|

|

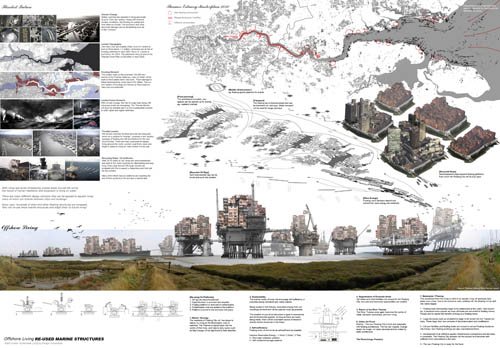

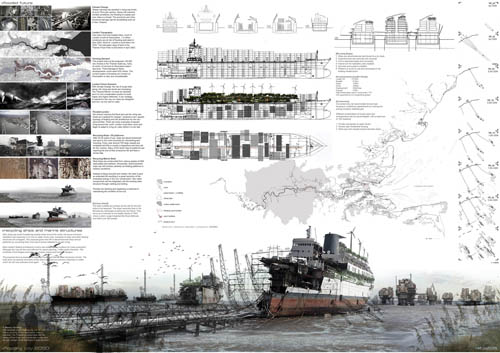

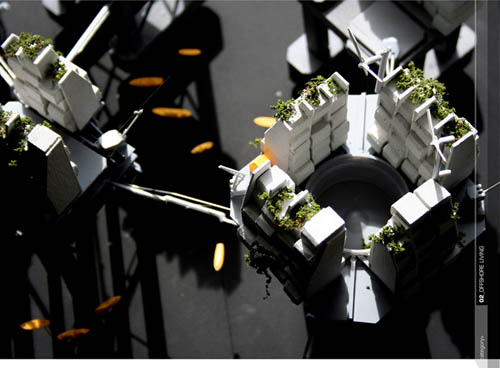

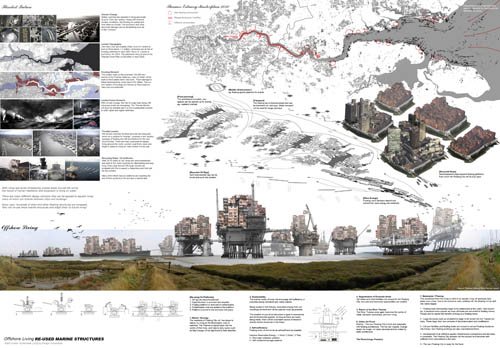

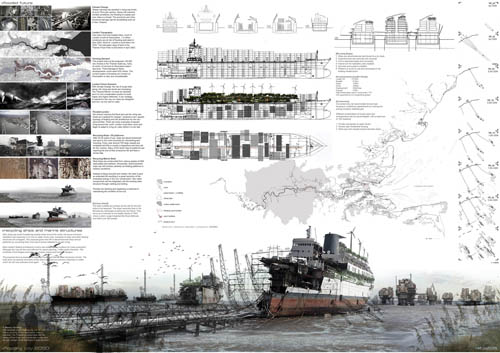

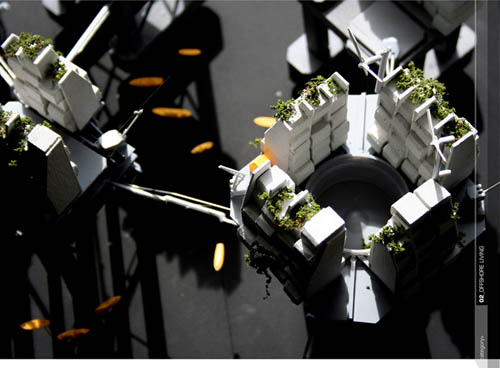

[Image: From "Floating City 2030: Thames Estuary Aquatic Urbanism" by Anthony Lau]. [Image: From "Floating City 2030: Thames Estuary Aquatic Urbanism" by Anthony Lau].Continuing with a look at some noteworthy student projects—which kicked off this week with thesis work by Taylor Medlin—we now look at a proposal by Anthony Lau, submitted back in 2008 at the Bartlett School of Architecture in London. For that project, Lau designed a "floating city" for the Thames Estuary, ca. 2030 A.D. This "Thames Estuary Aquatic Urbanism," as Lau refers to it, "gives new life to decommissioned ships and oil platforms by converting them into hybrid homes adapted for aquatic living." While the idea of offshore architecture has been relatively depleted of its novelty over the last few years, the presentation and imaginative extent of Lau's idea is of sufficiently high quality to deserve wider exposure and a longer look.   [Images: From "Floating City 2030" by Anthony Lau]. [Images: From "Floating City 2030" by Anthony Lau]."Most modern floating architecture involves new-build modular systems for mass production," Lau writes. "Although this may be the most efficient for space planning, it often lacks character." His alternative: The multitude of hull shapes and sizes can inspire unique and inventive design. The proposal aims to express the beautiful forms and internal steel structures of hulls. The hulls serve as nautical reminders of the ship’s past and our previous closeness to water, which we will now embrace once again. The level of detail in Lau's resulting models is astonishing; bridged superblocks of partially rebuilt oil platforms rise from the wetlands, amidst floating gardens and forest barges, like scenes from a maritime-industrial Avalon. You can see larger versions of these images (some of which have been cropped down and recombined to fit the vertical nature of this post, which means that you will see different groupings at this link) here.       [Images: Models from "Floating City 2030" by Anthony Lau]. [Images: Models from "Floating City 2030" by Anthony Lau].As Lau writes: "By utilising the flooded landscape, a floating city of offshore communities, mobile infrastructure and aquatic transport will allow the city to reconfigure through fluid urban planning. Wave, tidal and wind energy will be ideal for this offshore city and the inhabitants will live alongside the natural cycles of nature and the rhythms of the river and tides." He adds that "this strategy for creating a self sufficient floating city by reusing ships and marine structures can also be applied to island nations such as the Maldives. Over 80% of its 1,200 islands are around 1 m above sea level. With sea levels rising around 0.9 cm a year, the Maldives could become uninhabitable within 100 years. Its 360,000 citizens would be forced to adapt and they could become the first floating nation."  [Image: From "Floating City 2030" by Anthony Lau]. [Image: From "Floating City 2030" by Anthony Lau].If Lau's work piques your interest, you might also want to take a look at a report released last year by the Institution of Civil Engineers and the Building Futures group, called " Facing Up To Rising Sea Levels: Retreat? Defend? Attack?" Looking to a 100 year horizon of climate change predictions, we will address how the urban, built environment needs to react now. Conservative estimates predict sea-levels to continue ro rise as the oceans warm and the ice caps melt. Coupled with isostatic rebound (the South sinking relative to the North) the effects grow ever more dramatic for large centers of population on the coast. Predicted weather patterns show increased rainfall intesity, leading to sever problems of surface water flooding in built up areas. The ensuing paper explores the architectural implications of three different hydrological strategies: retreating from the coast, defending what we've built there, and attacking the incoming waters with aggressive engineering. Interestingly, meanwhile, one of Lau's initiatives since graduating from the Bartlett is to form a company focusing on urban bicycle infrastructure, specifically the Cyclehoop, "an award-winning design that converts existing street furniture into secure bicycle parking." It's also quite colorful. But perhaps a Boathoop is in the works for residents of his future Floating City... For substantially larger project images, click here. (Follow Lau's Cyclehoop project on Twitter: @cyclehoop).

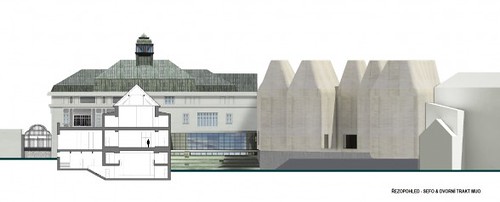

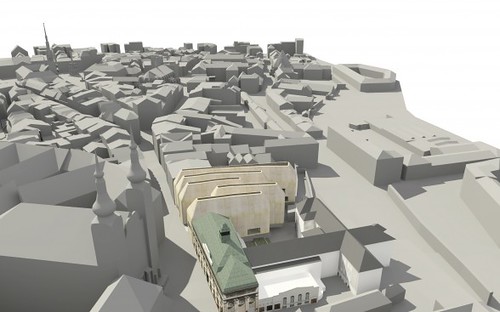

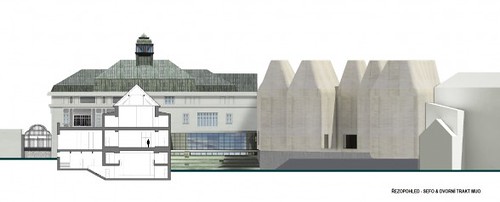

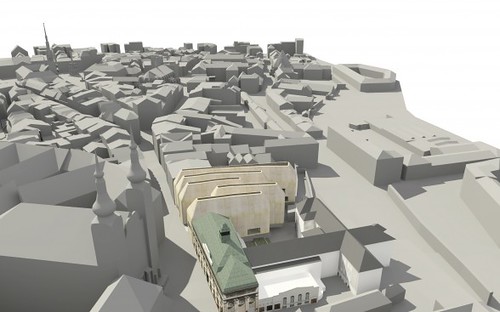

[Image: Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti]. [Image: Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti].I'm a fan of this strangely megalithic museum and cultural center made from a series of concrete shells, colored white with crushed marble, proposed for the Czech city of Olomouc. According to the designers, Šépka Architekti, the project "attempts to draw inspiration from both... a small scale of mediaeval subdivision of land on the one hand and the large scale of palaces, ecclesiastical and military buildings of the Předhradí beginning here on the other."  [Image: Sketch of the Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti, looking vaguely like an inverted, institutional-scale variation on Neil Denari's Useful and Agreeable House]. [Image: Sketch of the Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti, looking vaguely like an inverted, institutional-scale variation on Neil Denari's Useful and Agreeable House].The museum is divided into five apparently separate but linked buildings; this is due to "the necessary separation of the individual functions of the exhibition halls, library, entry hall or bookshop and refreshments," a "necessary separation" that also generates a convenient spatial identity for the overall project. One of the coolest things about the design, though, is what Šépka Architekti call their "house in a house" idea, inspired by access to indirect sunlight: "Even in the cases when an upper floor is inserted in an individual building, daylight is ensured on the lower floor through placement of a smaller structure. We thus approach the topic of a ‘house in a house’, which ensures favourable conditions for the the display of exhibits on the walls while providing light from above on both floors." You can see the formal implications of this in the below image, where a massive, seemingly hovering trapezoid acts both as another, elevated room for gallery use and as a massive, light-filtering device for the skylights further above.  [Image: Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti]. [Image: Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti].It's a mass that casts shadows inside the building. Provided the exterior concrete ages well, the museum's fivefold street presence—briefly stepping back at one point to form a public plaza—is actually pretty stunning. It manages to allude to design languages as diverse as Neo-Brutalism, the Romanesque, a kind of Tatooine Moderne, and computer harddrive casings (although I'm reminded of Owen Hatherley's recent quip about "a modernised classicism, monumental yet free in details, that usually gets subsumed under the meaningless retrospective coinage 'art deco'"—here, we might say, "modern geometries, imposing in size, built from concrete, and thus subsumed under the meaningless retrospective coinage 'Neo-Brutalism'").     [Image: Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti]. [Image: Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti].The results are quite beautiful in profile, even when simply rising up behind the walls of neighboring buildings. In any case, the interior volumes also lend themselves well to defining an overall spatial experience, even while departing from one another just enough to keep each bay or gallery distinct.    [Image: Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti]. [Image: Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti].As mentioned earlier, that interior is a mix of art galleries, a library, a bookshop/cafe, performance spaces, and, oddly enough, as if Photoshopped in simply to prove a point, a basketball court. Note that the stadium seating visible in many of these images has been mounted on rails for ease of rearrangement.      [Image: Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti]. [Image: Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti].In plan, it's interesting to remember that the separate units of the building here were generated from what Šépka Architekti referred to as the "small scale of mediaeval subdivision of land." In other words, the buildings take their formal cue—at least abstractly—from ancient real estate divisions on the ground in Olomouc, not from some overzealous application of the architects' own stylized form of site analysis.    [Image: Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti]. [Image: Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti].The complete building, seen in slices:    [Image: Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti]. [Image: Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti].Further, the "small scale of mediaeval subdivision of land" that I've mentioned three times now also means that what could very easily be an imposing, alien monolith made from smooth white concrete, stuck irresponsibly in the center of the city, actually manages to be appropriate in scale.   [Image: Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti]. [Image: Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti].The building hasn't been constructed, of course, and we have no real idea how the concrete will age; but I was struck by the images from the instant I saw them, flipping through a back issue of a10 yesterday afternoon. Check out more images courtesy of Šépka Architekti.

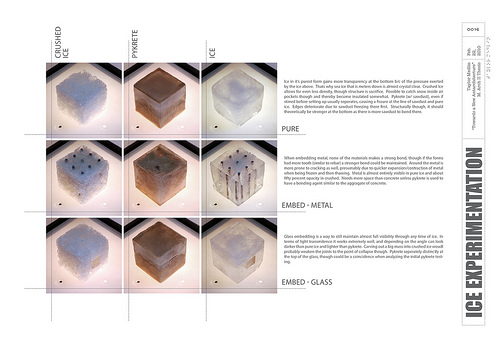

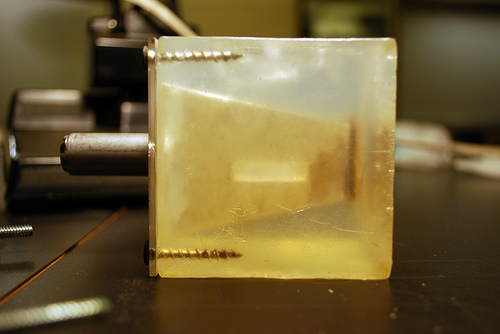

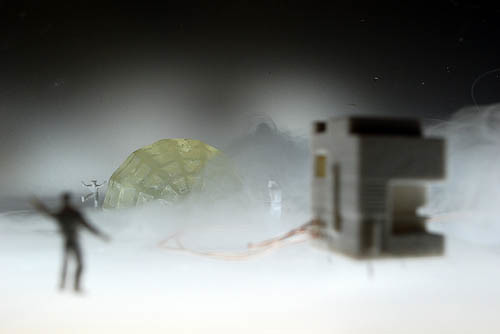

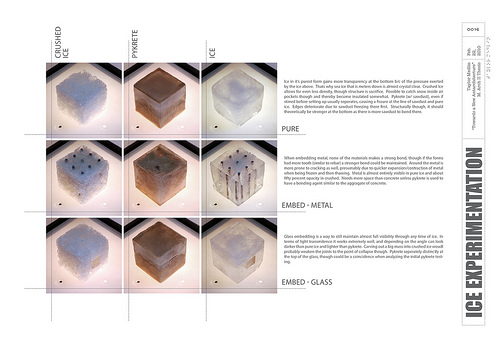

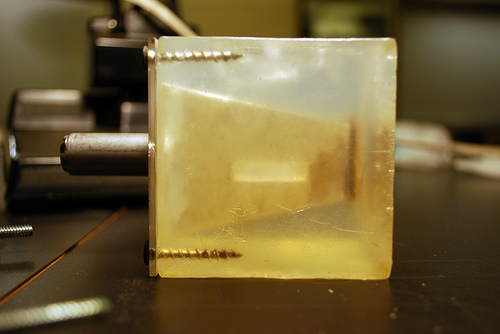

[Image: From "Towards a New Antarchitecture," a thesis project by Taylor Medlin]. [Image: From "Towards a New Antarchitecture," a thesis project by Taylor Medlin].For a stunningly realized thesis project submitted last month at the University of California, Berkeley, Taylor Medlin focused on what he called " Towards a New Antarchitecture." Presented through a combination of miniature wax models and sculpted ice, the project aimed to show how new, more sustainable construction techniques could be developed for the continent of Antarctica.   [Images: From "Towards a New Antarchitecture," a thesis project by Taylor Medlin]. [Images: From "Towards a New Antarchitecture," a thesis project by Taylor Medlin].The only slightly tongue-in-cheek project involved everything from Pykrete— sawdust-reinforced ice once proposed as a genuine alternative to steel in constructing warships—to semi-metalized igloos and ice curtain walls threaded with cylinders of glass. Medlin even created sample ice blocks in a university freezer in order to test a number of these emerging material possibilities. He called this "Ice Experimentation."  [Images: From "Towards a New Antarchitecture," a thesis project by Taylor Medlin]. [Images: From "Towards a New Antarchitecture," a thesis project by Taylor Medlin].The overall project statement read as follows: Antarctica, the most recently explored large land mass in the world, is also currently one of the most unsustainable place on the earth when viewed through the lens of construction techniques. There are over sixty research stations from thirty different countries already built on the continent, all of which are completely constructed out of materials foreign to Antarctica, necessitating huge logistical resources to set up and maintain life there. Though some stations have begun to experiment with energy collection techniques, most remain completely dependent on diesel generators consuming fossil fuels brought from the mainland.

Is it possible to develop construction techniques that take into consideration the materials already present in Antarctica as building blocks for design? And furthermore, what are the possibilities for energy production and conservation that have not yet been explored?

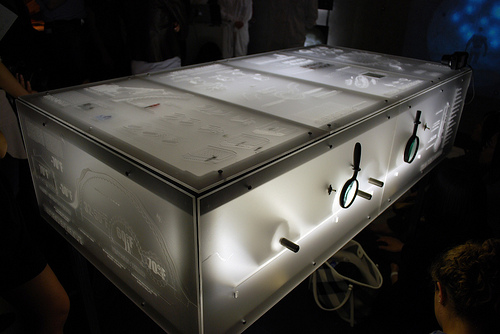

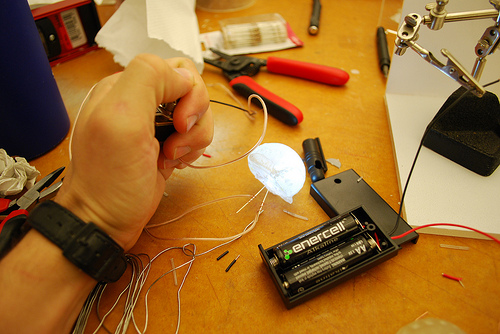

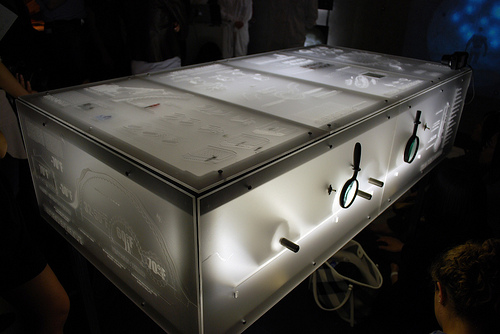

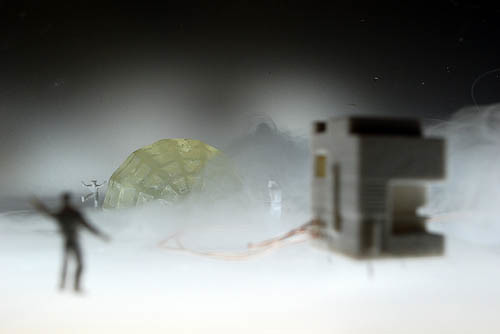

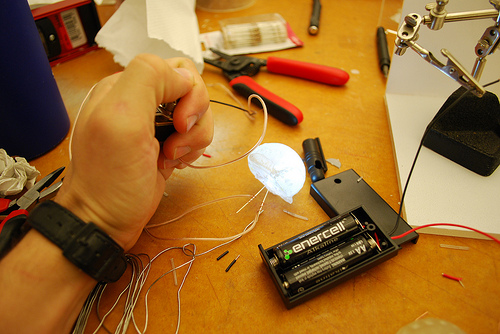

Through the design of a methodology of construction relating to ongoing research stations in Antarctica, I wish to show the plausibility and environmental advantages of designing research stations through the utilization of ice as a principal construction material. Buildings made of ice as a sustainable alternative to projects like Halley VI is a compelling—if perhaps not altogether realistic—idea. Strengthening the ice they'd be made from, using a diverse series of additives—not unlike the " cake mix" mentioned in an earlier post—not only makes it more interesting but materially testable.  [Image: From "Towards a New Antarchitecture," a thesis project by Taylor Medlin]. [Image: From "Towards a New Antarchitecture," a thesis project by Taylor Medlin].Medlin's execution of the final project cabinet is jaw-dropping. Wax models, fisheye lenses, frozen ice maquettes, human figurines, and laser-etched descriptive text, all often lit from within, result in one of the most beautiful student presentations I've seen in a long time. Here are some photos, taken by Medlin, starting off with the miniature wax rooms into which his lenses were embedded—reverse-periscopes looking down into a frozen world:     [Images: From "Towards a New Antarchitecture," a thesis project by Taylor Medlin]. [Images: From "Towards a New Antarchitecture," a thesis project by Taylor Medlin].As objects, these are extraordinary; the design potential for portable lensed microcosms is something well worth exploring in other projects elsewhere. But Medlin offered other ways of seeing into his final project. I think this is genius: in realizing that the fisheye lens approach would not work for everything he'd built, Medlin simply attached magnifying glasses to the exterior of the cabinet. You could thus look through them into a world, one expanding before your very eyes, stocked with people living infra-glacially in an imaginary Antarctic metropolis.    [Images: From "Towards a New Antarchitecture," a thesis project by Taylor Medlin]. [Images: From "Towards a New Antarchitecture," a thesis project by Taylor Medlin].How cool is that! Here are some of the interior sights those lenses allowed:       [Images: From "Towards a New Antarchitecture," a thesis project by Taylor Medlin]. [Images: From "Towards a New Antarchitecture," a thesis project by Taylor Medlin].Finally, the ice structures inside of which Medlin's Antarctic researchers—or future sovereign residents—might live ranged from cuboid huts to geodesic ice domes:   [Images: From "Towards a New Antarchitecture," a thesis project by Taylor Medlin]. [Images: From "Towards a New Antarchitecture," a thesis project by Taylor Medlin].One or two of the resulting scenes are positively mythic, going back to the Nietzschean opening image of this post.  [Image: From "Towards a New Antarchitecture," a thesis project by Taylor Medlin]. [Image: From "Towards a New Antarchitecture," a thesis project by Taylor Medlin].Medlin's behind-the-scenes process documentation is also worth a look; we see him experimenting with battery-powered light sources, hot glue guns, freezer racks, and more. Again, here are some images showing the final display cabinet being assembled.       [Images: From "Towards a New Antarchitecture," a thesis project by Taylor Medlin]. [Images: From "Towards a New Antarchitecture," a thesis project by Taylor Medlin].Now ready for public—and advisor—consumption, Medlin's half-frozen, half-wax, optically activated demonstration cabinet of Antarctic wonders stood deservedly proud amidst its surroundings.  [Image: From "Towards a New Antarchitecture," a thesis project by Taylor Medlin]. [Image: From "Towards a New Antarchitecture," a thesis project by Taylor Medlin].It's worth clicking through the project Flickr page to see many more angles on the work, as well as several whole pages' worth of preparatory images, including templates for the descriptive text that was laser-etched onto the outside of the cabinet. However, it is also worth taking a spin through Medlin's sketchbook. Extensively detailed in 149 separate scanned pages, it is a treat in its own right. From cave dwellings in both Italy and Turkey to Macchu Picchu, Australian Aboriginal stilt houses, and a bizarre glimpse of tree-borne " baby graves," those sketches collectively form a pretty awesome record of Medlin's recent globetrotting adventures (all of which were funded by a John K. Branner Fellowship, which Medlin's fellow student Nick Sowers, often mentioned here, also deservedly received). (In the archives: the Antarctic-themed Manual of Architectural Possibilities #1).

|

|

[Image: From "Floating City 2030: Thames Estuary Aquatic Urbanism" by Anthony Lau].

[Image: From "Floating City 2030: Thames Estuary Aquatic Urbanism" by Anthony Lau].

[Images: From "Floating City 2030" by Anthony Lau].

[Images: From "Floating City 2030" by Anthony Lau].

[Images: Models from "Floating City 2030" by Anthony Lau].

[Images: Models from "Floating City 2030" by Anthony Lau]. [Image: From "Floating City 2030" by Anthony Lau].

[Image: From "Floating City 2030" by Anthony Lau].

[Image:

[Image:  [Image: Sketch of the

[Image: Sketch of the  [Image:

[Image:

[Image:

[Image:

[Image:

[Image:

[Image:

[Image:

[Image:

[Image:

[Image:

[Image:

[Image:

[Image:  [Image: From "

[Image: From "

[Images: From "

[Images: From " [Images: From "

[Images: From " [Image: From "

[Image: From "

[Images: From "

[Images: From "

[Images: From "

[Images: From "

[Images: From "

[Images: From "

[Images: From "

[Images: From " [Image: From "

[Image: From "

[Images: From "

[Images: From " [Image: From "

[Image: From "