The Permission We Already Have

[Image: Courtesy of David Knight and Finn Williams].

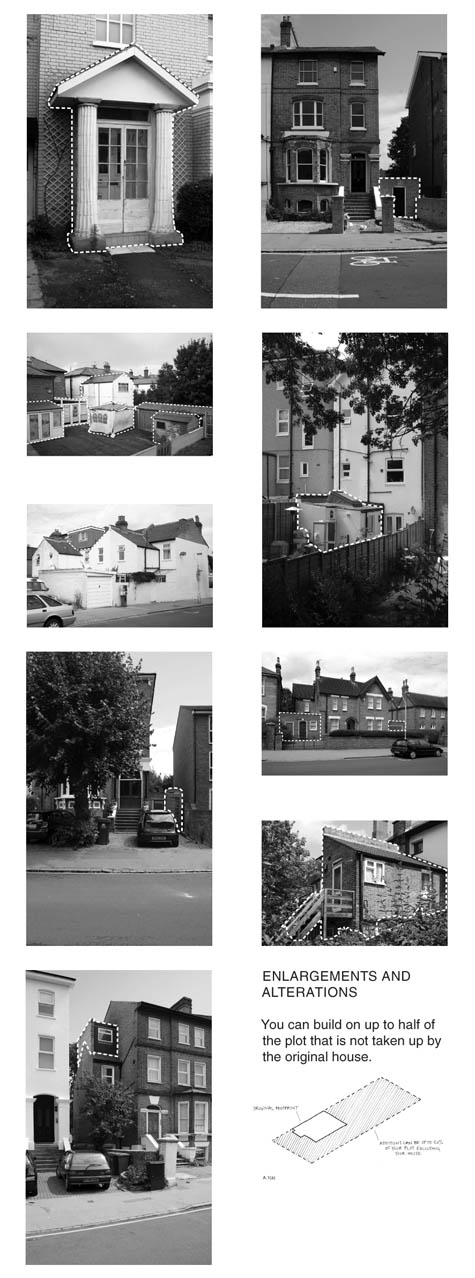

[Image: Courtesy of David Knight and Finn Williams].David Knight and Finn Williams have been investigating what they call "minor development" in the field of architecture and urban planning for several years now, and their discoveries are absolutely fascinating. Last year they published a book called SUB-PLAN: A Guide to Permitted Development, exploring the world of building extensions, temporary structures, outdoor spaces, and other minor acts of home construction that fly beneath the radar of official town planning.

"How far does planning control what we build? And what can we build without planning?" the authors ask. "SUB-PLAN explores the legal possibilities of building outside the limits of legislation."

- The UK planning system has been swamped by minor applications for household extensions and outbuildings that cause a backlog of bureaucracy and dominate the limited resources of local planning authorities. On 1 October 2008 the government introduced changes to the General Permitted Development Order 2 to reduce the number of minor applications by expanding the definition of what can be built without planning permission.

[Images: Courtesy of David Knight and Finn Williams].

[Images: Courtesy of David Knight and Finn Williams].Knight and Williams will be participating in a public conversation next week in London, sponsored by the Architecture Foundation; called Permitted Development: The Planning Permission We Already Have, it will be an example of what we might call legislative forensics, looking into the law books—and the urban planning guidelines—to see what architectural possibilities already exist in the present day for residents to explore.

In that previous sentence, I almost wrote "for residents and homeowners to explore"—but I wonder if you really need to be a homeowner to take advantage of these unpublicized zones of building permission? Is simply being a citizen enough, or must you own property to participate in the realm of minor architecture? Or is there even an unacknowledged world of building practices legally open to construction by non-citizens—by people who, legally speaking, reside nowhere?

In the intersection between architecture and permission, what spaces are possible and who has the right to realize them? What are the possibilities for architectural insurrection—or, at the very least, aesthetic experimentation?

[Image: An awesome glimpse of "the permission we already have," courtesy of SUB-PLAN by David Knight and Finn Williams; view larger].

[Image: An awesome glimpse of "the permission we already have," courtesy of SUB-PLAN by David Knight and Finn Williams; view larger].In Sweden, for instance, there is a type of small garden shed known as the friggebod, named after Birgit Friggebo, Sweden's former housing minister. "The term is a wordplay based on the common term bod: (tool) shed; shack," Wiktionary explains. "The friggebod reform implied that anyone could build a shed of maximum 10 square meters on their premises without obtaining a construction permit from the municipality. In Sweden, the reform became a widely popular symbol of liberalization. From the onset of 2008, the area was increased to 15 square meters."

These autonomous planning zones, so to speak, open up architectural production to non-architects in a possibly quite radical way. So how do we take advantage of them?

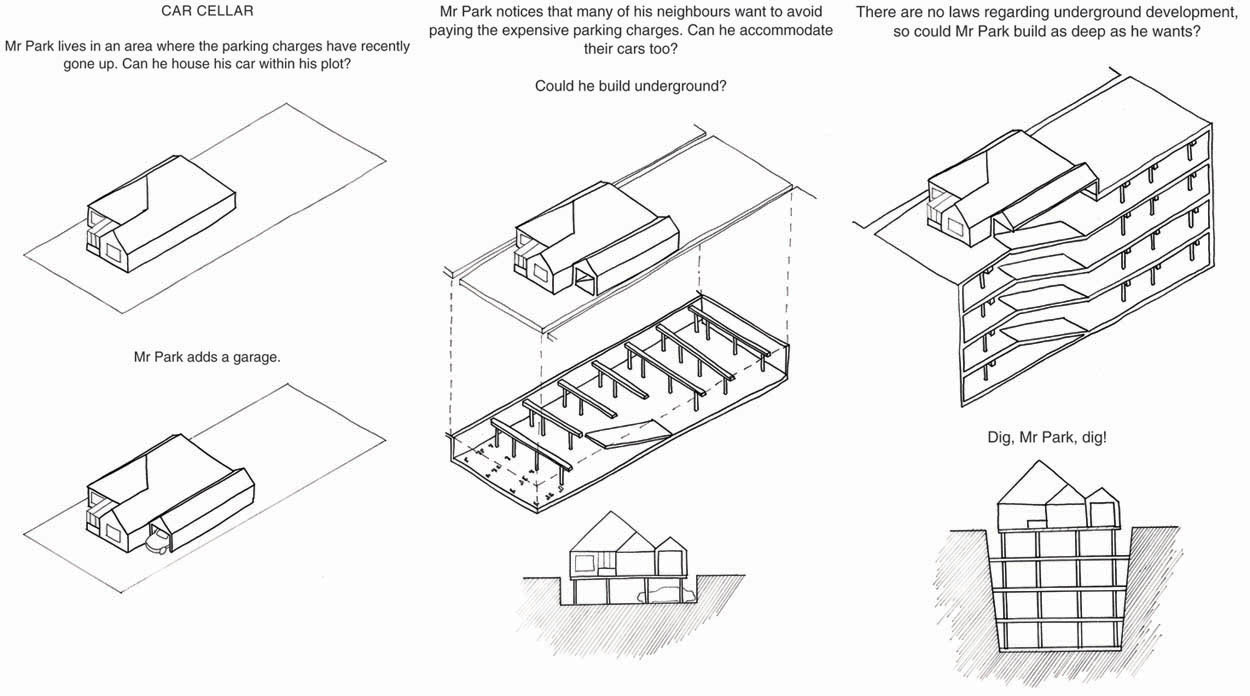

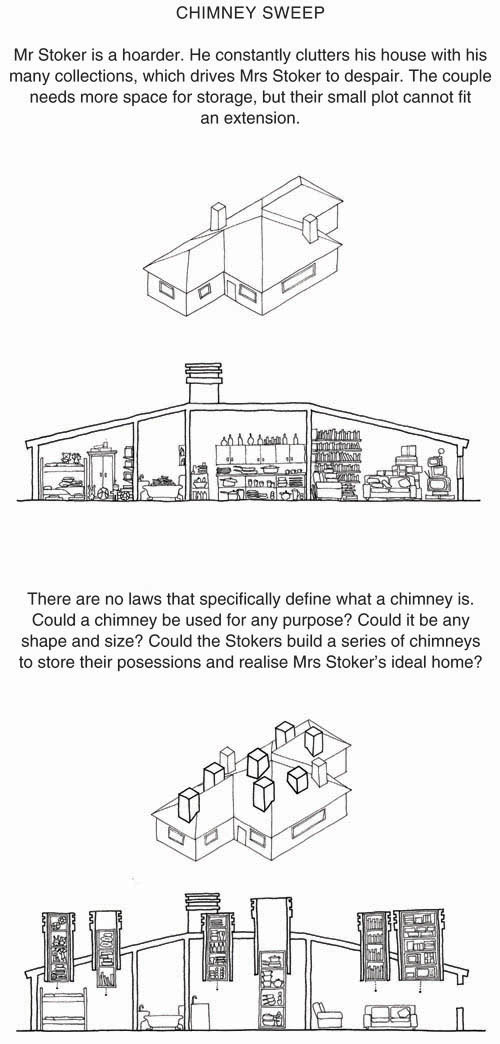

[Images: Another mind-bending example of "the permission we already have," courtesy of SUB-PLAN by David Knight and Finn Williams].

[Images: Another mind-bending example of "the permission we already have," courtesy of SUB-PLAN by David Knight and Finn Williams].Next week's event in London bills itself as follows:

- Though apparently at the humble end of the planning system, recent changes to Permitted Development rights are a treasure trove of architectural potential. The new breed of lean-tos, loft conversions, sheds and summerhouses they allow could have far-reaching and surprising consequences for UK towns and countryside. Finn Williams and David Knight will present recent projects which explore and exploit Permitted Development rules.

What future DIY architectures have yet to arise around us—and when will we set about constructing them?

Comments are moderated.

If it's not spam, it will appear here shortly!

I saw Finn speak today for the Ok. Talk. event hosted at Hel Yes! pop-up Finnish restaurant for London Design Week – super interesting guy, there are two more sessions that I highly recommend to anyone in the city this week.

Stewart Brand's "How Buildings Learn"

is somewhat tangential to this issue of building expansion and spaces derived from user needs beyond the intended planning for such places.

Check it out

http://video.google.com/videoplay?docid=8639555925486210852#

Interesting approach.

It reminds me of the work of Santiago Cirugeda. He points out at similar direction, but he goes go beyond observation. Anonymous practices such as alterations and enlargements are the inspiration and basis for his large catalog of "open code" urban recipes. He encourages citizens to take advantage of legal undefined or ambiguous situations using his urban recipes -which include legal stuff as well as technical details. It's not just speculative work. There are lot of groups making use of them...

www.recetasurbanas.net

There was a post like this a while ago right? It included a plan to build an enormous home theatre addition onto a home? Anybody remember what/where that is?

Jack, if you make it out to see the talk this coming week, let me know; I'd love to hear how it goes.

Timothy, I think you might mean this older post?

Scarlet, I'm a fan of Cirugeda's work, as well, and posted about him a few years ago. Great stuff.

This reminds me of Roger Sherman's book L.A. Under the Influence. He examines how individual parcels are influenced by zoning and other "negotiations between stakeholders." Through some diverse case studies he basically elevates responses to these factors over formal architecture with a capital A. The book also makes a good alternative guide to LA, like Pet Architecture did for Tokyo.

Sadly the authors of the original book need to carry out a tour of duty in a council's Development Control unit- the underground car park would not be permitted development for example, as the main land use would have changed from a single dwellinghouse and would therefore need planning permission for a change of use...

We live in a minefield of planning permissions - dodging them and looking for loopholes is a professional hazard. Unfortunately they are no guarantee of architectural quality under any circumstances - look at the endless housing developments that blot the landscape, the seriously unfortunate amateur add-ons dotted into the urban fabric. Zonings are not even curing crime or transport problems. Need to go back to what we need planning for.......

As a Brazilian, informal architecture is kind of usual for me, so this type of rationale seems very interesting. No wonder our favelas are such a thrill for architects from first world countries...

Timothy, I also thought I already saw that before, but it wasnt in here. It was in Strange Harvest, another great blog, and the link to the post is http://www.strangeharvest.com/2009/12/sub-plan.php

As a small-time landlord, I'd definitely want to consult with a tenant before letting her do some of these things. However, I would not be intrinsically opposed to the idea, and I'd be happy if that were to remain an issue between myself and the tenant, rather than myself and all the different City departments which might get involved.

Post a Comment