Urban X-Ray / Ancient Orchard

[Image: A Roman Triumph following the sack of Jerusalem].

[Image: A Roman Triumph following the sack of Jerusalem].Amongst the many books I'm reading here in Rome this month – including Tobias Jones's surprisingly good Dark Heart of Italy, the incredible Anatomy of Fascism by Robert Paxton (J.G. Ballard wrote that he "found Paxton's post-mortem deeply unsettling, with its strong hint that the corpse [of fascism] might sit up at any moment and seize us by the throat" – Exhibit A here might be Andrew Brons's election this week to the European Parliament), and Roger Deakin's Waterlog – I'm making my way through two books by Mary Beard.

Beard, of course, was the subject of a long, two-part interview with BLDGBLOG back in 2007.

What I want to mention here comes from her book The Roman Triumph; it's only a brief quotation, but I like it.

At one point Beard refers to the "theaters and porticoes" built in ancient Rome using wealth taken during Pompey's "eastern campaigns" in Armenia and elsewhere. However, she writes:

- The term "theaters and porticoes" hardly does justice to this vast building complex, which stretched from the present day Piazza Campo del Fiori to the Largo Argentina, covering an area of some 45,000 square meters. A daring – and, for Rome, unprecedented – combination of temple, pleasure park, theater, and museum, it wrote Pompey's name permanently into the Roman cityscape. Even now, though no trace remains visible on the ground, its buried foundations (and particularly the distinct curve of the theater) determine the street plan and housing patterns of the city above; it remains a ghostly template which accounts for the surprising twists and turns of today's back-streets, alleyways, and mansions.

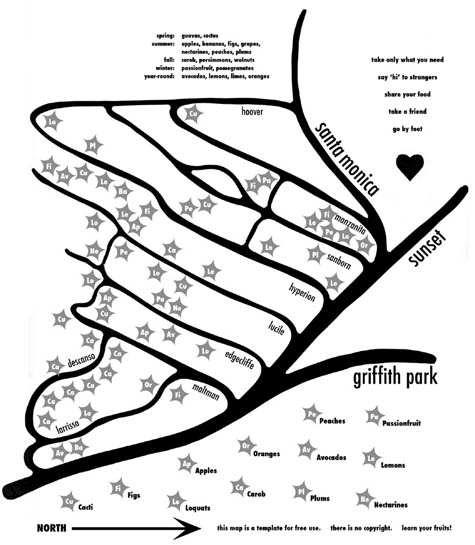

[Image: Fallen Fruit's map of the lost orchards of Silver Lake].

[Image: Fallen Fruit's map of the lost orchards of Silver Lake].During their presentation, the ingenious duo Fallen Fruit mentioned that, when they were mapping fruit trees in today's Los Angeles, they stumbled upon the borders of much older, abandoned fruit orchards.

In other words, what appeared simply to be a random fig tree growing in someone's front yard was, when seen on a map together with other such trees, actually the remnant presence of a now-forgotten farm.

Those trees, to use Beard's term, are the "ghostly template" from an earlier phase of land use.

There is a different grid inside the grid, you might say – where each tree becomes something like a legal document, marking the outer boundaries of a lost landholding.

Of course, both of these examples together bring to mind the lost airports of Los Angeles, those geographies of aerial experience that now sit buried and all but forgotten beneath millions of tons of pavement throughout the greater L.A. region.

Other such examples are easy to come by – but their interest, for me, never dissipates. Whether it's the lost rivers of London still giving shape to the street plan above (or lost streams of Manhattan turning into underground fishing ponds), there are remnant geographies and ghostly templates everywhere.

In fact, as I recently wrote in an introduction to photographer Shaun O'Boyle's forthcoming book Modern Ruins: Architectural Monuments of the Mid-Atlantic – definitely check it out upon publication in 2010 – this even includes our own bodies: forgotten anatomies still make themselves known through the structure and layout of our nerves and bones.

But Rome, Los Angeles, London – these urban examples simply give our ghostly ancestors architectural shape.

Comments are moderated.

If it's not spam, it will appear here shortly!

Interesting because you can see that successive "templates" mark the endings of one era and the beginning of another. Might we say that the death of a vibrant city starts when the addition of new templates is abandoned (or made almost impossible, as is the case with much of Rome)?

A spot you might enjoy visiting is Capalbio, about an hour and a half drive up the coast from Rome. It's a small, fortified city in southern Tuscuny, that has been effectively killed through gentrification (ultra rich people buying the 15 or so residencies in the town from dying Italians and using them as vacation homes) and the complete abandonment of new construction within the small city itself. New construction around the town has transferred the most of population outside the city walls and turned the place into a ghost museum of sorts throughout most of the year.

It's hard to argue for the kind of wholesale destruction that goes on every year in Tokyo or Beijing, but some new, well-thought out changes in a city fabric can be good from time to time.

And if you make it to Capalbio, get the wild boar, it's delicious.

great post. Los Angeles has many phantom templates, especially those of hotels torn down to make way for progress or parking lots. At Crescent Heights and Sunset, you will find the footprint of the Garden of Allah hotel, now a mini mall. The fascinating is that the now empty spot determined the development of the surrounding commercial district, nightclubs and other hotels. The same will be said of the recently demolished Ambassador Hotel. Other hotels, historic landmarks and commercial development were situated to be next to the Ambassador.

Enjoy your time in Rome. It's a wonderful place.

Perhaps the most obvious ichnofossils of old cities are those left by railways, visible in the street plan as a line with an abnormally low number of roads crossing it. As a modest example, consider the stretch of the Edgware, Highgate and London Railway which once linked Edgware and Mill Hill Broadway stations (roughly speaking); over a distance of about a mile, it's crossed by just one road.

The same method can detect old canals, and also major sewers and buried aqueducts, which tend not to have things built on them.

A similar method, applied to aerial photos of East Anglia, easily finds old wartime airbases dotted all over the countryside, their runways now reduced to unusually-shaped field boundaries.

Post a Comment