|

|

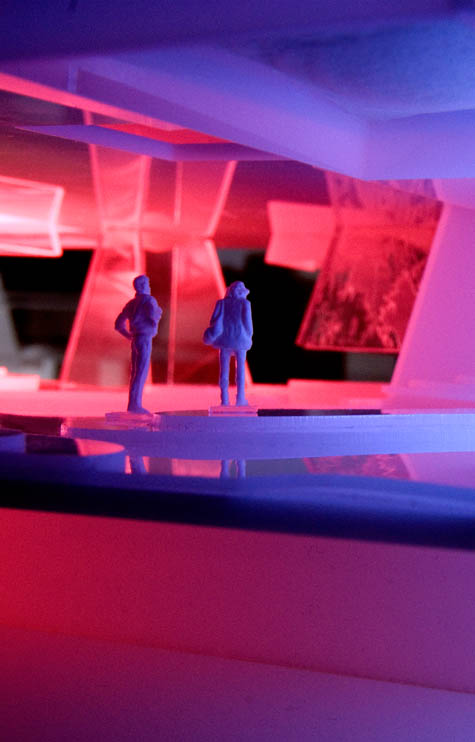

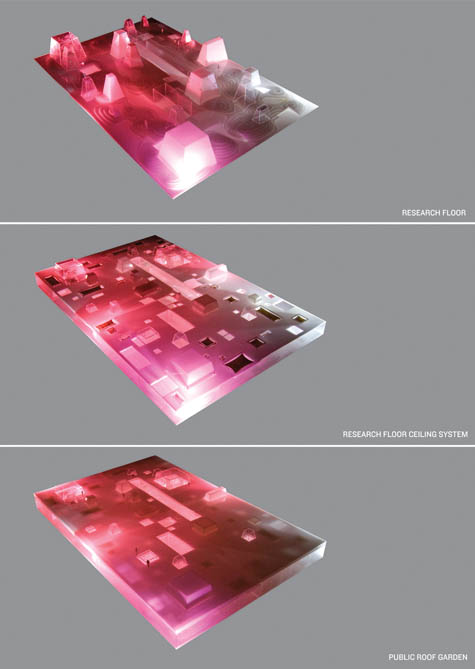

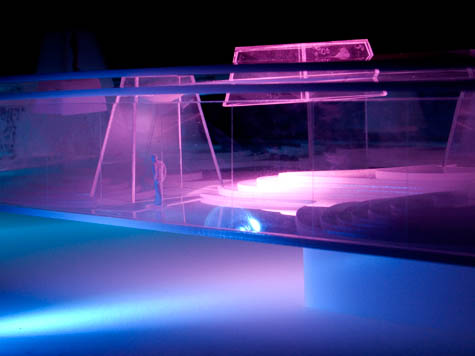

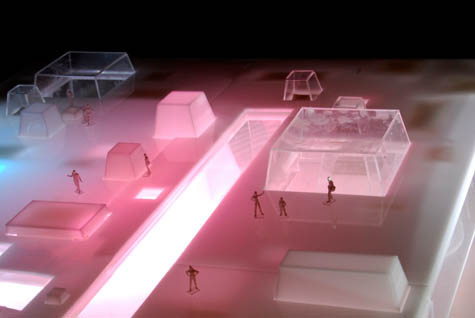

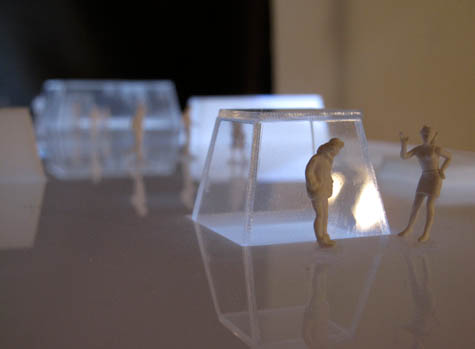

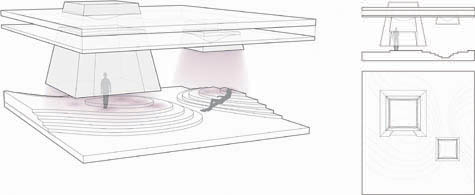

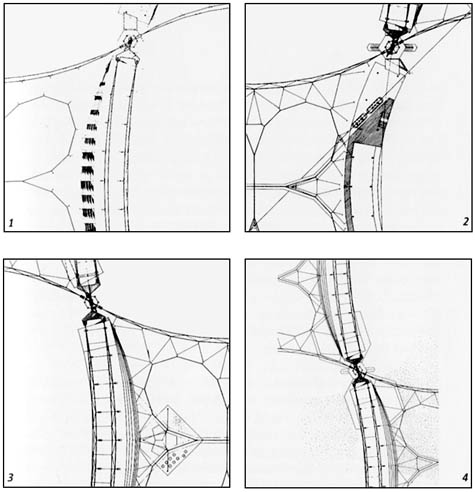

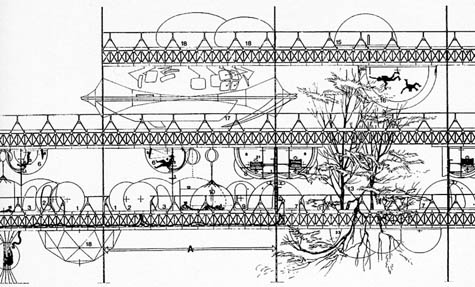

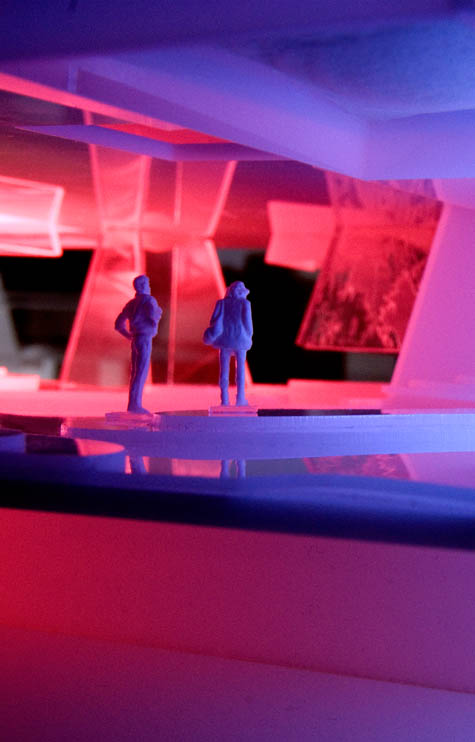

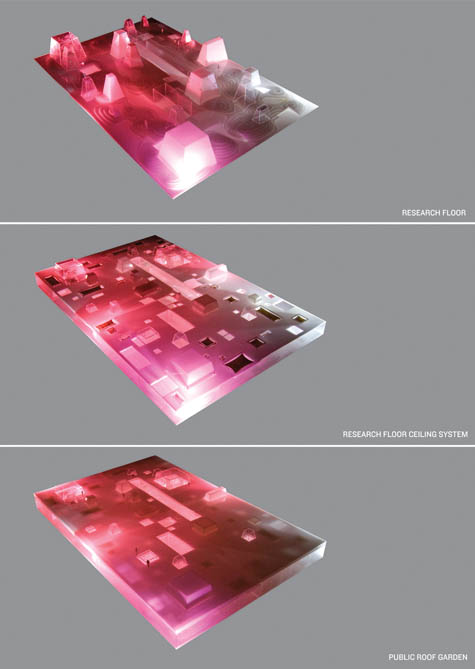

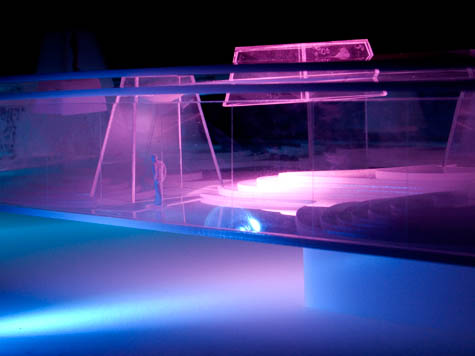

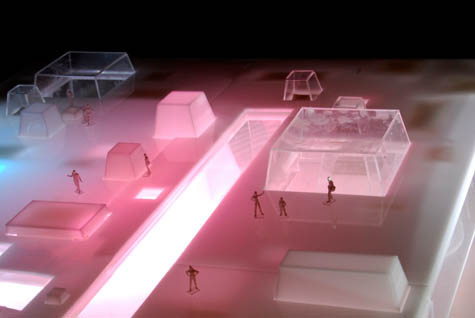

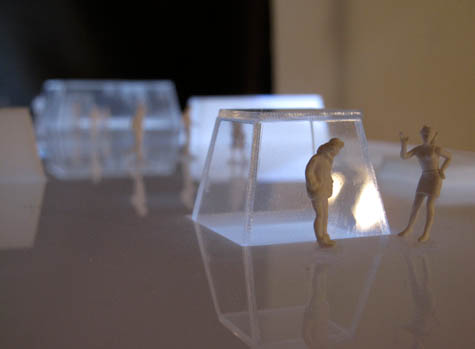

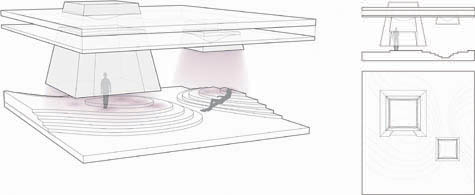

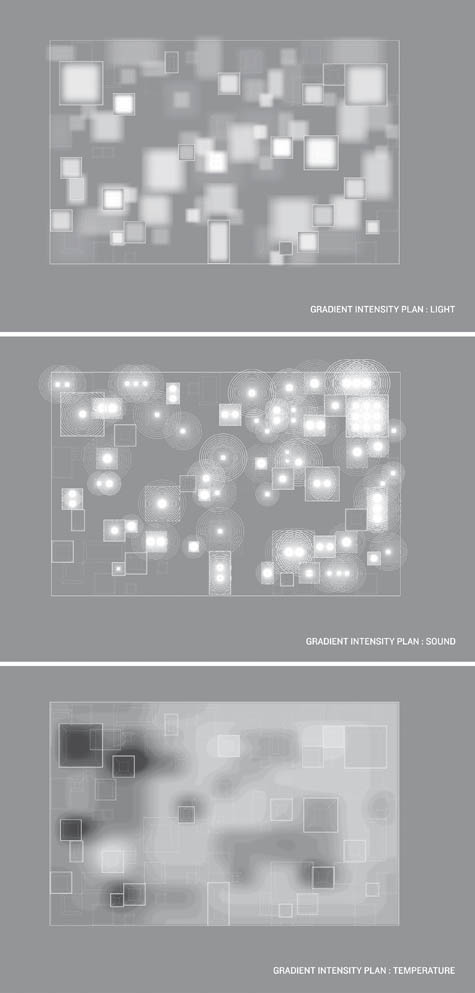

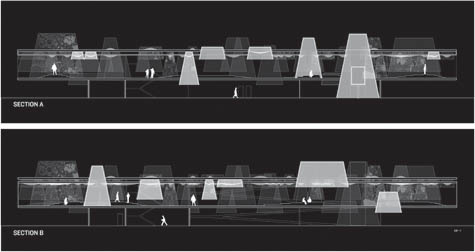

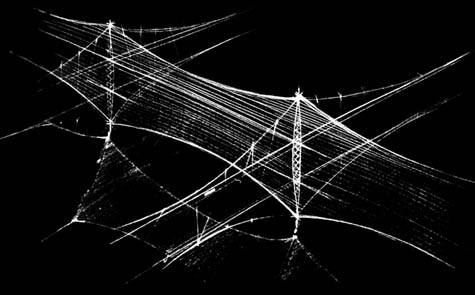

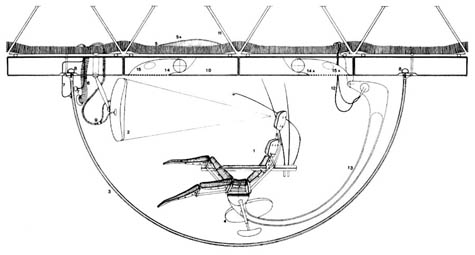

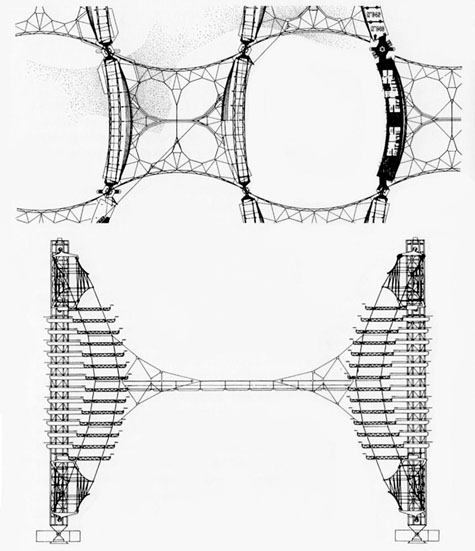

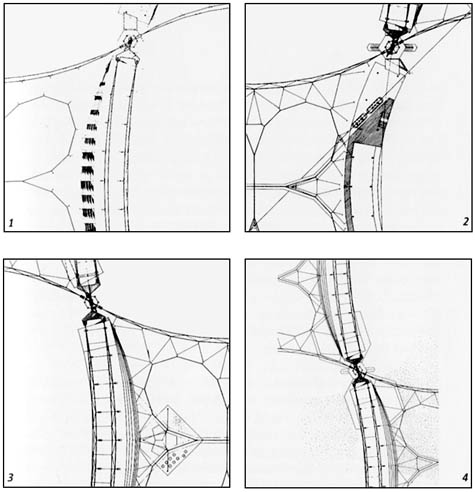

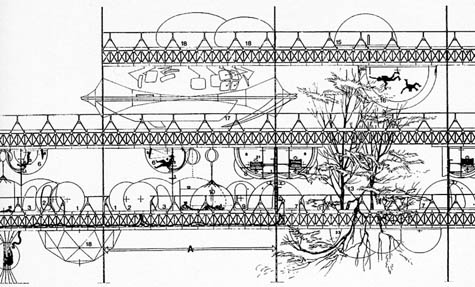

[Image: From "Change of Heart: Rethinking the Prescriptive Medical Environment" by Marina Nicollier]. [Image: From "Change of Heart: Rethinking the Prescriptive Medical Environment" by Marina Nicollier].The idea that architecture might have medical effects on the people who experience it was the premise of a project by Marina Nicollier produced this year at Rice University. In the project's accompanying documentation, Nicollier writes that we must learn "to create spaces that provide, through their experience and material substance, enough variability in environmental effects that individual differences in reception and response can be studied and used as a part of curative regimes." In other words, the sensorial experience of architecture could play a role in healing – or, as Nicollier explains, "spaces themselves should act as experiential platforms that provide a broader spectrum of environmental qualities, so that we may better understand their effects on our psychology – and ultimately, on our physiology."  [Image: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier]. [Image: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier].From the project description: The human body responds to its spatial and environmental surroundings in very subtle ways. Our most basic reactions to our environment can be read, essentially, in our vital signs; yet as many of these phenomena are subtle enough to be easily overlooked without some sort of monitoring device, they have been too often dismissed as fleeting emotional and sensorial effects that have little impact on our physiological system as a whole. These qualities can do much more. They can act as an architectural base for a very important body of research, expanding beyond the limited range of possibilities imposed on them by existing models of medical environments. To perform a test-run for these propositions, Nicollier has designed a "cardiology research facility adjacent to two major medical institutions in Mexico City." You would wander through the building, hooked up to electrocardiographs, every flutter of heart valve and sweat gland monitored by doctors from afar.  [Image: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier]. [Image: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier].I was on Nicollier's final thesis review the other week, where I joked that the project was like a visual combination of Barbarella and Constant's New Babylon, by way of A Clockwork Orange – an immensely positive combination, I might add. But that same impression strikes me today: that this is the kind of project Constant might have designed had he been more interested in the avant-garde spatial application of cardiac self-analysis. It is the megastructure as medical cocoon, architecture designed to stimulate the human nervous system.  [Image: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier; think of it as a Foucauldian application of Winston Churchill's famous phrase, that "We shape our buildings, and afterwards our buildings shape us." Only here, those buildings cause heart palpitations]. [Image: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier; think of it as a Foucauldian application of Winston Churchill's famous phrase, that "We shape our buildings, and afterwards our buildings shape us." Only here, those buildings cause heart palpitations].Nicollier's cardiology research lab "relies on an experience-based design generated on a series of gradient intensities," she writes. She then contrasts this brilliantly with the design of modernist sanitariums, highlighting what might be called the medical origin of modern architecture: Popular ideas about what constitutes a healthy environment gave rise to many of the components that became the formal trademarks of modernism – the flat roof was devised as a means to provide additional sunning surfaces for tubercular patients; while the deep verandas, wide private balconies, and covered corridors served as organizational tools to isolate contagious patients from the general staff. Indeed: Visits to these establishments were prescribed, as were the conditions and durations of the exposures themselves. Today, of course, there is ongoing research to determine how and to what extent environmental factors such as temperature, natural and artificial light, and sound affect our health, and despite there having been some interesting conclusions, it is still an area of research that requires more investigation and exploratory trials. Then, however, in the 1950s it was discovered that tuberculosis was only treatable through the use of antibiotics, and so architectural modernism – with its wide verandahs and flat roofs – lost its medical justification, so to speak. It became just another style to be mined for a new pastiche of superficial quirks and regional variations.   [Images: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier]. [Images: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier].Even the siting of the project, in Mexico City, plays on this development. Early modern sanitariums and "health resorts," Nicollier writes, were designed with "specific needs regarding their site." Their regime of exposure to light, temperature, and clean air limited called for very particular climatic conditions falling within acceptable ranges. This is why the vast majority of these facilities were built in remote, rather idyllic locations near the coast or tucked away in alpine forests, away from any urban centers, which were considered to be too dense and dirty to be of any use for a treatment regime. To wit, Thomas Mann's Magic Mountain. Locating a facility like this, then, in Mexico City, a notoriously polluted megalopolis, is to suggest that architecture can counteract – that is, influentially avoid negation by – even the most invasive and unnatural of contexts. The building "supplements the environmental qualities of the city, incorporating them into its intensity gradients," in Nicollier's words.   [Images: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier]. [Images: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier].But I find it almost overwhelmingly interesting to think that controlled exposure to a certain piece of architecture could actually be prescribed as a medical treatment. Viewed this way, the immersive experience of a well-designed space could actually stimulate one toward otherwise unknown medical highs and lows. A building becomes almost pharmaceutical – or narcotic – in its level of influence over those who use it. Could a building even become addictive?, one might ask. Could you experience something like withdrawal after going too long without experiencing it? Could you someday receive a prescription from a doctor telling you to visit a certain building for twenty minutes everyday, because the phenomenological impact of its vaulted galleries might cure you of whatever – kidney stones, anemia, or even manic-depression? Male pattern baldness. Sexual frigidity. Space is the treatment for the things that harm you.  [Image: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier]. [Image: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier].During the project review, we discussed whether it might be possible for the building to act as a template or prototype for other such projects elsewhere. That is, could you produce a kind of spatial franchise in which certain combinations of color, materiality, texture, sequence, and even scent would be put to use for medical purposes? The light, sound, and temperature of the building would thus act as a general format, available to other designers in utterly dissimilar circumstances. Perhaps it'd even be subject to regulation by the FDA and reproduced as a generic in Canada.  [Image: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier]. [Image: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier].The sections, meanwhile, are beautiful in their own way –   [Images: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier]. [Images: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier].– though I'm unashamedly a fan of the semi-psychedelic mood lighting of the actual models.  [Image: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier]. [Image: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier].To read a complete description of the project and see larger images, check out this Flickr set of the project. ("Change of Heart" was produced at Rice University under the supervision of Dawn Finley, Eva Franch Gilabert, Farès el-Dahdah, and Albert Pope).

Medical researchers have found that some of the streams, rivers, and groundwater in Patancheru, India, are really "a soup of 21 different active pharmaceutical ingredients, used in generics for treatment of hypertension, heart disease, chronic liver ailments, depression, gonorrhea, ulcers and other ailments. Half of the drugs measured at the highest levels of pharmaceuticals ever detected in the environment."

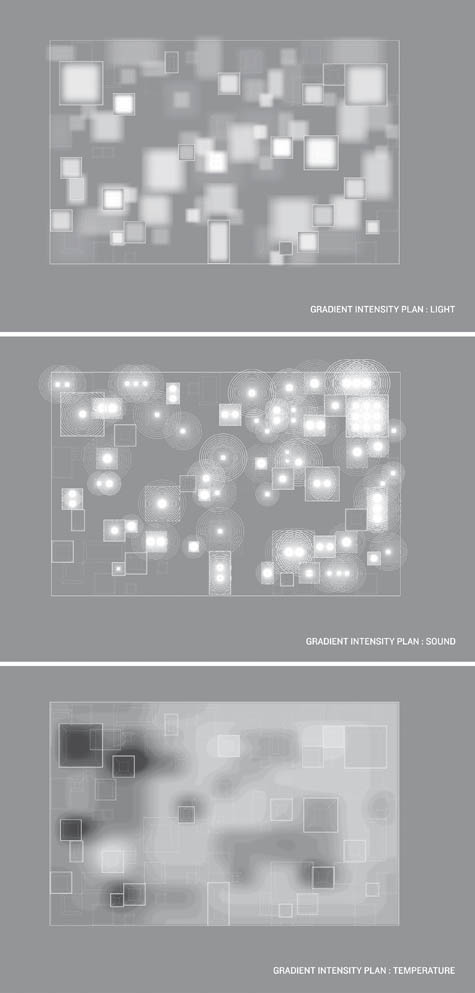

[Image: The Iska Vagu stream near Hyderabad, India. "Indian factories that make lifesaving drugs swallowed by millions worldwide are creating the worst pharmaceutical pollution ever measured," we read, "spewing enough of one antibiotic into a stream each day to treat everyone living in Sweden for a work week." Photo by AP Photo/Mahesh Kumar A]. [Image: The Iska Vagu stream near Hyderabad, India. "Indian factories that make lifesaving drugs swallowed by millions worldwide are creating the worst pharmaceutical pollution ever measured," we read, "spewing enough of one antibiotic into a stream each day to treat everyone living in Sweden for a work week." Photo by AP Photo/Mahesh Kumar A].

"If you just swallow a few gasps of water," a German doctor said to MSNBC, "you're treated for everything. The question is for how long?"

Indeed, all of this has the unsurprising effect that "some of India's poor are unwittingly consuming an array of chemicals that may be harmful, and could lead to the proliferation of drug-resistant bacteria." For instance, amongst this mix are high levels of Ciproflaxin: The more bacteria is exposed to a drug, the more likely that bacteria will mutate in a way that renders the drug ineffective. Such resistant bacteria can then possibly infect others who spread the bugs as they travel. Ciprofloxacin was once considered a powerful antibiotic of last resort, used to treat especially tenacious infections. But in recent years many bacteria have developed resistance to the drug, leaving it significantly less effective. With sources of freshwater all over the world now showing at least trace signs of pharmaceutical pollution, is some kind of global superbug brewing?

Aside from the very real health implications of this story, though, I'm fascinated by these drugs' effect on the landscape; in other words, millions of pounds' worth of loose pharmaceuticals will surely someday form a detectable layer in the soil, given time.

Pharmaco-geological formations take shape in the sand, compacted into strange new types of stone. The locals dissolve slices of it in their tea, as it's used to treat illnesses. Thousands of years pass; then millions. The rocks you're looking at in the wall of that canyon are made of lithified Prozac. Tylenol Gorge State Park.

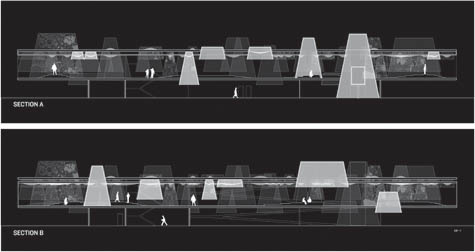

A deltaic geography of sedimentary Tamiflu is eventually mined as a building material; temples of this unusually smooth rock are built; visits to them are believed to help prevent infection.

And how will this affect plants? If river grasses and trees begin to accumulate this novel class of mineral, taking pharmaceutical-rich waters up into their roots, will it change the way they grow? Day of the Triffids.

"We don't have any other source, so we're drinking it," a local woman named R. Durgamma explains to MSNBC. In a chilling detail that reveals how those in power clearly know what is happening there, she adds: "When the local leaders come, we offer them water and they won't take it."

(Thanks, dad, for the link!)

I recently came across something I first read back in January 2004 about what might be called the private nationalization of Italy under Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi – when your country becomes a labyrinth of overlapping properties owned by one man – and it seemed interesting enough that I thought I'd re-post it here. So: Hi there,

I'm an Italian citizen living in Milan, in a building that was built by Immobiliare EdilNord, which is owned by the Prime Minister. I work part-time for the Pagine Utili, owned by the Prime Minister, but I might soon be contracted by Blockbuster, the famous chain owned by the Prime Minister. I've always been a fan of Milan, the soccer club of the Prime Minister. I go to work in a car which I first saw in an ad in Panorama, a weekly magazine owned by the Prime Minister, and which I bought secondhand from an employee of the Banca Mediolanum, a bank amongst whose biggest shareholders we find the Prime Minister. The insurance for the car is also owned by the Prime Minister, and when I'm driving I often listen to some radio stations... owned by the Prime Minister. When I leave my house I first accompany my neighbor, who works at the Finbanc Inversiones (owned by the Prime Minister) before I pick up some newspapers and magazines (also owned by the Prime Minister). Sometimes there's traffic on the way to work, and so to tell my colleagues I'll be late I use a cellphone of the Compagnia Telefonica Mobile, which sees the Prime Minister as one of its shareholders.

Some afternoons I go shopping in the supermarkets built by one of the Prime Minister's construction and development companies, where I buy products produced, published, and sponsored by the Prime Minister. In the evening I nearly always watch the television, nowadays completely in the hands of the Prime Minister, on which the movies (often produced by the Prime Minister) are continuously interrupted by commercials made by the Prime Minister's own publicity agency. Thus, through satellite, I try to get out of Italy to see if anything good is being transmitted elsewhere, but then it happens that I find TV networks functioning under Mediaset – which is owned by the Prime Minister. Distrustful and tired, I do some surfing on the internet via the Jumpy Provider, of NewMedia Investment, another property of the Prime Minister, and there I find lots of declarations of the Prime Minister, nearly all against his political opponents. Sundays I like to stay at home and just read books – which come from publishing companies owned by the Prime Minister.

Panta rei, everything proceeds – but for a while now I've heard a lot of whispering about the conflicts of interest in relation to our Prime Minister, so I ask myself: why? Is there something anomalous? This isn't how it's supposed to be?

My sincere greetings,

An Italian Citizen Originally published on Indymedia Italia.

In what sounds like the plot of a John Carpenter film, the Daily Telegraph reports that a village in Brazil might be populated by genetically altered twins created by notorious Nazi doctor Josef Mengele.  [Image: The Brazilian twin town of Josef Mengele]. [Image: The Brazilian twin town of Josef Mengele]."For years scientists have failed to discover why as many as one in five pregnancies in a small Brazilian town have resulted in twins – most of them blond haired and blue eyed," we read. "But residents of Candido Godoi now claim that Mengele made repeated visits there in the early 1960s, posing at first as a vet but then offering medical treatment to the women of the town." According to an historian named Jorge Camarasa who has written a book about Mengele's bio-genetic legacy, "Candido Godoi may have been Mengele's laboratory, where he finally managed to fulfil his dreams of creating a master race of blond haired, blue eyed Aryans. There is testimony that he attended women, followed their pregnancies, treated them with new types of drugs and preparations, that he talked of artificial insemination in human beings, and that he continued working with animals, proclaiming that he was capable of getting cows to produce male twins." The article points out that "the town's official crest shows two identical profiles and a road sign welcomes visitors to a 'Farming Community and Land of the Twins'. There is also a museum, the House of the Twins." "Nobody knows for sure exactly what date Mengele arrived in Candido Godoi," Camarasa adds, "but the first twins were born in 1963, the year in which we first hear reports of his presence." This sounds insanely implausible to me – more like a Nazi-infused origin story animated by a pronounced fear of witchcraft – but it's a fascinatingly bizarre proposition. In many ways, meanwhile, it reminds me quite strikingly of a book called The Angel Maker by Stefan Brijs, which I just picked up last week. The back cover description: The village of Wolfheim is a quiet little place until the geneticist Dr. Victor Hoppe returns after an absence of nearly twenty years. The doctor brings with him his infant children – three identical boys all sharing a disturbing disfigurement. He keeps them hidden away until Charlotte, the woman who is hired to care for them, begins to suspect that the triplets – and the good doctor – aren’t quite what they seem. As the villagers become increasingly suspicious, the story of Dr. Hoppe’s past begins to unfold, and the shocking secrets that he has been keeping are revealed. A chilling story that explores the ethical limits of science and religion, The Angel Maker is a haunting tale in the tradition of The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde and Frankenstein. Only here, it's Dr. Mengele creating dark angels in the rain forest. (Thanks, Steve!)

[Image: "Conceptual diagram of satellite triangulation," courtesy of the Office of NOAA Corps Operations (ONCO)]. [Image: "Conceptual diagram of satellite triangulation," courtesy of the Office of NOAA Corps Operations (ONCO)].

For several years I've been fascinated by what might be called the geological nature of harddrives – how certain mineral arrangements of metal and ferromagnetism result in our technological ability to store memories, save information, and leave previous versions of the present behind.

A harddrive would be a geological object as much as a technical one; it is a content-rich, heavily processed re-configuration of the earth's surface.

[Image: Geometry in the sky. "Diagram showing conceptual photographs of how satellite versus star background would appear from three different locations on the surface of the earth," courtesy of the Office of NOAA Corps Operations (ONCO)]. [Image: Geometry in the sky. "Diagram showing conceptual photographs of how satellite versus star background would appear from three different locations on the surface of the earth," courtesy of the Office of NOAA Corps Operations (ONCO)].

This reminds me of another ongoing fantasy of mine, which is that perhaps someday we won't actually need harddrives at all: we'll simply use geology itself.

In other words, what if we could manipulate the earth's own magnetic field and thus program data into the natural energy curtains of the planet? The earth would become a kind of spherical harddrive, with information stored in those moving webs of magnetic energy that both surround and penetrate its surface.

This extends yet further into an idea that perhaps whole planets out there, turning in space, are actually the harddrives of an intelligent species we otherwise have yet to encounter – like mnemonic Death Stars, they are spherical data-storage facilities made of content-rich bedrock – or, perhaps more interestingly, we might even yet discover, in some weird version of the future directed by James Cameron from a screenplay by Jules Verne, that the earth itself is already encoded with someone else's data, and that, down there in crustal formations of rock, crystalline archives shimmer.

I'm reminded of a line from William S. Burroughs's novel The Ticket That Exploded, in which we read that beneath all of this, hidden in the surface of the earth, is "a vast mineral consciousness near absolute zero thinking in slow formations of crystal."

[Image: "An IBM HDD head resting on a disk platter," courtesy of Wikipedia]. [Image: "An IBM HDD head resting on a disk platter," courtesy of Wikipedia].

In any case, this all came to mind again last night when I saw an article in New Scientist about how 3D holograms might revolutionize data storage. One hologram-encoded DVD, for instance, could hold an incredible 1000GB of information.

So how would these 3D holograms be formed?

"A pair of laser beams is used to write data into discs of light-sensitive plastic, with both aiming at the same spot," the article explains. "One beam shines continuously, while the other pulses on and off to encode patches that represent digital 0s and 1s."

The question, then, would be whether or not you could build a geotechnical version of this, some vast and slow-moving machine – manufactured by Komatsu – that moves over exposed faces of bedrock and "encodes" that geological formation with data. You would use it to inscribe information into the planet.

To use a cheap pun, you could store terrabytes of information.

But it'd be like some new form of plowing in which the furrows you produce are not for seeds but for data. An entirely new landscape design process results: a fragment of the earth formatted to store encrypted files. Data gardens. They can even be read by satellite.

[Image: The "worldwide satellite triangulation camera station network," courtesy of NOAA's Geodesy Collection]. [Image: The "worldwide satellite triangulation camera station network," courtesy of NOAA's Geodesy Collection].

Like something out of H.P. Lovecraft – or the most unhinged imaginations of early European explorers – future humans will look down uneasily at the earth they walk upon, knowing that vast holograms span that rocky darkness, spun like inexplicable cobwebs through the planet.

Beneath a massive stretch of rock in the remotest state-owned corner of Nevada, top secret government holograms await their future decryption. The planet thus becomes an archive.

(Earlier on BLDGBLOG: Geomagnetic Harddrive).

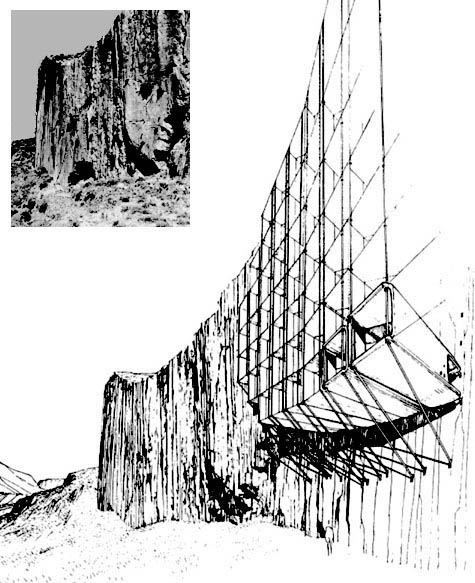

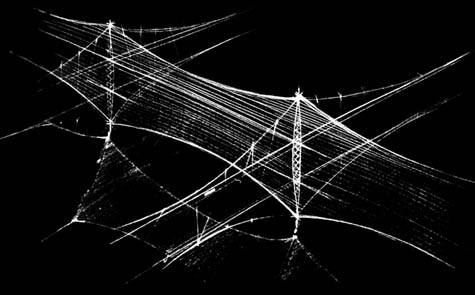

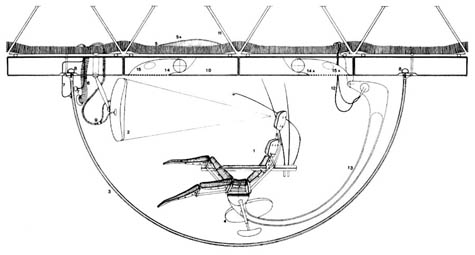

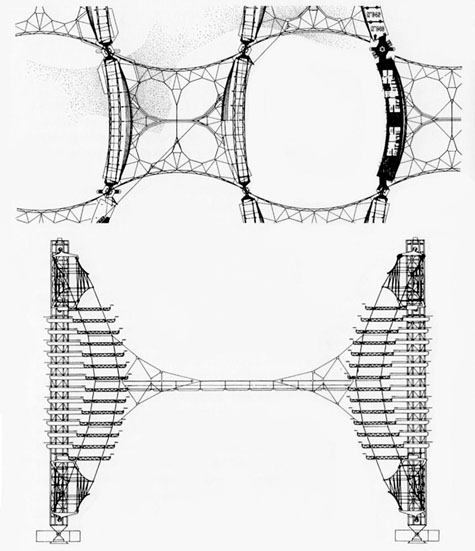

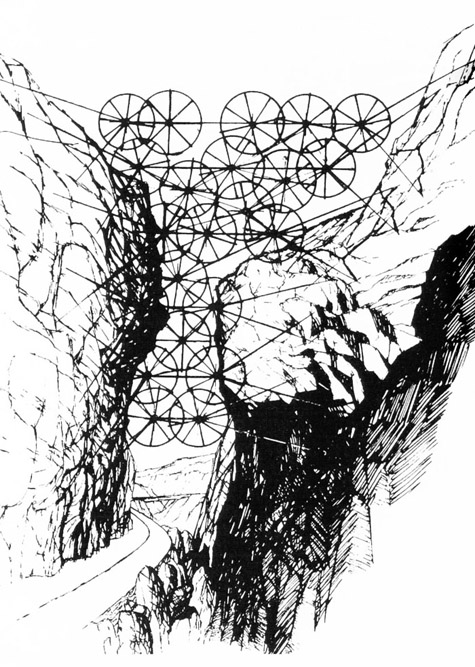

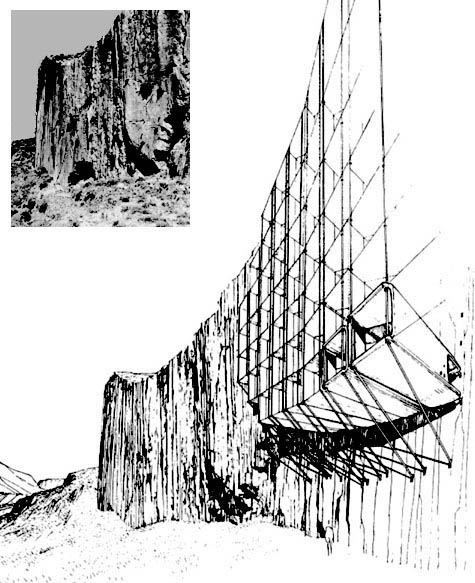

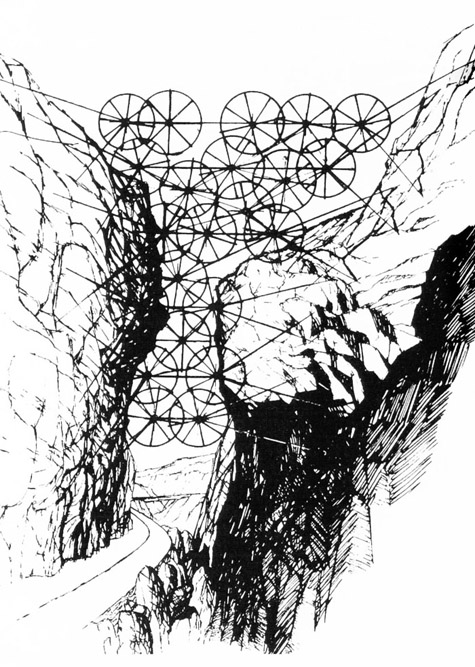

[Image: The Hanging Hotel by Takis Zenetos; think of it as the International Style meets the Potala Palace]. [Image: The Hanging Hotel by Takis Zenetos; think of it as the International Style meets the Potala Palace].Nearly a year ago, a reader named Stavros Koulis tipped me off to the work of Takis Zenetos. Zenetos was a Greek architect whose work seems clearly to belong in a list of avant-garde mid-to-late 20th century architects like Yona Friedman, Constant, and even Archigram, but who seems otherwise to have been overlooked. The above project – visible in the next image – is for a hanging hotel, a combination of Tibetan palace, Anasazi cliff dwelling, and artificial geological formation.  [Image: The Hanging Hotel, strung onto a cliffside like a musical instrument, by Takis Zenetos]. [Image: The Hanging Hotel, strung onto a cliffside like a musical instrument, by Takis Zenetos].But his most exciting project, I'd suggest (based on very little information, to be frank), is Cable City, an incredible 1961 design for a suspended city – what Zenetos called une ville suspendue. The entire metropolis would be hung from cables, a kind of tensional extension of the earth's surface.  [Image: The Cable City of Takis Zenetos]. [Image: The Cable City of Takis Zenetos]. To be honest, I've never read a word about this thing in English, so who knows what I'm getting right here; but the overall impetus behind the project seems to be something like counter-terrestriality: a city that would not only span, but even temporarily replace, the earth's surface, forming a cobweb of urban settlement. An extremely local architectural offworld made of capsules, wired Archigramian hammocks, and other high-tech micro-environments.  [Image: The Cable City of Takis Zenetos; the instant city as toupee]. [Image: The Cable City of Takis Zenetos; the instant city as toupee].But my own descriptions shouldn't get in the way of Zenetos's images.     [Images: The Cable City of Takis Zenetos]. [Images: The Cable City of Takis Zenetos].After all, he even drew gullies choked with wind turbines – sustainable, if bird-murdering, power stations – decades ahead of his time.  [Images: A turbined gorge by Takis Zenetos]. [Images: A turbined gorge by Takis Zenetos].I'd love to know more about Zenetos, if anyone reading BLDGBLOG has more information. "Takis Zenetos (1926-1978)," we read, "is the pre-eminent architect of Greek modernism, with a varied oeuvre (industrial buildings, schools, residences, objects, urban planning studies), and he is best known for the FIX building on Syngrou Avenue and the Lycabettus theatre. "What is not widely known is that Zenetos was a visionary of the future electronic city and the digital age." [Thanks to Stavros Koulis for sending me these scans].

[Image: From Manhattan's Annex by W. Amanda Chin. View larger]. [Image: From Manhattan's Annex by W. Amanda Chin. View larger].There are a few student projects from my trip the other week to Rice University that I'm going to be posting here over the next week or so – beginning with Manhattan's Annex: The Crosstown [of] Excess by W. Amanda Chin. For her thesis project at Rice, Chin proposed ten "waterscrapers" that would slice across the urban space of Manhattan, cutting through buildings, through parks, and through the urban grid itself, forming strange aquatic intersections with the city.  [Image: From Manhattan's Annex by W. Amanda Chin. Image slightly cropped: view larger]. [Image: From Manhattan's Annex by W. Amanda Chin. Image slightly cropped: view larger].Inside would be routes for scuba-diving, new aquariums, and multi-seasonal sites for public swimming. These above-ground pipes of water – like hydro-boulevards, or one might say the hydrological Haussmannization of Manhattan – are less an actual proposal for construction than a sort of architectural dream: the city cross-cut by amniotic utopias through which people can wander at all hours of the day.     [Images: From Manhattan's Annex by W. Amanda Chin; view larger]. [Images: From Manhattan's Annex by W. Amanda Chin; view larger].As you can see in the short comic strips that accompanied the project – see the larger Flickr set for more – the project is themed around overlapping idea of excess, self-indulgence, and addiction, as if these Voluntary Prisoners of Architecture-like scenes might be therapeutic, a mass psychotherapy of space. It's 3am and you're depressed; you can't sleep. You go out wandering across Harlem, inside one of the Annexes, completely alone, not a single other person in sight – when a group of people goes scuba-diving over your head. As if they've attained flight through an artificial river in the sky. In a city of insomniacs, the city itself becomes the dream. See more: Manhattan's Annex: The Crosstown [of] Excess by W. Amanda Chin.

[Image: From the series Cloud Projections by Blake Gordon]. [Image: From the series Cloud Projections by Blake Gordon].Photographer Blake Gordon has been documenting the geometric effects of light pollution in Austin, Texas, capturing thinly defined shapes in the clouds, projected upward from the tops of buildings. It's an accidental ornamentation of the city sky – or what Gordon calls Cloud Projections.  [Image: From the series Cloud Projections by Blake Gordon]. [Image: From the series Cloud Projections by Blake Gordon]."I captured defined patterns of light above the city when atmospheric conditions were right," he explained in an email. This is part of a larger interest in seeing "the clouds as a surface." For instance, Gordon mentioned that he had also produced "rough images from a plane flight in Minnesota where I saw the reverse: low winter clouds gave light pollution a medium to mark upon, and towns broadcast their cluster signals to those above." About these "broadcasts," Gordon asks: "Some of them were so precise that it's hard to conceive that they are just afterthoughts of a lighting design. Would it still be called light pollution?"  [Image: From the series Cloud Projections by Blake Gordon]. [Image: From the series Cloud Projections by Blake Gordon].While I'm instantly reminded of Paul Virilio's War and Cinema – where Virilio memorably describes the Nazi use of searchlights as a form of temporary light-architecture, creating a "space" of monumental vaults and upward-projected walls to help define their night rallies – I'm also struck by at least two possibilities here: 1) Airplanes could project downward onto the cloud canopy, showing anything from television shows to the latest Hollywood blockbuster to local weather and temperature information. The audience? The people in that particular aircraft. Like some strange technological implementation of Jacques Lacan, you'd be moving forward into a world defined by your own projections. Imagine, though, looking out across the city at other airplanes stuck in holding patterns, projecting films down onto the clouds of their respective flight paths. You glimpse scenes from The Dark Knight, Valkyrie, and The Wrestler. Or perhaps planes could project images in all directions, forming cylinders of imagery. An IMAX of the sky. Whenever you encounter clouds, your flight crew switches on the outside projectors... and everyone gazes out at that ghostly presence, a dream-cloud of film passing hundreds of miles per hour through the inner atmosphere. 2) Buildings could project films upward onto the cloud canopy. For your next corporate party you hire SkyTV: a patented, cinematic approach to urban cloud cover. Drive-in cinemas would no longer exist; high-rises would, instead, have installed bleachers on their roofs, like those old tiered seats you find atop houses near Wrigley Field, put there so you can see the game without an official ticket. Only, here, those bleachers are tilted back like planetarium seats – and everyone is watching the sky. a) Even without shining films into the sky, this would be an amazing idea: turning the whole city into a planetarium. Perhaps astronomers should be asking: Why aren't there sky-bleachers on every roof? You're out on a date some night and you're invited to stop by a friend's party – but everyone seems to be heading up onto the roof. You both follow, drinks in hand – and soon you're out on the roofscape, nervous amidst bleachers, gigantic hulking silhouettes against the night sky. And there are dozens and dozens of people up there, reclined in near-silence, watching the constellations. There are thousands of buildings around the city like this, you're told. No one stays inside anymore.

b) Perhaps it's time to rethink movie theater design. Perhaps the coolest architecture studio you could take right now would be one in which you rethink the contemporary cinema. Perhaps the outdoor cinemas of the future use clouds as their surface, and rooftops as their arena. AMC might even offer corporate sponsorship. From GPSFILM to CINEMA41, ideas for redesigning the cinematic experience are already out there – so how might they be tweaked to involve the sky?

c) It's the summer of 2011 – a Friday night – and you're out for drinks in Manhattan with friends. But then all the lights in midtown begin to switch off, and weird glowing shapes appear in the sky. There are noises. You think it's some kind of cheesy night club opening up downtown, or perhaps the Mayan apocalypse a year early. But then: Ghostbusters III, projected from some kind of mega-projector, appears above you in the clouds. It's the world's most talked-about film premiere: ghosts in the sky and a million unticketed viewers, in a kind of vertical philanthropy of the moving image. 3) Like something out of Archigram, you develop a stationary airship that passes up through the clouds each night to project films back down; for the audience below, it's as if a talking hologram has settled into the sky above the city. The people who control the ship are dream technicians. But then the airship is hijacked by a 15-year old, who flies it above remote stretches of the Amazon, terrifying uncontacted native tribes. Steven Spielberg soon makes a movie about him, produced by Werner Herzog. 4) BLDGBLOG here proposes FogFilms, a new project for my fellow San Franciscans. When the fog gets bad, the films get going.™ We'll transform fog banks into film screens. In any case, it seems worth asking if we could transform light pollution from its current status as a kind of abstract blur, somewhere between orange and white, into something worth watching – if we could focus it, concentrate it, or, more accurately, give it content.  [Image: Andrea Mantegna, Oculus in the Camera degli Sposi]. [Image: Andrea Mantegna, Oculus in the Camera degli Sposi].After all, there would seem to be serious architectural possibilities here. On foggy nights, or humid nights, or cloudy nights, you transform the sky into a trompe l'oeil painting, a cinematic oculus, a new ceiling, a kind of dream-valve above the city.

Don't forget that submissions for the first issue of [bracket] are due on Monday, February 2. The theme is "On Farming."  [bracket] is a collaboration between Archinect and InfraNet Lab (who I posted about last week). A description of what they're hoping to address: The first edition of [bracket] is centered around the theme of farming. Once merely understood in terms of agriculture, today information, energy, labour, and landscape, among others, can be farmed. Farming harnesses the efficiency of collectivity and community. Whether cultivating land, harvesting resources, extracting energy or delegating labor, farming reveals the interdependencies of our globalized world. Simultaneously, farming represents the local gesture, the productive landscape, and the alternative economy. The processes of farming are mutable, parametric, and efficient. From terraforming to foodsheds to crowdsourcing, farming often involves the management of the natural mediated by the technologic. Farming, beyond its most common agricultural understanding is the modification of infrastructure, urbanisms, architectures, and landscapes toward a privileging of production.

With a global food crisis looming, even the traditional farm's impact on land, resources, and economics is in need of re-visioning. Other innovations have led to a growing number of people investing in shares of a local farmer's crop, reducing trips to the supermarket and the cost of shipping food. Energy farming has seen immense diversification in the last decade with essential innovations in renewable energies such as wave farms, wind, tidal, solar, and even piezoelectrical. Submission requirements and so on are available on their website.

Sky-borne accumulations of car exhaust can cause lightning, New Scientist reports.  [Image: You bring the weather with you]. [Image: You bring the weather with you]. "In the south-eastern states," we read, a recent study showed that "lightning strikes increased with pollution by as much as 25 per cent during the working week. The moist, muggy air in this region creates low-lying clouds with plenty of space to rise and generate the charge needed for an afternoon thunderstorm." So it seems like a bit of an overstatement to say that car exhaust actually generates lightning storms, but it's nonetheless quite fascinating to think that the atmospheric conditions generated by traffic jams and congested freeways might also stimulate airborne electrical activity. Traffic jams become a kind of planetary event. You could even construct lightning highways: deliberately planned, cultivated routes of positive charge. Dubai, sick of skyscrapers (or simply bankrupted by them), instead builds itself a freeway dedicated to the electrical exploitation of the sky. On a map of global lightning strikes, it shows up as an anomalous 50km stretch across the desert, where automotive wizards of the inner atmosphere summon light from the sky. Metallica films its last music video there. But the fact that you might not only be driving within a local weather system but actually creating one as you drive just fascinates me. The weather above you is part of the traffic jam you're in; it is an epiphenomenon of urban infrastructure. Or, to re-describe climate change in a slightly more mundane way: there is so much car exhaust in the air right now that it has begun to generate its own weather.

[Image: Photo by Taylor Deupree]. [Image: Photo by Taylor Deupree].At the end of 2008, musician Taylor Deupree wrote that he would start a new project on January 1, 2009: recording one new sound a day. He explains that he "will carry a small digital audio recorder with me every day of the year and record one sound per day throughout 2009. (...) this exercise will not only force me to listen more carefully every day, but open my own sound palette, expanding into field recording." He continues, avoiding the upper-case: i will not set a time limit on each day’s recordings, but rather make each recording as long as it needs to be to capture whatever it is i’ll be capturing. along with the recorder i will carry a small notebook and make a note of date and time as well as location and "subject." After all, he concludes, "2009 will be a year of listening." The first dozen or more sounds are already up; you can listen to them at his blog. Note that you can play several files simultaneously, so it's quite interesting to move up and down the page and start different files at different times; the blog becomes a kind of musical instrument made of field recordings, used-defined audio landscapes on demand. You can listen to melting snow, a small stream, the inside of Grand Central Station, sand on the beach in Hawaii, and so on – acoustic snapshots of life on the planet. Note that Deupree is also a photographer; some of his work is really fantastic. He also once produced an album with Savvas Ysatis called Tower of Winds, inspired by the inner electronic programming of Toyo Ito's Tokyo building. [Spotted at Rare Frequency].

There's a building somewhere in New York City: every time you go there – maybe it's a bank or a department store or the office where you work – you hear what sounds like air-conditioning equipment, a distant droning noise in the background that you can't quite place.

But it's always there – maybe sometimes higher pitched than other days, but always audible.

One day, though, you happen to be there with some friends and you've got a videocamera. You're filming each other goofing off, playing in the stairwells, and so on – but when you get back home and begin to watch the video you realize it's actually quite boring. Making faces at a camera is not as interesting as you'd hoped it'd be.

So – overlooking the fact that this would not actually be possible – you begin to fast-forward the video at 4x speed, then 8x, then 16x, then 32x – and you realize, with a collective gasp, that that droning sound in the background is not a drone at all but a piece of music played slow to the point of unrecognizability. It's Beethoven, say, or Jimi Hendrix.

Someone is playing incredibly slow music, like a kind of acoustic glacier, inside the building. It's avant-garde Muzak.

You go a little crazy upon discovering this, however, and begin to make field recordings all over Manhattan, recording drones. You stand in alleys, beneath trees in Central Park, and inside abandoned warehouses, capturing ambient background sounds on tape. You visit the airport, deliberately seek out traffic jams, and illegally access basements on the Upper East Side.

And for the next six months you sit and listen to all of them at 32x speed – 64x speed, 128x speed – convinced that this world has strange music embedded in it somewhere and, if only you use your equipment right, you can find it.

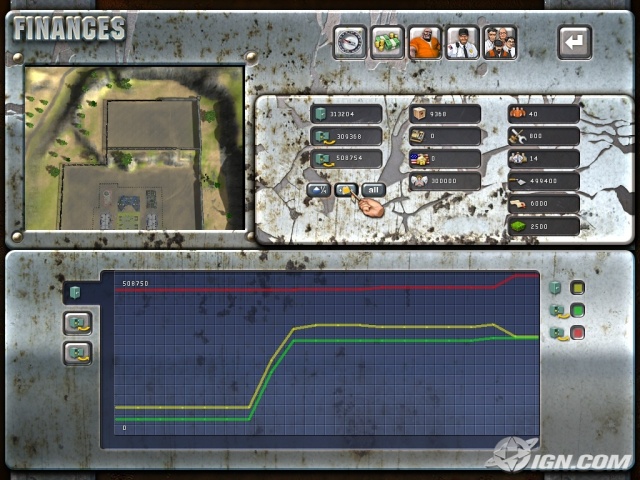

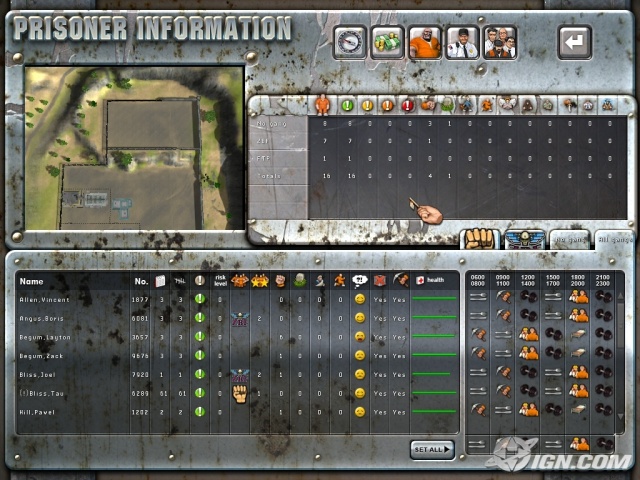

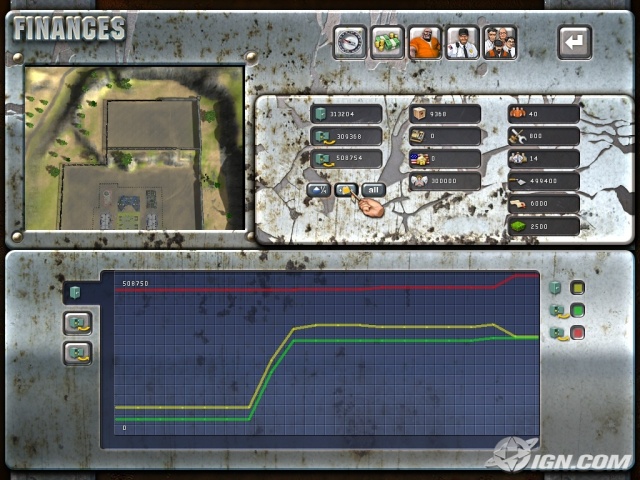

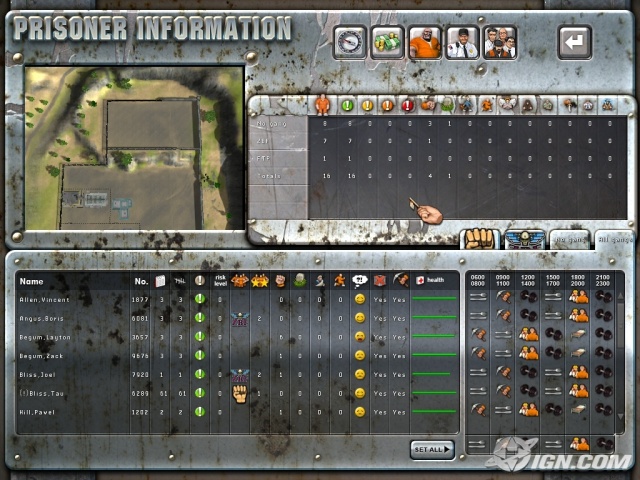

It's not exactly news, but something caught my eye the other week via Robin Sloan's Twitter feed, so I thought I'd put up a quick post about it here.  [Image: From Prison Tycoon 4: SuperMax. Image via IGN]. [Image: From Prison Tycoon 4: SuperMax. Image via IGN].The description of Prison Tycoon 4: SuperMax, a ValuSoft game released in 2008, urges players to experiment in the architectural framing and administrative implementation of prison life. "Build a profitable privately run prison from the ground up," it says. "Every wall, every fence, every decision is yours. Start small and forge your reputation as a first rate warden. Grow your facility to SuperMax capabilities, housing the most dangerous and diabolical criminals on earth – all for the bottom line." Putting moral limits on our imaginations temporarily aside, perhaps we could even conceive of Prison Tycoon 5: Guantánamo Bay, or Prison Tycoon 6: Austrian Basement Edition. Prison Tycoon 7: Gulag. Prison Tycoon 8: Escape from Abu Ghraib. Or scrap the cheap political commentary and go for sci-fi: Inflatable Prisons in Space! The final level is a siege of the earth's surface via space elevator, convicts raining down upon the planet like dark angels. The plot is loosely modeled on Paradise Lost. Setting up the next game: Prison Planet. Or famous prisons from literature – including Brian Aldiss's rotating prison of Helliconia. The Library of Babel reimagined as a SuperMax prison in the mountains of western Canada. Prisons carved from glaciers undergoing catastrophic earthquakes as global climate change causes melt-off. You have to escape before the ice sheet collapses, teaming up with the very guards who once held you captive. Prison Tycoon 10: Global Meltdown.     [Images: From Prison Tycoon 4: SuperMax. All images via IGN. If Mies van der Rohe had designed a prison, what might it have looked like?]. [Images: From Prison Tycoon 4: SuperMax. All images via IGN. If Mies van der Rohe had designed a prison, what might it have looked like?].Of course, ValuSoft kicked all of this off back in 2005 with the original Prison Tycoon: "In Prison Tycoon," we read, "you construct and maintain a private prison, hire the staff, and control the prisoners – all while trying to earn big money." But why not open the series to goals beyond "big money" and a swollen "bottom line," and aim for sheer architectural complexity? Or locational advantages, like the offshore oil rig -slash- ultramax prison in John Woo's surprisingly great film Face/Off. You construct an Alpine labyrinth that has no guards at all; the architecture itself is so bewildering that no one has ever escaped. Umberto Eco's final novel is set there; or perhaps one of his characters dreams it. Gormenghast: The Prison.   [Images: From Prison Tycoon 4: SuperMax. Images via IGN]. [Images: From Prison Tycoon 4: SuperMax. Images via IGN].However, lest you now be tempted to purchase Prison Tycoon 4, I'd first suggest reading this review. For instance: Since it's pretty much impossible to tell the difference between a guard and a prisoner in the yard, you'll have to open up the submenu. From there you click on the guard tab, select a specific guard, look at the minimap to check the whereabouts of the guard, close the submenu, investigate the most recent known whereabouts of the guard, locate and right mouse click the guy (you can't create a drag box to select anything in this game), move him into the action, right mouse click on a troubled prisoner, and select the beat-him-up icon. By the time you try to initiate all of this, a prisoner might have already died. If this all sounds convoluted it is. The whole game is like this, and it really hurts to not have a proper tutorial. Sounds like fun.

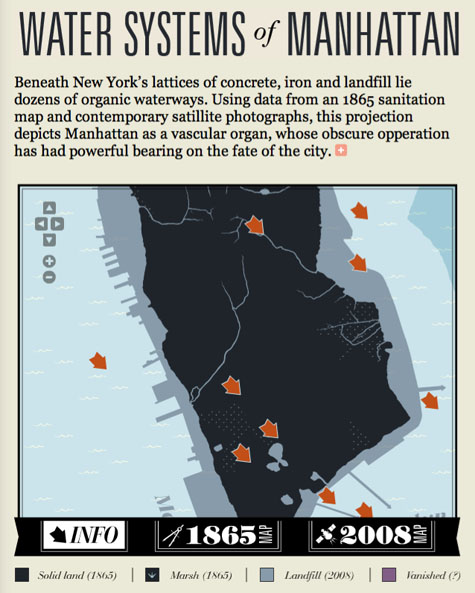

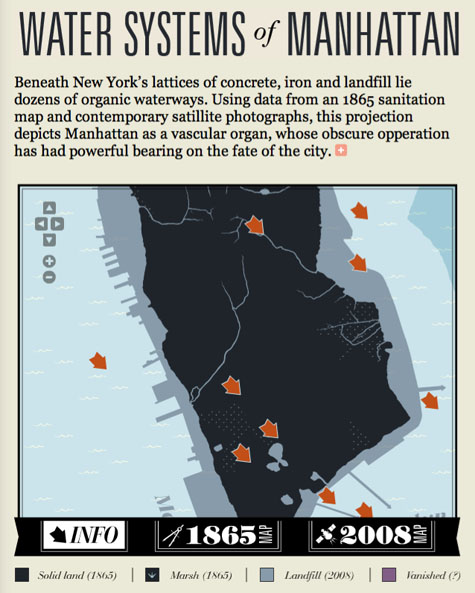

As part of their new water-themed issue, the beautifully designed New York Moon has produced this interactive map of the water systems of Manhattan.  [Image: The New York Moon's interactive map of the water systems of Manhattan; map by Zack Sultan]. [Image: The New York Moon's interactive map of the water systems of Manhattan; map by Zack Sultan]."Beneath New York’s lattices of concrete, iron and landfill lie dozens of organic waterways," they write. "Using data from an 1865 sanitation map and contemporary satillite photographs, this projection depicts Manhattan as a vascular organ, whose obscure opperation has had powerful bearing on the fate of the city." Older issues of the Moon are definitely worth checking out, including their recent look at deserts, underground acoustics, and the idea of a four-dimensional document for "investigating time and space." While you're there, don't miss the floating bog-city of Lake Titicaca: Beginning with a sturdy floating bog, and then laying a base of totora reeds over it, the men, women and children of Uros work together, piling the reeds in a different direction every two weeks until they have created a latticework strong enough to hold six or seven homes and one kitchen on each island, a process that takes about eight months. All of the forty-odd islands are then anchored to sticks pitched into the lake's floor, making the community buoyant but stationary. Though the islands at conception are about three to four feet thick, they will double over time as dying reeds are covered with newer, stiffer ones, a process of renewal repeated until it is time to build an entirely new island. Note that I hereby pitch a jointly edited future edition of New York Moon, to be curated by BLDGBLOG and Pruned, around the theme of gardens. Late summer 2009.

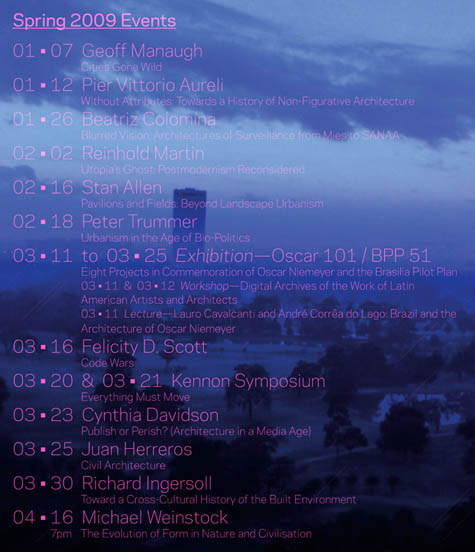

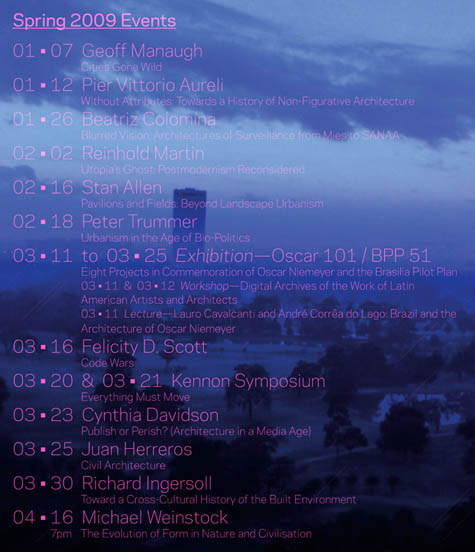

I'm excited to announce that I'll be lecturing at the Rice University School of Architecture in Houston, Texas, in only two days' time, kicking off their Spring 2009 lecture series.  [Image: View larger]. [Image: View larger].I've clearly got some very large shoes to fill with this series, however, as I've been lined up with everyone from Beatriz Colomina to Cynthia Davidson. Stan Allen, Juan Herreros, Richard Ingersoll, Pier Vittorio Aureli, Michael Weinstock, Peter Trummer – it looks like a fantastic series. For my own part, I think I've got a great talk planned – called "Cities Gone Wild" – expanding from the lecture I gave back in November, sponsored by the Complex Terrain Laboratory, at University College, London. This talk begins at 5pm on Wednesday, January 7; it's free and open to the public; and it will take place in Anderson Hall. I don't know how many readers BLDGBLOG has in Houston – or, for that matter, at Rice – but I'd love to see some of you there. And please introduce yourselves, too, as I love meeting new people. Also, at the end of my talk I hope to address the more general subject of blogging, if for no other reason than I can guarantee that there are students enrolled at Rice right now – and people living in Houston – who have something interesting to say and simply need a new platform from which to say it. I'd be happy to talk about establishing a blog and so on, as that's not a topic I've much addressed throughout all of these talks. Finally, I'll be doing thesis reviews at the architecture department all day on Thursday and Friday, so if you happen to be enrolled in the courses I'll be visiting, then cool. I look forward to meeting you! And come out to the talk – it should be fun.

|

|

[Image: From "Change of Heart: Rethinking the Prescriptive Medical Environment" by Marina Nicollier].

[Image: From "Change of Heart: Rethinking the Prescriptive Medical Environment" by Marina Nicollier]. [Image: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier].

[Image: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier]. [Image: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier].

[Image: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier]. [Image: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier; think of it as a Foucauldian application of Winston Churchill's famous phrase, that "We shape our buildings, and afterwards our buildings shape us." Only here, those buildings cause heart palpitations].

[Image: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier; think of it as a Foucauldian application of Winston Churchill's famous phrase, that "We shape our buildings, and afterwards our buildings shape us." Only here, those buildings cause heart palpitations].

[Images: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier].

[Images: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier].

[Images: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier].

[Images: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier]. [Image: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier].

[Image: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier]. [Image: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier].

[Image: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier].

[Images: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier].

[Images: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier]. [Image: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier].

[Image: From "Change of Heart" by Marina Nicollier].

[Image: The Iska Vagu stream near Hyderabad, India. "Indian factories that make lifesaving drugs swallowed by millions worldwide are creating the worst pharmaceutical pollution ever measured,"

[Image: The Iska Vagu stream near Hyderabad, India. "Indian factories that make lifesaving drugs swallowed by millions worldwide are creating the worst pharmaceutical pollution ever measured,"  [Image: The Brazilian twin town of Josef Mengele].

[Image: The Brazilian twin town of Josef Mengele]. [Image: "

[Image: " [Image: Geometry in the sky. "Diagram showing conceptual photographs of how

[Image: Geometry in the sky. "Diagram showing conceptual photographs of how  [Image: "

[Image: " [Image: The "

[Image: The " [Image: The Hanging Hotel by Takis Zenetos; think of it as the

[Image: The Hanging Hotel by Takis Zenetos; think of it as the  [Image: The Hanging Hotel, strung onto a cliffside like a musical instrument, by Takis Zenetos].

[Image: The Hanging Hotel, strung onto a cliffside like a musical instrument, by Takis Zenetos]. [Image: The Cable City of Takis Zenetos].

[Image: The Cable City of Takis Zenetos]. [Image: The Cable City of Takis Zenetos; the

[Image: The Cable City of Takis Zenetos; the

[Images: The Cable City of Takis Zenetos].

[Images: The Cable City of Takis Zenetos]. [Images: A turbined gorge by Takis Zenetos].

[Images: A turbined gorge by Takis Zenetos]. [Image: From Manhattan's Annex by W. Amanda Chin.

[Image: From Manhattan's Annex by W. Amanda Chin.  [Image: From Manhattan's Annex by W. Amanda Chin. Image slightly cropped:

[Image: From Manhattan's Annex by W. Amanda Chin. Image slightly cropped:

[Images: From Manhattan's Annex by W. Amanda Chin;

[Images: From Manhattan's Annex by W. Amanda Chin;  [Image: From the series

[Image: From the series  [Image: From the series

[Image: From the series  [Image: From the series

[Image: From the series  [Image: Andrea Mantegna,

[Image: Andrea Mantegna,  [bracket] is a collaboration between

[bracket] is a collaboration between  [Image: You bring the weather with you].

[Image: You bring the weather with you]. [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: From Prison Tycoon 4: SuperMax. Image via

[Image: From Prison Tycoon 4: SuperMax. Image via

[Images: From Prison Tycoon 4: SuperMax. All images via

[Images: From Prison Tycoon 4: SuperMax. All images via

[Images: From Prison Tycoon 4: SuperMax. Images via

[Images: From Prison Tycoon 4: SuperMax. Images via  [Image: The New York Moon's interactive map of the

[Image: The New York Moon's interactive map of the  [Image: View

[Image: View