportation was aviation is astounding. Granted, Los Angeles in the 1920’s mostly consisted of farming land and had very few major roads. However, the fact that airstrips were owned by private individuals and were commonly used in areas where shopping malls now reside speaks wonders for where we went wrong. What possessed us to expand so foolishly? And possibly even more importantly, how was it achievable for there for to be a plethora of airstrips in activity at one given moment in Los Angeles in the 1920’s? I doubt there were air traffic controllers regulating Howard Hughes’ hourly take offs and arrivals making sure he never collided with Charlie Chaplin. The existence and achievements of the airstrips brings light to a time in Los Angeles’ history when anything was possible, when the sky was in fact not the limit, and when daily life was not limited by urban planners’ inefficiencies but rather dictated by practicality. But when practical means of transportation revolve around getting airborne to travel ten to fifteen miles, the urban fabric of a city must begin to be questioned in order to preserve the ingenuity and very uniqueness of the city itself. What William Mulholland was able to imagine and implement for the city of L.A. is comparable to what needed to be done with the other facets of the city. His roads were able to deliver water from hundreds of miles away to all of corners of L.A., why couldn’t anyone else manage to figure out how to get people from Downtown to Santa Monica in under an hour?

The abandoned airfield site is a total goldmine. I plan on spending hours trolling through that site. My favorite part is that many of the airfields have photos showing their evolution (and ultimate destruction), it's just an amazing walk through time. Many opened in the early 20th century and the shots have this real Gatsby feel to them and then by the late twentieth century and early 21st, most have been turned into condos or strip malls. It made me long for another time.

There were at least two airfields in Glendale - the Grand Central (Grand Central Ave is the old runway, and the Art Deco terminalstill standing, and now surrounded by Disney Imagineering offices) and Lesile Brand's personal runaway (now El Miradero Street just below the Brand Library). The City has some documentation of this on their website > http://www.ci.glendale.ca.us/GCATG/home.html

Back in the 20s the Hollywood types and other LA tycoons were not flying 10 and 15 miles in airplanes for transportation. They had handmade Bugati roadsters and Duesenbergs for that. They did fly up and down California routinely however. Whether for a film shoot or to check on a project or to get out of town for the weekend. There wasn't much practical about these airports except for the very wealthy. Personal air travel was mostly a form of conspicuous consumption. Hearst ran private trains up to San Simeon too, but this does not mean he was an early advocate of high-speed rail. It means he was a seriously rich dude. There are still private airports and some rich folks still own planes. But not at Fairfax and Wilshire, granted.

There was an airport near my college that was closed in the 80s. After it was gone the only real visible reminder was the fact that the overhead electrical lines alongside the highway changed to burried for a a hundred yards near the end of the old runway.

Post a Comment