Geothermal Gardens and the Hot Zones of the City

[Image: "Reykjavik Botanical Garden" by Andrew Corrigan and John Carr].

[Image: "Reykjavik Botanical Garden" by Andrew Corrigan and John Carr].In a fantastic issue of AD, edited by Sean Lally and themed around the idea of "Energies," a long list of projects appeared that are of direct relevance to the Glacier/Island/Storm studio thread developing this week. I want to mention just two of those projects here.

[Image: "Reykjavik Botanical Garden" by Andrew Corrigan and John Carr].

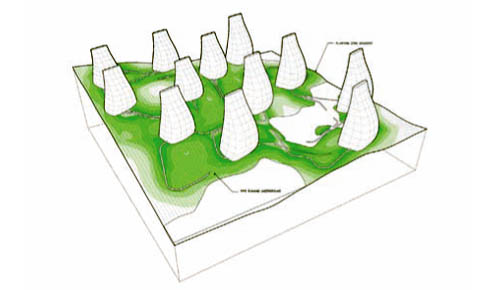

[Image: "Reykjavik Botanical Garden" by Andrew Corrigan and John Carr].For their "Reykjavik Botanical Garden," Rice University architecture students Andrew Corrigan and John Carr proposed tapping that city's geothermal energy to create "microclimates for varied plant growth."

"Heat is taken directly from the ground," they write, "and piped up across the landscape into a system of [pipes and] towers."

- Zones of heat radiate out from the pipes, creating a new climate layer with variable conditions based on their number and proximity to each other. These exterior plantings are mostly native to Iceland, but the amplified environment allows a wider range of growth than would normally be possible, informing the role and opportunity of this particular botanical garden. Visitors experience growth never before possible in Iceland, and travel through new climates throughout the site.

[Image: "Reykjavik Botanical Garden" by Andrew Corrigan and John Carr].

[Image: "Reykjavik Botanical Garden" by Andrew Corrigan and John Carr].The climate of the city is altered, in other words, literally from the ground up; using the functional equivalent of terrestrially powered ovens, otherwise botanically impossible species can healthily take root.

This domestication of geothermal energy, and the use of it for purposes other than electricity-generation, raises the fascinating possibility that heat itself, if carefully and specifically redirected, can utterly transform urban space.

[Image: Produced for the "Vatnsmyri Urban Planning Competition" by Sean Lally, Andrew Corrigan, and Paul Kweton of WEATHERS].

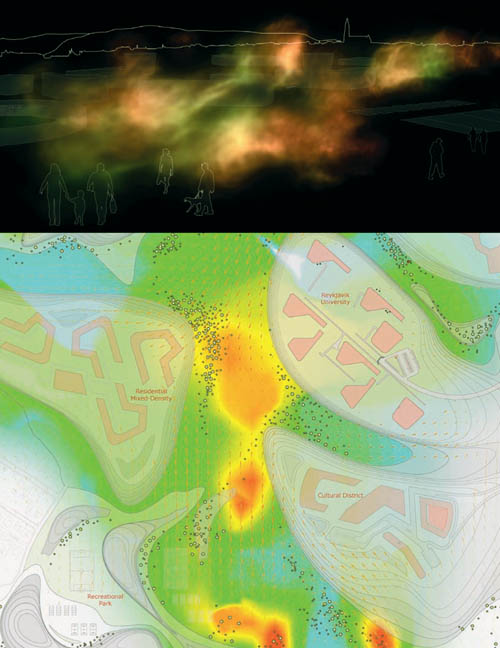

[Image: Produced for the "Vatnsmyri Urban Planning Competition" by Sean Lally, Andrew Corrigan, and Paul Kweton of WEATHERS].A variant on this forms the basic idea behind Sean Lally's own project, produced with Andrew Corrigan and Paul Kweton, for the Vatnsmyri Urban Planning Competition (a competition previously discussed on BLDGBLOG here).

Their design also proposes using geothermal heat in Reykjavik "to affect the local climatic conditions on land, including air temperature and soil temperature for vegetative growth." But their goal is to generate a "climatic 'wash'"—that is, an amorphous zone of heat that lies just slightly outside of direct regulation. This slow leaking of heat into the city could then effect a linked series of hot zones—or variable microclimates, as the architects write—that would punctuate the city with thermal oases.

Like a winterized inversion of the air-conditioned cold fronts we feel rolling out from the open doors of buildings all summer long, this would be pure heat—and its attendant humidity—roiling upward from the Earth itself. The result would be to generate a new architecture not of walls and buildings but of temperature thresholds and bodily sensation.

Indeed, as David Gissen suggests in his excellent book Subnature, this project could very well imply "a new form of urban planning," one in which sculpted zones of thermal energy take precedence over architecturally designated public spaces.

Of course, whether this simply means that under-designed urban dead zones—like the otherwise sorely needed pedestrian parks now scattered up and down Broadway—will be left as is, provided they are heated from below by a subway grate, remains, for the time being, undetermined.

This is all just part of a much larger question: how we "renegotiate the relationship between architecture and weather," as Jürgen Mayer H. and Neeraj Bhatia, editors of the recent book -arium: Weather + Architecture, describe it. The Glacier/Island/Storm studio will continue to explore these and other abstract questions of climate and architectural design throughout the spring.

Comments are moderated.

If it's not spam, it will appear here shortly!

This is an incomplete thought, but I feel like there is resonance here with Iceland's quest to become the world's data haven. The main problem faced by server farms is cheap power, and much of that power goes to simply cooling the machines. Iceland's geothermal energy promises much cheap power and its cold weather promises much less cooling.

It's not hard to imagine an interplay of server farms and the ideas you present here. Islands of heat, generated by geothermal running and heating computers, that radiate the heat into plants and microclimes. Icelanders can literally feel the warming of their economy as new servers come online.

Tim, that sounds not dissimilar from this plan, which I've been meaning to blog about for months now, in which "500 Helsinki homes [would] be heated by cathedral's underground servers": "Helsinki's Uspenski Cathedral's data center... will use its overheating servers to warm 500 homes joined by a network of pipes."

Tim thanks for linking the article on Iceland; it’s helpful to my project. I’m researching the potentials of artificial glaciation for server cooling…

I agree; the steady output from servers could possibly create a more reliable environment for plant growth rather than a community of towers siphoning heat from the ground with more variable conditions. I’ve always been interested in the obscure relationships between program functions and how they can feed off of each other in which the server-plant relationship potentially could.

Maybe if it was a sugar company that stored all of its company data in a server farm using the heat to create the ideal growing conditions to grow cane and burned the bio-waste in turn for energy to run the servers - hahaha

The implications of this kind of thinking are incredible, and frightening. I am worried that it will increase energy consumption...as the stuff of 'spillage' becomes desirable.

I also just read Sloterdijk's book on atmoterrorism, which makes taking these kinds of projects seriously a bit problematic. They become ideal sites for administration and biopower.

Post a Comment