Manhattan Paleolimnology

Temporary lakes have sprung up all over Manhattan again this week, sometimes more than twenty feet wide and a foot deep, spanning curbs and pooling in gutters, the aquatic remains of last week's rain and snowmelt.

[Image: Photo by Flickr-user ShellyS].

[Image: Photo by Flickr-user ShellyS].

This surprise limnology—often demanding new, indirect lines of approach from one side of the street to the next—reminded me of David Gissen's recent, recommended book Subnature, which includes an entire chapter on urban puddles.

"Although we often think of puddles as inconsequential," Gissen writes, "they appear in architectural history in prominent ways—in drawings of ruins, photographs of decaying buildings, and experimental designs that attempt to use water in provocative ways." Now, however, "these stagnant pools of water, once signifying society's vulnerabilities, appear to have disappeared in much contemporary work"; indeed, he adds, contemporary architects have seemingly always "viewed stagnant water with suspicion." There is good medical reason for this suspicion, of course; indeed, the Centers for Disease Control advised last year that "neglected swimming pools"—i.e. stagnant bodies of water—are fast becoming vectors for mosquito-borne disease.

The CDC specifically cites "the adjustable rate mortgage and associated housing crises" as unexpected disease incubators: "Associated with home abandonment was the expanding number of neglected swimming pools, jacuzzis (hot tubs), and ornamental ponds. As chemicals deteriorated, invasive algal blooms created green swimming pools that were exploited rapidly by urban mosquitoes, thereby establishing a myriad of larval habitats within suburban neighborhoods," they wrote.

In any case, Gissen describes "visions of the undrainable city" as a kind of sickly counterpart to the modern, infrastructurally managed, rational metropolis, pointing out that "the waters inundating the modern city rained from above and surged from below." These overload our modern streets and sewers, bringing even 21st-century cities closer to the flooded Roman basements of Piranesi than to the hygienic visions of Le Corbusier, Gissen suggests. I'm reminded here of a disconcerting remark made by Alan Weisman in The World Without Us that the subways of New York City would be irreparably flooded within only 36 hours if the city's underground pumps ceased to function.

While reading Gissen's chapter on puddles, however, one of the first things that came to mind is that someone should produce a puddle map of New York—an urban atlas of temporary flooding. Set your parameters—puddles one foot deep by thirty-feet wide, say, or, more accurately, a volumetric guideline (at least one hundred square-feet of water or no less than 120 gallons)—and bring these fleeting aqueous forms into the geographic consciousness of the city.

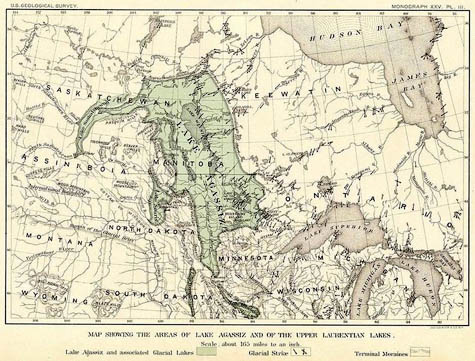

[Image: A map of glacial Lake Agassiz].

[Image: A map of glacial Lake Agassiz].

From one rainy season to the next, an accelerated paleolimnology of New York thus comes into being; the Lake Lahontans and Lake Agassizs of the five boroughs are given their cartographic due. Here a tiny lake once stood, historical plaques could read, bringing to mind a liquid version of Taylor Square, the famed "smallest park" in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

What monstrous puddles have existed in your neighborhood, and how have the urban circumstances of their existence changed over time? Did curb-cuts or new drains eliminate these hydro-geographies—or even make them worse? And whose lives have been affected by these unmapped bodies of water, whether through hydroplaning, sidewalk splashes, or even an expensive pair of ruined shoes?

Whole personal histories of human contact with puddles, and the effects such exposure might have, could be produced or recorded. This is extraordinary: we live beside temporary lakes and inland seas in cities all over the planet, yet these landmarks never make it onto our maps.

[Image: Photo by Flickr-user ShellyS].

[Image: Photo by Flickr-user ShellyS].This surprise limnology—often demanding new, indirect lines of approach from one side of the street to the next—reminded me of David Gissen's recent, recommended book Subnature, which includes an entire chapter on urban puddles.

"Although we often think of puddles as inconsequential," Gissen writes, "they appear in architectural history in prominent ways—in drawings of ruins, photographs of decaying buildings, and experimental designs that attempt to use water in provocative ways." Now, however, "these stagnant pools of water, once signifying society's vulnerabilities, appear to have disappeared in much contemporary work"; indeed, he adds, contemporary architects have seemingly always "viewed stagnant water with suspicion." There is good medical reason for this suspicion, of course; indeed, the Centers for Disease Control advised last year that "neglected swimming pools"—i.e. stagnant bodies of water—are fast becoming vectors for mosquito-borne disease.

The CDC specifically cites "the adjustable rate mortgage and associated housing crises" as unexpected disease incubators: "Associated with home abandonment was the expanding number of neglected swimming pools, jacuzzis (hot tubs), and ornamental ponds. As chemicals deteriorated, invasive algal blooms created green swimming pools that were exploited rapidly by urban mosquitoes, thereby establishing a myriad of larval habitats within suburban neighborhoods," they wrote.

In any case, Gissen describes "visions of the undrainable city" as a kind of sickly counterpart to the modern, infrastructurally managed, rational metropolis, pointing out that "the waters inundating the modern city rained from above and surged from below." These overload our modern streets and sewers, bringing even 21st-century cities closer to the flooded Roman basements of Piranesi than to the hygienic visions of Le Corbusier, Gissen suggests. I'm reminded here of a disconcerting remark made by Alan Weisman in The World Without Us that the subways of New York City would be irreparably flooded within only 36 hours if the city's underground pumps ceased to function.

While reading Gissen's chapter on puddles, however, one of the first things that came to mind is that someone should produce a puddle map of New York—an urban atlas of temporary flooding. Set your parameters—puddles one foot deep by thirty-feet wide, say, or, more accurately, a volumetric guideline (at least one hundred square-feet of water or no less than 120 gallons)—and bring these fleeting aqueous forms into the geographic consciousness of the city.

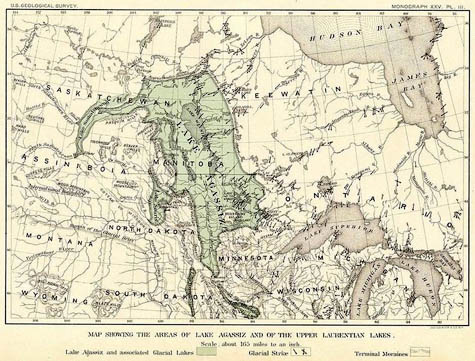

[Image: A map of glacial Lake Agassiz].

[Image: A map of glacial Lake Agassiz].From one rainy season to the next, an accelerated paleolimnology of New York thus comes into being; the Lake Lahontans and Lake Agassizs of the five boroughs are given their cartographic due. Here a tiny lake once stood, historical plaques could read, bringing to mind a liquid version of Taylor Square, the famed "smallest park" in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

What monstrous puddles have existed in your neighborhood, and how have the urban circumstances of their existence changed over time? Did curb-cuts or new drains eliminate these hydro-geographies—or even make them worse? And whose lives have been affected by these unmapped bodies of water, whether through hydroplaning, sidewalk splashes, or even an expensive pair of ruined shoes?

Whole personal histories of human contact with puddles, and the effects such exposure might have, could be produced or recorded. This is extraordinary: we live beside temporary lakes and inland seas in cities all over the planet, yet these landmarks never make it onto our maps.

Comments are moderated.

If it's not spam, it will appear here shortly!

Have a look at one of my favourite urban photographers, Rut Blees Luxemburg and her work for London Underground - puddles feature!

You might also enjoy Lewis Thomas' essay "Ponds" in Medusa and the Snail: More Notes of a Biology Watcher. Very cool picture of NY City construction site ponds in the 70s.

There's a great comic about mapping the puddles of New York in Ben Katchor's amazing collection, The Beauty Supply District. Sadly, I can't find a link to the actual strip, but seek it out--the whole book is fantastic.

When I was young, behind my house was a large field maintained by a company whose building was on the other side of it. Even though it was their property we kids treated it as an extension of our backyard, perfect for playing frisbee or baseball or lying in and looking at clouds.

There were two features that were particularly interesting about that field. One was a big piece of quartz in the ground that we used as "base" for tag, home plate for baseball, and so on. It was about flush with the ground when I was 6 or so and slowly disappeared into the earth.

The second was a huge puddle, I suppose you'd call it, which formed during especially wet springs. It covered a vast area and was deep enough that I could wade in up to my chest when I was little. When it formed we would put on our swimsuits and go splash around in it, delighted to have our own beach. (We had no care for the dangers of stagnant water, and in any case it drained off after a few days.) We called it Lake Doogan after our dog who also loved to swim in it.

When another company moved into the building they apparently decided there was no point in mowing the field and it's now completely covered in brambles and wild plants. It's a good habitat for many animals and I'm sure the change is for the better, but I suppose if Lake Doogan forms now it's only a marsh.

I think the most fascinating maps in the world would be ones drawn by children, even now when playing outside unsupervised is more rare than when I was young. I'm sure their maps would include such temporary bodies as Lake Doogan.

Love the McKim Mead and White building in the puddle. A high mark in American architecture unlikely we will surpass. Sorry Koolhouse!

A map of puddle locations would be very useful as a pedestrian, but how many variable-watermark maps get made? In marshes where the water level rises and falls with precipitation or tides are there maps for both high and low? Are they mapped at all? How does the fixed architecture of the city simplify mapping variable water levels?

It made me think of the dozens of ephemeral puddles, streams, and torrents that appeared over the past couple months all over Los Angeles as water pipes mysteriously ruptured, creating temporary aqueous features in this desiccated landscape.

"How does the fixed architecture of the city simplify mapping variable water levels?"

How many people know what rivers flow underneath their cities? There are a number in my native Milan, mostly covered by roads and some well into the Twentieth century, but I think I'm not alone in ignoring where they flow and what kind of effect they have on life at ground level.

My father was a boy when they paved over one of these bridges, but when people asked him for directions in the neighbourhood half a century later he'd still tell them to, say, "turn right at the bridge", even though there was no longer any such thing.

Here in California, CalTrans has either a map or a list of places on the freeways which flood every time it rains heavily. When the first rain of the season is forecast, they put up "Flooded" signs on barricades where it's going to flood, and leave them up until April.

As a child growing up in Sweden we had a natural feature a few hundred yards from our apartment blocks, a huge "pit" lined with grass slopes and a small copse of trees at the lowest point. At winter this would be a perfect place for bobsleighing and us poorer kids would just use old vinyl sheets to ride on down to the bottom trying not to hit any trees. Come spring time this snow would melt and the pit would be full of water about two foot deep. We would steal huge styrofoam insulation sheets from nearby construction sites and ride as boats using old hockey sticks to navigate through the waters. Of course we would all end up falling in at some point during our styrofoam naval battles but it was great fun until the county filled the pit in and drained any excess water. In April though, it looked and felt (despite the icy cold) as a small mangrove swamp and we were indians navigating it looking out for pirates and enemy tribes among the trees and submerged bushes.

Growing up in Manhattan, I loved the rainbows that appeared in street puddles as a result of oil leaking from cars and taxis. Even more beautiful at night with neon reflections in them.

re: mapping city puddles

In this interactive map of Venice on the National Geographic site, you can move the orange bar on the right to show where flooding occurs during high tides:

http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2009/08/venice/venice-animation

Post a Comment