|

|

[Image: Constructing with BeadBricks by Rizal Muslimin, courtesy of Brickstainable]. [Image: Constructing with BeadBricks by Rizal Muslimin, courtesy of Brickstainable].

The winners of this year's Brickstainable design competition were announced last week, and two of the technical award-winners are actually quite interesting.

[Images: BeadBricks by Rizal Muslimin, courtesy of Brickstainable]. [Images: BeadBricks by Rizal Muslimin, courtesy of Brickstainable].

I'm particularly taken by a submission called BeadBricks by Rizal Muslimin, described as able to facilitate the design of microclimates "in and around buildings" by allowing variable levels of porosity in the facade. BeadBricks could thus allow architects "to modulate the environmental factors including sunshine, wind, thermal mass, and evaporative cooling."

The system, Muslimin explains, consists of "two bricks (A and B) with four basic rules that can generate shape in one, two and three dimensional space." Further, "the bricks are decorated with a pattern that can generate various ornaments by rotating them along its vertical or horizontal axis."

[Image: Constructing with BeadBricks by Rizal Muslimin, courtesy of Brickstainable]. [Image: Constructing with BeadBricks by Rizal Muslimin, courtesy of Brickstainable].

The overall technical winner is also worth checking out: the EcoCeramic Masonry System, a "Recombinant and Multidimensional" molded terracotta brick devised by Kelly Winn and Jason Vollen.

[Image: The EcoCeramic Masonry System by Kelly Winn and Jason Vollen, courtesy of Brickstainable]. [Image: The EcoCeramic Masonry System by Kelly Winn and Jason Vollen, courtesy of Brickstainable].

As Brickstainable describes it, their brick system "showcases the ability to look at new ceramic-based wall assemblies. Strategies include thermal dynamics, self-shading, moisture reduction, hydroscopic, evaporative, and termite behavior studies."

[Images: The EcoCeramic Masonry System by Kelly Winn and Jason Vollen, courtesy of Brickstainable]. [Images: The EcoCeramic Masonry System by Kelly Winn and Jason Vollen, courtesy of Brickstainable].

Meanwhile, a related project comes to us from designer Dror Benshetrit, who recently invented his own modular system, called QuaDror. On the other hand, it's not really a "brick"; Fast Company describes it as "a structural joint that looks a little like a sawhorse, but can fold flat, making it both stunningly sturdy, remarkably flexible, and aesthetically pleasing." Check out the video:

The suggested uses for QuaDror "include support trestles for bridges, sound buffer walls for highways, a speedy skeleton for disaster or low-income housing, and quirky public art."

All in all, I would love to see more exploration with all three of these ideas, and I look forward to seeing all of them utilized in projects outside the design studio.

(Thanks to Thomas Rainwater for the tip about QuaDror and to Peter Doo for keeping me updated on Brickstainable).

[Image: By San Rocco]. [Image: By San Rocco].

In December 2010, San Rocco, an Italian magazine dedicated to contemporary spatial culture, produced the two images seen here. They were created in response to a move by the Italian Minister of the Interior to extend an anti-hooliganism ban—originally intended as a way to protect the city from violent sports fans—and using it, instead, as a means for spatially preventing "political rallies."

San Rocco have thus shown both Venice and Rome closed off behind museum-like turnstiles and security barriers, or what the magazine calls "efficient technological devices to regulate access to public space."

[Image: By San Rocco]. [Image: By San Rocco].

Even divorced from their political context, though, these images are provocative illustrations of another phenomenon: that is, the museumification of urban space, particularly in Venice, a city steadily losing its population.

The idea that we might someday see the urban cores of historic European cities simply abandoned by residents altogether and turned, explicitly, into museums, surrounded by pay-as-you-go turnstiles, does not actually seem that far-fetched.

(Spotted via Critical Grounds).

[Image: From the forthcoming Pamphlet Architecture #32 by Stasus]. [Image: From the forthcoming Pamphlet Architecture #32 by Stasus].

The forthcoming Pamphlet Architecture #32, on the theme of "resilience," will be authored by Matt Ozga-Lawn and James A. Craig of Stasus, a young design firm based in Edinburgh and London.

[Images: From the forthcoming Pamphlet Architecture #32 by Stasus]. [Images: From the forthcoming Pamphlet Architecture #32 by Stasus].

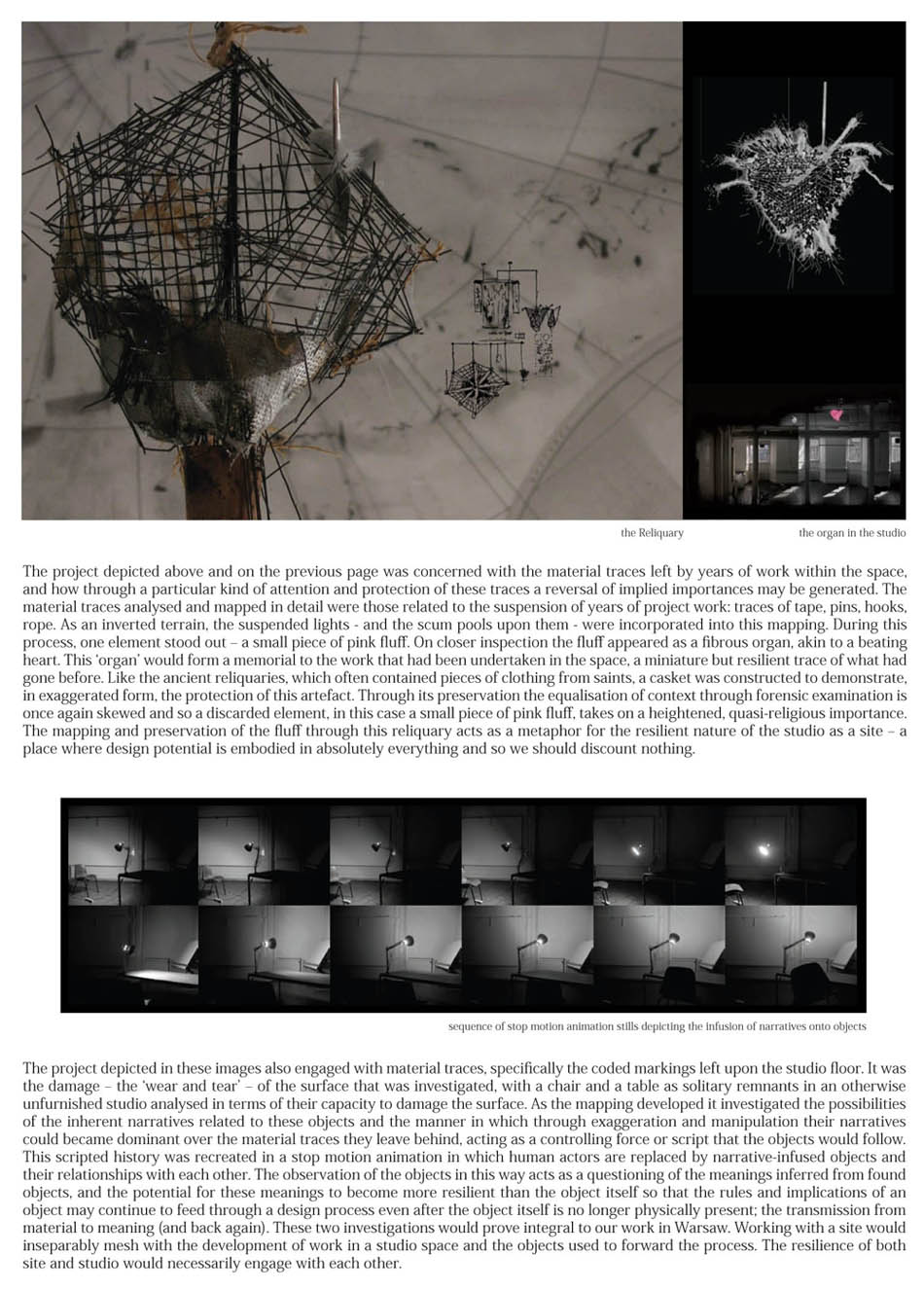

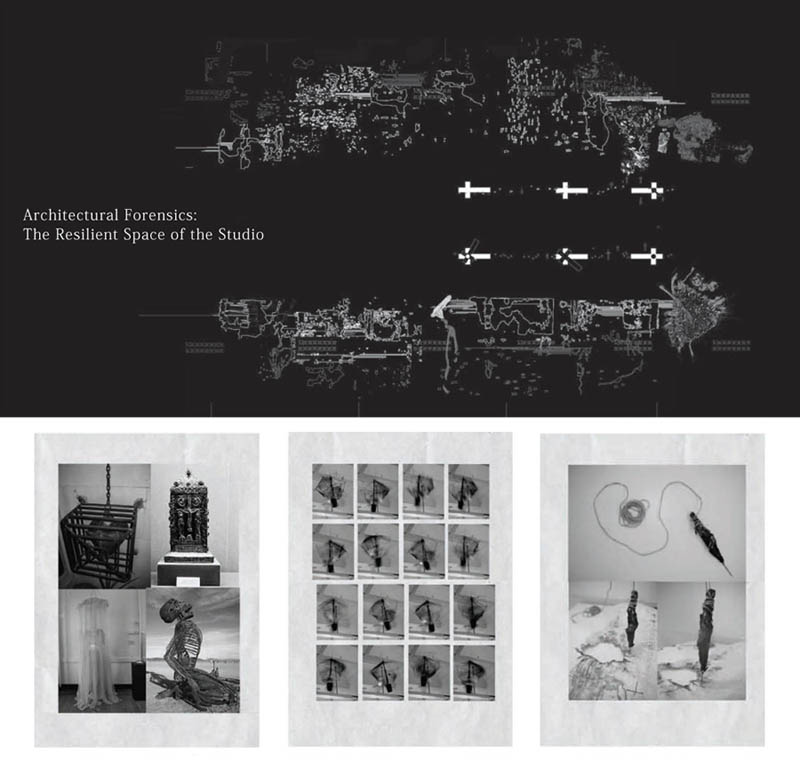

The pamphlet, which will explore a series of post-industrial sites in the city of Warsaw—"a desolate area of disused freight rail tracks, commercial lots, gasometer buildings and other industrial apparatus," as the architects describe it—is more explicitly narrative than the other pamphlets that have been most recently published.

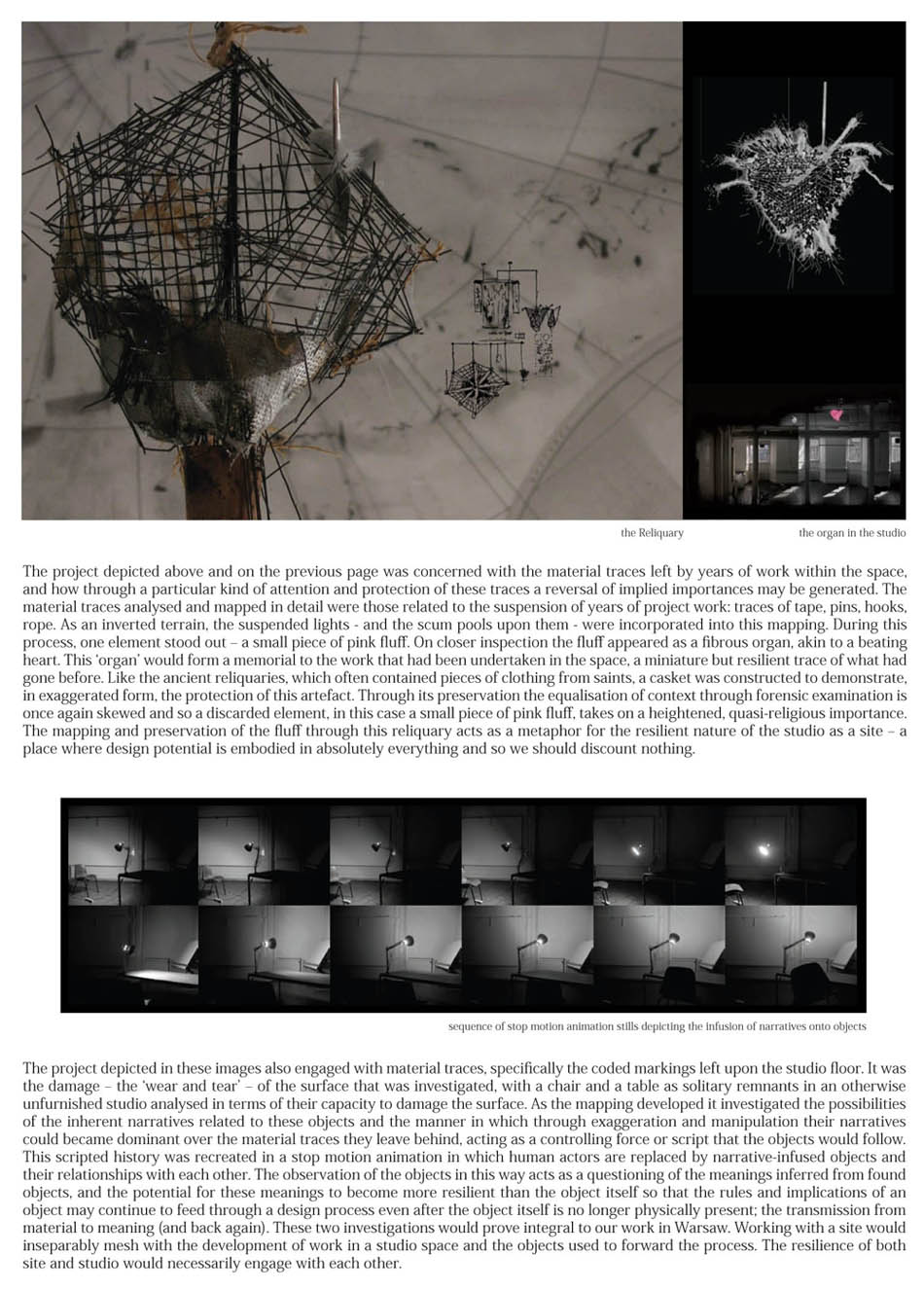

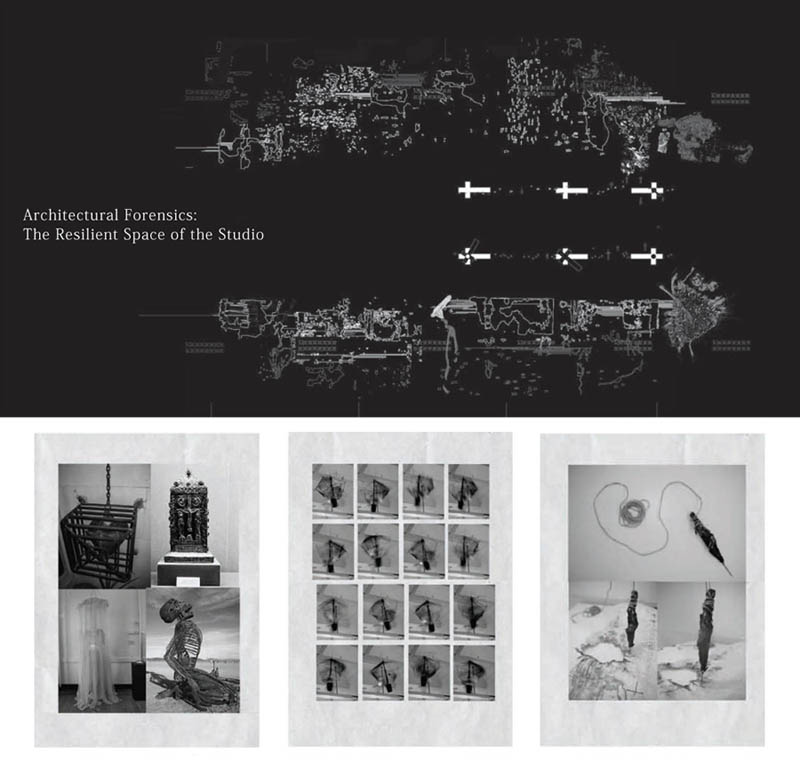

"The scope and intent of our book," Stasus writes, citing such influences as Piranesi and Andrei Tarkovsky's film Stalker, "is to highlight the importance of forgotten landscapes in our cities and the potentialities that can be extracted from them." A sprawling, unplanned city centre threatens a desolate landscape that still embodies many resilient aspects of the city. In many ways, the "value" of this landscape, though barren, could be said to exceed that of the new centre. The profound additional meanings inherent to a disused rail track in Warsaw, for example, eclipse the meanings inherent to a city block of financial skyscrapers. Rather than replace or erase these attributes, we aimed to augment the resiliency of the meanings that were embodied in every element of the landscape we stumbled across. As our design process progressed this methodology spread to every aspect of our thinking. Within this urban landscape "on the edge of oblivion," as they describe it, "frozen, awaiting the imminent state of transition from one state to the next," they focused on a series of found objects and particular locations—a kind of readymade architectural forensics of the city.

[Images: From the forthcoming Pamphlet Architecture #32 by Stasus]. [Images: From the forthcoming Pamphlet Architecture #32 by Stasus].

Their chosen strategy seems to have arisen directly from a course taught at the University of Edinburgh by professor Mark Dorrian.

As Dorrian himself explains, his students were urged "to set aside all familiar hierarchies, and recognize that dust, a discarded piece of paper or a scratch on the floor is as important as a window, cornice, column or door. We are in a situation in which everything counts—or at least in which we can discount nothing." Overlooked minor objects, apparently without use, and peripheral spaces of the city, apparently without residents, were thus taken as central to the course's architectural intentions.

[Images: From the forthcoming Pamphlet Architecture #32 by Stasus]. [Images: From the forthcoming Pamphlet Architecture #32 by Stasus].

For their part, Stasus interpreted this design brief as requiring the use of narrative in order to help them reveal their site's future spatial possibilities. In their own words: Once identified, the design process takes the form of a testing and investigation of the properties inherent to these existing landscapes of possibilities. The more resistant certain elements are to transformation, deletion, or manipulation, the more they are worked into the design process and become adapted within and integral to design "outputs." The approach is therefore vastly different from a blank-paper methodology. Rather than creating our own clearing for design work, we aim to identify the most resilient elements within our field of exploration. These may be meanings passed through material context, implied mythical narratives, incidental connotations, historical and pre-historical implications. "Our design process could therefore be described as an investigation of the resilient qualities of that which exists, a navigation of resilient landscapes," they summarize.

And it is the work that came out of that course that thus forms the conceptual backbone for the work that will soon appear as Pamphlet Architecture #32.

[Images: Derelict landscapes and optical devices scaled up to the size of megastructures, by Stasus]. [Images: Derelict landscapes and optical devices scaled up to the size of megastructures, by Stasus].

In his introductory essay for the pamphlets, Dorrian suggests that Stasus's work "draws upon the strange imagined half-lives of obsolescent and anachronistic things" that are "charged with the future."

Put another way, abandoned objects, locations, and spaces have a particular kind of architectural potential energy, a lack of precise definition that allows them to hover somewhere between promise and realization; however misleading it might actually be, then, dereliction implies a unique capacity for transformation—an ability to assume radically new spatial characteristics in the future—whilst simultaneously presenting what we could describe as fossils of an earlier world, one that has long since disappeared or ceased to operate.

[Images: From the forthcoming Pamphlet Architecture #32 by Stasus]. [Images: From the forthcoming Pamphlet Architecture #32 by Stasus].

In any case, I've included some preliminary images from the pamphlet here, as well as some project images by Stasus; for more, check out Stasus's website and keep your eye out for the Pamphlet itself, which I assume will be out sometime in the autumn.

[Image: Giovanni Fontana's 15th-century "castle of shadows," from a paper by Philippe Codognet]. [Image: Giovanni Fontana's 15th-century "castle of shadows," from a paper by Philippe Codognet].

In a book published nearly 600 years ago, in the year 1420, Venetian engineer Giovanni Fontana proposed a mechanical construction called the Castellum Umbrarum, or "castle of shadows."

Philippe Codognet describes the 15th-century machine as "a room with walls made of folded translucent parchments lighted from behind, creating therefore an environment of moving images. Fontana also designed some kind of magic lantern to project on walls life-size images of devils or beasts." Codognet goes on to suggest that the device is an early ancestor of today's CAVE systems, or virtual reality rooms—an immersive, candlelit cinema of moving screens and flickering images.

[Image: "Homer, the Classic Poets," by Gustave Doré, from Canto IV of The Inferno]. [Image: "Homer, the Classic Poets," by Gustave Doré, from Canto IV of The Inferno].

Novelist Zachary Mason's Lost Books of the Odyssey has been described by The New York Times as "dazzling... an ingeniously Borgesian novel that’s witty, playful, moving and tirelessly inventive."

As Slate's John Swansburg describes it, the book is a fictional anthology of "Homeric apochrypha—versions of the Odysseus story that circulated in the time before Homer but were left out of the epic as we came to know it." Yet "Mason's enterprise never devolves into a mere high-concept exercise," Swansburg adds. And I agree: the book's constantly shifting short narratives offer a kind of stratigraphic road-cut straight to the contested origins of Western mythology, where a storm-wracked, war-torn archipelago is ceaselessly crossed by a homesick husband fighting to return to his family—only Mason has taken these elements and cross-wired them, creating a dreamlike, parallel landscape of new heroic sequences, echoes, and myths.

In the following interview, Zachary Mason speaks to BLDGBLOG about his book; its use of the archipelagic landscapes of ancient Greece for new, combinatorial ends; the algorithmic templates underlying much of his fiction; his current work on Artificial Intelligence; the future of automated construction technologies, including 3D-printing, a theme explored in Mason's most recent work; other possible narrative directions for further rewritings of The Odyssey (including a version set in the Caucausus Mountains, with, as Mason describes it below, "a huge system of unreliable, unmapped and essentially creaky rope-bridges strung up between the peaks"); and much more. We spoke by phone.

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for The Adventure of Odysseus and the Tale of Troy, Padraic Colum's own retelling of The Odyssey].

• • •

BLDGBLOG [Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for The Adventure of Odysseus and the Tale of Troy, Padraic Colum's own retelling of The Odyssey].

• • •

BLDGBLOG: I’d like to start with one of the most memorable images in the book, that of " Agamemnon's Fortress." Could you describe that briefly?

Zachary Mason: In that chapter, the Greeks, having no building materials except for the timbers of their ships, and expecting the siege to last a long time, have excavated their forward base in the sand in front of Troy.

This chapter has the structure of a fairy tale, or something out of the Arabian Nights. It starts with Agamemnon's sense of helplessness; for all his armies and his heroes he can't take a single city, which leads him also to reflect on the extent of his ignorance, so he calls together his three wisest counselors and, not being one for half-measures, asks them to explain, essentially, everything in the world. Three times he asks them, and each time they come back with a denser and perhaps pithier solution, and with each iteration more time passes.

The underground base becomes first a city, then a network of cities, that keep getting deeper as the old cities crumble and are used only for storage chambers and secret passages, and, all this time, Troy is only about half a mile away. By the end of the story Troy has been abandoned, so there’s no further reason for the Greeks to be there, but they still are, and they're still digging deeper.

Part of what I was doing was taking the structure of a fairy tale—often there are three questions, animals, obstacles or what have you—and making the progression between the iterations exponential, rather than constant, so there’s a drastic acceleration.

Also, there's something fascinating about this improvised, temporary, and quite uncomfortable underground base becoming permanent and entrenched, and going ever deeper, starting to dominate the lives of the residents with its deranged logic. It's reminiscent of an ants’ nest, or the World War II eras quonset huts still in use at SRI.

BLDGBLOG: Or Kafka’s " Burrow", another story of tunneling. What I like about the image is its dichotomy between the aboveground walled fortress of Troy, with its stone walls and permanent streets and houses, and its long-term sense of history, compared to the underground maze of the invading Greeks, constantly turning this way and that and digging deeper into the earth. It’s a nice juxtaposition.

Mason: Troy is the absence of possibilities, in a sense; it’s just there and the Greeks can’t do anything about it, no matter how much they try. In the sand, though, there are infinite possibilities, all of them fairly useless.

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for The Adventure of Odysseus and the Tale of Troy, Padraic Colum's retelling of The Odyssey].

BLDGBLOG [Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for The Adventure of Odysseus and the Tale of Troy, Padraic Colum's retelling of The Odyssey].

BLDGBLOG: You also describe how, when the sand walls collapse, the Greeks implement laws that say the soldiers can’t excavate or uncover things that have been buried. They’re forced to avoid their own past, in a sense, and keep digger new tunnels. It’s like a legislatively enforced amnesia, or a living archive that refuses to excavate itself.

Mason: I liked the idea that they would become trapped by their own superstitions: prevented from doing the rational thing—as far as planning went—and obliged by this unfortunate belief to keep digging themselves in deeper.

In a way, it's the opposite of amnesia, if you think of the collapsed chambers as preserved. As though we were forbidden to repair collapsed or damaged buildings on the surface, and cities become theme-parks of stratified decay.

BLDGBLOG: There’s another image in the book that really caught me: Ilium, “death’s city,” full of “uncountable mausoleums” and constructed from bones. “The high walls of Death’s city became the ubiquitous background of the Greek’s dreams,” you write.

Mason: In that chapter Troy has become Death's city, and it is implied that all of Hades is contained within its walls. I imagined Death's city as a place of levels, reaching down forever; it goes so deep, that not even its inhabitants have seen all of it, which somehow seems to gel with the way the representation of Death as an object of obsessive focus.

In this story, Menelaus eventually defeats and overthrows Death, and though he intends to destroy his city, but he end up doing no more than taking Death's place, and adding new levels to the already infinite levels of the city.

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for The Adventure of Odysseus and the Tale of Troy, Padraic Colum's retelling of The Odyssey].

BLDGBLOG [Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for The Adventure of Odysseus and the Tale of Troy, Padraic Colum's retelling of The Odyssey].

BLDGBLOG: I’m curious, pulling back a level, how a particularly evocative city description or landscape description can, in and of itself, achieve something on a narrative level that other rhetorical devices often aren’t able to or have a harder time accomplishing. It interests me, for instance, that if your book was set in a very different place or geography—in central Illinois, say, wandering from town to town—those facts alone, before characterization even kicks in, would hugely affect the mood or tone of the story. Part of the imaginative appeal of The Odyssey itself, I would say, has a lot to do with the archipelagic landscape it takes place within; if Odysseus had just wandered around the Caucasus Mountains, from peak to peak, instead of island to island, then the story’s cosmic overtones—wherein each island is its own micro-cosmic world, with its own sequences of experience—would have been achieved only in a quite different rhetorical way.

Mason: [ laughs] I’m imagining The Odyssey set in Illinois—how the Trojan War would be a fight for one particular bit of plain amidst otherwise completely identical expanses of plain, and how that would add a sense of futility to Odysseus's homeward journey—he weeps when he finally sets foot on Ithaca, which is fifty hectares of absolutely undistinguished farmland.

Here's an idea: set The Odyssey in the Caucasus, but with a huge system of unreliable, unmapped and essentially creaky rope-bridges strung up between the peaks. The valleys are full of bandits, and hardship, and take a long time to navigate—but, though the ropes are faster, no one knows quite why they're there, or their connectivity. Then you'd have something that feels at least a little like The Odyssey.

A nice thing about islands, as opposed to regular old landscape, is that they seem completely knowable. With an island, one could have a clear view of all of the elements in play in whatever narrative, and of the island's history, and of the full significance of everything. One's understanding of a continent is necessarily hand-wavey, and things are probably changing faster than one can keep track of them.

There was an older version of the Lost Books—or, at any rate, another book that ended up getting folded into what eventually became the Lost Books—which was going to be much more explicitly geographical. Every story was going correspond to an island, and the elements of those islands would be specified by a combinatoric system. I made up a table of elements, and I was duly working my way through the possible combinations, but it turned out to be very, very difficult to make this work; I couldn't finish it, though you can still see echoes from time to time.

I think art tends to turn out best under moderate constraint; the combinatoric system was probably a little too strong. But I kind of like the way the character of the old, never-quite finished book shows up in the Lost Books (there's actually more than one unfinished ghost-book lurking in the Lost Books), because its interesting when there are multiple patterns that partially describe, in this case, a book, but where none of them completely describe it. Its a little like complexity theory—too much order and you get banal rigidity, but too little and you get chaos, and the interesting things are on the boundary between the two.

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for The Adventure of Odysseus and the Tale of Troy, Padraic Colum's retelling of The Odyssey].

BLDGBLOG [Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for The Adventure of Odysseus and the Tale of Troy, Padraic Colum's retelling of The Odyssey].

BLDGBLOG: Are you drawn to things like the Oulipo, or other sorts of literary games?

Mason: I’ve always been drawn to Oulipo. I have one life in math and science, and another in literature, so Oulipo is compelling as the intersection between the two. On the other hand, Oulipan games don't always work. There are a few products of Oulipo that are brilliant, and some that are interesting, and more that are the literary equivalent of musical scales.

The book was, in its original conception, intensely Oulipan, but I couldn't get it work that way, so I ended up relaxing the constraints I had imposed on myself, lest I end up with something that felt like a sterile exercise rather than an organic whole.

So you might say that, for me, Oulipo is a good starting point but not a good finishing point.

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for The Adventure of Odysseus and the Tale of Troy, Padraic Colum's retelling of The Odyssey].

BLDGBLOG [Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for The Adventure of Odysseus and the Tale of Troy, Padraic Colum's retelling of The Odyssey].

BLDGBLOG: Is the final sequence of chapters arranged for narrative effect, then, or is it based on some other sort of underlying structure or combinatorial path?

Mason: In an early version of the book I did use an algorithm to order the chapters. In those days, each chapter was associated with a handful of keys—broad themes like "time" and "the gods" and "revenge" and so forth. I wrote a program that used simulated annealing to order the book in a more-or-less optimal way, where optimality was defined as maximizing the number of overlapping keys between adjacent chapters. The intent was to produce an ordering where there was always a strong sense of continuity between chapters, but where the nature of that continuity varied with every boundary.

In the end, I didn’t like the ordering the algorithm produced, and realized that there were actually other rules I wanted to follow, some of which didn't lend themselves to formalization, so I ended up arranging the chapters by hand. I try to alternate long and short chapters, and its good when adjacent chapters rhyme, thematically; also, the book now starts off by establishing the kind of recombinatoric game I'm playing with The Odyssey, and then, as you get toward the end, that pattern breaks down, and you get all sorts of strange things— The Odyssey interpreted as a chess manual, for instance.

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for The Adventure of Odysseus and the Tale of Troy, Padraic Colum's retelling of The Odyssey].

BLDGBLOG [Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for The Adventure of Odysseus and the Tale of Troy, Padraic Colum's retelling of The Odyssey].

BLDGBLOG: The chess manual chapter—“Record of a Game”—is fantastic. Could you describe that chapter briefly and explain its conceit?

Mason: “Record of a Game” is a chapter that explains how The Iliad is not, in fact, an epic, but an ancient chess manual. This chapter explains that chess radiated out from India and took on locally idiosyncratic forms in most Indo-European cultures; in ancient Greece, it assumed a form in which the pieces, rather than being faceless icons, are strongly individuated. There were a few particular games that were considered to embody everything that was worth knowing about the game, and chess masters had to memorize those games precisely. Various mnemonics were added to make this task easier and eventually, to the uninitiated, the records of these games came to seem like heroic narratives, which was aided when the mnemonics were misinterpreted as epic clichés—Thetis being "trim-ankled," Achilles "fleet-footed" and so forth.

A lot of the book is about interpreting The Odyssey as a code, so that Homer's text is understood as a distortion of some underlying signal, and it is that signal, under various assumptions, that one is trying to infer. "Record of a Game" is perhaps the most extreme example of this, in that it explains away almost everything about The Iliad.

The coda to this chapter explains that The Odyssey is a sort of fictive chess manual, describing the motion of the pieces after the game has finished and the players have departed, in which the Odysseus piece is trying to get back to its home square. So it a sort of second-order game.

BLDGBLOG: Interpretation, here, becomes a form of paranoia—more an act of invention than one of reading.

Mason: There are some aspects of The Iliad that lend themselves almost eerily to this kind of interpretation—like the famous catalog of ships, which is also famously boring. In “Record of a Game,” it's explained that the catalog of ships is properly understood as a description of the opening in a chess game.

Then there are all the lists of killing—this warrior slew that warrior, and that warrior slew this other warrior—which is not, I think, hugely interesting in itself, but, if you look at it as a series of exchanges in the middle game, begins to make sense sense.

On the other hand, Homer has been what one might call exhaustively interpreted. You can sit alone in your living room and make up the craziest, most implausible theory about Homer that you can, and then go to Google, you’ll find that some serious person with solid academic credentials has dedicated his career to espousing your preposterous theory.

BLDGBLOG: [ laughs] Like Shakespeare wrote Homer.

Mason: Exactly.

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for The Adventure of Odysseus and the Tale of Troy, Padraic Colum's retelling of The Odyssey].

BLDGBLOG [Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for The Adventure of Odysseus and the Tale of Troy, Padraic Colum's retelling of The Odyssey].

BLDGBLOG: If that’s the case, do you see your own book as participating in, and thus continuing, this sort of interpretive culture? Or is it more of a parody?

Mason: It’s a bit of both. I was certainly aware of the exhaustive interpretation of Homer, and I guess I thought of the Lost Books as enabled by that, and somehow setting a cap on it, by being the logical culmination and maximum expression of this tendency. It's as though I was saying, "You call that interpretive chaos? I'll show you interpretive chaos!"

That said, I wasn’t trying to put Homeric interpretation out of business or make any big, stomping academic points. It just seemed like this tradition both suggested and licensed a really fun thing to do with the book.

And then, The Odyssey seems to lend itself uniquely to this kind of remixing, in that it's compelling at almost any granularity. The way its written is compelling in the details, but, at a coarser level, what one might call its language of imagery is powerful. The Odyssey retains considerable power even when reduced to a plot synopsis, which isn't true of many books—a plot synopsis of The Inferno or Lolita is unlikely to be hugely interesting. Cormac McCarthy's The Road might come close, but, really, it just has a single image. As I say this, it occurs to me that many Borges stories would still be compelling as a single paragraph precis.

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for The Adventure of Odysseus and the Tale of Troy, Padraic Colum's retelling of The Odyssey].

BLDGBLOG [Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for The Adventure of Odysseus and the Tale of Troy, Padraic Colum's retelling of The Odyssey].

BLDGBLOG: Stepping back a bit, your author bio refers to you as an Artificial Intelligence researcher, but I’m curious what that actually means.

Mason: The first thing to notice about AI is that there isn't any; in some sense, there’s been no real progress in the field. We don’t know much more about the computational character of cognition than we did in 1950. So I, like a number of people, am interested in trying new ways of approaching the problem. New kinds of computational models of perception and language are, I think, one promising path.

A particular interest of mine is computational models of design. Design problems are kind of a sweet spot, insofar as they offer deep domain richness, but they don’t too much background knowledge, which is very difficult to handle, computationally. You just need models of artifacts, and the way those artifacts are interpreted.

One of the problems with A.I. is that interacting with the world is really tough. Both sensing the world and manipulating it via robotics are very hard problems, and solved only for highly stripped-down special cases. Unmanned aerial vehicles, for instance, work well, because maneuvering in a big, empty, three-dimensional void is easy—your GPS tells you exactly where you are, and there's nothing to bump into except the odd migratory bird. Walking across across a desert, though, or, heaven help us, negotiating one's way through a room full of furniture in changing lighting conditions, is vastly more difficult.

BLDGBLOG: Saying this purely as a dilettante, it seems like there are at least two models of Artificial Intelligence. One of them is about spatial navigation, as you say, but another is more textual, or language-based. This latter version touches on things like the Turing Test, of course, but also on things like the text-mining industry, where they’ve developed intelligent software programs that can read through hundreds of thousands of pages in a flash and find the keywords or phrases that you’re looking for—which is different from a Google search.

Mason: Text-mining is well and good, but there’s a sense in which it’s not A.I. The programs don’t understand the text in any meaningful way. They manipulate it statistically, and, in that way, they’re able to accomplish things that appear intelligent—but there’s no actual comprehension.

You can take text analytics and that sort of thing up to a certain point, and you can get some pretty impressive results—Google works well—but there’s a hard boundary that you’re not going to be able to cross if you don’t have a full-fledged model of cognition.

Nobody’s figured out how to make that model, so there are hard limits on how far things like Google and text analytics can go. This is tacitly understood, for the most part (though I've spoken with some Googlers who have seemed guilty both of hubris and of not understanding A.I.'s history), but it’s bad business to admit it. So, when they say their algorithms are intelligent, or that their algorithms understand the text and so forth, its just fatuous marketing-speak.

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for The Adventure of Odysseus and the Tale of Troy, Padraic Colum's retelling of The Odyssey].

BLDGBLOG [Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for The Adventure of Odysseus and the Tale of Troy, Padraic Colum's retelling of The Odyssey].

BLDGBLOG: I’m curious how all this comes together in The Lost Books of the Odyssey. So far, we’ve talked about combinatorics, allegories, Artificial Intelligence, and the Oulipo, and I know that, for me, there were moments while reading the book when it felt almost as if a program had been fed certain narrative parameters— cave, cyclops, Odysseus, boat—and the remixed results became the Lost Books, as if it were the output of a demented A.I. program. Were you hoping to use the book itself as a model for computational literature?

Mason: There was a time in my life when I would have been very happy to have it suggested that my work was the output of a demented A.I. program—

BLDGBLOG: I meant that in a positive way!

Mason: A counter-question for you is: do you think you would have thought that if my bio hadn’t said that I worked with A.I.?

BLDGBLOG: Perhaps not. But, on another level, especially with a book like yours, doesn’t the author bio become a deliberate way to frame the book’s contents? It helps to flavor how a book is received and interpreted.

Mason: That’s a fair point. In fact, in the first edition of the book, I used a fake author bio. I claimed to be an archaeo-cartographer and paleo-mathematician at Magdalen College, Oxford, the holder of the John Shade Chair. Note that archaeo-cryptography and paleo-mathematics don't exist as disciplines, and John Shade is a character in a Nabokov novel. I was perhaps unreasonably pleased with this trick, not least because much of the book is about endless recursions of false and manipulative identity—so it seemed to fit, rather than being arbitrary hijinks.

I was persuaded to use a real biography for the FSG edition, and have since regretted it. My author-bio says I do A.I., because I thought it was an interesting hook, but it seems to color the way people approach the book now, and not necessarily in desirable ways. On the whole, I'd like the book to be read without reference to my biography. Perhaps I should really have gone beyond the bounds of the plausible and claimed to be a graduate of the Iowa Writer's Workshop, and that I now teach creative writing at a small Midwestern liberal arts school.

I've been sufficiently cranky about this that I've considered saying that, in fact, I'm just a writer, but there's another guy with the same name as me who is a computer scientist specializing in A.I. We met because we have similar gmail addresses, and sometimes get each other's mail. He was kind enough to read an early draft of my book, and, being a Borges fan, like disproportionately many well-read scientists, wondered how differently the book would read if it had been written by an A.I. guy. I thought that sounded like a good hook, and ran with it.

But, to answer your question more directly, I certainly wasn’t going for anything overtly combinatoric, or at least not after the book's very earliest days.

It sounds like you’re reacting to my preoccupation with what I might call the primes of the story. There are aspects of the Odyssey that seem essential, and these are few in number, just a handful of images. There’s a man lost at sea, an interminable war a long way behind him, and a home that’s infinitely desirable and infinitely far away. There’s the man-eating ogre in his cave; there are the Sirens with their irresistible song; there's the certain misery of Scylla and Charybdis.

I feel like these images are responsible for the enduring power of the story, and its survival, more than the particular details of, say, dialogue among the suitors, or what have you. I wanted to work directly with these primes, to present them in as powerful and stripped-down a way as possible, and to explore how they could interact, and how they could combine to make new forms. I suppose this kind of minimalist, reductive aesthetic does has a mathematical flavor.

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for The Adventure of Odysseus and the Tale of Troy, Padraic Colum's retelling of The Odyssey].

BLDGBLOG [Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for The Adventure of Odysseus and the Tale of Troy, Padraic Colum's retelling of The Odyssey].

BLDGBLOG: In the more recent fiction that you sent me, you’ve been exploring quite strong architectural and urban imagery. I’m curious to hear more about how urban imagery, in particular, features in your more recent fiction, and other ways that urban and architectural descriptions are being foregrounded in your work.

Mason: I sent you some fragments of a book, tentatively titled Void Star, in which architecture does feature rather prominently.

The book is set in the murkily indefinite future. Technology has improved, and robotics works much better, so much so that it has become a cheap, boring technology, and construction robots, in particular, are ubiquitous—they're essentially 3D printers scuttling around on insect-like legs. Right now, researchers are taking the first steps toward building robots where you can set them loose and they’ll assemble complicated structures—often, interestingly, mimicking the control principles used by social insects—and I thought how interesting it would be, and how different the world would look, if these things ever actually work.

Today, anybody can go to Home Depot or its equivalent and buy the materials to build a shed; but construction, on a large scale, is very expensive and reserved for wealthy organizations. It's a rare privilege to actually get to build something. If these robots exist, then architecture is democratized: anyone with a few bucks can build a structure to whatever specifications they like.

Once you have that, cities start to metastasize and grow. Favelas and other improvised and illegal shadow cities become marvelous, growing layer upon layer, like coral reefs.

Another architecturally salient aspect of Void Star is that, in the book, A.I.s exist, but they're not like anyone expected. They’re intelligent but not human; in fact, their minds and perspective and languages are so different that people can’t really talk to them—they're much more like Stanislaw Lem's Solaris than Commander Data, the Terminator, Agent Smith, or HAL. Despite this, they can still be useful—in design tasks, for instance. They write most of the world’s software, and do it very quickly—the amount of code in the world increases by many orders of magnitude, but nobody knows how it works. Software development becomes a process less of hacking code than establishing some sort of shared understanding with these strange, essentially foreign intelligences.

The A.I.s also design buildings, and they think so fast, and with such breadth, that their designs are more complete than is otherwise possible. Buildings become much more complicated, and better thought-out—in a sense, absolutely thought-out. The A.I. might consider, say, the light and the acoustics at every spot in the building at every time of day and every day of the year, and the kinds of relationships that you could then create between the experiences at these different locations. Also, because the machines have such fine-tuned control of the way buildings are constructed, they can implement design motifs that go down almost to the molecular level. In buildings as they are, there is, inevitably, unarticulated matter—a girder is just a girder, concrete is just concrete—but the machines could make their artifacts fractally ornate at every level. They would, in some sense, be complete artifacts.

It will be an interesting world.

• • •

[Image: Fractalized Greek ornamental motif]. [Image: Fractalized Greek ornamental motif].

Thanks again to Zachary Mason for taking the time to have this conversation. Pick up a copy of The Lost Books of the Odyssey, meanwhile, which came out in paperback last month, and see what you think.

Here's a quick rundown of some things you might want to attend, participate in, write for, keep your eye on, etc.

1) 1) The discussion series Humans, Robots and War continues at 4pm this afternoon with " Digitizing the Laws of War" at USC: "A panel of guests including David Kaye of UCLA School of Law, Edwin Smith of USC Gould School of Law, and political scientist Amy Eckert of Metropolitan State College of Denver will explore the legal and political ramifications of the rise of robotic warfare. Both the need to address legal agency in light of artificial intelligence as well as the increased capacity to report on events on the battlefield will be discussed. How robots fit into both jus in bello as well as jus ad bellum questions is the focus." A sequel of sorts takes place on April 7: " Robotics, Warfare and Humanity."

2) Also today, at 7pm, at the Arid Lands Institute in Burbank, Vinayak Bharne and Dilip da Cunha will participate in The Agency of Water: Scarcity, Abundance, and Design in Dialog, lecturing on, respectively, "Urbanism, Infrastructure & the Urban Water Crisis: Perspectives from Asia & the American Southwest" and "Negotiated Landscapes: Mississippi, Bangalore, and Mumbai."

3) As mentioned before, a forthcoming collection called Making a Geologic Turn, edited by Friends of the Pleistocene, is seeking contributions about, among many other things, how "contemporary artists, popular culture producers, and even philosophers are adding new layers of meaning and sensation to [the] 'geologic.'" Abstracts are due March 1, 2011.

4) The Heart of Texas Boundary Retracement takes place March 3-5, 2011, and it sounds fascinating: it "will be a modern-day search for original survey corners. (16 CEUs) By utilizing county record information, GLO field notes, working sketches and aerial photos, the original surveys can be positioned within a small search area. Licensed State Land Surveyors will be party chiefs to guide you through the process using information found on the ground. This area has not been bulldozed, chained or root plowed like many of the ranches in Texas, therefore providing a rare opportunity to find several of the original corners." The boundary retracement will take place on Wulff Cedar Creek Ranch, the geographic heart of Texas.

5) Thresholds 40 "invites projects, ideas, and beliefs in a variety of media, including scholarly papers, visual work, and philosophical treatises, that explore the dangerous and messy theme of the socially conscious project."

6) 6) Speaking of water, meanwhile, on April 1-2, 2011, the University of Pennsylvania will be hosting a symposium called In the Terrain of Water: "Water is everywhere before it is somewhere. It is rain before it is rivers, it soaks before it flows, it spreads before it gathers, it blurs before it clarifies. Water at these moments in the hydrological cycle is not easy to picture in maps or contain within lines. It is however to these waters that people are increasingly turning to find innovative solutions to the myriad water-related crises that catalyze politics, dynamics, and fears. Is it not time to re-invent our relationship with water—see water as not within, adjoining, serving or threatening settlement, but the ground of settlement? Could this be the basis of a new vocabulary of place, history, and ecology? And can the field of design, by virtue of its ability to articulate and re-visualize, lead in constructing this new vocabulary?" Check out their site for more information.

7) "The Ambience conference focuses on the intersections and interfaces between technology, art and design. The first international conference in the Ambience series was held in Tampere, Finland in 2005. In Tampere 2005, the basic theme was 'Intelligent ambience, including intelligent textiles, smart garments, intelligent home and living environment.' In Borås 2008, it was 'Smart Textiles—Technology & Design' and, in Borås 2011, it will be the new expressional crossroads where art, design, architecture and technology meet: digital architecture, interaction design, new media art and smart textiles." Abstracts for a special issue of Studies in Material Thinking are due by April 1, 2011.

8) From June 22-23, 2011, catch Tunnel Design & Construction Asia 2011 in Singapore.

9) "We are seeking contributions from all disciplines to an American Studies essay collection on Dirt. Dirt is among the most material but also the most metaphorical and expressive of substances. This collection hopes to bring together essays that explore how people imagine, define, and employ the various concepts and realities of dirt. What does it mean to call something dirty? How do we understand dirt and its supposed opposite, cleanliness? How do we explain the points at which we draw the line between clean and dirty, what we embrace and what we refuse to touch? Drawing on multiple disciplines we hope to uncover and foreground the (often unconscious) centrality of the metaphors and actualities of dirt to U.S. cultures, values, and lived experiences." Essays are due December 11, 2011.

(Thanks to Nicola Twilley, Javier Arbona, Jeremy Delgado, Catherine Bonier, and Mette Ramsgard Thomsen for the tips!)

For those of you in London, today was your last opportunity to stop by the old Shoreditch Tube Station for a scheduled viewing: the whole thing is up for sale, listed at £180,000.

[Image: The old Shoreditch Tube station is for sale; image and property info courtesy of Andrews & Robertson]. [Image: The old Shoreditch Tube station is for sale; image and property info courtesy of Andrews & Robertson].

"Situated at the junction with Code Street and Pedley Street adjacent to Allen Gardens," the auctioneers explain, "[t]he property is within a popular residential area with its many trendy shops, bars and restaurants." For instance, "Brick Lane is within easy walking distance and Old Spitalfields Market is close by."

The single-floor building, pictured above, courtesy of the auctioneers, "comprises a ticket office, a lobby area, store rooms, plant rooms and a WC." Owning a former Tube station with an address on Code Street would be an amazing thing, indeed. BLDGBLOG would move its offices there in a heartbeat.

(Thanks to Jim Stephenson for the tip! Earlier on BLDGBLOG: Buy an Archipelago, Buy a Map, Buy a Torpedo-Testing Facility, Buy a Fort, Buy a Church, Buy a Silk Mill).

[Image: From a cover by Mike Mignola for Hellboy: The Storm, courtesy of Dark Horse Comics]. [Image: From a cover by Mike Mignola for Hellboy: The Storm, courtesy of Dark Horse Comics].

For half a decade now, I've been an avid fan of the work of Mike Mignola, creator of Hellboy, the B.P.R.D., and Abe Sapien, among many others, including, most recently, the new series Witchfinder and Baltimore. When my wife and I moved back to California last August, the heaviest boxes were the ones I'd stuffed full of graphic novels by Mike Mignola, which I've been hoarding whenever money allows. It's become an addiction: the incredible old castle interiors and snowbound mountain landscapes of Conqueror Worm, the Mesoamerican design motifs emerging like mazes from pitch black walls of shadow in Seed of Destruction, the graveyards of ships wrecked on rocks before coastal citadels in Strange Places, and all of it shot through with Mignola's dark sarcasm and humor.

Mignola's work outlines an endlessly captivating world, somewhere between H.P. Lovecraft and Norse epics, Dracula—as rewritten by Jules Verne—and the Discovery Channel. Equal parts archaeology and horror fiction, Indiana Jones and The Thing, heretical mythology and conspiracy science, once Mignola's work digs its plot lines and landscapes into you, it seems impossible to shake.

The buildings, terrains, and spaces Mignola's plots take place within are equally extraordinary: there are remote, factory-like castles north of the Arctic Circle, wired floor-to-ceiling with arcane laboratory equipment; maritime plagues and New England shipwrecks; intelligent geological formations in space, larger than planets, signaling down to Army radar stations at the end of World War II; abandoned mines and ruined churches; Mayan fragments mounted on the luxurious, candlelit walls of Alpine mansions; Nazi conspiracies and fallen astronauts; derelict Victorian houses wrapped in fog on the coastal moor.

In addition to his prolific work as a graphic artist, Mignola has served as a visual consultant on three films by Guillermo Del Toro, each better than the previous: Blade II, Hellboy, and Hellboy 2: The Golden Army. With Christopher Golden, he is co-author of the recent novel Baltimore; he has drawn covers for Conan the Barbarian, X-Men, Aliens versus Predator, Superman, and dozens of others; and his Eisner Award-winning graphic novel, The Amazing Screw-On Head and Other Curious Objects, was republished in 2010.

[Image: A cover by Mike Mignola for B.P.R.D.: The Warning, courtesy of Dark Horse Comics]. [Image: A cover by Mike Mignola for B.P.R.D.: The Warning, courtesy of Dark Horse Comics].

Mike Mignola recently talked to BLDGBLOG about his interests, including H.P. Lovecraft, wartime landscapes, and houses on the verge of collapse, with a specific focus on what it means to draw spaces of horror and mythology. We spoke by phone.

• • •

BLDGBLOG: I’ve long been interested in how people outside of the architectural world use buildings, landscapes, cities, and other spaces as a way to frame mood or character. Your own work, from Hellboy and the B.P.R.D. to Abe Sapien and Baltimore, is full of ruined churches, old battlefields, houses with flooded basements, warped floors and empty attics, and other straightforwardly Gothic landmarks. What draws you to these particular building types and locations, and how do these settings then affect your plot lines and characters?

Mike Mignola: Well, I am unapologetically old-fashioned in my use of Gothic settings. Ever since I was a kid, when I read Dracula, I’ve just loved those kinds of places.

I have never done a story in a shopping mall because, even if I’m not drawing it myself, I don’t want to see somebody draw a shopping mall. In the Hellboy world, and in other things I’ve done, those places almost don’t exist. When I do Eastern Europe—and I’ve been to Eastern Europe, and I’ve seen the shopping malls and the god-awful housing projects and things, and there are horror stories that take place in there, I have no doubt—but I gravitate toward the classic, clichéd, spooky places, whether they truly exist in this world or not.

But that’s the world I want to live in, and it’s the world my characters live in.

[Images: (left) A cover from Hellboy: The Wild Hunt; (middle) from the cover of Rex Mundi by Arvid Nelson and Juan Ferreyra; (right) a cover from Hellboy: The Wild Hunt. All artwork by Mike Mignola, courtesy of Dark Horse Comics].

BLDGBLOG [Images: (left) A cover from Hellboy: The Wild Hunt; (middle) from the cover of Rex Mundi by Arvid Nelson and Juan Ferreyra; (right) a cover from Hellboy: The Wild Hunt. All artwork by Mike Mignola, courtesy of Dark Horse Comics].

BLDGBLOG: Beyond shopping malls, I’m curious if there are other sorts of anti-Mignola settings, so to speak—places where you just could never set a story, even if it’s just a bank in London.

Mignola: I’m not going to do any stories that I don’t want to draw—and, for the most part, those are places that also just aren’t particularly interesting for me to write about.

It’s interesting, because the spin-off book from Hellboy— B.P.R.D.—is written by another writer. I have some involvement there, but the books are written by somebody else. You look at that book now, and the current storyline takes place in a trailer park. It’s entirely made of the places I have no interest in writing about—but the other writer doesn’t have my overwhelming love of the Gothic. He’s a much more modern type of writer, so we differ on our choice of locations.

But, now, a haunted bank? You know, that would be cool—but it would have to be a really, really old bank. And preferably a bank that’s been abandoned for a bunch of years, so you have cobwebs and things. I just like those old, spooky settings.

[Images: Covers by Mike Mignola, from Lobster Johnson: The Iron Prometheus and Abe Sapien: The Drowning, courtesy of Dark Horse Comics].

BLDGBLOG [Images: Covers by Mike Mignola, from Lobster Johnson: The Iron Prometheus and Abe Sapien: The Drowning, courtesy of Dark Horse Comics].

BLDGBLOG: There’s a maritime undercurrent in much of your work, including Hellboy, Abe Sapien, and, of course, the plague ships of Baltimore. It's a kind of maritime Gothic—a world of shipwrecks and sea monsters and lighthouses on foggy coasts.

Mignola: Shipwrecks are great—but ships in general, even when they’re not wrecked, as long as they’re old school sailing ships, are wonderfully Gothic. I don’t know that I’ve done a lot of stories—if any stories—with ships that are 20th-century ships. I like the romance and the spookiness and the tragedy that goes with that old time sea travel. Those stories pertaining to ships are huge. I love them. They’re a big genre within ghost story fiction.

One of my favorite authors—a guy named William Hope Hodgson—most of his career, or a large chunk of his career, was writing supernatural ships-at-sea stories. There’s a romance in that old school, Gothic-y way to the world. And, basically, everything I love, I try to bring into my work. This world, or these different worlds that I’m creating, are entirely made of stuff that I love and think about.

Everything that I’m a fan of, I want to put into these worlds.

[Images: Photos by Fred R. Conrad, courtesy of The New York Times].

BLDGBLOG [Images: Photos by Fred R. Conrad, courtesy of The New York Times].

BLDGBLOG: Last summer, construction workers uncovered the remains of an old ship buried in the mud beneath the World Trade Center site in Manhattan, and some of the photos later printed in the New York Times, taken by Fred R. Conrad, were like something straight out of a Mike Mignola story. In some ways, it seemed like the perfect opening scene for a film version of Abe Sapien or for Hellboy 3—as if beneath, or even inside, the island of Manhattan we find this rotting, Gothic, semi-forgotten maritime history.

Mignola: Yeah, you know, I love history. I’m not a scholar—I’m not an historian—but it's mostly because I just don’t have time. There’s too much other stuff I’m trying to keep on top of. But I love that sense of the buried past.

[Image: From Hellboy: The Wild Hunt, written by Mike Mignola and Scott Allie; art by Duncan Fegredo and Patric Reynolds. Courtesy of Dark Horse Comics].

BLDGBLOG [Image: From Hellboy: The Wild Hunt, written by Mike Mignola and Scott Allie; art by Duncan Fegredo and Patric Reynolds. Courtesy of Dark Horse Comics].

BLDGBLOG: I want to go back to the idea of setting. Have you ever found yourself in a situation where a setting that you’ve devised for a certain storyline simply doesn’t work for Hellboy, say, so you have to use—or even invent—another character, or an entirely different plot, in order to use the architecture? In other words, how does setting—that is, how can architecture—affect plot and characterization, and vice versa?

Mignola: Well, part of the Baltimore series we’re doing now takes place on a World War 1 battlefield. I love that setting. It’s wonderfully rich in horror and drama—but it’s really hard for me to do a Hellboy story that takes place on a World War 1 battlefield. I could do it, and I’ve done stories like that, where it’s a time travel -slash- dream kind of thing—in fact, in an upcoming issue of Hellboy, I do have another character who I’ve tied to World War 1—but, to do it right, you need a World War 1 story.

So I came up with the Baltimore novel—and, now, the comic—to address that.

There’s also Victorian London, which I love. I came up with a Hellboy story once where he kind of time-traveled back to Victorian London—it seemed a little goofy to me—but I knew that I wanted to do Victorian London, so it was just a question of making a character who functioned in that world.

In a lot of cases, though, I am creating characters in order to see these places—these times, these settings. But, from the very beginning, I’ve known what kinds of stories I’ve wanted to do—so it’s also a question of finding the character who belongs to that world, as an excuse to draw that world.

[Images: Preview spreads from Witchfinder: In the Service of Angels. Art by Ben Stenbeck, story by Mike Mignola, courtesy of Dark Horse Comics. If this gets you hooked, purchase the book].

BLDGBLOG [Images: Preview spreads from Witchfinder: In the Service of Angels. Art by Ben Stenbeck, story by Mike Mignola, courtesy of Dark Horse Comics. If this gets you hooked, purchase the book].

BLDGBLOG: I’m curious about your work method, as far as nailing the details of these settings and landscapes. Do you travel a lot, watch a lot of movies, look at lots of photographs, talk to archaeologists—or it is really just an act of imagination?

Mignola: It's a little bit of everything. I do watch a lot of films—which is great for getting the voice and the general character and the atmosphere—but I tend to come up with stories that are not super-specific to particular locations.

If I’m doing Victorian London, I’m not trying to do that story for a scholar of Victorian London. In a way, I say that this is more like a 1940s film version of London—in other words, I want to do at least the level of research that you’d see in an old Hollywood film. So I’ve given myself a little distance from reality with that.

But, as I say, I do like history. If I’m doing something specific, I’ve got a ton of reference books here in the studio, and I’ll try to make sure I get some of the names right and some of the dates right, if I’m referring to specific things. But, for the most part, I tend to shy away from plotting stories that are going to require a lot of very specific, historical research.

In Witchfinder, where I’m doing Whitechapel—well, I’ve been to Whitechapel. But I’m writing about 1880s, or maybe 1870s, Whitechapel, and I want it to seem like the real thing. So I did a little bit of homework on the East End. But the trouble with doing research for this stuff is that you start finding so much material that’s interesting, after you’ve already plotted the story, and you think, oh, I want to use this, and I want to use this, and I want to use this—well, uh oh, too late.

In terms of specifics, a little bit of dialogue, a little bit of color, a little bit of flavor, will give any story a certain amount of authenticity, but I’m not looking to make giant plot points out of that kind of stuff. It’s just background. Most of my buildings, and most of the things I do stories around—when I’m drawing these things, I’m trying to create objects, buildings, ships, whatever, with a particular background. I want it to feel like there is more to the story than can be told.

But, yes, you know, I have traveled a bit—and people love to think that what I’m doing comes from lots of traveling, and from talking to old monks and that sort of thing—

BLDGBLOG: [ laughs]

Mignola: —and I have spent more time in Prague than I ever thought possible. But, other than a story I haven’t yet done—about a haunted couch—there are no experiences I’ve had that I’ve turned into stories. And the couch wasn’t haunted, you’ll be glad to hear; I think it was just infested with some kind of Eastern European insect.

For more exotic locations—like I did a story once set in Malaysia. It was entirely because I’d read a description years ago of a particular kind of Malaysian creature—a vampire—and I just knew I was going to do that story someday. But I needed pictures of Malaysia; I needed to do Malaysia research. That went back and forth for years, until, one day, I stumbled upon a book that just had really good photos of Malaysia. And that was it. It was the same with Norway: it was just a matter of some guy at a convention coming up to me with a book once that had great photos of Norway.

You know, I’m constantly looking for visual references. Story-wise, I’ve got all that stuff in my library—but I can never have enough photo references. There are still stories that are waiting to be told until I have the right references; and there are certain stories that I decided to set in a location just as an excuse for me to draw a particular place or building.

For instance, I did a story a couple of years ago called “ In the Chapel of Moloch." It was designed to take place almost entirely inside an old chapel. But the story wasn’t set in any particular location; it was just a matter of going to the books I had and looking for a building that would be fun to draw, or for a city that would be fun to draw, and I happened to have a book on Portugal. It had these great photos of decrepit hill towns, and a couple really good pictures of an old chapel. There was nothing about the story that was specific to Portugal—it was just that Portugal would be fun to draw. It was a nice, exotic location that I had never drawn before. And that's usually how it works.

[Images: From Hellboy: In the Chapel of Moloch by Mike Mignola, courtesy of Dark Horse Comics].

BLDGBLOG [Images: From Hellboy: In the Chapel of Moloch by Mike Mignola, courtesy of Dark Horse Comics].

BLDGBLOG: Stepping away from the idea of setting, I’m also interested in how you populate your stories with this constantly shifting catalog of sinister, yet natural, creatures: amphibians, frogs, worms, apes, gorillas. What is it about these particular species that works so well in terms of developing your mythological world?

Mignola: Well, I think monkeys are funny—that’s the easiest answer there. I don’t really love monkeys—but they’re kind of fun to draw. Something I always say is: monkeys always work. [ laughter] People just like to see monkeys show up in these stories. I think it’s the absurdity of it.

In one of the first issues of Hellboy, I showed a 1940s scientist. I was drawing a bunch of scientists in a room, and one guy was actually just a severed head in a jar—but that wasn’t enough. The picture needed something else. So I drew a giant gorilla towering over them, with these Frankenstein-like bolts sticking out of his neck.

Oh—and you know what? Go back even earlier than that. Go back to one of the try-out stories—one of the teaser stories—before I even started the Hellboy series. It was a Frankenstein gorilla about to stick a needle in a girl’s neck—and, not that I stole the image from pulp magazines, but it’s such an old, clichéd, pulp magazine image. Making it a Frankenstein gorilla probably took it one step further, and made it my own, but it’s just... it’s funny. It’s so absurd it’s funny.

So, yeah, I use monkeys. And monkeys are usually the animal you associate with animal-testing. For instance, there’s another story where Hellboy’s blood is being extracted—and what are you going to inject Hellboy's blood into? A rat? A rat just isn't as much fun to draw turning into a giant hell-rat—actually, that’s not a bad idea—but it would be much more fun to take a monkey and turn it into a big demon-monkey, which is what I did.

As far as frogs and other amphibian stuff—that, again, is a reference to this kind of H.P. Lovecraft worldview where anything from the ocean is scary. Frogs, in a Lovecraft sense, are associated with some kind of unknowable world. They're not from the ocean, but they're also not from, you know, the woods. Where do they come from? And why are they always out there... chirping, or whatever the hell it is that frogs do? Lovecraft also uses birds that way—and birds are great—but I have a harder time drawing birds than frogs.

In the very first issue of Hellboy, I did a sequence with frogs in it, and it just sort of stuck. I established it early. Frogs will be my kind of icon characters; when frogs show up, you know something bad’s going to happen. They become symbolic of this kind of evil that’s always running around in the background.

And then things just tend to snowball. You know, you hear about something like a “rain of frogs,” which happens periodically for whatever reason—it’s one of those weird phenomena that gets written about—and, I thought, well, let me have a little bit of that kind of action. I mean, that’s a weird thing and it’s got a kind of authenticity to it: there’s something about it that’s unnatural, yet supposedly it does really happen. And I like that.

But I think you’ve put more thought into these questions than I have into why I do these things!

[Images: Covers by Mike Mignola, from Abe Sapien: The Drowning and B.P.R.D.: War on Frogs, courtesy of Dark Horse Comics].

BLDGBLOG [Images: Covers by Mike Mignola, from Abe Sapien: The Drowning and B.P.R.D.: War on Frogs, courtesy of Dark Horse Comics].

BLDGBLOG: No, this is fascinating. It’s great to hear how you work. You mentioned H.P. Lovecraft: I’m curious to hear what you think it is about the Lovecraft universe—about the mythology of H.P. Lovecraft—that remains so appealing. In fact, it actually seems to be increasing in popularity today.

Mignola: For me, the monsters in Lovecraft are... you know, they're fine. But what’s really appealing to me is his antiquarian sensibility. It’s the old houses in Rhode Island. It’s the fact that the guys are all scholars and they’re researching things, and there are references to different editions of this book or that book, and this edition is in that library, and a Latin translation of that book is in this other library. He writes about smart guys who spend a lot of time in libraries—and I love that.

His stories are set in a time when people are still wearing suits everyday. They even have upturned collars and things like that. There’s just a wonderfully old-fashioned, scholarly antiquarian feel to the stuff. It bridges the gap between modern horror and the old, classic M.R. James ghost stories—Lovecraft just added bigger monsters. Instead of some shadowy thing that skitters along the wall, it’s a giant octopus in space that makes people go crazy.

But it’s his obsession with old buildings, and shuttered windows, and climbing into church steeples—it’s his locations. I just love that.

[Images: Covers by Mike Mignola, from Hellboy: The Storm and B.P.R.D.: King of Fear, courtesy of Dark Horse Comics].

BLDGBLOG [Images: Covers by Mike Mignola, from Hellboy: The Storm and B.P.R.D.: King of Fear, courtesy of Dark Horse Comics].

BLDGBLOG: As well as things like abandoned fishing towns in New England, with collapsing wharves and moonlit salt marshes and that sort of thing.

Mignola: That’s actually one of my dream projects: to sit around and do half a dozen paintings of those towns. To do a series of drawings that’s just called Arkham, and it’s all about these buildings in creepy old coastal towns where the walls are falling over and they have these wonderful leans.

[Images: Covers by Mike Mignola, from Hellboy: The Sleeping and the Dead and Hellboy: Double Feature of Evil, courtesy of Dark Horse Comics].

BLDGBLOG [Images: Covers by Mike Mignola, from Hellboy: The Sleeping and the Dead and Hellboy: Double Feature of Evil, courtesy of Dark Horse Comics].

BLDGBLOG: That brings us back to the idea of architecture and the role that architecture plays in your work. What brings you to draw a certain building or structure—and what do you add or exaggerate to make it more your own?

Mignola: [ laughs] Well, once upon a time, when I started all this stuff, the one thing I didn’t want to draw at all was buildings. Because, growing up in California, buildings to me were an exercise in using a ruler and perspective, and shit like that. I just had no interest in drawing that kind of stuff.

It was only after having lived in New York for a while, around really old buildings—where you see that, actually, this building’s kind of sagging and that building’s kind of leaning against the other building next door and this chimney looks like, if those three wires weren’t there, it would all fall over, and that fire escape is at some odd angle— that’s when I really started to love architecture.

It’s one of those things that is still evolving in my work, as I become more and more comfortable drawing that sort of stuff: my buildings lean more.

Right now, I’m drawing an old house, and the house is leaning one way, the fence is leaning another way; I’m working from photo references, as I love to do, but I’m able to exaggerate it, and say, yeah, okay, this building’s kind of crooked in the photo, but let’s lean it way the hell over there. Let’s throw a couple of sticks out of it this way. Let's make the building next door look like it's about to fall over. And let's make everything dark.

It’s really one of my favorite things to draw these days: old, crumbling architecture.

[Image: From “The Whittier Legacy" by Mike Mignola, courtesy of Dark Horse Comics; originally published in USA Today].

BLDGBLOG [Image: From “The Whittier Legacy" by Mike Mignola, courtesy of Dark Horse Comics; originally published in USA Today].

BLDGBLOG: Is there a particular building in your recent work that stands out this way?

Mignola: I recently did an 8-page story for USA Today called “ The Whittier Legacy.” I said I was going to keep it simple for myself; I would set it almost entirely inside a house, in the dark. The way the story’s structured, we’re not going to spend a lot of time drawing furniture, little details, and things like that; it could just be an old, derelict house.

The most work that went into that story was going through my references and finding a really good house that would be fun to draw. I happened to have a book on Victorian houses that had a lot of really good texture to them and really nice angles, with things jutting out at weird angles. With the way I use shadow, it’s really important to me to have some sort of structure where things are going to be jutting out at different angles—because you can say, okay, if I light it on this side, that bit’s going to be in shadow; but if I light it on that side, then this is going to be in shadow. A square? You get light on one side and black on the other.

But if it’s a square with other things sort of jutting at you out of the shadows, and if you put a big porch on it, and, you know, it’s a derelict place so it’s all sort of sagging the way those old places start to do—then that’s a really good day for me, being able to draw stuff like that.

• • •

Thanks to Mike Mignola for taking the time to talk—and for producing so many awesome comics. Thanks, as well, to Jim Gibbons, Jeremy Atkins, and Scott Allie at Dark Horse Comics for their help with the images. If this interview piques your interest, consider picking up some of Mignola's work for yourself.

|

|

[Image: Constructing with BeadBricks by Rizal Muslimin, courtesy of Brickstainable].

[Image: Constructing with BeadBricks by Rizal Muslimin, courtesy of Brickstainable].

[Images: BeadBricks by Rizal Muslimin, courtesy of Brickstainable].

[Images: BeadBricks by Rizal Muslimin, courtesy of Brickstainable]. [Image: Constructing with BeadBricks by Rizal Muslimin, courtesy of Brickstainable].

[Image: Constructing with BeadBricks by Rizal Muslimin, courtesy of Brickstainable]. [Image: The EcoCeramic Masonry System by Kelly Winn and Jason Vollen, courtesy of Brickstainable].

[Image: The EcoCeramic Masonry System by Kelly Winn and Jason Vollen, courtesy of Brickstainable].

[Images: The EcoCeramic Masonry System by Kelly Winn and Jason Vollen, courtesy of Brickstainable].

[Images: The EcoCeramic Masonry System by Kelly Winn and Jason Vollen, courtesy of Brickstainable].

[Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: From the forthcoming

[Image: From the forthcoming  [Images: From the forthcoming

[Images: From the forthcoming  [Images: From the forthcoming

[Images: From the forthcoming  [Images: From the forthcoming

[Images: From the forthcoming

[Images: Derelict landscapes and optical devices scaled up to the size of megastructures, by

[Images: Derelict landscapes and optical devices scaled up to the size of megastructures, by  [Images: From the forthcoming

[Images: From the forthcoming  [Image: Giovanni Fontana's 15th-century "castle of shadows," from a paper by

[Image: Giovanni Fontana's 15th-century "castle of shadows," from a paper by  [Image: "

[Image: " [Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for  [Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for  [Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for  [Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for  [Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for  [Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for  [Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for  [Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for  [Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for  [Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for  [Image: Fractalized Greek ornamental motif].

[Image: Fractalized Greek ornamental motif]. 1) The discussion series Humans, Robots and War continues at 4pm this afternoon with "

1) The discussion series Humans, Robots and War continues at 4pm this afternoon with " 6) Speaking of water, meanwhile, on April 1-2, 2011, the University of Pennsylvania will be hosting a symposium called In the Terrain of Water: "Water is everywhere before it is somewhere. It is rain before it is rivers, it soaks before it flows, it spreads before it gathers, it blurs before it clarifies. Water at these moments in the hydrological cycle is not easy to picture in maps or contain within lines. It is however to these waters that people are increasingly turning to find innovative solutions to the myriad water-related crises that catalyze politics, dynamics, and fears. Is it not time to re-invent our relationship with water—see water as not within, adjoining, serving or threatening settlement, but the ground of settlement? Could this be the basis of a new vocabulary of place, history, and ecology? And can the field of design, by virtue of its ability to articulate and re-visualize, lead in constructing this new vocabulary?" Check out their site for

6) Speaking of water, meanwhile, on April 1-2, 2011, the University of Pennsylvania will be hosting a symposium called In the Terrain of Water: "Water is everywhere before it is somewhere. It is rain before it is rivers, it soaks before it flows, it spreads before it gathers, it blurs before it clarifies. Water at these moments in the hydrological cycle is not easy to picture in maps or contain within lines. It is however to these waters that people are increasingly turning to find innovative solutions to the myriad water-related crises that catalyze politics, dynamics, and fears. Is it not time to re-invent our relationship with water—see water as not within, adjoining, serving or threatening settlement, but the ground of settlement? Could this be the basis of a new vocabulary of place, history, and ecology? And can the field of design, by virtue of its ability to articulate and re-visualize, lead in constructing this new vocabulary?" Check out their site for  [Image: The old Shoreditch Tube station is for sale; image and property info courtesy of

[Image: The old Shoreditch Tube station is for sale; image and property info courtesy of  [Image: From a cover by

[Image: From a cover by  [Image: A cover by

[Image: A cover by  [Images: (left) A cover from

[Images: (left) A cover from  [Images: Covers by

[Images: Covers by

[Images: Photos by

[Images: Photos by  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: Preview spreads from

[Images: Preview spreads from

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Images: Covers by

[Images: Covers by  [Images: Covers by

[Images: Covers by  [Images: Covers by

[Images: Covers by  [Image: From “

[Image: From “