Hives and valves, filters and membranes

[Image: Detailed view of Hylozoic Ground's "Protocell" assembly; courtesy of Philip Beesley Architect].

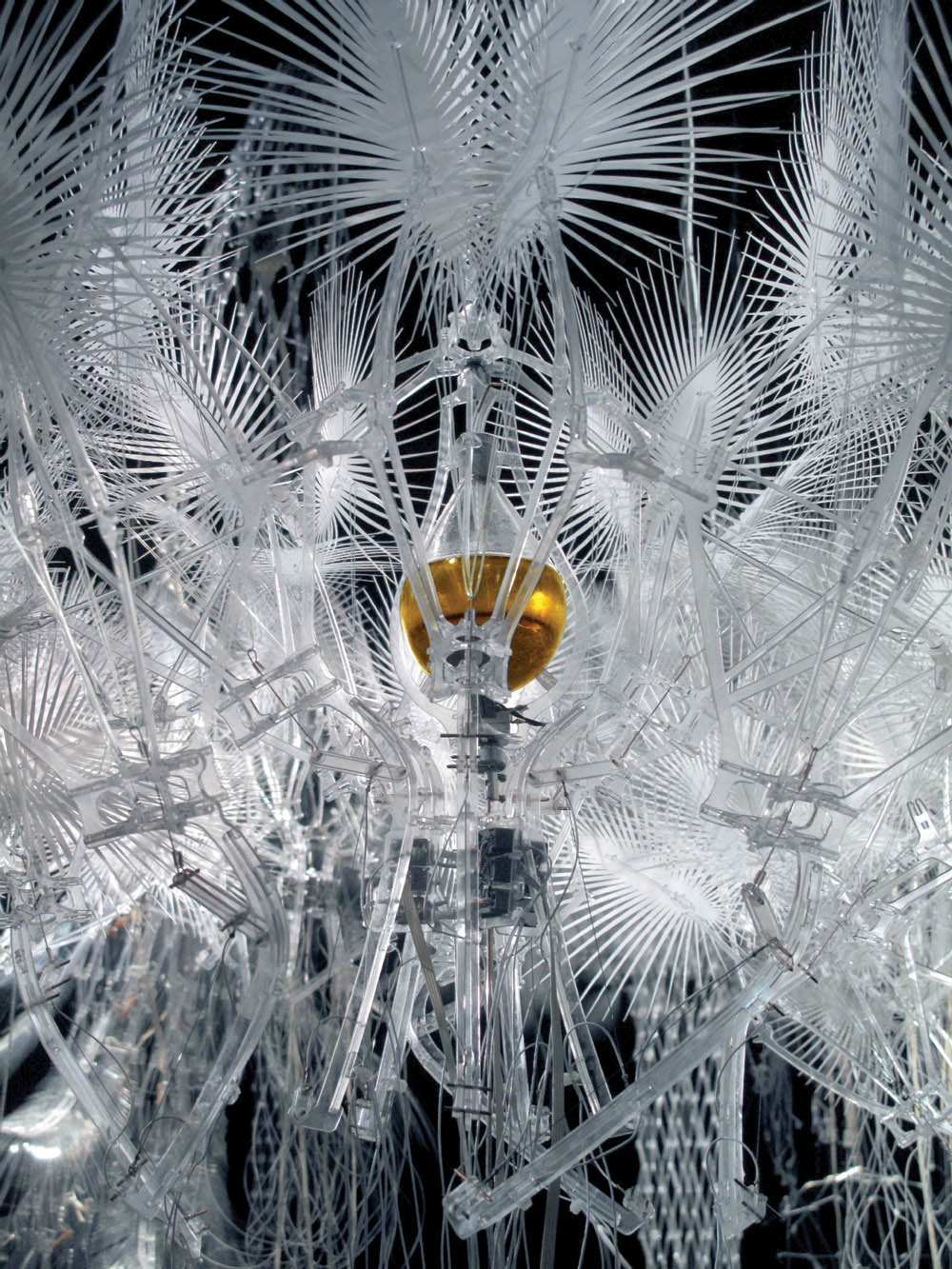

[Image: Detailed view of Hylozoic Ground's "Protocell" assembly; courtesy of Philip Beesley Architect].Philip Beesley's Hylozoic Ground installation opens this coming Friday at the Venice Biennale, where it is installed inside the Canadian pavilion. It is a "suspended geotextile that gradually accumulates hybrid soil from ingredients drawn from its surroundings."

As Beesley explains, "Hylozoic Ground is an immersive, interactive environment that moves and breathes around its viewers... Next-generation artificial intelligence, synthetic biology, and interactive technology create an environment that is nearly alive." Indeed, he adds, "hylozoism is the ancient belief that all matter has life."

[Image: Detail from Hylozoic Ground; courtesy of Philip Beesley Architect].

[Image: Detail from Hylozoic Ground; courtesy of Philip Beesley Architect].Part of this artificial life comes from the "intricate lattice of small transparent acrylic meshwork links" that make up the project, as well as the "network of interactive mechanical fronds, filters and whiskers" that form its periphery. Together, these allow the installation's edges to "arch uncannily towards those who venture into its midst, reaching out to stroke and be stroked like the feather or fur or hair of some mysterious animal."

[Image: Detail from Hylozoic Ground; courtesy of Philip Beesley Architect].

[Image: Detail from Hylozoic Ground; courtesy of Philip Beesley Architect].The resulting structure is "similar to a coral reef, following cycles of opening, clamping, filtering and digesting. Arrays of touch sensors create waves of diffuse breathing motion, luring visitors into the shimmering depths of a forest of light."

- Akin to the functions of a living system, embedded machine intelligence allows human interaction to trigger breathing, caressing, and swallowing motions and hybrid metabolic exchanges. These empathic motions ripple out from hives of kinetic valves and pores in peristaltic waves, creating a diffuse pumping that pulls air, moisture and stray organic matter through the filtering Hylozoic membranes. "Living" chemical exchanges are conceived as the first stages of self-renewing functions that might take root within this architecture.

[Image: Detail from Hylozoic Ground; courtesy of Philip Beesley Architect].

[Image: Detail from Hylozoic Ground; courtesy of Philip Beesley Architect].There is also an accompanying book coming out in time for the Biennale, and I'm excited to say that I've got a short essay in it; it also includes texts by Rachel Armstrong, Detlef Mertins, Neil Spiller, and many more, and it explores the various architectural, scientific, and technical implications of Beesley's work.

Briefly, as I suggest in my own essay, Beesley's work deserves a much wider audience than architectural Biennales. Living geotextiles that double as soil-producing landscapes—that is, they create their own biomass—these would not even be out of place in conversations about experimental agriculture and even large-scale terraforming.

If Mars, for instance, as we read earlier this week, is actually "ideally suited for crop farming," then I can easily see how a massive, self-unfolding custom geotextile, designed by Philip Beesley, could origami itself out from a NASA landing pod and begin the generations-long process of making another planet habitable for terrestrial life (there are, of course, very clear moral and biochemical objections to the idea of spreading Earthly life beyond our planet, but I am willfully overlooking those right now).

[Image: NASA/KSC Mars Greenhouse Project].

[Image: NASA/KSC Mars Greenhouse Project].If the above image, released by the Mars Greenhouse Project to illustrate the possibilities of offworld agriculture, instead depicted Beesley's Hylozoic Soil sprouting hives, valves, filters, and membranes to form a future living system, then perhaps the hidden value of these sorts of architectural experiments might be revealed.

In any case, if you're in Venice this week, stop by the opening of Hylozoic Ground at the Biennale.

Comments are moderated.

If it's not spam, it will appear here shortly!

Or (and hi Geoff, this blog blows my mind at least twice daily since I was intorduced to it, so thanks and keep going), on the terrestrial side and in the future, perhaps because of global warming, perhaps because of overused land, perhaps because of human violence, we may have need of the descendants of this project in order to revitalize blasted, parched, and polluted areas of the earth, or even just of a neighborhood. Drop the package in the middle of the fallout zone and open the box remotely. The "machine" unwrinkles itself slowly, like a fast-forward video of a field of ferns emerging, and wait a few decades to go in there and remove the portion of the machine which has ingested all the toxic material, the giant lung with its great breath, waiting to exhale into the big bag out in distant orbit, that gargantuan off-planet holding cell. After removal, start planting in the churned and mixed earth. All the good stuff is still here.

Deliver the machine to the glass and trash strewn empty city lot, wait three months and return to see that it has assembled itself into a tree whose branches hold up every stray glint of glass and every scrap of non bio-degradable trash. Empty the tree of the first load and return as often as needed.

Paul, thanks! Those are fantastic ideas.

Using Beesley's work to remediate contaminated landscapes is actually something else I mention in my essay for the forthcoming book; there is so much potential for these outside the art gallery, and I would really love to see some of those other uses explored.

Post a Comment