|

|

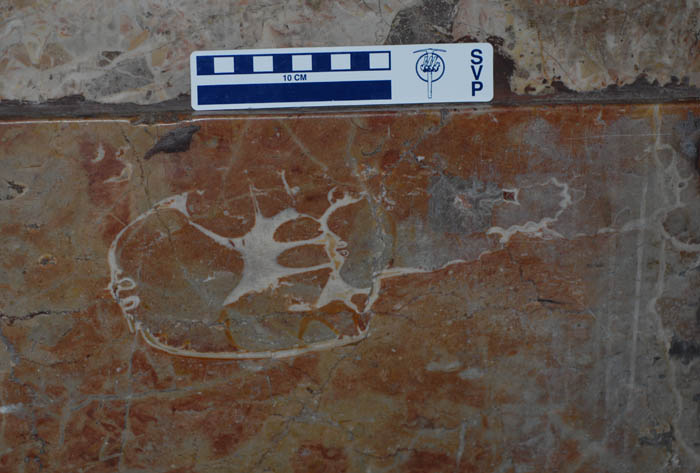

[Image: Photo courtesy of Andrea Tintori and Discovery News]. [Image: Photo courtesy of Andrea Tintori and Discovery News].

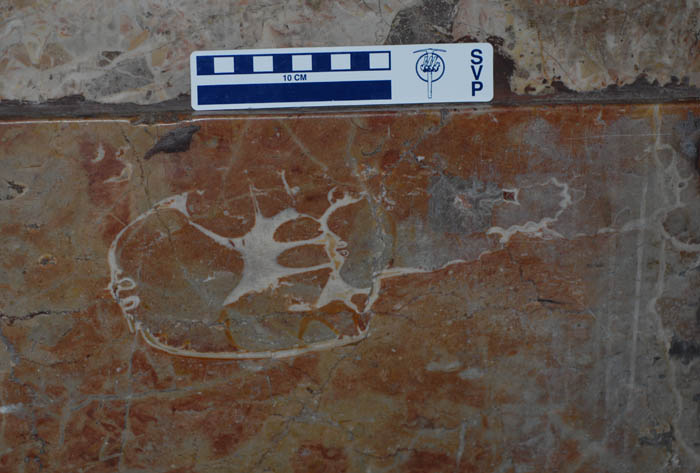

I love this story: the polished rock walls of a Catholic church in northern Italy have been found to contain the skull of a dinosaur. "The rock contains what appears to be a horizontal section of a dinosaur’s skull," paleontologist Andrea Tintori explained to Discovery News. "The image looks like a CT scan, and clearly shows the cranium, the nasal cavities, and numerous teeth.”

The skull itself was hewn in two; "indeed," we read, "Tintori found a second section of the same skull in another slab nearby."

[Image: Photo courtesy of Andrea Tintori and Discovery News]. [Image: Photo courtesy of Andrea Tintori and Discovery News].

The rock itself—called Broccatello—comes from a fossil-rich quarry in southern Switzerland and dates back to the Jurassic. According to the book Fossil Crinoids, "The Broccatello (from brocade) was given its name by stone masons; this flaming, multicoloured 'marble' has been used in countless Italian and Swiss baroque and rococo churches"—implying, of course, that other fossil finds are waiting to be found in Alpine baroque churches. "In the quarries of Arzo, southern Switzerland," the book continues, "crinoids [the fossilized bodies of ancient marine organisms] account for up to half of the bulk of the Broccatello, which is usually a few metres thick."

In any case, to figure out exactly what kind of dinosaur it is, the rock slab might be removed from the church altogether for 3D imaging in a lab; a new piece of Broccatello rock, mined from southern Switzerland, could be use as its replacement.

The larger idea of discovering something historically new and even terrestrially unexpected in the rocks of a city, or in the walls of the buildings around you—as if the most important fossil site in current geology might someday be the rock walls of a ruined castle and not a cliff face or gorge—brings to mind recent books like Richard Fortey's fantastic Earth: An Intimate History, with its geological introduction to sites like Central Park, Stories in Stone: Travels Through Urban Geology, and the Geologic City Reports (Parts 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6) by Friends of the Pleistocene. These latter research files present New York City through the lens of its lumpen underpinnings, focusing on bedrock, mineral veins, and salt, not the city's cultural districts or ethnic history.

But, of course, the H.P. Lovecraftian overtones of this story—a monstrous skull in a church wall—are too obvious not to mention: an easy scenario for imagining whole plots and storylines in which the ancient forms of an unknown species are discovered hidden in cathedral masonry, opening previously unimagined horizons of time and radically revising theories of the history of life on earth.

I just absolutely love the idea that a piece of architecture can become a site for paleontological research, framing an unlikely forensic study of the earth's biological past.

[Image: A fenced-off, back alley security stair in Toronto, via Google Street View; view larger]. [Image: A fenced-off, back alley security stair in Toronto, via Google Street View; view larger].

A link on Twitter from Andrew Lovett-Barron led me to this otherwise innocuous fenced-in back alley staircase in Toronto, pictured here via Google Street View ( view larger).

There's something oddly compelling about this minor architecture of out-of-place private access—as if implying that buildings could begin blocks and blocks away from where they actually rest in urban space, splayed out into the neighborhoods around them like chain-linked octopi, reaching out with stairways, doors, and catwalks across the roofs and back streets of the city. A Home Depot vernacular stretched to Berlin Wall-like proportions.

You don't like your address, you simply hurl a chain-linked access stair up over and out to whatever street you prefer—and you enter there, turning a key and stepping into a steel maze of steps and ladders, cantilevered walkways and pillared decks. Fifteen minutes later, passing over and beneath ribbons of other parallel geographies, looping down alleys and nesting briefly on thin platforms in the canopies of trees, walking alone in this isolated cocoon like a private enclave in the city, you're home.

Another story I meant to link here long ago is this real estate listing for an entire Scottish archipelago.

For £250,000—approximately $398,000—you can be the owner of "a wonderful and remote island group... a small archipelego centred around two main islands 25 miles north east of Lerwick, Shetland and extending to about 600 acres in all." It comes complete with a "private airstrip" and seasonal wild flowers.

Perhaps you want to establish a writers' residence. Perhaps you're fed up. Perhaps you want to declare a private city-state. Or perhaps you simply want to reinvigorate the struggling private island market.

Whatever the case may be, "a charter flight can also be arranged from Tinwall just to the north of Lerwick."

[Earlier on BLDGBLOG: Buy a Map, Buy a Torpedo-Testing Facility, Buy a Fort, Buy a Church, and Buy a Silk Mill].

[Image: Photo by Barney Peterson, courtesy of the San Francisco Chronicle]. [Image: Photo by Barney Peterson, courtesy of the San Francisco Chronicle].

Something I meant to post three few weeks ago, before October became the Great Lost Month of constant busyness and over-commitment, is the story of a 70-ton relief map of California, unseen by the public for half a century, that has been re-discovered in San Francisco, sitting in "an undisclosed location on the city's waterfront."

[Image: Photo by Barney Peterson, courtesy of the San Francisco Chronicle]. [Image: Photo by Barney Peterson, courtesy of the San Francisco Chronicle].

In its time, the map was considered far too marvelous for simply cutting up and storing—but that's exactly what's happened to it. It was as long as two football fields and showed California in all its splendor, from Oregon to Mexico, with snow-capped mountains, national parks, redwood forests, a glorious coastline, orchards and miniature cities basking in the sun. It was made of plaster, wire, paint, and bits of rock and sand. In the summer of 1924, Scientific American magazine said it was the largest map in the world. However, we read, "The problem with the map is simple: it is huge and would cost a lot of money to move, restore and display it. The last estimate was in the range of $500,000. And that was 30 years ago. It is a classic white elephant, too valuable to scrap, but too expensive to keep."

And, today, it's not going anywhere: "The Port of San Francisco has no plans to be anything but stewards of its storage, and no one else has come forward in half a century to rescue the map." If you have half-a-million dollars or so, and heavy moving equipment at your disposal, then perhaps it could soon be yours.

(Thanks to Steve Silberman for the link. In the archives: San Francisco Bay Hydrological Model; Buy a Torpedo-Testing Facility, Buy a Fort, Buy a Church, and Buy a Silk Mill].

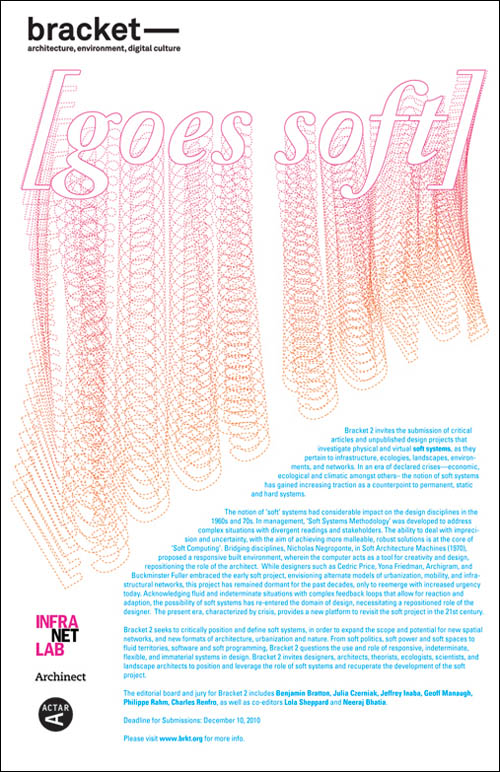

Just a quick reminder that you have till December 10 to submit to Bracket 2, published by Actar, Archinect, and InfraNet Lab: Bracket 2 invites the submission of critical articles and unpublished design projects that investigate physical and virtual soft systems, as they pertain to infrastructure, ecologies, landscapes, environments, and networks... Bracket 2 seeks to critically position and define soft systems, in order to expand the scope and potential for new spatial networks, and new formats of architecture, urbanization and nature. From soft politics, soft power and soft spaces to fluid territories, software and soft programming, Bracket 2 questions the use and role of responsive, indeterminate, flexible, and immaterial systems in design. Bracket 2 invites designers, architects, theorists, ecologists, scientists, and landscape architects to position and leverage the role of soft systems and recuperate the development of the soft project. Check out InfraNet Lab and the Bracket website for more info. Keep your eye out, as well, for InfraNet Lab's forthcoming Pamphlet Architecture installment, Coupling: Strategies for Infrastructural Opportunism.

Perhaps a short list of speculative mechanisms for future archaeological research would be interesting to produce.

[Image: A toy antique oscilloscope by Andrew Smith, courtesy of Gadget Master and otherwise unrelated to this post]. [Image: A toy antique oscilloscope by Andrew Smith, courtesy of Gadget Master and otherwise unrelated to this post].

Ground-scanners, Transparent-Earth ( PDF) eyeglasses, metal detectors, 4D earth-modeling environments used to visualize abandoned settlements, and giant magnets that pull buried cities from the earth.

Autonomous LIDAR drones over the jungles of South America. Fast, cheap, and out of control portable muon arrays. Driverless ground-penetrating radar trucks roving through the British landscape.

Or we could install upside-down periscopes on the sidewalks of NYC so pedestrians can peer into subterranean infrastructure, exploring subways, cellars, and buried streams. Franchise this to London, Istanbul, and Jerusalem, scanning back and forth through ruined foundations.

Holograph-bombs— ArchaeoGrenades™—that spark into life when you throw them, World of Warcraft-style, out into the landscape, and the blue-flickering ancient walls of missing buildings come to life like an old TV channel, hazy and distorted above the ground. Mechanisms of ancient light unfold to reveal lost architecture in the earth.

[Image: An LED cube by Pic Projects, otherwise unrelated to this post]. [Image: An LED cube by Pic Projects, otherwise unrelated to this post].

Or there could be football-field-sized milling machines that re-cut and sculpt muddy landscapes into the cities and towns that once stood above them. A peat-bog miller. Leave it operating for several years and it reconstructs whole Iron Age villages in situ.

Simultaneous milling/scanning devices that bring into being the very structures they claim to study. Ancient fortifications 3D-printed in realtime as you scan unreachable sites beneath your city's streets.

Deep-earth projection equipment that impregnates the earth's crust with holograms of missing cities, outlining three-dimensional sites a mile below ground; dazed miners stumble upon the shining walls of imaginary buildings like a laser show in the rocks around them.

Or a distributed iPhone app for registering and recording previously undiscovered archaeological sites (through gravitational anomalies, perhaps, or minor compass swerves caused by old iron nails, lost swords, and medieval dining tools embedded in the ground). Like SETI, but archaeological and directed back into the earth. As Steven Glaser writes in the PDF linked above, "We can image deep space and the formation of stars, but at present we have great difficulty imaging even tens of meters into the earth. We want to develop the Hubble into, not away from, the earth."

Artificially geomagnetized flocks of migratory birds, like " GPS pigeons," used as distributed earth-anomaly detectors in the name of experimental archaeology.

[Image: "GPS pigeons" by Beatriz da Costa, courtesy of Pruned]. [Image: "GPS pigeons" by Beatriz da Costa, courtesy of Pruned].

So perhaps there could be two simultaneous goals here: to produce a list of such devices—impossible tools of future excavation—but also to design a museum for housing them.

What might a museum of speculative archaeological devices look like? A Mercer Museum for experimental excavation?

(Thanks to Rob Holmes and Alex Trevi for engaging with some of these ideas over email).

[Image: An old asylum and its floorplan, courtesy of the University of Massachusetts at Dartmouth, otherwise unrelated to the present post]. [Image: An old asylum and its floorplan, courtesy of the University of Massachusetts at Dartmouth, otherwise unrelated to the present post].

We recently looked at the phenomenon of trap rooms, but that same idea came to mind again while reading about an interestingly architectural anxiety.

Amongst the many illnesses pushed to the limit by schizophrenic judge Daniel Paul Schreber—a figure who should be familiar to all readers of Deleuze & Guattari—was a kind of architectural paranoia. That is, Judge Schreber suffered an "anxious concern," as Victoria Nelson explains in her book The Secret Life of Puppets, "about the physical layout of the clinics in which he was housed (whose floor plans he includes in the Memoirs) and his occasional conviction that he was in a room that 'does not tally with any one of the rooms known to me' in the asylum."

He was inside the building, sure—but he was inside something else, an architectural circumstance he could neither abstractly understand nor spatially fathom. Perhaps, we might say, it was a trap room: a space neither here nor there, off the plan entirely, part of the very structure it will remain forever outside of.

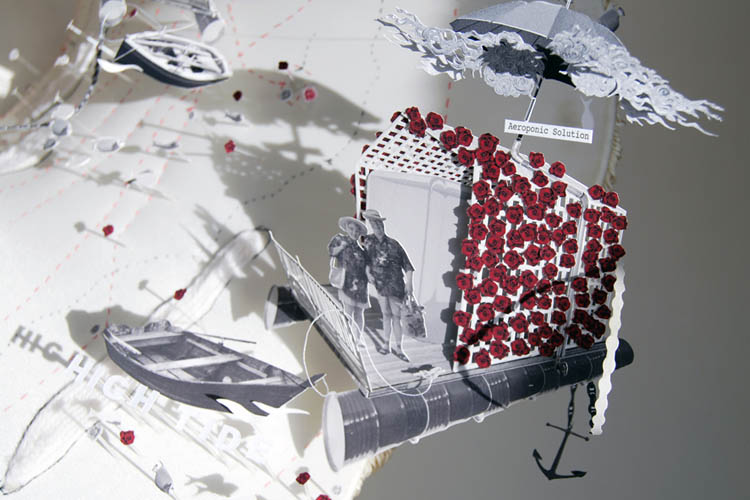

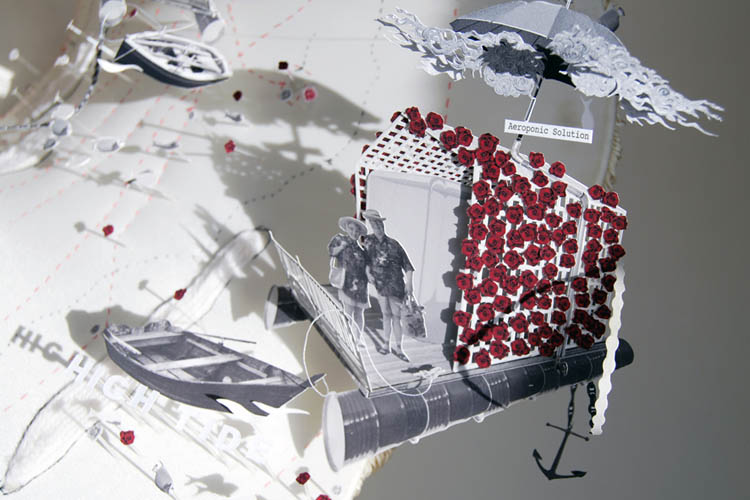

[Image: From "The Migration of Mel and Judith" by Thomas Hillier].

Thomas Hillier [Image: From "The Migration of Mel and Judith" by Thomas Hillier].

Thomas Hillier, of Emperor's Castle fame, has sent in a newly documented but chronologically older project of his called " The Migration of Mel and Judith."

" The Migration of Mel and Judith," Hillier writes, "was the pre-cursor to The Emperor’s Castle and my first real exploration into using narrative as the vehicle for generating and scrutinizing my architectural ideas. It was also where I began using craft-based techniques and 2/3-dimensional assemblage to illustrate the design process."

The Migration, though, is not only an entire storyline packaged inside a beautifully realized, miniature architectural world—it's also told inside a lampshade.

[Images: From "The Migration of Mel and Judith" by Thomas Hillier]. [Images: From "The Migration of Mel and Judith" by Thomas Hillier].

Mel and Judith, Hillier explains, are "a recently retired couple from Croydon who have decided to give up on their life in London’s third City and travel Europe," looking for a place to touch down for a while (and for better weather).

[Images: From "The Migration of Mel and Judith" by Thomas Hillier]. [Images: From "The Migration of Mel and Judith" by Thomas Hillier].

Soon enough, though, they get homesick—and the architectural transformation of their caravan-home begins: To combat thier longing they slowly adapt and customise their caravan-house to feel a little more like home. Walls of the caravan become aroma filled bricks of white bread, especially made by Mel & Judith themselves. Other adaptations include the pebbledash façade reminiscent of their Croydon abode. A green lawn-carpet that is much cooler underfoot than the hot Marbella sand and when it gets too hot there's always the sprinkler system and snow-chimney. The couple's mobile slice of English domesticity becomes all but entombed beneath the ornament of personal nostalgia.

[Images: From "The Migration of Mel and Judith" by Thomas Hillier]. [Images: From "The Migration of Mel and Judith" by Thomas Hillier].

This, too, steeped in English nostalgia, becomes too staid for them, and the couple decides to leave Europe altogether, alighting for the more exotic climes of Luxor, Egypt.

[Image: From "The Migration of Mel and Judith" by Thomas Hillier]. [Image: From "The Migration of Mel and Judith" by Thomas Hillier].

There, they settle "on a small, uninhabited island situated on the River Nile, where in their weird and wonderful ‘Do-It-Yourself’ English manor Mel brews beer in his bathtub-brewery whilst Judith bakes rose-bread in the bread-garden." Their island comes alive during the holiday season creating an English retreat in the middle of Luxor, a retreat that lures in English tourists with the opportunity to be surrounded by the sights, sounds and smells of home. The smell of roses and freshly baked bread drift through the air whilst the temptation to drink beer (which is illegal in Luxor) is impossible to resist. Maps of riverine estuaries have thus been sewn into the lampshade alongside windfarms, fishing boats, photo-collages, and even a portrait of Princess Diana.

[Images: From "The Migration of Mel and Judith" by Thomas Hillier]. [Images: From "The Migration of Mel and Judith" by Thomas Hillier].

If you pull back, though, and look at the whole project within its physical and visual frame, the self-enclosed curling world of the lampshade adds a wonderfully anti-perspectival, frilly concavity to the couple's journey. These latter scenes become both explosive and disorienting.

Like the spaceships in Stanley Kubrick's film 2001, the walls of their representational frame simply turn and turn, bringing us over and over again back through the same space, as if unwilling to let go of what's come before. Here, that space is asprawl with tidal flats and marshlands, fishing spots and coves. The couple, living now in Luxor, welcome visitors, dry their clothes aboard the boat deck, catch some afternoon sunlight, and grow old together, retired into this deliberately over-nostalgic world of their own making, constantly cycling back in memory through their shared past.

They have built a frame to fit themselves within, as if to give their lives narrative completion.

[Images: From "The Migration of Mel and Judith" by Thomas Hillier]. [Images: From "The Migration of Mel and Judith" by Thomas Hillier].

Check out The Emperor's Castle, meanwhile, if you haven't seen it already, and then click through to Hillier's website.

There are still a few hours—lasting till 8pm EST today—to participate in this week's Glass House Conversation on the political future of cities.

The comments have really hit on some great and very wide-ranging points, including, but by no means limited to, thoughts from Enrique Ramirez, Nicola Twilley, Matthew Battles, Ana María León, and David Gersten. The city as legal actor; the city as myth, described by Italo Calvino; the city as historical environment shaped by the proportions of the human body; the urban slum as a radically privatized development.

Being the host of the discussion this week, I would love to see a flurry of activity there in the last few hours; at 8pm EST tonight, it's all over!

Coincidentally, Foreign Policy's most recent issue proclaims that " The age of nations is over. The new urban age has begun." Perhaps skim that article on your way over to the Glass House Conversations, and then feel free to chime in.

While finalizing my slides for tonight's lecture at SCI-Arc, I was reading again about one of my favorite topics: trap streets, or deliberate cartographic errors introduced into a map so as to catch acts of copyright infringement by rival firms.

[Images: A "trap street" on Google Maps, documented by Luistxo eta Marije]. [Images: A "trap street" on Google Maps, documented by Luistxo eta Marije].

In other words, if a competitor's map includes your "trap street"—a fictitious geographic feature that you've invented outright—then you (and your lawyers) will know that they've simply nicked your data, giving it a quick redesign and trying to pass it off as their own.

But this strategy of willful cartographic deception is not always limited to streets: there can be trap parks, trap ponds, trap buildings.

And trap rooms.

Earlier this week, I was reading about the rise of internal navigation apps for mobile phones, apps that will help you to find your way through otherwise bewildering internal environments. Large shopping malls, for instance, or unfamiliar subway stations.

From the New York Times: A number of start-up companies are charting the interiors of shopping malls, convention centers and airports to keep mobile phone users from getting lost as they walk from the food court to the restroom. Some of their maps might even be able to locate cans of sardines in a sprawling grocery store. Whichever company can upload the most floorplans before everyone else will, presumably, have quite an economic advantage. So how could you protect your proprietary map sets? What if you're the only company in the world with access to maps of a certain convention center or sports stadium or new airport terminal—how could you keep a rival firm from simply jacking your cartography?

[Image: Photo by Laura Pedrick for The New York Times]. [Image: Photo by Laura Pedrick for The New York Times].

Introduce false information, perhaps: trap halls, trap stairs, trap attics, trap rooms. Nothing sinister—you don't want people fleeing toward an emergency stairway that doesn't exist in the event of a real-life fire—but why not an innocent janitorial closet somewhere or a freight elevator that no one could ever access in the first place? Why not a mysterious door to nowhere, or a small room that somehow appears to be within the very room you're standing in?

It seems to be a mapping error—but it's actually there for copyright protection. It's a trap room.

On one level, I'm reminded of a minor detail from Joe Flood's recent book The Fires, where we read that John O'Hagan, New York City's Fire Commissioner, used to drive around town with blueprints of local buildings stored in the trunk of his car. If there was ever a fire in one of those structures, and his men would have to find their way through smoke-filled, confusing hallways, O'Hagan would have the maps. But is there a kind of Fire Department iPhone app? Could this be downloaded by everyday citizens and used in the event of emergency? What about a Seismic App for earthquake-prone cities like Los Angeles? Going into any building becomes a considerably safer thing to do, as your phone automagically downloads the relevant floorplans. Perhaps buildings known to be fire hazards, or known to be earthquake-unsafe, are somehow red-flagged as a warning before you step inside. (In such a context, the first person to become Mayor on foursquare of every earthquake-unsafe building in Los Angeles wins cult status amongst certain social groups).

But I'm also curious about less practical things, such as what cultural, even psychological, effects the presence of trap rooms might actually have. Games could be launched, the purpose of which is to find and occupy as many trap rooms as possible. New paranoias emerge, that the room featured above your apartment on the new app you just downloaded is not really there at all; it's a trap room. You can't sleep at night, worried that you actually have no neighbors, that you're the last person on earth and every building around you is a dream. There are panic attacks and feelings of unreality, that no map can be trusted, that you've been living in a trap building all along. An Atlas of Trap Rooms is then released, with a foreword by Kevin Slavin.

These and other subtle geographies—trap architectures—awaiting detection all around us.

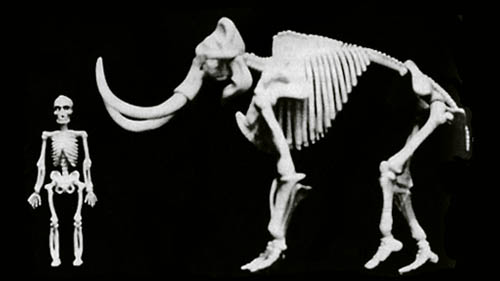

In her excellent book The First Fossil Hunters, author Adrienne Mayor explains, in fascinating detail, how Classical myths of giants, dragons, titans, heroes, and other ill-formed monstrous beings often stemmed from a misunderstanding of the fossil record. After all, it was not at all infrequent for people of the time to have "striking personal experiences with giant skeletons that weathered out of the ground in Asia Minor," Mayor writes, a place "where strange and immense skeletons emerge from the sand." And, with no particular reason to assemble all those gigantic bones into animal forms with which humans had no direct experience, the bones were, instead, simply fashioned together to form titanic heroes. Gods on earth. Monstrous ancestry.

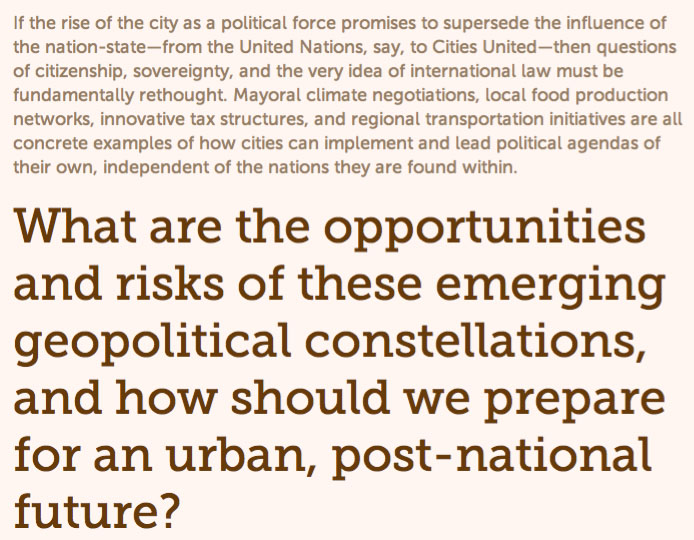

A mastodon skeleton like this, for instance, seen here in its proper assembly—

[Image: From The First Fossil Hunters by Adrienne Mayor]. [Image: From The First Fossil Hunters by Adrienne Mayor].

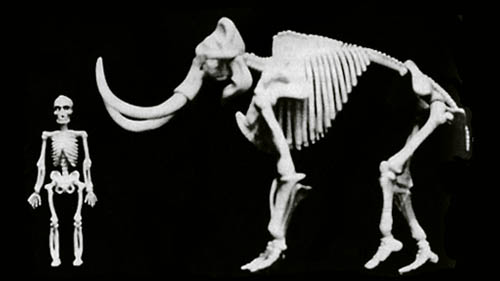

—was pieced together, instead, with Herculean proportions, towering over the human figure beside it.

[Image: From The First Fossil Hunters by Adrienne Mayor]. [Image: From The First Fossil Hunters by Adrienne Mayor].

Heroes, titans, giants: eventually, in a time before human history, Mayor explains, a mythic war between the oversized dwellers of the Earth and the Gods themselves took place, called the Gigantomachy. Explosive battles left incomprehensible body parts scattered all over the land masses, where they were gradually buried by sand or stratigraphically entombed inside rocky cliffs.

Then humans came along, unversed in today's anatomical principles, and assembled these giant bones into a lost and mutant history for themselves. And there you have Hercules, for instance, a mutant being accidentally assembled from the remnant skeletons of other creatures.

While I'm announcing things, I also want to give a heads up to anyone in the Los Angeles area that I'll be lecturing on Wednesday evening, October 13th, over at SCI-Arc, speaking on the subject of " Quadraturin and Other Architectural Expansionary Tales." I'll be delving into the long-running subtheme on this site of the role of architectural ideas in poetry, myth, comics, and fiction, from the ancient to extreme futurity.

From " trap streets" in London and the fiction of China Miéville to the folklore of The First Fossil Hunters and myths of Alexander's Gates—to, of course, Quadraturin—by way of Franz Kafka, Mike Mignola, Rupert Thomson, 3D-printing bees, haunted skyscrapers, neutrino storms, the Cyclonopedia, and much more, the talk will be a quick rundown of both the narrative implications of architecture and the architectural implications of specific storylines.

It's free and open to the public, and there's an insane amount of parking, so hopefully I will see some of you there. Here's a map. Things kick off at 7pm.

For the next five days, I'll be hosting and moderating an online discussion as part of the Glass House Conversations, sponsored by the Philip Johnson Glass House in New Canaan, Connecticut.

Every week this autumn, the Glass House Conversations have presented one question, posed by a new host each week, for general discussion online; previous queries have come from designers, writers, architects, critics, and educators, including 2x4, Steven Heller, John Maeda, Alice Twemlow, Alice Rawsthorn, Alissa Walker, and many more.

Click through to read the specific question I'm asking, and feel free to chime in; hopefully we can generate a good exchange over there throughout the week (note that the commenting function closes Friday evening).

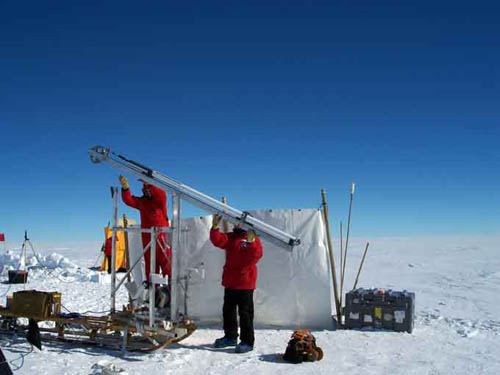

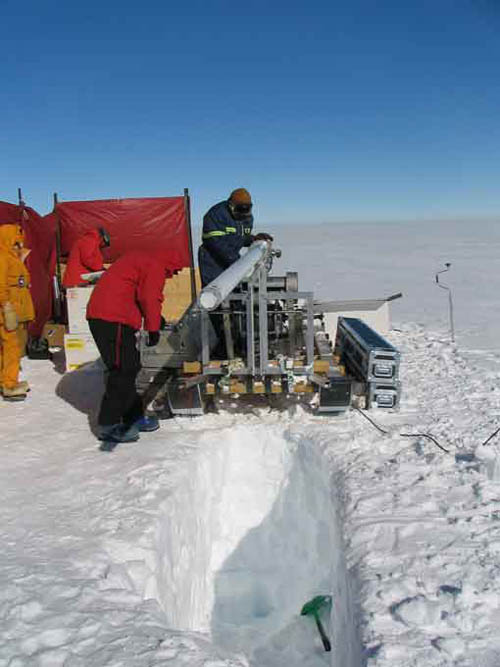

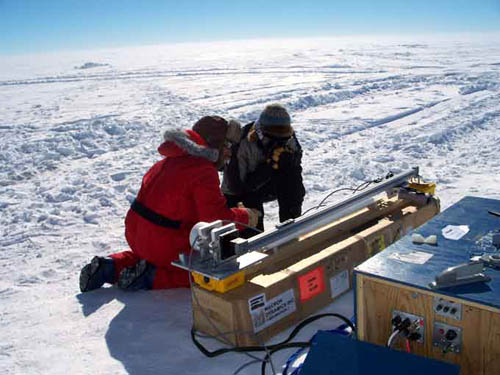

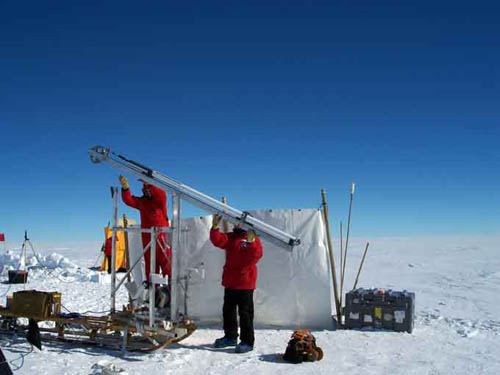

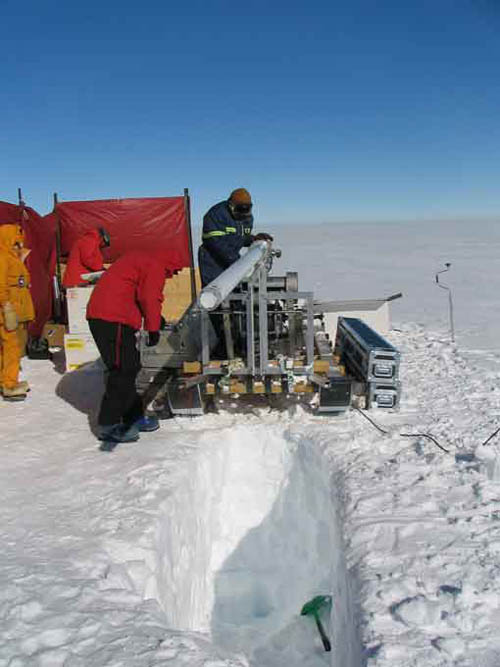

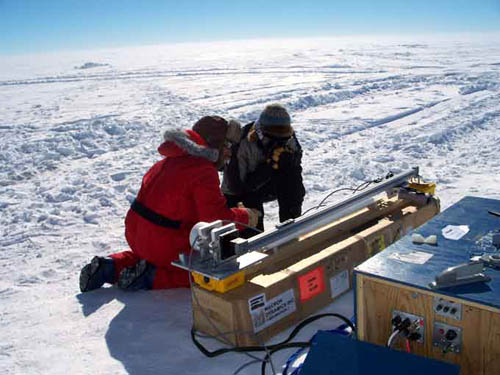

[Image: From the 2006-2007 U.S. ITASE expedition to Antarctica].

Edible Geography [Image: From the 2006-2007 U.S. ITASE expedition to Antarctica].

Edible Geography has a fun interview up this morning with glacial scientist Paul Mayewski, director of the Climate Change Institute at the University of Maine. The interview is remarkable not only for its descriptions of the technicality of drilling, shipping, preserving, and studying ancient ice cores removed from landscapes as far afield as Greenland and Tibet, but also for Mayewski's confession that unneeded ice cores are sometimes melted down and drunk by the scientists.

[Image: From the 2006-2007 U.S. ITASE expedition to Antarctica]. [Image: From the 2006-2007 U.S. ITASE expedition to Antarctica].

"But, you know," he clarifies, "it’s not as if we have a lot of ice lying around and we drink the water on a regular basis. We are pretty careful to restrict it to pieces that we know we don’t need for any measurements, and that come from places where they could be repeated if need be. We have to be sure that they’re not valuable to anybody. And we only use them for special events—we don’t drink it very often."

[Images: From the 2006-2007 U.S. ITASE expedition to Antarctica]. [Images: From the 2006-2007 U.S. ITASE expedition to Antarctica].

These special events include wedding receptions, where shavings of ancient ice, dropped into water, bubble and pop like champagne, Mayewski explains: Probably the most exciting thing about it is when you have real ice—that’s where the snow has been gradually compacted and eventually formed into ice, and the density has increased. When that happens, if the ice is old, it will often trap air bubbles in it. Those air bubbles can contain carbon dioxide from ten thousand years ago or even a hundred thousand years ago. And when you put an ice cube of that ice in a glass of water, it pops. It has natural effervescence as those gas bubbles escape. You get a little a puff of air into your nostrils if you have your nose over the glass. It’s not as though it necessarily smells like anything—but when you think about the fact that the last time that anything smelled that air was a hundred thousand years ago, that’s pretty interesting. Atmospheres trapped for a half-a-million years suddenly freed, as wedding guests inhale these vaporous paleoarchives.

[Image: From the 2006-2007 U.S. ITASE expedition to Antarctica]. [Image: From the 2006-2007 U.S. ITASE expedition to Antarctica].

The whole interview, though long, is a quick and good-spirited read.

|

|

[Image: Photo courtesy of Andrea Tintori and Discovery News].

[Image: Photo courtesy of Andrea Tintori and Discovery News].  [Image: Photo courtesy of Andrea Tintori and Discovery News].

[Image: Photo courtesy of Andrea Tintori and Discovery News].

[Image: A fenced-off, back alley security stair in Toronto, via

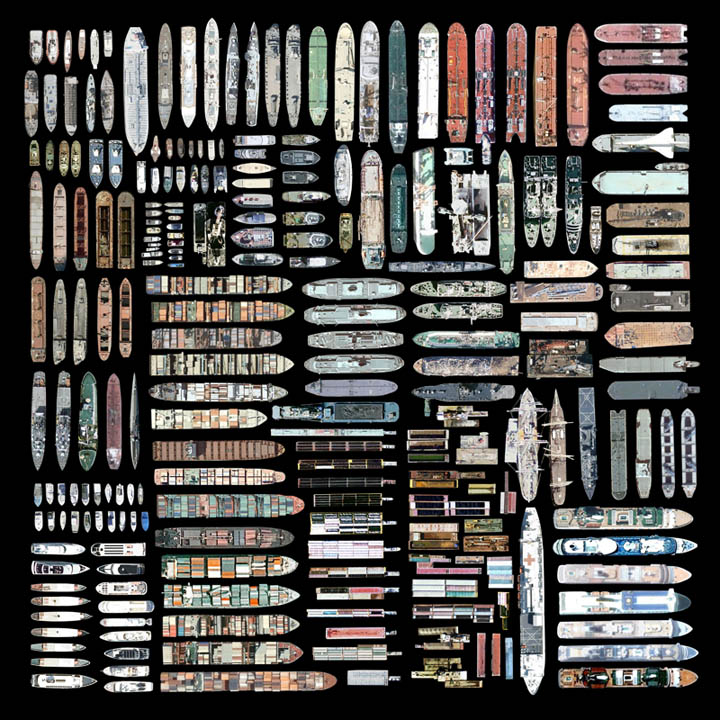

[Image: A fenced-off, back alley security stair in Toronto, via  [Image: Oceangoing ships clipped and stitched from Google Maps by artist

[Image: Oceangoing ships clipped and stitched from Google Maps by artist

[Image: Photo by Barney Peterson, courtesy of the

[Image: Photo by Barney Peterson, courtesy of the  [Image: Photo by Barney Peterson, courtesy of the

[Image: Photo by Barney Peterson, courtesy of the  Just a quick reminder that you have till December 10 to submit to

Just a quick reminder that you have till December 10 to submit to  [Image: A toy antique oscilloscope by Andrew Smith, courtesy of

[Image: A toy antique oscilloscope by Andrew Smith, courtesy of  [Image: An LED cube by

[Image: An LED cube by  [Image: "GPS pigeons" by

[Image: "GPS pigeons" by  [Image: An old asylum and its floorplan, courtesy of the

[Image: An old asylum and its floorplan, courtesy of the  [Image: From "The Migration of Mel and Judith" by

[Image: From "The Migration of Mel and Judith" by

[Images: From "The Migration of Mel and Judith" by

[Images: From "The Migration of Mel and Judith" by

[Images: From "The Migration of Mel and Judith" by

[Images: From "The Migration of Mel and Judith" by

[Images: From "The Migration of Mel and Judith" by

[Images: From "The Migration of Mel and Judith" by  [Image: From "The Migration of Mel and Judith" by

[Image: From "The Migration of Mel and Judith" by

[Images: From "The Migration of Mel and Judith" by

[Images: From "The Migration of Mel and Judith" by

[Images: From "The Migration of Mel and Judith" by

[Images: From "The Migration of Mel and Judith" by

[Images: A "trap street" on Google Maps, documented by

[Images: A "trap street" on Google Maps, documented by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  While I'm announcing things, I also want to give a heads up to anyone in the Los Angeles area that I'll be lecturing on Wednesday evening, October 13th, over at

While I'm announcing things, I also want to give a heads up to anyone in the Los Angeles area that I'll be lecturing on Wednesday evening, October 13th, over at  Every week this autumn, the

Every week this autumn, the  [Image: From the 2006-2007

[Image: From the 2006-2007  [Image: From the 2006-2007

[Image: From the 2006-2007

[Images: From the 2006-2007

[Images: From the 2006-2007  [Image: From the 2006-2007

[Image: From the 2006-2007