|

|

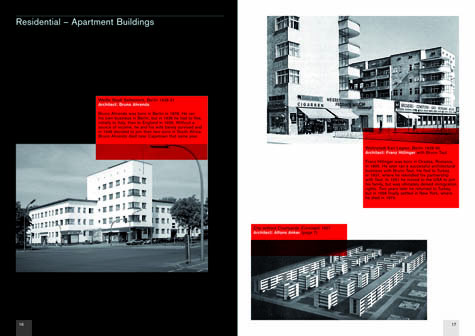

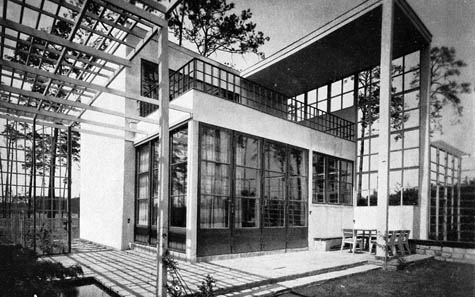

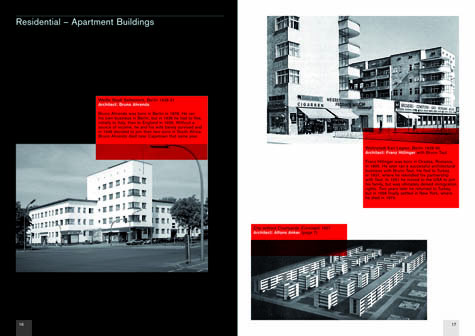

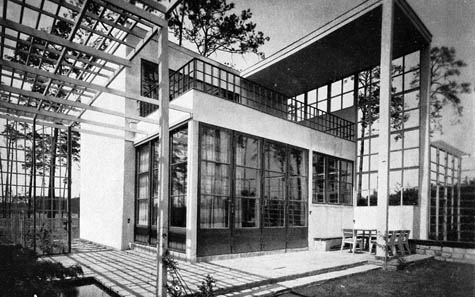

[Image: A spread from Pentagram Papers 37: Forgotten Architects]. [Image: A spread from Pentagram Papers 37: Forgotten Architects].Earlier this month, Pentagram released a pamphlet called Pentagram Papers 37: Forgotten Architects. In the 1920s and early 1930s, German Jewish architects created some of the greatest modern buildings in Germany, mainly in the capital Berlin. A law issued by the newly elected German National Socialist Government in 1933 banned all of them from practicing architecture in Germany. In the years after 1933, many of them managed to emigrate, while many others were deported or killed under Hitler’s regime. Pentagram Papers 37: Forgotten Architects is a survey of 43 of these architects and their groundbreaking work. The work thus presented is based on research performed by Myra Warhaftig, and it is available both online and in a small, beautifully designed booklet. Four of the images you see here are spreads from that publication, courtesy of Pentagram.   [Image: Spreads from Pentagram Papers 37: Forgotten Architects]. [Image: Spreads from Pentagram Papers 37: Forgotten Architects].As Warhaftig wrote in an introduction to the project: On 1 November 1933, a few months after the German National Socialist Government came to power, a decree was issued banning Jewish architects from the Reichskulturkammer für bildende Künste, the state-governed association of fine art to which membership was required to practice architecture. Their academic titles were revoked and they were denied the use of the professional title "architect." Just short of two years later, on 15 September 1935, another law was adopted, further excluding from the association all so-called Half-Jews and those who were married to Jews. In total, nearly 500 architects were affected by the ban and forced to leave Germany. Those who stayed had to go into hiding or were deported to ghettos or concentration camps.  [Image: A spread from Pentagram Papers 37: Forgotten Architects]. [Image: A spread from Pentagram Papers 37: Forgotten Architects].She continues: After long and circuitous routes, I have succeeded in locating relatives of the deceased architects. Scattered across all continents, they were able to offer additional authentic material. These historical documents and biographies, as well as photographs of the architects' buildings, are published for the first time in my book German Jewish Architects Before and After 1933: The Lexicon. Many of the buildings these architects produced were absolutely extraordinary – and, frankly, it seems impossible not to look at these images and judge 20th century Germany in light of the catastrophic stupidities that led to its murderous exile of the creative classes, whether those were physicists, novelists, abstract expressionists, or even architect members of the Bauhaus. Indeed, it's impossible to look at today's European landscape in general and not spot absences, or losses, voids here and there punctuating the 21st century town and city.  [Image: Tietz Department Store in Solingen (1930?), designed by Georg Falck; photo via Archive Dr. Hagspiegel]. [Image: Tietz Department Store in Solingen (1930?), designed by Georg Falck; photo via Archive Dr. Hagspiegel].The images here show some of the buildings that Myra Warhaftig's research, performed up until her death only three weeks ago, uncovered. Many more shots are available on Pentagram's project website.       [Images: Showcase House, Werkbundsiedlung Breslow, by Moritz Hadda (1929); Terraced Houses, Berlin, by Alfons Anker (1929-30); Arnold Zweig Residence (1929-30), Eisner Residence (1927), and Schulze Residence (1928-29), all in Berlin and all magnificent designs by architect Harry Rosenthal; and a police station in Berlin by Richard Scheibner (1930-31)]. [Images: Showcase House, Werkbundsiedlung Breslow, by Moritz Hadda (1929); Terraced Houses, Berlin, by Alfons Anker (1929-30); Arnold Zweig Residence (1929-30), Eisner Residence (1927), and Schulze Residence (1928-29), all in Berlin and all magnificent designs by architect Harry Rosenthal; and a police station in Berlin by Richard Scheibner (1930-31)].Referring to the architects whose work is featured in the above seven photographs: In 1933, Georg Falck fled with his family to the Netherlands: "In Amsterdam they survived in hiding until the end of the war. Falck died in a New York Hospital in May 1947, just six weeks after he and his family had emigrated to the USA." Alfons Anker's business partners joined the Nazi party in 1933; six years later, he "managed to flee to Sweden, but never succeeded in re-establishing his career as an architect. Anker died in Stockholm in 1958." Harry Rosenthal, architect of three houses featured above, "was born in Posen (today Poznan, Poland) in 1892. He lived and worked in Berlin where he ran a successful architectural practice. In 1933 he managed to flee to Palestine, but suffered from the subtropical climate. In 1938 he emigrated to England, where despite numerous attempts, he did not manage to re-establish his architectural career. He died in London in 1966." In 1941, Moritz Hadda "was deported to an unknown location." Richard Scheibner's "fate is unknown." (Thanks to Michael Bierut and Kurt Koepfle at Pentagram for sending the booklet and spreads).

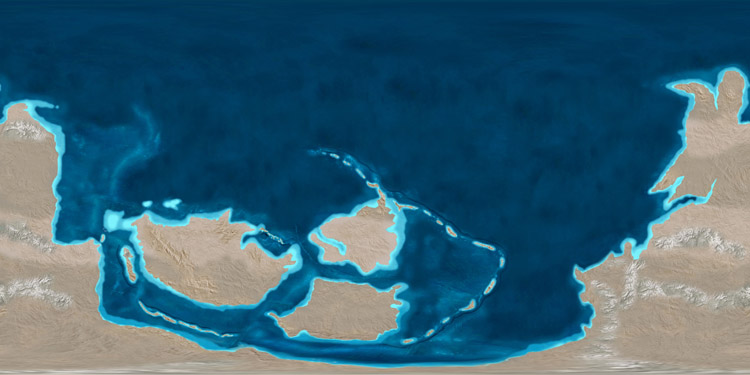

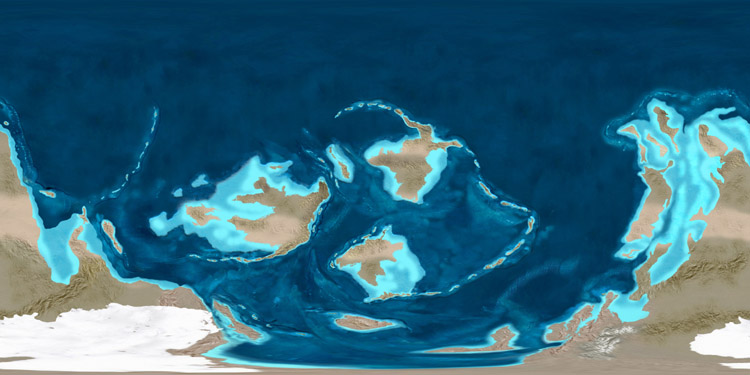

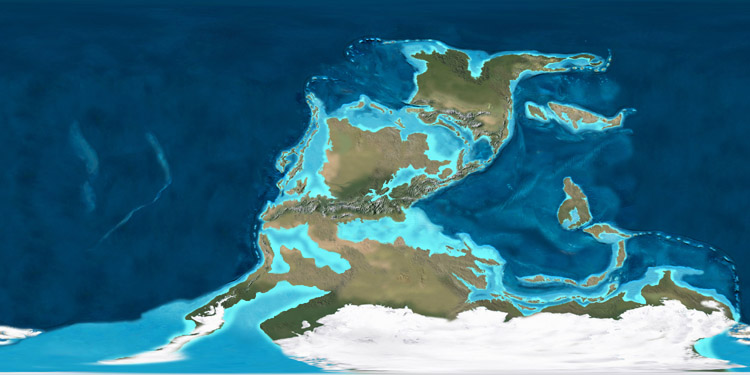

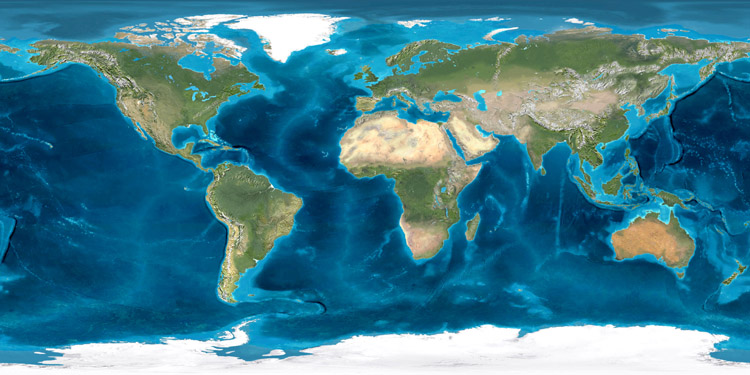

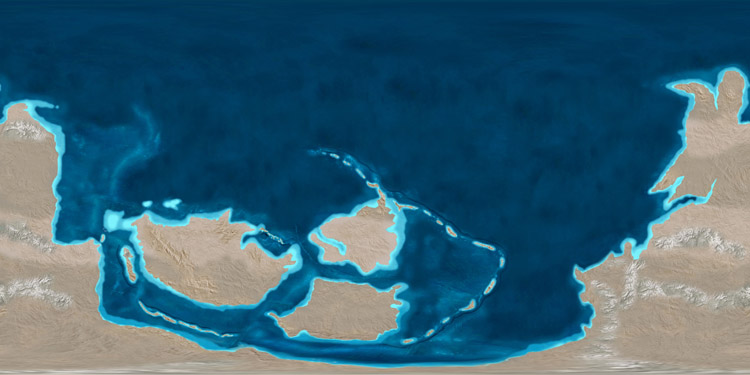

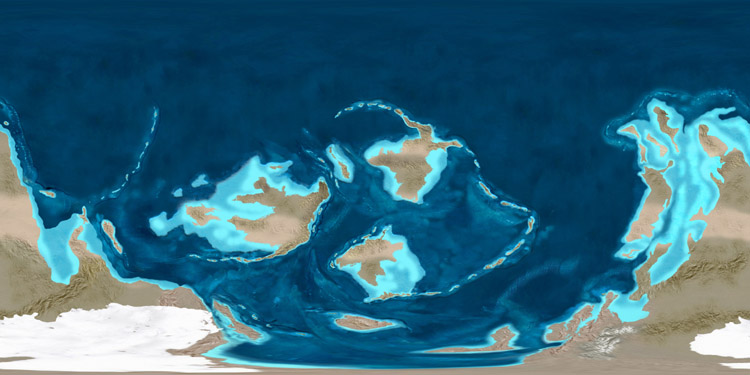

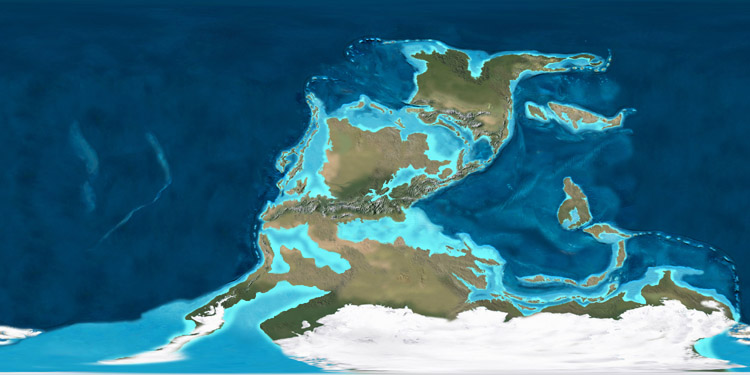

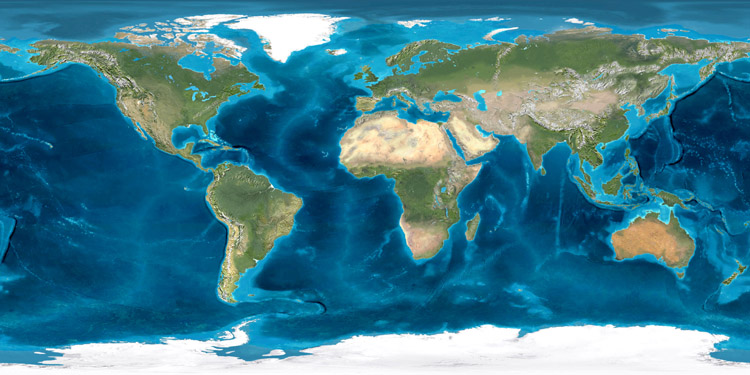

I've been looking at Ron Blakey's maps of the tectonic evolution of the earth's surface again, and I just absolutely love these things.  [Image: The earth 600 million years ago, in the late Precambrian Era; mapped by Ron Blakey]. [Image: The earth 600 million years ago, in the late Precambrian Era; mapped by Ron Blakey].In fact, I think Blakey should be given some sort of science prize for putting these together; these help to visualize broad historical processes in a way that is visually clear, conceptually unforgettable, and imaginatively provocative, to say the least. And these images, posted here, are only one series among many that Blakey's assembled – and these aren't even all the images in that series. For that, you'll have to visit Blakey's site. So what you're looking at here is continental drift over a period of 600 million years, beginning with the Late Precambrian Era, above, through to the present day, in the penultimate image, below.     [Images: The tectonic paleo-history of the earth; mapped by Ron Blakey]. [Images: The tectonic paleo-history of the earth; mapped by Ron Blakey].That sequence of four images, above, gives us the earth as a kind of northward spray of island arcs and micro-continents, small landmasses moving toward evolutionary isolation. What must it have been like, I wonder, if we could somehow have taken a sailboat in and around those tropical seas, weaving through vast semicircular island chains, finding reefs and bays, lagoons and inlets, anchoring offshore and camping on the beaches of an absolutely dark earth, electricity-less and lit from above by stars – with all the constellations different back then, as even the galaxy itself is still unfolding, full of alien patterns in the sky.    [Images: The tectonic paleo-history of the earth; in the last two images, you can see recognizable landmasses just beginning to form. Maps by Ron Blakey]. [Images: The tectonic paleo-history of the earth; in the last two images, you can see recognizable landmasses just beginning to form. Maps by Ron Blakey].Something else that fascinates me – and you can see this in the next three images – is the fact that, until relatively recently, Europe was actually an Indonesia-like archipelago, distributed throughout warm northern latitude waters. One of the residues of this geography is a massive fossilized reef that I wrote about here on BLDGBLOG almost exactly two years ago. Referring to that reef in an article from 1991, New Scientist wrote that, "if we could travel 160 million years back in time," we would find a reef "that occupied most of what is now Europe." At first sight this reef and its communities have striking similarities to the Great Barrier Reef. But this ancient reef structure is unique; its main architects were not corals, but multicellular marine sponges, many of which have no match today. And this reef was even bigger than the Great Barrier Reef. Its fossil remains stretch about 2900 kilometeres from southern Spain to eastern Romania, making it one of the largest living structures ever to have existed on Earth. If you look at the following three images, then, you'll see how and where "one of the largest living structures ever to have existed on Earth" was able to form.    [Images: The earth from roughly 150 million years ago to 50 million years ago; mapped by Ron Blakey]. [Images: The earth from roughly 150 million years ago to 50 million years ago; mapped by Ron Blakey].Then, of course, we hit the present day – pictured below. Suddenly this arrangement looks rather impermanent.  [Image: The earth in its present continental configuration; mapped by Ron Blakey]. [Image: The earth in its present continental configuration; mapped by Ron Blakey]. It's extraordinary to realize, then, that this sequence of images represents only 600 million years of geological time – because the earth has something like seven and a half billion years to go before solar extinction. And though plate tectonics may actually cease someday, let's say that a healthy billion and a half more years of continental rearrangement are still in store for this world; what fantastic inland seas and archipelagos might yet be waiting to form? Extrapolating from these very images into the future, as our planet continues to delink and spread, maneuvering its surfaces around in endless reconfigurations, is a time-consuming but worthwhile thought experiment; if we could get Blakey to speculate upon the tectonic future of the earth, for instance, that would indeed be something to see. Of course, this is something that New Scientist actually wrote about this past winter, suggesting three possible evolutionary scenarios for where these nomadic fragments of our planet's surface might end up: Geologists now suspect that the movements of the Earth's continents are cyclical, and that every 500 to 700 million years they clump together. Unfolding over a period three times as long as it takes our solar system to orbit the centre of the galaxy, this is one of nature's grandest patterns. So what drives this cycle, and what will life be like next time the continents meet? The article then gives us the hypothetical outlines of three possible supercontinents.  [Image: Three possible supercontinents, as mapped by New Scientist: Novopangaea, Amasia, and Pangaea Proxima; view larger]. [Image: Three possible supercontinents, as mapped by New Scientist: Novopangaea, Amasia, and Pangaea Proxima; view larger].As if these things are a matter of preference, let me absurdly point out that I am actually not a big fan of supercontinents; I think they're boring. Luckily, they seem to crack apart based upon their own weight and bulk; in other words, like many Americans, supercontinents are too heavy for their own good. Personally, I like archipelagos and island arcs. In fact, might there be some way to hack the earth's surface and ensure a supercontinent-free planet to come? We could somehow help certain portions of the earth's surface to unzip, forming new island chains, and we could perforate continental shields the world over to assist with their future fragmentation... In any case, what's also interesting about these maps is that, taken as a whole, the last 600 million years appear really to have been a kind of mass northward migration of landmasses, as if the continents were pulled from one pole to the other by temporary, if monumental, spreading and subduction zones. Again, though, these are not all the images in the series; for that, you'll have to check out Ron Blakey's website. And, seriously, someone needs to give this guy a fellowship or an award or something – these maps are just fantastic. [Image: These images are also available in a small Flickr set].

Passing electricity through soil, and into the roots of plants, might stimulate the accelerated production of certain chemicals, New Scientist reports.  "The roots of garden pea plants were exposed to low-level electric current and subsequently produced 13 times more pisatin, an antifungal chemical, than plants that were not exposed to electricity," we read. The specific experiment on which this claim is based involved applying "a 30 to 100 milliamp current to the growth-medium of plants grown hydroponically, or, in the case of barrel medic, to the solution surrounding the cell cultures." So is this the future of gardening? Growing hydroponic plants in an electrically charged, semi-liquid matrix in order to "stimulate" the production of new forms and compounds? You could perhaps plant star anise in vast, swampy test plots surrounded by High Voltage signs, and thus derive new anti-flu drugs from electrically active roots. Or generate new orchids, supersymmetrical and glowing, plugged directly into an electrical earth. The Philadelphia Flower Show will never be the same. Or plug gardens like this into a solar power plant out in the desert somewhere – and a weird new form of exponential photosynthesis is born.

I've got a new post up on io9 this afternoon, and it might be of interest to readers here. That post asks: Can fictional sites and spaces – in particular, things taken from science fiction – be included in online map sets, and what might the implications be? You look up "New York state" on Google Maps, but it includes a new layer of information: the routes and locations traveled by characters in Steven Spielberg's War of the Worlds. Or you go to London only to find that the dashboard navigation system in your car includes all the major locations from The Day of the Triffids. In other words, if we can map science fiction into our cities, using online tools, how might that affect our experience of urban space? These and other questions all pop up in Google Maps of Sci-Fi. Let me know what you think.

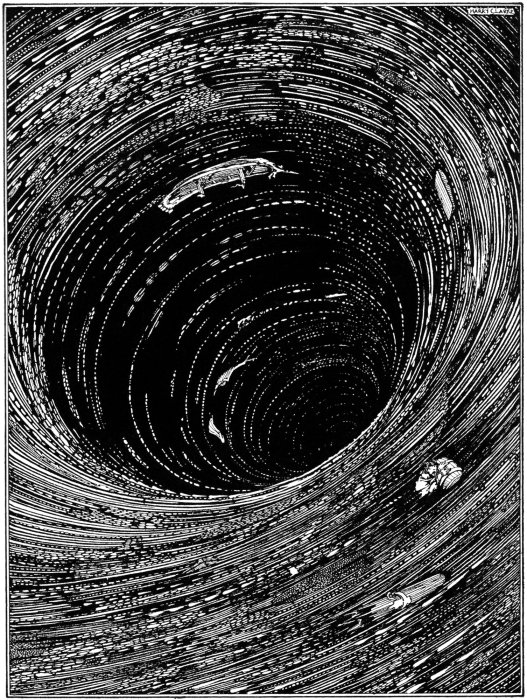

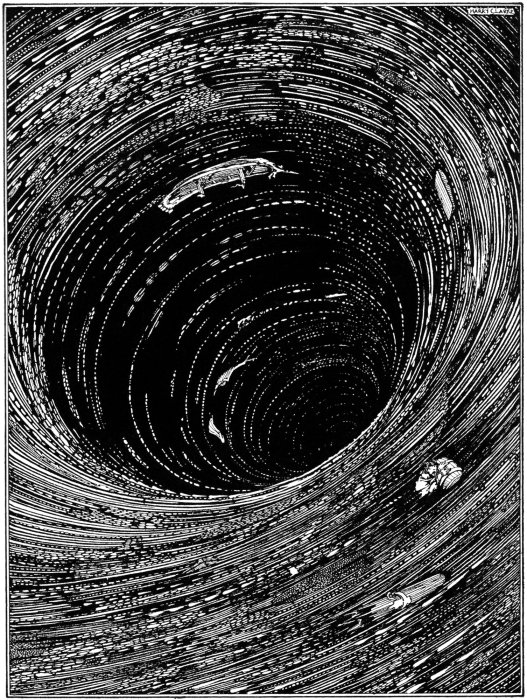

It was reported a few days ago that a " giant ocean eddy" has formed off the coast of Australia, and it now "shadows Sydney." It's nearly 300km wide. The oceanic vortex "completes a full revolution every 10 days and the sea level at its centre is reduced by nearly 1m, which is how researchers can tell where the eddy is.” It is now "an ocean feature approaching the size of Tasmania."  [Image: An illustration for Edgar Allan Poe's Descent into the Maelstrom, by Harry Clarke]. [Image: An illustration for Edgar Allan Poe's Descent into the Maelstrom, by Harry Clarke].Unfortunately, the eddy is "dissipating" – but it might yet turn into something else. After all, the eddy has an aqueous antecedent: "A mysterious, huge and dense mass of cold water is milling off the coast of Sydney," we were told by a reporter for Cosmos, back in March 2007. The eddy is "baffling researchers and delighting fishermen" – and sowing the seeds of what has become today's hyper-eddy. And last year's eddy was already huge. As Giles Foden wrote in the Guardian, it "carrie[d] more water than 250 Amazon rivers." Inspired, Foden cites Edgar Allan Poe: The edge of the whirl was represented by a broad belt of gleaming spray; but no particle of this slipped into the mouth of the terrific funnel, whose interior, as far as the eye could fathom it, was a smooth, shining, and jet-black wall of water, inclined to the horizon at an angle of some forty-five degrees, speeding dizzily round and round with a swaying and sweltering motion, and sending forth to the winds an appalling voice, half shriek, half roar... "While they cannot be described as a freak of nature," Foden continues, "eddies as large as that discovered off Sydney can play a significant part in unexpected climate events" – and that brings us back yet another year, to 2006, for more news of weird vortices off the coast of Australia. Moving to the other side of the continent, we find a " death trap" at sea: A massive ocean vortex discovered off the West Australian coast is acting as a "death trap" by sucking in huge amounts of fish larvae and could affect the surrounding climate. A scientist who visited the site "said the climate above the vortex was noticeably different. 'It feels like you're in the tropics,' she said. 'It's warm, soft, moist air, with flying fish, it's a very different environment.'" And I love this: "We were in a 70-metre boat and you could immediately feel the shift in the ship's tract, so you can certainly tell that there's something unusual going on out there," she said. Spontaneous misdirection at sea. So could that "something unusual" be repeated elsewhere? And though I mean naturally, perhaps it could even be done artificially: a vast stirring operation at sea, brought to you by Boeing... In fact, I'm tempted to pitch a science fiction film: a huge eddy forms off the coast of Manhattan, stirring up deep currents of sludge and dumped trash from the 1970s. The waters turn thick. Syringes and other forms of medical waste re-appear. The beaches of Long Island are closed. And then strange blood infections hit the local fishermen. And then the fishermen begin to change... as the eddy drifts closer to shore. Or, for that matter, set the film in San Francisco. Cloverfield 2. (Thanks to Alexis Madrigal for the tip!)

[Image: From a great series of photos called Coasts of Britain (2006), by Jacob Carter]. [Image: From a great series of photos called Coasts of Britain (2006), by Jacob Carter].There's a particular book I've read eight times now – and, as of yesterday's lunch break downtown, I'm reading it again. This sounds unbelievably boring, even to me, but I can't help it; this particular book, a novel, which I'll call ***, in both an evasion and a clue, just haunts me. In fact, I'm sure I'll read it a tenth time someday – but, then, some people have seen Titanic twenty-five times, and other people have never even read one novel, let alone one novel every few years, so it is what it is, because it worked out that way. In any case, I first read this book way back in middle school – and there is a point to all this, so bear with me. I then re-read it, borrowing it from a friend out of sheer desperation for anything published in English, living abroad for the first time about ten years ago – and I was genuinely stunned to find that the book said literally the exact opposite of what I'd remembered it saying. It was like being confronted with a distorting mirror, or an old set of photographs – a very visceral, even embarrassing, way of realizing how much a person might change. Given time, how different are your sources of significance. For good or for bad. On top of that, of course, I found I really liked the book. So I read it again a few years later – and, because I was traveling again with nothing else to read, a few days after finishing it I started back on page one. And so on. If anything, it's like a form of happenstance that became a behavior. Now it's March 2008 and I bought a new copy of the same book yesterday on a whim from a bookstore near my office – and, being a person who underlines things, I found myself last night underlining totally different passages, little sentences here and there that had never struck me as even remotely interesting before, or meaningful, or really anything more than neutrally descriptive. It occurred to me, then, that everyone should pick a book – a novel, a work of theory, poetry, biography, whatever – and re-read it every few years, but they should do this for the rest of their lives. It becomes an indirect kind of literary self-measurement: understanding where you are in life based upon how you react to a certain text. So it's not some weird sign of obsession, then, or awkward proof that you've been caught in a nostalgic rut. It's more like running a marathon every few years: the same distance covered, huffing and puffing at a different age. How do you measure up? And how does it measure up to you?  [Image: Via Old UK Photos]. [Image: Via Old UK Photos].Of course, I realized, that's why some people read the Bible over and over again, or even the Koran: it's less a form of worship, or a sign of spiritual neediness, than a kind of literary way of marking your height in the same old doorsill, seeing how high you now stand. You are, so to speak, being measured. But why should we only do these sorts of thing by reading books? Why not measure ourselves, and our movement in life, against a piece of architecture?  [Image: Piranesi]. [Image: Piranesi].The idea here is that you'd pick a building somewhere in the world, something outside your normal sphere of experience, and you'd visit it every few years. You were there as a kid – or as a teenager, or as a young man or woman – and you were terrified by the unlit marble stairways... but that view from the third floor is just astonishing. The Musée d'Orsay, or the Metropolitan Museum of Art, or Westminster Abbey, or the Pantheon, or the Pyramids. The Temple of Heaven. Angkor Wat. The docks of Rotterdam. You show up; you've set the whole day aside, like going to see a very long film. Or running a marathon. And you proceed to ride the elevators and escalators. You sit down at certain windows. You stand there in the corner just looking around. You go into rooms you once knew. Maybe it's an old hotel or hostel you've stayed in; maybe it's an entire town, or a hospital you basically lived in for three weeks because someone in your family was sick. Maybe it's your best friend's house. It doesn't matter. You drink some coffee, or you cross your arms, or you walk back and forth for an hour, paying attention to things you never would have noticed had you not come back. You take notes, and you compare them to last time. Maybe it's a train station in New York. Maybe it's an airport. Maybe it's an old garden outside the city that no one visits. Every time you're there, you're different. As a kid you liked it because it made you feel lost; now you hate it because it makes you claustrophobic. Come back in ten years, and that landscape of routes and perimeters is exactly what you need again: it's expensive and confusing and not even well-designed – but it's much-needed proof that you can always disappear. You're there for hours.  [Image: Via Old UK Photos]. [Image: Via Old UK Photos].Or maybe it's a hiking path out in the woods somewhere, or the Appalachian Trail, or a ruined cathedral. A whole neighborhood or district of the city. You're standing inside the Colosseum in Rome, and you can build whole new chains of significance and reason now, plugging in variables, making room for things beneath the outward armor of age – and it's all because you came back, to see or feel how things might be different for you in reaction to something you're not. It's like taking an exam every few years – only the exam is a piece of architecture, and the questions change every time you answer them.  [Image: Piranesi]. [Image: Piranesi].In any case, is there an architecture of self-measurement? Is there a way to time ourselves across whole lifetimes through buildings? Is that what religious pilgrimages have always been about? And is that what architecture critics should be forced to do? Or is this nothing but distracting nostalgia? Could you somehow test yourself against the built environment, regularly, over the course of a lifetime, and do so deliberately, with purpose, the way people once wrote philosophy or read poems or traveled the world? You enter the building. You notice something new. It clicks.  [Image: Temple at Angkor, photographed by flydime]. [Image: Temple at Angkor, photographed by flydime].Is the experience of architecture ever an accurate form of self-assessment – assuming there's a real self to assess? Or is all of this just useless melancholy, looking back through a haze of sentimental desperation for anything with significance – and attempting, unsuccessfully, to alight upon the gates of architecture? Or might the regular re-experience of certain buildings be a kind of emotional or intellectual marathon for the people who come back to experience them? They measure themselves through the experience of built space.

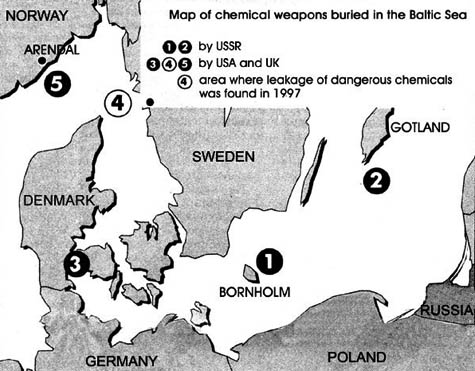

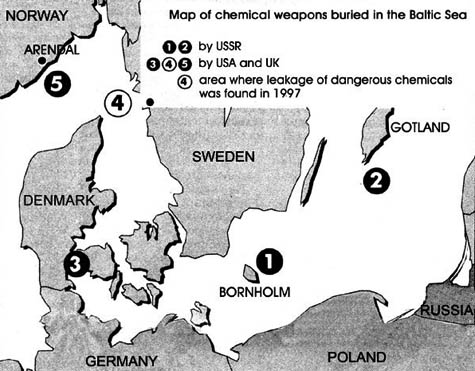

[Image: Chemical weapons dumping sites in the Baltic Sea; via]. [Image: Chemical weapons dumping sites in the Baltic Sea; via]."The last thing you might expect to encounter exploring the ocean floor is a chemical weapon," New Scientist writes. "But it seems hundreds of thousands of tonnes of them have been dumped into the sea, and no one knows exactly where the weapons are. Now, scientists are calling for weapons sites to be mapped for safety's sake." Between 1946 and 1972, the US and other countries pitched 300,000 tonnes of chemical weapons over the sides of ships or scuttled them along with useless vessels...

But the military have lost track of most of the weapons because of haphazard record keeping combined with imprecise navigation. Even the exact chemicals were not always noted, though there are records of shells, rockets and barrels containing sulphur mustard and nerve agents such as sarin. While this particular article, in New Scientist, focuses on the U.S. military – and, more specifically, the chemical weapons it dumped south of Hawaii – there are, of course, other, global examples of such behavior. This post's opening image, for instance, documents sites at which "chemical weapons were dumped in the Baltic Sea after the Second World War." Of course, it's not always chemical weapons that get scuttled at sea.  [Image: Via the USGS]. [Image: Via the USGS].According to the United States Geological Survey: Between 1946 and 1970, approximately 47,800 large barrels and other containers of radioactive waste were dumped in the ocean west of San Francisco. The containers were to be dumped at three designated sites, but they litter a sea floor area of at least 1,400 km2 known as the Farallon Island Radioactive Waste Dump.

The exact location of the containers and the potential hazard the containers pose to the environment are unknown. This is all the more reason, then, that these sites need to be mapped. Somewhat ominously, at least from my perspective, the Farallon Islands are a short sail west by northwest from the neighborhood in which I'm writing this; on clear days you can even see them while hiking on the coast of Marin County.  [Image: The Farallon Islands, via NOAA]. [Image: The Farallon Islands, via NOAA].The radioactive history of the Farallons is actually quite extraordinary. In 2001, for instance, SF Weekly suggested that "the Navy dumped far more nuclear waste than it's ever acknowledged in a major commercial fishery just 30 miles west of San Francisco." The Weekly then relates the story of a man named Jim Gessleman. "Part of his regular job," we read, in reference to Gessleman's time in the Navy between 1955 and 1959, "was to escort a barge carrying radioactive waste under the Golden Gate Bridge and out into the Gulf of the Farallones. There, the bottom of the barge would open to release containers of radioactive waste into the sea." Horrifically: "Another part of Gessleman's job was to shoot holes in the barrels that didn't immediately sink, so that they would. He says he did his job – shooting about 10 to 20 barrels once or twice each week – which means that many of the Navy's radioactive waste containers were breached before they ever reached the bottom of the sea, and became part of what is known as the Farallon Islands Nuclear Waste Site." So what exactly is down there? The short answer is that no one seems to know. But, among many other things, including the entire U.S.S. Independence, we can be sure that "significant amounts of the nuclear bomb component plutonium, which has a half-life of 24,000 years, and similarly long-lived 'mixed fission' products," are all floating around down there in the darkness. And perhaps it's all now billowing in a red tide near you... In fact, later researchers, studying this undersea dumping ground within sight of the mansions and bank towers of San Francisco, "found plutonium, cesium, and americium – an isotope that emits about three times as much radioactivity as radium – in the fish [caught on-site]. In particular, americium and one kind of plutonium were found at levels higher than has been reported at any other site in the world" (emphasis in original). As it now stands, however, "approximately 85 percent of the nation's largest undersea nuclear waste dump has never been observed or tested."  [Image: Via the USGS]. [Image: Via the USGS].Returning to the question of chemical weapons at sea, a report by Environmental Science & Technology explains that an area roughly the size of Delaware has been used off the coast of California as a dumping ground for non-nuclear chemical weaponry. Yet the U.S. military hasn't limited itself to its own sovereign shores. From the Daily Press in 2005: The Army now admits that it secretly dumped at least 64 million pounds of chemical warfare agents, as well as more than 400,000 mustard gas-filled bombs and rockets, off the United States – and much more than that off other countries, a Daily Press investigation has found.

The Army can't say where all the dumpsites are. There might be more.

The Army is missing years of records on where it secretly dumped surplus chemical weapons from the close of World War II until 1970, when the practice was halted. It hasn't reviewed any records of post-World War I at-sea chemical weapons dumping but knows the practice was commonplace at the time.

More than 30 U.S.-created chemical weapon dumpsites are scattered off other countries, the newly released Army report indicated. In any case, where will all this stuff be in a thousand years, a hundred years, fifty years – or fifty centuries? Will apocalyptic tides wash upon the coasts of the world in the year 3088, bringing radiation and nervous paralysis to millions? Will these lost and often unacknowledged military toxins even interact with, and help catalyze, new gene lines at the bottom of the sea – and, in 500,000 years, some distant mutant cousinry, like a real-life Godzilla, might emerge from the frothy waves?  And, whether or not anything of the sort ever happens, is there really any way to produce an accurate map of these and other dumping sites? Things shift; barrels move; information is lost; sand can cover everything. And even that assumes you'd get the funding you need to buy equipment – from side-scanning radar to air tanks and wet suits. Still: what future cartography might yet detect and publish these places – so that we can avoid them, or clean them, or entomb them there beneath the sea in glaciers of black concrete? Of course, even those glacial tombs will someday tectonically re-emerge, or crack, or seismically collide with other landmasses, spilling open – and, at least in the case of radiation, creatures tens of thousands of years from now – far longer than the recorded history of human civilization – might yet find a mysterious sickness, drifting invisibly through the water, from a source that's lost to time. [Belated thanks to Steve S. for originally mentioning the Farallon Islands story].

[Image: From The Museum of Nature by Ilkka Halso]. [Image: From The Museum of Nature by Ilkka Halso].Anyone in the Philadelphia area looking to hear about climate change, ruined cities, tectonic warfare, James Bond, the literal end of the earth, and a bit of Hollywood-style archaeology, consider stopping by Meyerson Hall at the University of Pennsylvania (located here), at 3:30pm today – the first Friday of Spring – to hear BLDGBLOG talk about these and other subjects. This will be a combination of my Bartlett, SCI-Arc, and AIA-Baltimore lectures, focusing specifically on long-term landscape processes – aka landscape futures. The above image, for instance, from The Museum of Nature by Finnish photographer Ilkka Halso, will be making an appearance. So come check it out! It's free and open to the public, and should last roughly an hour, with maybe some coffee and drinks afterward for a bit. Meanwhile, I will be reporting soon about the Baltimore talk – which was a blast, and for which I owe a gigantic thanks both to the AIA-Baltimore and to Preservation Maryland – including a recap of the actual lecture.

[Image: Photo courtesy of the U.S. Navy, via the New York Times]. [Image: Photo courtesy of the U.S. Navy, via the New York Times].At one point in college I worked at the school's student radio station, where everyone would write mini-reviews onto white stickers placed on the front covers of CDs – but there was one album I remember that sounded, someone wrote, "like the dream of a submarine's machinist passing under the polar ice cap," a description which has stuck with me to this day. So I was interested to see an article this morning in the New York Times about a "brotherhood of submariners" during the Cold War who had their own "doomsday preparations," weaving in and out of the polar ice. In 1970, for instance: In great secrecy, moving as quietly as possible below treacherous ice, the Queenfish, under the command of Captain Alfred S. McLaren, mapped thousands of miles of previously uncharted seabed in search of safe submarine routes. It often had to maneuver between shallow bottoms and ice keels extending down from the surface more than 100 feet, threatening the sub and the crew of 117 men with ruin.

Another danger was that the sub might simply be frozen in place with no way out and no way to call for help as food and other supplies dwindled. Of course, this suggests an image of abandoned submarines embedded in the Arctic ice, becoming architectural – well-machined pieces of landscape, officially unacknowledged and governmentally unclaimed. After this mission, in particular, we read, "the Arctic became a theater of military operations" – and a place to play polar hide and seek.  [Image: Map courtesy of the New York Times, based on information from Unknown Waters by Alfred S. McLaren]. [Image: Map courtesy of the New York Times, based on information from Unknown Waters by Alfred S. McLaren].The navigational challenges presented by ice are apparently quite daunting, on the other hand: "ice dangling from the surface in endless shapes and sizes made the sub's main eyes – sonar beams that bounce sound off the bottom and surrounding objects – work poorly." That is, you'd detect whole ghost geographies out there, made of misdirected pings and echoes, passing through transparent landforms of sound that don't exist. But moving into these sorts of ethereal terrains was all part of the larger strategy of modern statecraft: if the Cold War was anything, it was the exhibition of sovereign intent upon landscapes outside of national borders – whether that's Vietnam, Afghanistan, or the self-transforming mobile echo chambers of ice that drifted in and out of polar darkness, with strange machines whirring by in the waters below.

I've got a new post up on io9 this morning, and it may or may not be of interest to BLDGBLOG readers.  It's about what the world might look like if Hollywood celebrities, hip-hop moguls, international financiers, and so on got addicted to digging tunnels... So they start excavating multi-million dollar show caves beneath their mansions in London, drilling vast catacombs throughout the Hollywood Hills. Robert Downey Jr. Colin Farrell. Ludacris. Even Bob Dole. It's the show caves of the nouveau riche.

[Images: Photos via the BBC and the Washington Post]. [Images: Photos via the BBC and the Washington Post].A story on the BBC that I neglected to blog last week explains how the capital of Chad will soon be encircled by a gigantic trench: "A three-metre [10-foot] deep trench is being dug around Chad's capital, N'Djamena, to force vehicles through one of a few fortified gateways into the dusty city," we read. Additionally, like some strange, new, paranoid version of Easter Island, "tree surgeons [have] cut down centuries-old trees that lined the city's main avenue for fear they could provide cover for attackers." Prepared for war and insurgency, then, the city will strip itself bare. "It's part of our strategy," the Interior Minister claims. These are just "initiatives to prevent attacks from rebels based in the east of the country." It's also interesting to note, though, that, in the absence of enemy air power, basic urban design moves – like trenches and gates – can still be used as an effective tactic of defense during war.  [Image: The "trenches of approach," via Wikipedia; view larger]. [Image: The "trenches of approach," via Wikipedia; view larger].In fact, I'm reminded of Alberto Pérez-Gómez's book, Architecture and the Crisis of Modern Science, in which he writes about the geometric history of urban fortifications – such as those seen on Deputy Dog last month. As Pérez-Gómez writes, referring to military treatises produced in western Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries: "All military problems were described in terms of lines and angles..." War, to put it glibly, was a function of measurement and trigonometry. Bernard Palissy, in particular, a 17th century theoretician and builder of fortified space, discovered that some of the best military geometries were to be found in the bodies of maritime organisms: Palissy believed that existing fortified towns failed because their protecting walls were not really part of the towns' architecture. He tried to find better ideas in the treatises of the old masters, but was sadly disappointed. In desperation, he turned to nature and after traversing woods, mountains, and valleys, he arrived at the sea. It was there that he observed "the miraculous protection of mollusks like oysters and snails." As Pérez-Gómez summarizes this: "The sea snail was clearly the best prototype for a fortified city." What's particularly interesting about this, however, is that Palissy – and other military architects of the time – saw fortified cities as all but divinely ordained; quoting an architect named Jacques Perret de Chambéry, Pérez-Gómez notes that military architecture "could thus represent an order in which 'all nations may praise the Lord' and 'live according to His Holy Laws.'" Military architecture was, to this way of thinking, religious architecture.  [Image: Star fort diagrams, via Wikipedia]. [Image: Star fort diagrams, via Wikipedia].Things even got a bit Da Vinci Code here. For instance, we read that certain military architects "recommended the use of square, pentagonal, or hexagonal fortifications since these figures were symbols of the relation between the human body and the cosmos." Further, dividing space within these fortified cities into four distinct parts meant that the space could correspond "to the four regions of the sky, thus emulating the cosmic order." In fact, Pérez-Gómez notes, a man named Mathias Dögen even included, in a treatise on war and space, "long sections in which he provided detailed instructions on how to conquer cities, taken from the 'Laws' established in the Holy Scriptures." This idea – that military architecture was a way to inscribe "cosmic order" onto the surface of the earth – is almost ridiculously interesting. How does that play out today – in Camp Bondsteel, for instance? But even the briefest suggestion that something as tactical, pragmatic, and strategically rooted in measurement as 17th century European warfare might actually have harbored this mystical underside surely deserves more exploration elsewhere.  [Image: Star fort diagrams, via Wikipedia]. [Image: Star fort diagrams, via Wikipedia].In any case, reading this in the context of today's War on Terror – with its slow encroachment of blast walls and other anti-terror architecture into the very heart of our now fortified cities – I'm led to ask if we might be witnessing the makeshift inscription of a new sort of "cosmic order" into urban space, worldwide. Or, to put it another way: How do well-fortified Western cities in an age of Global Terror give shape to, or represent, much larger, more subtle, and perhaps immaterial details of a religious world view? Might we yet see a religious theorization of 21st century urban space, in which anti-terror architecture plays a central role? Is there an underexplored theological dimension to crash barriers, Bremer walls, and armed checkpoints? That may wildly overstate the case, of course – but I'm reminded of an article in Salon, published way back in 2006, where we read: To appreciate how America has changed since 9/11, walk slowly through any major city. What you'll see dotting the landscape is the physical embodiment of fear. Security installations put up after the attacks continue to block public access and wrangle pedestrian traffic. Outside Manhattan's Port Authority Bus Terminal, garish purple planters menace rush-hour pedestrian traffic. The gigantic planters have abandoned all horticultural ambition, many of them blooming with nothing more than trash and untilled dirt. Further: It's not just the barriers, it's also the buildings. Since 9/11, risk consultants working for police departments, federal agencies and insurance companies have wrested control over many new construction plans. "There's a sense that security experts are acting as the associate architects on every project built today," says Paul Goldberger, the architecture critic of the New Yorker. Consultants tend to encourage architectural bulk at the expense of grace. So the question is: What happens when we put the security-obsessed 21st century city – whether that's N'Djamena, Chad, with its 10-foot deep trench or New York City with its flowerless planters – into the context of Alberto Pérez-Gómez's book on the religious significance of military fortifications? How does that change the discussion?  [Image: A photo by Randy of a fortified road on the way to Rachel's Tomb, Bethlehem – an old city of stone walls overshadowed by a new city of concrete blast walls]. [Image: A photo by Randy of a fortified road on the way to Rachel's Tomb, Bethlehem – an old city of stone walls overshadowed by a new city of concrete blast walls].So if religiously inspired military architects of the 17th century were the "risk consultants" and urban "security experts" of their day, then how might their treatises read if updated for the War on Terror?

With the BLDGBLOG Book still on my plate here, it might be another slow week on the blog – maybe not – but I do want to announce something else before it's too late: and that's that I will be giving an hour-long lecture next week in Baltimore, hosted by the American Institute of Architects.  Specifically, it's this year's Michael F. Trostel Lecture, sponsored by Preservation Maryland. I'll be speaking about everything from the historical preservation of American highway infrastructure north of Baltimore to the curatorial problems associated with underwater archaeological sites in the Mediterranean Sea. There will be stabilized ruins, abandoned prisons, a post-human Detroit, the architectural reuse of war debris, gene banks, epoxy-sealed Utah arches, and the slow fossilization of cities over eons of geological time. There will be liquid silicone, plaster casts of famous statuary, and old Hollywood film sets preserved by the desert sand. You have to pay to get in, unfortunately – it's $15 – but I think it's free for students, and there might be some kind of discount if you are a member of the AIA. It's on Wednesday, March 19, at 6pm. It's in this building, which is located here. So please come out! Keep me on my toes. Look at weird images. Laugh at bad jokes. Somewhat incredibly, meanwhile, the lecture series only includes myself, Gregg Pasquarelli, Teddy Cruz, and Daniel Libeskind.    Finally, the AIA-Baltimore webpage says, incorrectly, that I am the founder and editor of Archinect – but that is Paul Petrunia, who founded Archinect nearly 11 years ago, in the fall of 1997. I am just one editor among more than a dozen there – and I'm not a very active one, at that! Apologies to Paul for the confusion. Hope to see some of you next week in Baltimore! Seriously – it should be fun.

|

|

[Image: A spread from Pentagram Papers 37: Forgotten Architects].

[Image: A spread from Pentagram Papers 37: Forgotten Architects].

[Image: Spreads from Pentagram Papers 37: Forgotten Architects].

[Image: Spreads from Pentagram Papers 37: Forgotten Architects]. [Image: A spread from Pentagram Papers 37: Forgotten Architects].

[Image: A spread from Pentagram Papers 37: Forgotten Architects]. [Image: Tietz Department Store in Solingen (1930?), designed by Georg Falck; photo via Archive Dr. Hagspiegel].

[Image: Tietz Department Store in Solingen (1930?), designed by Georg Falck; photo via Archive Dr. Hagspiegel].

[Images: Showcase House, Werkbundsiedlung Breslow, by Moritz Hadda (1929); Terraced Houses, Berlin, by Alfons Anker (1929-30); Arnold Zweig Residence (1929-30), Eisner Residence (1927), and Schulze Residence (1928-29), all in Berlin and all magnificent designs by architect Harry Rosenthal; and a police station in Berlin by Richard Scheibner (1930-31)].

[Images: Showcase House, Werkbundsiedlung Breslow, by Moritz Hadda (1929); Terraced Houses, Berlin, by Alfons Anker (1929-30); Arnold Zweig Residence (1929-30), Eisner Residence (1927), and Schulze Residence (1928-29), all in Berlin and all magnificent designs by architect Harry Rosenthal; and a police station in Berlin by Richard Scheibner (1930-31)].

[Image: The earth 600 million years ago, in the late Precambrian Era; mapped by

[Image: The earth 600 million years ago, in the late Precambrian Era; mapped by

[Images: The tectonic paleo-history of the earth; mapped by

[Images: The tectonic paleo-history of the earth; mapped by

[Images: The tectonic paleo-history of the earth; in the last two images, you can see recognizable landmasses just beginning to form. Maps by

[Images: The tectonic paleo-history of the earth; in the last two images, you can see recognizable landmasses just beginning to form. Maps by

[Images: The earth from roughly 150 million years ago to 50 million years ago; mapped by

[Images: The earth from roughly 150 million years ago to 50 million years ago; mapped by  [Image: The earth in its present continental configuration; mapped by

[Image: The earth in its present continental configuration; mapped by  [Image: Three possible supercontinents, as mapped by

[Image: Three possible supercontinents, as mapped by  "The roots of garden pea plants were exposed to low-level electric current and subsequently produced 13 times more pisatin, an antifungal chemical, than plants that were not exposed to electricity," we read. The specific experiment on which this claim is based involved applying "a 30 to 100 milliamp current to the growth-medium of plants grown hydroponically, or, in the case of

"The roots of garden pea plants were exposed to low-level electric current and subsequently produced 13 times more pisatin, an antifungal chemical, than plants that were not exposed to electricity," we read. The specific experiment on which this claim is based involved applying "a 30 to 100 milliamp current to the growth-medium of plants grown hydroponically, or, in the case of  I've got a new post up on io9 this afternoon, and it might be of interest to readers here.

I've got a new post up on io9 this afternoon, and it might be of interest to readers here.  [Image: An illustration for Edgar Allan Poe's

[Image: An illustration for Edgar Allan Poe's  [Image: From a great series of photos called

[Image: From a great series of photos called  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: Temple at Angkor, photographed by

[Image: Temple at Angkor, photographed by  [Image: Chemical weapons dumping sites in the Baltic Sea;

[Image: Chemical weapons dumping sites in the Baltic Sea;  [Image: Via the

[Image: Via the  [Image: The Farallon Islands, via

[Image: The Farallon Islands, via  [Image: Via the

[Image: Via the  And, whether or not anything of the sort ever happens, is there really any way to produce an accurate map of these and other dumping sites? Things shift; barrels move; information is lost; sand can cover everything. And even that assumes you'd get the funding you need to buy equipment – from side-scanning radar to air tanks and wet suits.

And, whether or not anything of the sort ever happens, is there really any way to produce an accurate map of these and other dumping sites? Things shift; barrels move; information is lost; sand can cover everything. And even that assumes you'd get the funding you need to buy equipment – from side-scanning radar to air tanks and wet suits.  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: Photo courtesy of the U.S. Navy, via the

[Image: Photo courtesy of the U.S. Navy, via the  [Image: Map courtesy of the

[Image: Map courtesy of the  It's about what the world might look like if Hollywood celebrities, hip-hop moguls, international financiers, and so on got addicted to digging tunnels...

It's about what the world might look like if Hollywood celebrities, hip-hop moguls, international financiers, and so on got addicted to digging tunnels... [Images: Photos via the

[Images: Photos via the  [Image: The "trenches of approach," via

[Image: The "trenches of approach," via  [Image: Star fort diagrams, via

[Image: Star fort diagrams, via  [Image: Star fort diagrams, via

[Image: Star fort diagrams, via  [Image: A photo by

[Image: A photo by  With the BLDGBLOG Book still on my plate here, it might be another slow week on the blog – maybe not – but I do want to announce something else before it's too late: and that's that I will be giving an hour-long lecture next week in Baltimore, hosted by the

With the BLDGBLOG Book still on my plate here, it might be another slow week on the blog – maybe not – but I do want to announce something else before it's too late: and that's that I will be giving an hour-long lecture next week in Baltimore, hosted by the  Specifically, it's this year's Michael F. Trostel Lecture, sponsored by Preservation Maryland.

Specifically, it's this year's Michael F. Trostel Lecture, sponsored by Preservation Maryland.

Finally, the AIA-Baltimore webpage says, incorrectly, that I am the founder and editor of

Finally, the AIA-Baltimore webpage says, incorrectly, that I am the founder and editor of