Tar Creek Supergrid

For his thesis project at the University of Toronto, Clint Langevin, in collaboration with Amy Norris, proposed "repurposing abandoned mines as renewable energy infrastructure in the U.S."

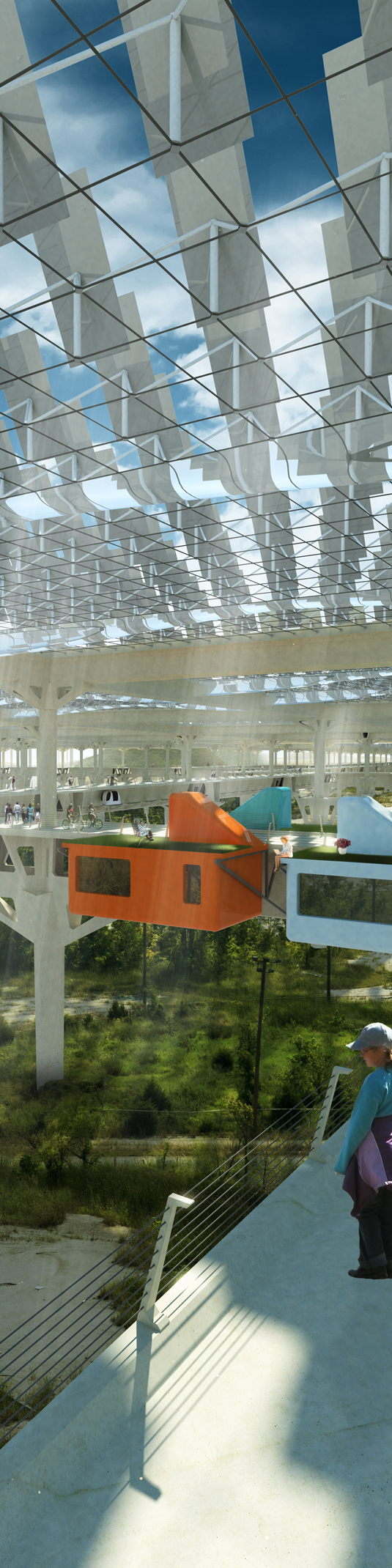

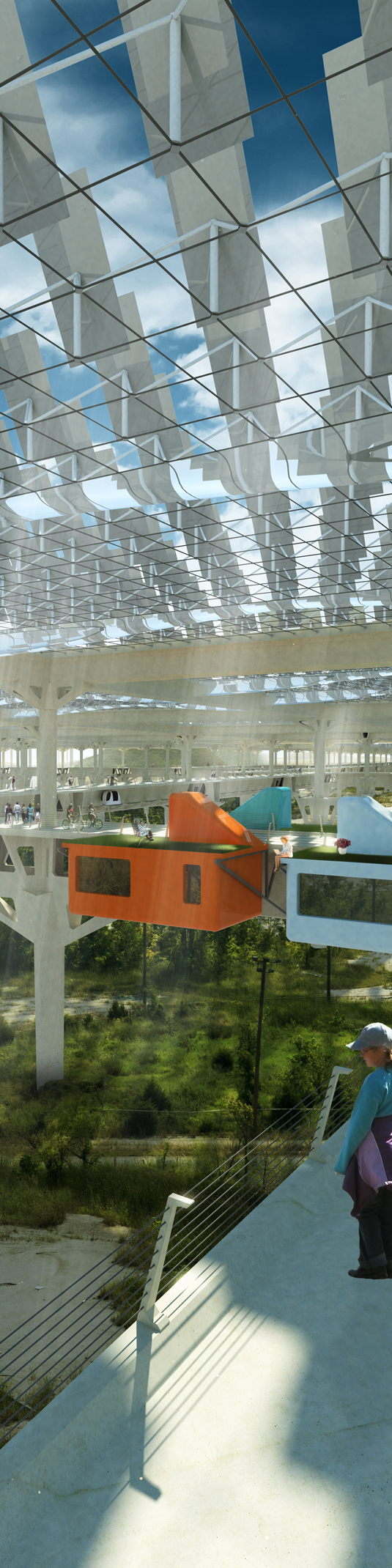

[Image: Inside the Picher, Oklahoma, supergrid, by Clint Langevin and Amy Norris].

[Image: Inside the Picher, Oklahoma, supergrid, by Clint Langevin and Amy Norris].

The specific site for their project is the Tar Creek Lead and Zinc Mine in Picher, Oklahoma, which long-term BLDGBLOG readers might remember as the town at risk from cave-ins. As the Washington Post reported in 2007, "Trucks traveling along the highway are diverted around Picher for fear that the hollowed-out mines under the town would cause the streets to collapse under the weight of big rigs." The unlucky town was then gutted by a tornado in 2008.

Langevin's and Norris's work highlights the area's surreal, almost Cappadocian landscape: "Dozens of waste rock piles, some up to 13-storeys high," they write, "and contaminated ground and surface water are the legacy of mining operations in the area, which produced a significant portion of the lead used in the World Wars."

[Images: Photos of waste rock piles in Picher; (top) Jason Stair, (bottom) Moonlight Cocktail Photography. Photos via the architects].

[Images: Photos of waste rock piles in Picher; (top) Jason Stair, (bottom) Moonlight Cocktail Photography. Photos via the architects].

The architects specifically propose "a structure that raises the solar energy infrastructure off the ground [and] creates the opportunity to host other activities on the site, as well as to remediate the polluted ground and waterways. The concrete structure, pre-fabricated using waste rock material from the site, is assembled in a modular fashion from a kit of parts that accommodates a variety of programs."

[Image: The "kit of parts"].

[Image: The "kit of parts"].

"Importantly," the architects add, "the hollow structure also acts as a conduit to carry water, energy, waste—all the infrastructure for human habitation—to all inhabited areas of the site."

[Images: A wanderer above the sea of white cubes gazes at the Picher supergrid].

[Images: A wanderer above the sea of white cubes gazes at the Picher supergrid].

But inside this continuous and monumental space frame, whole communities could live—the "infrastructure for dwelling" and "pedestrian and cycling circulation system"—surrounded by a toxic geography for which the grid itself serves as both sublime filter and possible remedy.

[Images: More views inside the supergrid; second image is simply a detail from the first (view larger)].

[Images: More views inside the supergrid; second image is simply a detail from the first (view larger)].

The model for the project is pretty great, and I would love to see it in person: a cavernous grid envelopes the site's artificial topography, wrapping tailings piles and hills of waste rock, whilst treading lightly on ground too thin to hold the weight of architecture.

[Images: The model, by Clint Langevin and Amy Norris].

[Images: The model, by Clint Langevin and Amy Norris].

You can see more—including aerial maps and structural details, such as the placement of solar panels—at Langevin's and Norris's site.

[Image: Inside the Picher, Oklahoma, supergrid, by Clint Langevin and Amy Norris].

[Image: Inside the Picher, Oklahoma, supergrid, by Clint Langevin and Amy Norris].The specific site for their project is the Tar Creek Lead and Zinc Mine in Picher, Oklahoma, which long-term BLDGBLOG readers might remember as the town at risk from cave-ins. As the Washington Post reported in 2007, "Trucks traveling along the highway are diverted around Picher for fear that the hollowed-out mines under the town would cause the streets to collapse under the weight of big rigs." The unlucky town was then gutted by a tornado in 2008.

Langevin's and Norris's work highlights the area's surreal, almost Cappadocian landscape: "Dozens of waste rock piles, some up to 13-storeys high," they write, "and contaminated ground and surface water are the legacy of mining operations in the area, which produced a significant portion of the lead used in the World Wars."

[Images: Photos of waste rock piles in Picher; (top) Jason Stair, (bottom) Moonlight Cocktail Photography. Photos via the architects].

[Images: Photos of waste rock piles in Picher; (top) Jason Stair, (bottom) Moonlight Cocktail Photography. Photos via the architects].The architects specifically propose "a structure that raises the solar energy infrastructure off the ground [and] creates the opportunity to host other activities on the site, as well as to remediate the polluted ground and waterways. The concrete structure, pre-fabricated using waste rock material from the site, is assembled in a modular fashion from a kit of parts that accommodates a variety of programs."

[Image: The "kit of parts"].

[Image: The "kit of parts"]."Importantly," the architects add, "the hollow structure also acts as a conduit to carry water, energy, waste—all the infrastructure for human habitation—to all inhabited areas of the site."

The result is a three-tiered plan: the topmost layer is devoted to solar energy development and production: testing the latest solar technology and producing a surplus of energy for the site and its surroundings. This layer is also the starting point for water management on the site. Rainwater is collected as needed and transported through the structure to one of several treatment plants around the radial plan. The middle layer is the place of dwelling and exploration of the site. As the need for space grows, beams are added to create this inhabited layer: the beams act as a pedestrian and cycling circulation system, but also the infrastructure for dwelling and automated transit. Finally, the ground layer becomes a laboratory for bioremediation of the ground and water systems. Passive treatment of both the waste water from the site and of the acid mine drainage is coupled with a connected system of boardwalks to allow inhabitants and visitors to experience both the industrial inheritance of the site and the renewed hope for its future.It's a bit of a Swiss Army knife—in the sense that it tries to solve everything and have a solution for every possible challenge—with the effect that the architects seem to under-emphasize the titanic supergrid that clearly defines the overall proposal. It's as if the proposal is so large—more landform building than architectural undertaking—that even the architects lose sight of it, focusing instead on individual systems in their description.

[Images: A wanderer above the sea of white cubes gazes at the Picher supergrid].

[Images: A wanderer above the sea of white cubes gazes at the Picher supergrid].But inside this continuous and monumental space frame, whole communities could live—the "infrastructure for dwelling" and "pedestrian and cycling circulation system"—surrounded by a toxic geography for which the grid itself serves as both sublime filter and possible remedy.

[Images: More views inside the supergrid; second image is simply a detail from the first (view larger)].

[Images: More views inside the supergrid; second image is simply a detail from the first (view larger)].The model for the project is pretty great, and I would love to see it in person: a cavernous grid envelopes the site's artificial topography, wrapping tailings piles and hills of waste rock, whilst treading lightly on ground too thin to hold the weight of architecture.

[Images: The model, by Clint Langevin and Amy Norris].

[Images: The model, by Clint Langevin and Amy Norris].You can see more—including aerial maps and structural details, such as the placement of solar panels—at Langevin's and Norris's site.

Comments are moderated.

If it's not spam, it will appear here shortly!

This is amazing! So is this happening or purely hypothetical?

Can we try to be a bit more realistic here? There is NO DOUBT that it's a beautiful project but good aesthetics alone will not get projects like this to be realized. If people believe that pretty renderings and architectural drawings will sell the project to cities and governments, then they're living naively.

It's a sublime and idealistic vision- humans living detached from the earth while cleaning up the toxicity. It's a project that seems to spring from the 1960s- it echoes Archigram's habitable infrastructure, constant's New Babylon, and the Japanese metabolists, who were designing megastructures for a world devastated by nuclear fallout.

I like it actually, its expansiveness seems to suit Oklahoma. Personally, I think there is great value in conjectural architecture- because its not really all conjectural- you take pieces of it with you.

i love how even after all these years of the existence of bldgblog, there are still the tired and typical comments scrutinizing the feasibility of the ideas documented here.

this project is incredible. a little shout out to steven fong, who's listed as one of the advisers.

If this is a proposal, I certainly hope you get the backing to do this project. It's fabulous.

THIS IS THE WAY AMERICA NEEDS TO BE THINKING, RE-PURPOSING, and INVESTING!!

Thanks for your all-encompassing visions and designs.

Even if the idea is feasible, can you imagine how shabby it would look in 20 years? All that expansive white concrete (or whatever), weather-stained, cracked.

Modern architecture tends to look good the day it is built -- and then it steadily declines. All of those "clean lines" and such are quickly marred by nature's lack of concern for anything clean or linear.

And oddly enough, brick and stone masonry often just get better with age. A crack here or there just adds more texture to an already-textured surface. Moss growing on brick is lovely; moss growing on a perfect white rectangle looks unwanted and the rectangle looks abandoned.

Also, imagine this thing after a single tornado. It would be completely destroyed, then abandoned, and then the site would be even *more* polluted. Current solar cell technology is actually fairly dirty to produce, and fairly dirty to dispose. Solar furnaces (parabolic mirror arrays focused on a high-temperature receiving tower) are more efficient and far cleaner.

The oddest thing about this idea is how totally it segregates humanity from earth. The humans are literally above the world, a world which is seen as contaminated, a source of both disgust (due to its condition) and shame (since we fouled it).

Post a Comment