Tunnel to Nowhere

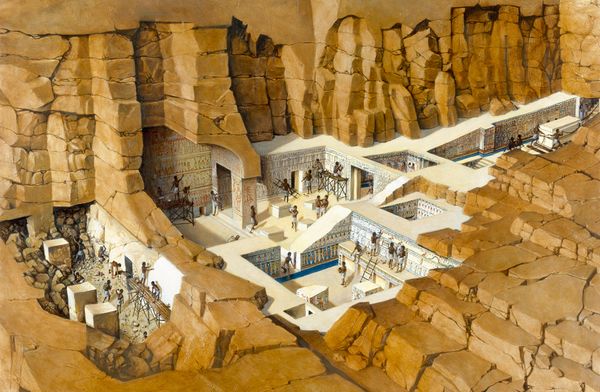

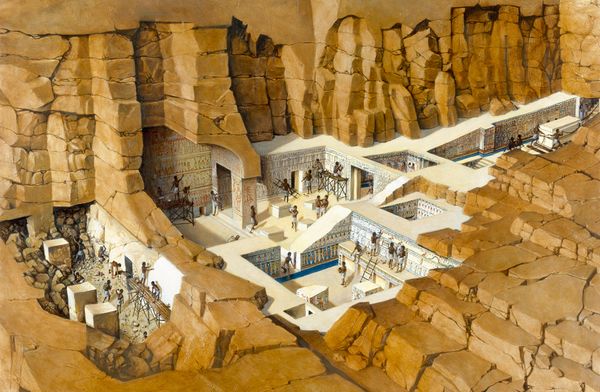

I'm enamored with this cutaway diagram, by Christopher Klein of National Geographic, depicting Egypt's so-called "tunnel to nowhere."

[Image: A cutaway of Seti's tomb by Christopher Klein, courtesy of National Geographic].

[Image: A cutaway of Seti's tomb by Christopher Klein, courtesy of National Geographic].

In fact, it is a "mysterious tunnel that links the ancient tomb of Pharaoh Seti I to ... nothing."

That the sprawling tunnelwork would eventually lead—it seems—to nowhere was not a credible option at the start of these recent explorations: "The ancient Egyptians never built something without a plan," we read back in 2008, "without an aim or a target to do this, so I think this tunnel will lead to something important."

On the other hand, it's an interesting additional detail that this particular pharaoh was called Seti.

Returning to Klein's image, it would be amazing to see his take on, say, the entire New York subway system, its tunnels drilled through bedrock, or a cutaway diagram drawn by Klein, explaining the underground nuclear waste storage facilities at Yucca Mountain (or, for that matter, at Onkalo). Or, why not, a weird hybrid of all three: a pharaonic tomb crossed with a densely packed urban subway system that eventually leads, after thousands of loops and coils, to some throbbing subterranean underworld stacked with Dantean spirals of nuclear waste.

(Via Archaeology).

[Image: A cutaway of Seti's tomb by Christopher Klein, courtesy of National Geographic].

[Image: A cutaway of Seti's tomb by Christopher Klein, courtesy of National Geographic].In fact, it is a "mysterious tunnel that links the ancient tomb of Pharaoh Seti I to ... nothing."

- After three years of hauling out rubble and artifacts via a railway-car system, the excavators have hit a wall, the team announced last week. It seems the ancient workers who created the steep tunnel under Egypt's Valley of the Kings near Luxor abruptly stopped after cutting 572 feet (174 meters) into rock.

That the sprawling tunnelwork would eventually lead—it seems—to nowhere was not a credible option at the start of these recent explorations: "The ancient Egyptians never built something without a plan," we read back in 2008, "without an aim or a target to do this, so I think this tunnel will lead to something important."

On the other hand, it's an interesting additional detail that this particular pharaoh was called Seti.

Returning to Klein's image, it would be amazing to see his take on, say, the entire New York subway system, its tunnels drilled through bedrock, or a cutaway diagram drawn by Klein, explaining the underground nuclear waste storage facilities at Yucca Mountain (or, for that matter, at Onkalo). Or, why not, a weird hybrid of all three: a pharaonic tomb crossed with a densely packed urban subway system that eventually leads, after thousands of loops and coils, to some throbbing subterranean underworld stacked with Dantean spirals of nuclear waste.

(Via Archaeology).

Comments are moderated.

If it's not spam, it will appear here shortly!

I am also enamored with this cutaway diagram! I recently visited Palatine Hill in Rome (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Palatine_hill) and have been craving a visceral cutaway diagram showing the caves, palaces, villas and other dwellings that are built into it...

At the time of Seti's death, Ancient Egyptians believed that the afterlife did in fact exist underground, and that these elaborate tombs were the dead Pharaoh's pathway to get there. While Seti I's is the longest, there are many tombs in the King's Valley that feature similar pathways and downward staircases that eventually lead to nothing. It was believed that by the time the dead Pharaoh ventured to these points, he would be able to pass through the stone walls that existed in front of him to journey deeper into the ground.

Alternative explanation: they ran out of money (or, if they didn't use money, slaves or food for the slaves or whatever).

Post a Comment