House-in-a-House Museum

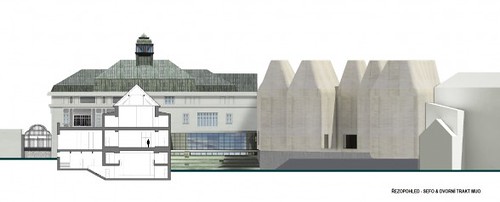

[Image: Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti].

[Image: Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti].I'm a fan of this strangely megalithic museum and cultural center made from a series of concrete shells, colored white with crushed marble, proposed for the Czech city of Olomouc.

According to the designers, Šépka Architekti, the project "attempts to draw inspiration from both... a small scale of mediaeval subdivision of land on the one hand and the large scale of palaces, ecclesiastical and military buildings of the Předhradí beginning here on the other."

[Image: Sketch of the Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti, looking vaguely like an inverted, institutional-scale variation on Neil Denari's Useful and Agreeable House].

[Image: Sketch of the Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti, looking vaguely like an inverted, institutional-scale variation on Neil Denari's Useful and Agreeable House].The museum is divided into five apparently separate but linked buildings; this is due to "the necessary separation of the individual functions of the exhibition halls, library, entry hall or bookshop and refreshments," a "necessary separation" that also generates a convenient spatial identity for the overall project.

One of the coolest things about the design, though, is what Šépka Architekti call their "house in a house" idea, inspired by access to indirect sunlight: "Even in the cases when an upper floor is inserted in an individual building, daylight is ensured on the lower floor through placement of a smaller structure. We thus approach the topic of a ‘house in a house’, which ensures favourable conditions for the the display of exhibits on the walls while providing light from above on both floors."

You can see the formal implications of this in the below image, where a massive, seemingly hovering trapezoid acts both as another, elevated room for gallery use and as a massive, light-filtering device for the skylights further above.

[Image: Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti].

[Image: Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti].It's a mass that casts shadows inside the building.

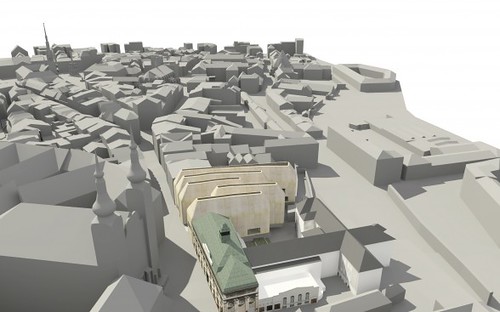

Provided the exterior concrete ages well, the museum's fivefold street presence—briefly stepping back at one point to form a public plaza—is actually pretty stunning. It manages to allude to design languages as diverse as Neo-Brutalism, the Romanesque, a kind of Tatooine Moderne, and computer harddrive casings (although I'm reminded of Owen Hatherley's recent quip about "a modernised classicism, monumental yet free in details, that usually gets subsumed under the meaningless retrospective coinage 'art deco'"—here, we might say, "modern geometries, imposing in size, built from concrete, and thus subsumed under the meaningless retrospective coinage 'Neo-Brutalism'").

[Image: Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti].

[Image: Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti].The results are quite beautiful in profile, even when simply rising up behind the walls of neighboring buildings.

In any case, the interior volumes also lend themselves well to defining an overall spatial experience, even while departing from one another just enough to keep each bay or gallery distinct.

[Image: Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti].

[Image: Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti].As mentioned earlier, that interior is a mix of art galleries, a library, a bookshop/cafe, performance spaces, and, oddly enough, as if Photoshopped in simply to prove a point, a basketball court. Note that the stadium seating visible in many of these images has been mounted on rails for ease of rearrangement.

[Image: Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti].

[Image: Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti].In plan, it's interesting to remember that the separate units of the building here were generated from what Šépka Architekti referred to as the "small scale of mediaeval subdivision of land." In other words, the buildings take their formal cue—at least abstractly—from ancient real estate divisions on the ground in Olomouc, not from some overzealous application of the architects' own stylized form of site analysis.

[Image: Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti].

[Image: Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti].The complete building, seen in slices:

[Image: Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti].

[Image: Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti].Further, the "small scale of mediaeval subdivision of land" that I've mentioned three times now also means that what could very easily be an imposing, alien monolith made from smooth white concrete, stuck irresponsibly in the center of the city, actually manages to be appropriate in scale.

[Image: Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti].

[Image: Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti].The building hasn't been constructed, of course, and we have no real idea how the concrete will age; but I was struck by the images from the instant I saw them, flipping through a back issue of a10 yesterday afternoon.

Check out more images courtesy of Šépka Architekti.

Comments are moderated.

If it's not spam, it will appear here shortly!

The image of the courtyard reminds me of the VERY similar patio of Museum M in Leuven, Belgium. (Picture)

maybe architecturally clever but GOD that thing is horrendous... no offense to the architects but this needs to be put into a completely different environment, not next to those early-20th century/late 19th buildings IMO.

I like the concept and the height seems to fit with the surrounding buildings but the facade and bulk are "brutal."

this is some of the most formally beautiful architecture I have seen; the simplicity of the layout is inspiring and the perfectly balanced combination of the curvature and the geometric nature of the walls is striking and peacful. Well done Sepka Architekti

quite horrible. like a nightmare one hopes to wake up from

Milk bottles.

This would be a blight on the cityscape, among those beautiful ornate 19th century facades. No amount of architectural pretentiousness would cover that up. I don't understand why public buildings have to be so ugly nowadays. One can build a modern functional building with "old-fashioned" design sensibilities. I look at 19th and early 20th century (pre-WWII) architecture and I find it pleasing to the eye and well-designed. Things were...pretty. Is that so wrong? I am so tired of these weird modernistic monoliths that architects always seem to propose, and often build. No matter how innovative they are, who do they serve? Is anybody happy, or comfortable in the space? What does it really say about our society when we build such things?

Post a Comment