Saddam's Palaces: An Interview with Richard Mosse

[Image: Ruined swimming pool at Uday's Palace, Jebel Makhoul, Iraq (2009); photo by Richard Mosse].

[Image: Ruined swimming pool at Uday's Palace, Jebel Makhoul, Iraq (2009); photo by Richard Mosse].Photographer Richard Mosse first appeared on BLDGBLOG last year with his unforgettable visual tour through the air disaster simulations of the international transportation industry.

He and I have since kept in touch —so, when Mosse returned from a trip to Iraq this spring, he emailed again with an unexpectedly intense, and hugely impressive, new body of work.

These extraordinary images—published here for the first time—show the imperial palaces of Saddam Hussein converted into temporary housing for the U.S military. Vast, self-indulgent halls of columned marble and extravagant chandeliers, surrounded by pools, walls, moats, and, beyond that, empty desert, suddenly look more like college dormitories. Weight sets, flags, partition walls, sofas, basketball hoops, and even posters of bikini'd women have been imported to fill Saddam's spatial residuum. The effect is oddly decorative, as if someone has simply moved in for a long weekend, unpacking an assortment of mundane possessions.

The effect is like an ironic form of camouflage, making the perilously foreign seem all the more familiar and habitable—a kind of military twist on postmodern interior design.

Of course, then you notice, in the corner of the image, a stray pair of combat boots or an abandoned barbecue or a machine gun leaned up against a marble wall partially shattered by recent bomb damage—amidst the dust of collapsed ceilings and ruined tiles—and this architecture, and the people who now go to sleep there every night, suddenly takes on a whole new, tragic narrative.

Fascinated by the dozens and dozens of incredible photos Mosse emailed—only a fraction of which appear here—I asked him to describe the experience of being a photographer in Iraq.

The ensuing dialogue appears below.

• • •

BLDGBLOG: What was the basic story behind your visit to Iraq? Was it self-funded or sponsored by a gallery?

Richard Mosse: The trip was backed by a Leonore Annenberg Fellowship in the Performing and Visual Arts, which I received after graduating from Yale last summer with an MFA in photography. The Fellowship provides enough to fund two full years of traveling to make new photographs, and I applied to shoot in a range of places, including Iraq. My proposal was to make work around the idea of the accidental monument. I'm interested in the idea that history is something in a constant state of being written and rewritten—and the way that we write history is often plain to see in how we affect the world around us, in the inscriptions we make on our landscape, and in what stays and what goes.

[Image: Saddam's heads, taken from the roof of the Republican Guard Palace, now located at Al-Salam Palace, Forward Operating Base Prosperity, Baghdad, Iraq (2009); photo by Richard Mosse].

[Image: Saddam's heads, taken from the roof of the Republican Guard Palace, now located at Al-Salam Palace, Forward Operating Base Prosperity, Baghdad, Iraq (2009); photo by Richard Mosse].I suppose it's an idea that captured me while traveling through Kosovo in 2004. I saw a building by the side of the road there that lay mined and shattered in a field of flowers. It was almost entirely collapsed—except for a church cupola which lay at a pendulous angle, though otherwise perfectly intact on a pile of rubble. It was a marvelously pictorial vision of the Kosovo Albanian desire to rewrite the history books. In other words, what I saw before me was not an act of mere vandalism, but a decisive act by the Kosovo Albanian community to disavow the fact of Serb Orthodox church heritage in the region. The removal of religious architecture is a terrible crime, and it constitutes an act of ethnic cleansing (remember Kristallnacht); yet I couldn't help but interpret this as an attempt to create a brave new Kosovo Albanian world.

I began to see architecture as something that can reveal the ways in which we alter the past in order to construct a new future, as a site in which past, present, and future come together to be reformed. And it's not the only one: language—our words and the way we use them—are another fine barometer of these things.

But architecture is something I felt I could research and portray using the dumb eye of my camera.

[Image: JDAM bomb damage within Saddam's Palace interior, Jebel Makhoul, Iraq (2009); photo by Richard Mosse].

[Image: JDAM bomb damage within Saddam's Palace interior, Jebel Makhoul, Iraq (2009); photo by Richard Mosse].BLDGBLOG: Beyond the most obvious reasons—for instance, there's a war going on—why did you go to Iraq? Was there something in particular that you were hoping to see?

Mosse: I had heard plenty about Saddam's palaces. They were the focus of the International Atomic Energy Association's tedious investigations in the years preceding the invasion, and the news was always full of delegations being turned away from this or that palace. Why were we so keen to get inside Saddam's palaces? Because he built so many—81 in total. Surely, we thought, he must be hiding something in those palace complexes. Surely he must be building subterranean particle accelerators. And, in the end, our curiosity got the better of us.

[Image: U.S.-built partition and air-conditioning units within Al-Salam Palace, Forward Operating Base Prosperity, Baghdad, Iraq (2009); photo by Richard Mosse].

[Image: U.S.-built partition and air-conditioning units within Al-Salam Palace, Forward Operating Base Prosperity, Baghdad, Iraq (2009); photo by Richard Mosse].In fact, Saddam was building palaces in every city as an expression of his authority. Palace architecture in Iraq served as a constant reminder of Saddam's immanence. A palace in your city simply fed the sense that Saddam was not just nearby—he was everywhere. Saddam was omnipresent.

I once heard a Westerner tell me that, prior to the invasion, Iraqis driving near one of Saddam's palaces would actually avert their eyes—they would refuse to look toward the palace. It was almost as if they were prisoners in a great outdoor version of Jeremy Bentham's Panopticon. Curiously, the sentry towers along the perimeter walls of Al-Salam Palace in Baghdad face only outward; they're screened from looking inward at the palace itself. People say it's so the guards could not witness Saddam's eldest son Uday's relations with underage girls, but I rather like to think that it created a sense of the unseen authoritarian staring blankly outwards. It was like those ominous black turrets that the British army constructed over the hills of Belfast, packed with listening devices and telescopic cameras.

[Image: Outdoor gym, Al-Faw Palace, Camp Victory, Baghdad, Iraq (2009); photo by Richard Mosse].

[Image: Outdoor gym, Al-Faw Palace, Camp Victory, Baghdad, Iraq (2009); photo by Richard Mosse].But the idea of Iraqis averting their eyes from Saddam's palace architecture also reminds me of something from W.G. Sebald's book On the Natural History of Destruction.

BLDGBLOG: That's an incredible book – I still can't forget his descriptions of tornadoes of fire whirling through bombed cities and melting asphalt.

Mosse: Sebald recounts how the German population, after the end of WWII, would ride the trains, staring into their laps or at the ceiling—anywhere but out the window at the terrible wreckage of their cities. It was as if they were somehow disavowing the war by willing it away, by refusing to perceive it.

It's interesting, then, that, in both instances—in both Iraq and in post-war Germany—it's the tourist, or the outsider, who observes this blindness. I suppose that's why I like to make photographs in foreign places: only the tourist notices the really dumb things that everyone else takes for granted.

[Image: U.S. military telephone kiosks built within Birthday Palace interior, Tikrit, Iraq (2009); photo by Richard Mosse].

[Image: U.S. military telephone kiosks built within Birthday Palace interior, Tikrit, Iraq (2009); photo by Richard Mosse].BLDGBLOG: The way these structures have been colonized is often amusing and sometimes shocking—the telephones, desks, and instant dormitories that turn an imperial palace into what looks like a suburban office or hospital waiting room. Can you describe some of the spatial details of these soldiers' lives that most struck you?

Mosse: It was extraordinary how some of the palace interiors had been transformed to accommodate the soldiers. Troops scurried beneath vaulted ceilings and glittering faux-crystal chandeliers. Lofty marble columns towered over rat runs between hastily constructed chipboard cubicles. Obama's face beamed out of televisions overlooking the freezers and microwaves of provisional canteen spaces.

Many of the palaces have already been handed back to the Iraqis—but where Americans troops do remain, they live in very cramped conditions, pissing into a hole in the ground and waiting days just to shower. Life is hard on the front line, and it seems more than a little surreal to be ticking off the days in a dictator's pleasure dome.

[Images: American dormitories built within Saddam's Birthday Palace, Tikrit, Iraq (2009); photos by Richard Mosse].

[Images: American dormitories built within Saddam's Birthday Palace, Tikrit, Iraq (2009); photos by Richard Mosse]. The most interesting thing about the whole endeavor for me was the very fact that the U.S. had chosen to occupy Saddam's palaces in the first place. If you're trying to convince a population that you have liberated them from a terrible dictator, why would you then sit in his throne? A savvier place to station the garrison would have been a place free from associations with Saddam, and the terror and injustices that the occupying forces were convinced they'd done away with. Instead, they made the mistake of repeating history.

This is why I've titled this body of work Breach. "Breach" is a military maneuver in which the walls of a fortification (or palace) are broken through. But breach also carries the sense of replacement—as in, stepping into the breach. The U.S. stepped into the breach that it had created, replacing the very thing that it sought to destroy.

There are other kinds of breach—such as a breach of faith, a breach of confidence, or the breach of a whale rising above water for air. All of these senses were important to me while working on these photographs.

[Image: Provisional office wall partitions within Al-Faw Palace, Camp Victory, Baghdad, Iraq (2009); photo by Richard Mosse].

[Image: Provisional office wall partitions within Al-Faw Palace, Camp Victory, Baghdad, Iraq (2009); photo by Richard Mosse]. BLDGBLOG: In several of these photos, the soldiers are literally lifting tiles up from the floor as if the buildings had been left unfinished, or they're peering through cracks in the palace walls. From what you could see, were Saddam's palaces badly constructed or were they just heavily damaged during the war?

Mosse: Tiles simply fell from Al-Faw Palace because the cement used there had been poorly salinated. If that can happen to tiles, think what's happening when the entire palace has been built on similarly salinated foundations! It's just a matter of time before Al-Faw collapses in on itself.

You can already see arches cracking and walls beginning to sag.

[Image: Fallen tiles and chandeliers, Al Faw Palace, Camp Victory, Baghdad, Iraq (2009); photo by Richard Mosse].

[Image: Fallen tiles and chandeliers, Al Faw Palace, Camp Victory, Baghdad, Iraq (2009); photo by Richard Mosse]. But I'm reluctant to include images of U.S. soldiers pointing out problems with Saddam's architecture, because it's fairly evident that those could be a form of propaganda—and it's easy to forget that many of these palaces were built during times of terrible sanctions imposed by the West. It might not seem very clear why Saddam was busy building palaces in a time of sanctions, but remember how the WPA was set-up during the Great Depression? I don't want to risk being called an apologist for Saddam, but there are many ways to read a story.

[Image: "Thank you for your service" banner, Al-Faw Palace interior, Camp Victory, Iraq (2009); photo by Richard Mosse].

[Image: "Thank you for your service" banner, Al-Faw Palace interior, Camp Victory, Iraq (2009); photo by Richard Mosse]. That said, the palace is a fabulous monument to rushed construction, poor materials, and gaudy pomp. Saddam had apparently insisted that the palace be finished within two years, so many shortcuts were taken during construction. For example, the stairway banisters were made of crystallized gypsum—rather than carved marble—and where pieces didn't quite fit together, they were just sanded down rather than replaced. Marble that was used in the palace (such as in the great spacious bathrooms) was imported from Italy, in spite of the trade embargo. And the plaster cast frescoes in the ceilings were imported from Morocco.

[Image: Stairway, Al-Faw Palace, Camp Victory, Baghdad, Iraq (2009); photo by Richard Mosse].

[Image: Stairway, Al-Faw Palace, Camp Victory, Baghdad, Iraq (2009); photo by Richard Mosse]. Al-Faw Palace later became the U.S, Army's Command HQ, located at the heart of Camp Victory, near Baghdad International Airport. The palace is now teeming with generals, including General Odierno, the commander of coalition forces in Iraq. It's a great, tiered wedding-cake structure, built around an inner hall with possibly the biggest and ugliest chandelier ever made. In fact, the chandelier is not made of crystal, but from a lattice of glass and plastic.

[Image: Chandelier, Al-Faw Palace, Camp Victory, Baghdad, Iraq (2009); photo by Richard Mosse].

[Image: Chandelier, Al-Faw Palace, Camp Victory, Baghdad, Iraq (2009); photo by Richard Mosse].The palace itself is then surrounded by a lake, which seems a bit like a moat—and it would be tempting to take a swim there, but the moat has been turned into a standing pool for Camp Victory's sewage. In the summer, the place must be rather unpleasant: rank in all senses of the word, both military and sanitary. These artificial lakes surrounding the palace are also populated by the infamous "Saddam Bass." It's said that Saddam would feed the bodies of his political opponents to these monsters. In fact, they're not bass at all, but a breed of asp fish. U.S. troops stationed at Camp Victory love to fish on these lakes, and a 105-pound specimen was recently caught.

[Image: Tigris Salmon caught at Camp Victory Base, measuring 5 feet 10.5 inches and weighing 105 lbs. Image courtesy of the U.S. Army].

[Image: Tigris Salmon caught at Camp Victory Base, measuring 5 feet 10.5 inches and weighing 105 lbs. Image courtesy of the U.S. Army].BLDGBLOG: How was your own presence received by those soldiers? Did you present yourself as a photojournalist or as an art photographer?

Mosse: The difference between art and journalism is, for me, of paramount importance—but twenty minutes in Iraq, and the dialectic recedes. I got a vague sense that Americans working there feel a little forgotten—unappreciated by people at home—so they're very grateful for a camera, any camera, coming through. Even a big 8"x10" bellows camera with an Irishman in a cape. There were a lot of rather obvious photographs that I chose not to make, and occasionally someone got offended by this.

[Image: A game of basketball, Birthday Palace, Tikrit, Iraq (2009); photo by Richard Mosse].

[Image: A game of basketball, Birthday Palace, Tikrit, Iraq (2009); photo by Richard Mosse]. BLDGBLOG: What was the soldiers' opinion of these buildings? Did they ever just wander around and explore them, for instance, or was that a safety violation?

Mosse: I got the feeling that soldiers who occupied one of Saddam's palaces were pretty interested in its original function. They seemed a lot more together, and happier with their job, compared with the troops I met on the massive, sprawling, purpose-built military bases in the Iraqi desert. Constant reminders of hierarchy and protocol were everywhere on the bigger bases—but on the more cramped and less comfortable palace bases, soldiers of different ranks seemed much closer and more capable of shooting the shit with each other, to borrow an American turn of phrase.

Though a far tougher environment, there seemed to be real job satisfaction—a sense that they were taking part in a piece of history.

[Image: Detail of U.S. soldier's living quarters, Birthday Palace interior, Tikrit, Iraq (2009); photo by Richard Mosse].

[Image: Detail of U.S. soldier's living quarters, Birthday Palace interior, Tikrit, Iraq (2009); photo by Richard Mosse]. BLDGBLOG: Architect Jeffrey Inaba once joked, in an interview with BLDGBLOG, that Saddam's palaces look a bit like McMansions in the suburbs of New Jersey. He quipped that "the architecture of state power and the architecture of first world residences don’t seem that far apart. Saddam’s palaces, while they’re really supposed to be about state power, look not so different from houses in New Jersey." They're not intimidating, in other words; they're just tacky. They're kitsch. Now that you've actually been inside these palaces, though, what do you think of that comparison?

Mosse: Well, I've never been inside a New Jersey McMansion, so I can't pass judgment. However, "McMansion" is a term borrowed by us in Ireland, where I'm from. Ireland was hard-hit by English penal laws, from the 17th century onward. One of those laws was the Window Tax. This cruel levy was imposed as a kind of luxury tax, to take money from anyone who had it; the result was that Irish vernacular architecture became windowless. The Irish made good mileage on the half-door, for instance, a kind of door that can be closed halfway down to keep the cattle out but still let the light in.

Aside from this innovation, and from subtleties in the method of thatching, Irish architecture never fully recovered—to the point that, even today, almost everyone in my country chooses their house from a book called Plan-a-Home, which you can buy for 15 euros. And if you have extra cash to throw in, you can flick to the back of the book and choose one of the more spectacular McMansions. Those are truly Saddam-esque.

[Image: Birthday Palace, Tikrit, Iraq (2009); photo by Richard Mosse].

[Image: Birthday Palace, Tikrit, Iraq (2009); photo by Richard Mosse]. BLDGBLOG: Finally, the "Green Zone," as well as many of these palaces, are notoriously insular, cut-off behind security walls from the rest of Iraq. Did you actually feel like you were in Iraq at all—or in some strange architectural world, of walls and dormitories, surrounded by homesick Americans?

Mosse: Not all of Saddam's palaces are as isolated from reality as those situated in the green zone (or international zone, as it's now called). One I visited near Tikrit—Saddam's Birthday Palace—was even right at the heart of the city. Saddam was said to visit the palace each year on his birthday.

Wherever you go on the base, you're eminently shootable—a fantastic sniper target—and can hear the coming and going of Iraqis in the surrounding neighborhoods. It's a remarkable experience to go up to the roof with the pigeons at dusk and watch the changing light. You get a palpable impression of the great tragedy of the Iraq war, and you can see for yourself the fencing between neighborhoods, the rubbish strewn everywhere, the emptiness of the place, and you can hear the packs of dogs baying about. But you can also hear occasional shots fired in the distance, and you get the distinct feeling that you're being watched.

I spent a very slow month in Iraq trying to reach as many of these palaces as possible. I only managed to visit six out of eighty-one palaces. It is impossibly slow going over there, working within the war machine. These palaces are currently being handed back to the Iraqis, and many of them will be repurposed, sold to private developers or demolished. If I could get the interest of a publisher, for instance, I would return to Iraq to complete the project before Saddam’s heritage, and the traces of U.S. occupation, are entirely removed.

• • •

Thanks again to Richard Mosse for the incredible opportunity to talk to him about this trip, and for allowing BLDGBLOG to publish these images for the first time.

Be sure to see the rest of Mosse's work on his website. Hopefully the entirety of Breach will be coming soon to a book or gallery near you.

[Image:

[Image:  [Image: Detail of a zoning map for

[Image: Detail of a zoning map for  [Image: A Tribute to Sir Christopher Wren (1838) by

[Image: A Tribute to Sir Christopher Wren (1838) by  [Image: The Professor's Dream (1848) by Charles Robert Cockerell, courtesy of the

[Image: The Professor's Dream (1848) by Charles Robert Cockerell, courtesy of the

[Images: The Professor's Dream (1848), and several details thereof, by Charles Robert Cockerell, courtesy of the

[Images: The Professor's Dream (1848), and several details thereof, by Charles Robert Cockerell, courtesy of the  [Image: The

[Image: The

[Images: From Ian Douglas-Jones's awesome

[Images: From Ian Douglas-Jones's awesome  And, lo! In a moment of brief mania, I saw that The BLDGBLOG Book is right there on

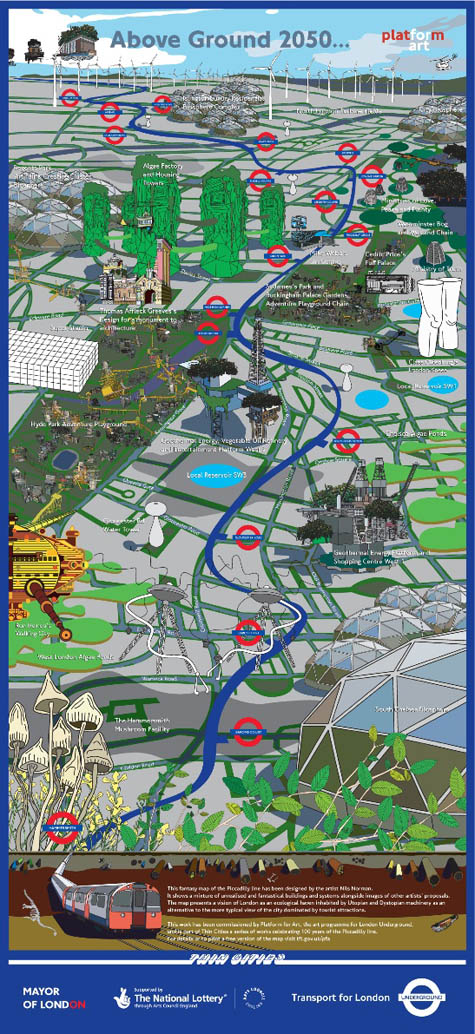

And, lo! In a moment of brief mania, I saw that The BLDGBLOG Book is right there on  [Image: "Above Ground" by

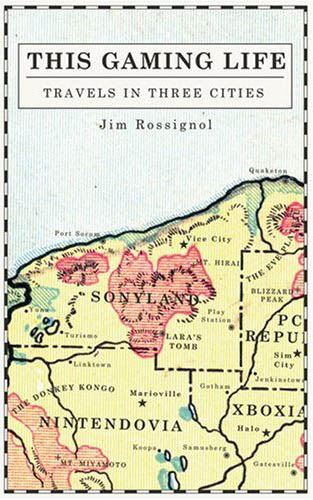

[Image: "Above Ground" by  [Image: Jim Rossignol's

[Image: Jim Rossignol's  [Image: A scene from

[Image: A scene from  [Image: From

[Image: From

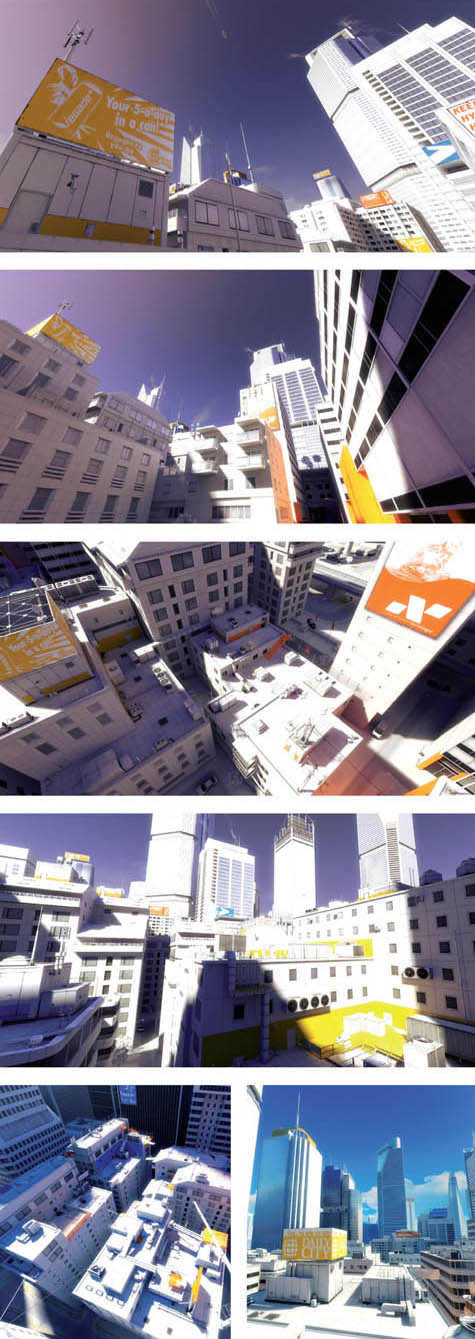

[Images: Scenes from

[Images: Scenes from  [Image: A scene from Love by

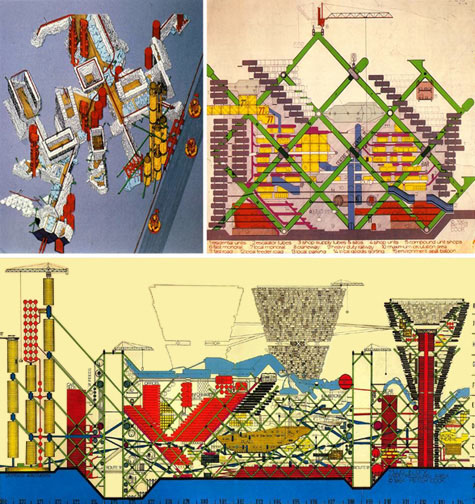

[Image: A scene from Love by  [Image: Plug-In City by

[Image: Plug-In City by  [Image: A geological rethinking of

[Image: A geological rethinking of  [Image: The architecture of

[Image: The architecture of