|

|

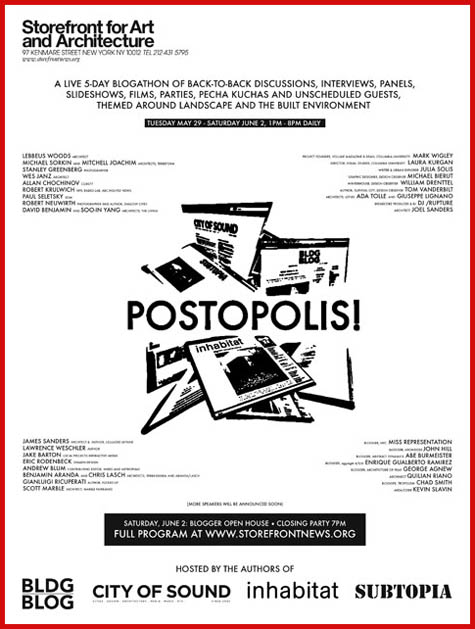

[Image: Looking through the porous facade of the Storefront for Art and Architecture]. [Image: Looking through the porous facade of the Storefront for Art and Architecture].We're into day three of Postopolis! now. If you want to learn more about what exactly it is that's going on here, Dan Hill, over at City of Sound, has been doing a bang up job keeping track of all the speakers, offering his summaries of – and commentary on – their talks. Given time over the next few days, I'll try to do my own quick version of this; there's been some fantastic stuff so far – and I think we've sorted out most of the technical issues, so there's less to worry about, and, hopefully, more time to blog. In any case, the schedule today looks like...: 1:30pm: DJ /rupture2:50pm: Gianluigi Ricuperati3:30pm: Monica Hernandez4:10pm: Jeff Byles4:50pm: Wes Janz5:30pm: Lebbeus Woods6:10pm: Robert Neuwirth6:50pm: Jake Barton7:30pm: Joel Sanders [Image: Dan Hill, live-blogging Postopolis!]. [Image: Dan Hill, live-blogging Postopolis!].So come on down. And don't miss the slowly growing Postopolis! Flickr pool for some images of the event. More soon. (Photos by Nicola Twilley).

[Image: Dan Hill and Bryan Finoki sit inside the Storefront for Art and Architecture]. [Image: Dan Hill and Bryan Finoki sit inside the Storefront for Art and Architecture].Well, day one of Postopolis! is now history – and it was a blast. We had some phenomenal presentations, from Robert Krulwich, Tobias Frere-Jones, and Stanley Greenberg; we heard from Michael Kubo, of Actar, about architectural book publishing; we managed our way through a pecha kucha featuring this blog, City of Sound, Inhabitat, and Subtopia; we drank beer; and I thought the whole thing was great.  [Image: Bryan Finoki, Jill Fehrenbacher, and Joseph Grima at the Storefront for Art and Architecture; unlike Jill and Joseph, Bryan is actually watching a baseball game...]. [Image: Bryan Finoki, Jill Fehrenbacher, and Joseph Grima at the Storefront for Art and Architecture; unlike Jill and Joseph, Bryan is actually watching a baseball game...].There are some problems with audio, on the other hand, which means that a great deal of the evening's visitors didn't actually hear anything... but we'll work on that. (If you did come out and heard nothing, I apologize!) Meanwhile, City of Sound has just posted some great action shots from the day, including a live-blogged summary of Robert Krulwich's presentation; and I've got a small Flickr set forming, and there is a Postopolis! Flickr group taking shape, as well. Today, meanwhile, Wednesday, May 30, you'll be hearing from: 1:30pm: Benjamin Aranda & Chris Lasch2:10pm: Matthew Clark4:00pm: Panel on sustainable design with Susan Szenasy, Allan Chochinov, Graham Hill, and Jill Fehrenbacher (moderated by Jill) 5:30pm: Scott Marble6:10pm: Paul Seletsky6:50pm: Ada Tolla & Giuseppe Lignano7:30pm: Michael Sorkin & Mitchell JoachimSo please come out! And say hello. Be advised, meanwhile, that Michael Sorkin might not be able to attend; we'll only know when the time comes round.   [Images: (top) Jill Fehrenbacher and Bryan Finoki watch either Geoff Manaugh or Dan Hill give a presentation; (bottom) Bryan Finoki, Joseph Grima, Geoff Manaugh, and Dan Hill set up for the day, inside the Storefront for Art and Architecture]. [Images: (top) Jill Fehrenbacher and Bryan Finoki watch either Geoff Manaugh or Dan Hill give a presentation; (bottom) Bryan Finoki, Joseph Grima, Geoff Manaugh, and Dan Hill set up for the day, inside the Storefront for Art and Architecture].And I'll keep updating everyone as the week goes on – but, for those not in NYC or who frankly don't care about Postopolis!, I'll hopefully have at least one or two new posts in the forthcoming days. (Photos by Nicola Twilley).

[Image: The Postopolis! crew: (l-r) Joseph Grima, Jill Fehrenbacher, Geoff Manaugh, Bryan Finoki, Dan Hill, and Gaia Cambiaggi (photo by Nicola Twilley)]. [Image: The Postopolis! crew: (l-r) Joseph Grima, Jill Fehrenbacher, Geoff Manaugh, Bryan Finoki, Dan Hill, and Gaia Cambiaggi (photo by Nicola Twilley)].The doors of Postopolis! burst open tomorrow. First up, at 3:00pm: Robert Krulwich3:40pm: Tobias Frere-Jones 5:00pm: Stanley Greenberg5:45pm: Michael Kubo, North American editor for Actar, discusses books, blogs, and the future of architectural publishing with Kevin Lippert, founder of Princeton Architectural Press6:45pm: Joseph Grima, Director of the Storefront for Art and Architecture, introduces BLDGBLOG, City of Sound, Inhabitat, and City of Sound, who will talk about their blogs and then lead a pecha kucha So if you're in NYC, please stop by...! And there's a lot more news coming soon.

Among many other interestings things to read in Rubble: Unearthing the History of Demolition by Jeff Byles – who will be speaking at Postopolis! on Thursday afternoon – is the fact that part of Manhattan is actually constructed from British war ruins.

[Image: Winston Churchill visits the ruins of Coventry Cathedral, 1942; courtesy of the Library of Congress]. [Image: Winston Churchill visits the ruins of Coventry Cathedral, 1942; courtesy of the Library of Congress].

Toward the end of the book, Byles describes how "[m]ore than 16 million people saw their homes wrecked by bomb destruction during World War II, with more than 4.5 million housing units completely toasted."

Further, "[w]ith London and Coventy knee-deep in rubble by the fall of 1940, a phalanx of 13,500 troops from the Royal Engineers got busy ripping down war-ravaged structures."

But what to do with all that rubble...? Byles: Around that same time, New York's FDR Drive was being constructed, which ran along the east side of Manhattan. "Much of the landfill on which it is constructed consists of the rubble of buildings destroyed during the Second World War by the Luftwaffe's blitz on London and Bristol," the historian Kenneth T. Jackson wrote. "Convoys of ships returning from Great Britain carried the broken masonry in their holds as ballast." When you're driving around on the FDR, in other words – or, for that matter, when you're simply looking out over the east side of Manhattan – you and your gaze are passing over fragments of British cathedrals and London housing stock, flagstones quarried from Yorkshire, the shattered doorframes and lintels – and eaves, and vaults, and partition walls, and bedroom floors – of whole towns, pieces of Slough and Swindon perhaps, embedded now in asphalt, constituting what would otherwise have passed for bedrock.

Down in the foundations of the city are other cities.

(Elsewhere: We learn that the British coast has become geologically French, further complicated our future sense of geological belonging – raising the interesting possibility that one can exist in a state of geological alienation... Psychoanalysts will have a field day. [via]).

I'm still reeling from the announcement of Postopolis! – but the good news keeps on coming.  To make a long story still rather long... Back in January, Alan Rapp, the art, design, and photography editor for Chronicle Books, attended a BLDGBLOG event hosted by the Center for Land Use Interpretation here in Los Angeles. Alan and I met, kept in touch, had a pizza, talked about David Cronenberg; and then, last month, we organized an event together in San Francisco. Somewhere in there the idea of a BLDGBLOG book came up – which I soon turned into a formal proposal... and now it's official: Chronicle Books will be publishing a BLDGBLOG book in Spring 2009 – and my head is spinning! BLDGBLOG: The Book! The BLDGBLOG Book!I just can't even believe how many possibilities there are with this thing. It's a little crazy. In a nutshell, though, it'll be divided up into three major sections – Architectural Conjecture, Urban Speculation, and Landscape Futures – covering everything I've already covered here and more... From plate tectonics and J.G. Ballard to geomagnetic harddrives and undiscovered Manhattan bedrooms, via offshore oil derricks, airborne utopias, wind power, fossil cities, statue disease, inflatable cathedrals, diamond mines, science fiction and the city, pedestrianization schemes, the architecture of the near-death experience, Scottish archaeology, wreck-diving, green roofs, W.G. Sebald, flooded Londons of the climate-changed future, William Burroughs, Andrew Maynard, LOT-EK, Rupert Thomson, The Aeneid, shipbreaking yards, Die Hard, Pruned, Franz Kafka, Rem Koolhaas, tunnels and sewers and bunkers and tombs, micronations, underground desert topologies, Mars, Earth, lunar urbanism, sound mirrors, James Bond, the War on Terror, earthquakes, Angkor Wat, robot-buildings and the Taj Mahal, Archigram, the Atlas Mountains, refugee camps, Walter Murch, suburbia, the Maunsell Towers... and about nine hundred thousand other topics, provided I can fit them all in. There will be interviews, essays, quotations, photos, original artwork – and hopefully even a graphic novel, strung throughout the book. And it will be well-designed and affordable! And it will put all existing architecture books to shame. Every single one of them. Except maybe a few... And, importantly, even if there's someone out there who's read every single post on this site – I know I haven't – they'll still find loads of new material.  Further, since I'll more or less be writing this thing over the next six months, I'd love it – love it! – if BLDGBLOG readers wanted to make suggestions, or send me links, or leave comments, or tell me what to avoid... In fact, half the joy of writing BLDGBLOG has always been the comments, so I hope I can even figure out a way to include the best of them in the book somehow, either chasing down anonymous readers for permission or... something, I don't know, but the whole point is to be open to everyone's input and ideas. A BLDGBLOG book Flickr pool, perhaps... Or a design contest... A questionnaire... What's your favorite bus stop in the world and why? Who knows – but this should be an absolute blast – and I'll make sure that the book is actually worth picking up. You won't just get a bunch of crap you've already read, reprinted word-for-word from the blog, served back to you for $30 (or $20, or $25...). But, man, I don't even know how many blogs make the leap into book-form! So I'm also nervous. But excited. And a little delirious with possibilities. Hoping that I do it right. So look out for BLDGBLOG: The Book, or The BLDGBLOG Book, or whatever it will eventually be be called, coming soon to a Borders near you. Spring 2009. Chronicle Books. In a deal that never would have happened had it not been for Alan Rapp. And, of course, without so many hundreds – and hundreds – of people out there, who went out of their way to help BLDGBLOG find an audience – or who just did or wrote or built or made or said something cool, thus supplying me with material – I might never have started blogging at all. So I don't want to jump into some kind of Academy Award acceptance speech here, but I really do have to say thanks to dozens and dozens and dozens of people, including, but in no way limited to – hold your breath: my wife, for editing almost literally every single post I've written on this thing and making everything, universally, on all levels, better; Javier Arbona, Bryan Finoki, John Jourden, and Paul Petrunia, in particular, of Archinect for the early break, as well as the entire Archinect crew for putting up with me there; Alex Trevi at Pruned; Marcus Trimble of gravestmor; Simon Sellars at Ballardian; Sarah Rich and Jill Fehrenbacher; Jonathan Bell of things magazine; David Maisel; Cory Doctorow, Jason Kottke, William Drenttel, Jim Coudal, Bruce Sterling, Steve Silberman, Robert Krulwich, Lawrence Weschler, Douglas Coupland, Warren Ellis; The Kircher Society; all the people I've interviewed; all the people who have participated in BLDGBLOG events; all the commenters out there, both regular and one-time only, including people who have disappeared (or who no longer leave comments – I miss you!); all the people who have sent me tips; Christopher Stack; Dan Polsby; friends of mine who were part of BLDGBLOG at the very, very beginning, before it even had a logo, including Jim Webb, Cathy Braasch Dean, Neena Verma, and Juliette Spertus; David Haskell of the Forum for Urban Design; William Fox; Ruairi Glynn, Abe Burmeister, Dan Hill, Régine Debatty, Chris Timmerman, Chad Smith, Dave Connell, John Hill, Jaime Morrison, Andrew Blum; Scott Webel; Matthew Coolidge, Sarah Simons, and Steve Rowell of the Center for Land Use Interpretation; Materials & Applications; Leah Beeferman; John Coulthart; Theo Paijmans; my del.icio.us network for linking to so many interesting things; Joerg Colberg; Siologen, Dsankt, and Michael Cook; Theresa Duncan; Curbed LA and SF; Jörg Koch; Steven Ceuppens; Yahoo!, Time Magazine, MSNBC, The Guardian, The Wall Street Journal, The Architectural Review, Mark Magazine, Artkrush, Planetizen; Thomas Y. Levin and Annette Fierro, for letting me sit-in on their classes, free, way back in 2004, leading directly to the birth of this blog; my family (including in-laws!); Blogger; and about ninety-nine million other people, things, places, friends, writers, editors, architects, and on and on and on. BLDGBLOG would have folded up and disappeared long ago were it not for the encouragement of people who it would take me literally the next two days to thank completely. So thanks – again – especially to Alan Rapp and to Chronicle Books. Meanwhile, expect to hear more about all this as I set about actually writing it... And I'll hopefully see some of you in New York City next week for Postopolis!(Note: I'll add more links and such in a little bit – including the names of people who I'll realize, with horror, that I forgot to mention).

Well, I'm off for New York City this weekend for Postopolis! – but there's a whole lot of news to announce in the meantime, including some new speakers and a relatively up-to-date schedule.  So... Since I last posted about this thing, we've added Keller Easterling, author of Enduring Innocence: Global Architecture and its Political Masquerades, in which you can read about Indonesian piracy, POW camps, hydroponic tomato farms, special economic zones, golf courses, Hindu temples, offshore wind farms, cruise ships, and other "spatial formats" of global capitalism; Jeff Byles, author of Rubble: Unearthing the History of Demolition, where we learn about "the peculiar sounds of failure" as buildings collapse, architecture turning to dust with the help of high explosives (it's a great book!); Beatriz Colomina, author of Domesticity at War, where she suggests that "postwar American architecture adapted the techniques and materials that were developed for military applications," turning domesticity into a kind of spatial appropriation of warfare; Monica Hernandez, who'll be coming in from Lifeform, a NY-based architecture firm whose work focuses on "green building, including material innovations, new technologies, and waste management issues"; Michael Kubo, the North American editor of Actar, who will be discussing blogs, books, online media, and the future of architectural publishing; Matthew Clark, an engineer at Arup; Tobias Frere-Jones, an internationally renowned typographer, discussing typography, signs, and the city; and several others, yet to be announced. We've even printed a bookmark – so you'll be saving your place in architectural texts with Postopolis! for years to come. The official schedule, meanwhile, subject to one or two last-minute changes, looks like this: 3:00pm: Robert Krulwich3:40pm: Tobias Frere-Jones5:00pm: Stanley Greenberg5:40pm: Michael Kubo6:30pm: Joseph Grima, Director of the Storefront for Art and Architecture, introduces BLDGBLOG, City of Sound, Inhabitat, and Subtopia, who will talk about their blogs, tell bad jokes, sweat through their clothes out of nervousness, then lead a pecha kucha, free and open to the public 1:30pm: Benjamin Aranda & Chris Lasch2:10pm: Matthew Clark4:00pm: Panel on sustainable design with Susan Szenasy, Allan Chochinov, Jill Fehrenbacher, and others to be announced 5:30pm: Scott Marble6:10pm: Paul Seletsky6:50pm: Ada Tolla & Giuseppe Lignano7:30pm: Michael Sorkin & Mitchell Joachim1:30pm: DJ /rupture2:50pm: Gianluigi Ricuperati3:30pm: Monica Hernandez4:10pm: Jeff Byles4:50pm: Wes Janz5:30pm: Lebbeus Woods6:10pm: Robert Neuwirth6:50pm: Jake Barton7:30pm: Joel Sanders1:30pm: Julia Solis2:10pm: Andrew Blum3:00pm: William Drenttel, Tom Vanderbilt, and Michael Bierut 4:10pm: James Sanders4:50pm: David Benjamin & Soo-in Yang5:30pm: Kevin Slavin6:10pm: Eric Rodenbeck6:50pm: Laura Kurgan7:30pm: Lawrence Weschler1:30pm: Conversations with Mark Wigley and Beatriz Colomina3:30pm: Keller Easterling4:15pm: Randi Greenberg5:00pm: Blogger open house with George Agnew, Alec Appelbaum, Abe Burmeister, John Hill, Miss Representation, Aaron Plewke, Enrique Ramirez, Quilian Riano, Chad Smith, and others to be announced 7:30pm: closing party with food, spilt drinks, and music, open to everyone  [Image: What the facade of the Storefront for Art and Architecture will look like if we get to plaster it with our logos... View larger]. [Image: What the facade of the Storefront for Art and Architecture will look like if we get to plaster it with our logos... View larger].Hopefully posts will continue to appear throughout the week – but if you're anywhere near New York in the next ten days, please come by, say hello, ask questions, stare at Bryan Finoki, use the restroom, become obsessed with architecture, give us hell for not having a single novelist in the line-up (we tried), and so on. Here's a map.

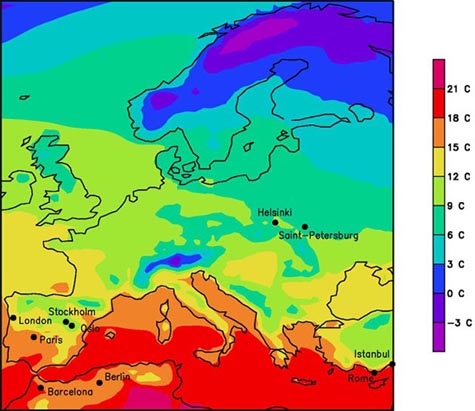

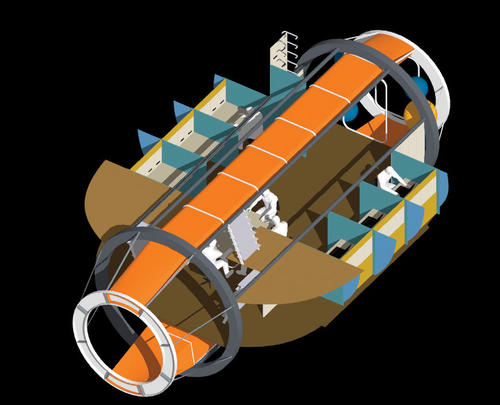

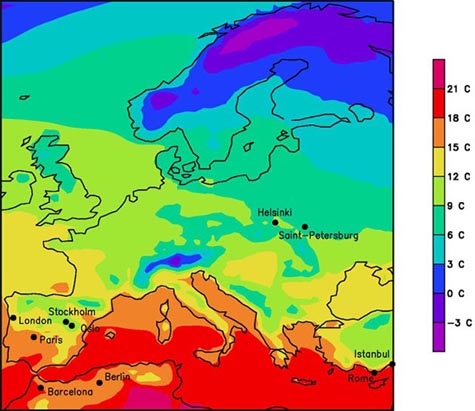

[Image: Future climate map of Europe; the cities have been relocated based on what present locations their future climate will most resemble... or something like that]. [Image: Future climate map of Europe; the cities have been relocated based on what present locations their future climate will most resemble... or something like that].Last week, the Guardian took a look at what London might look like in 2071. The city, they suggest, will be defined by "heat, dust, and water piped in from Scotland." To illustrate the point, that article includes a somewhat cryptic climate map, produced by scientists at the University of Bremen. The map relocates Europe's capital cities to the present region that most closely resembles their impending future circumstances. In other words, London, in 2071, will be more like a city on the coast of Portugal today; Paris will feel how central Spain now feels; Berlin, unbelievably, will be like north Africa (one of the coldest summers I've ever experienced was in Berlin) – and so on. These regions are those cities' "climate analogues." In any case, one of the scientists behind the map says that it's also meant to "help architects and officials who plan buildings, streets and services to adapt to the likely impacts of global warming. 'If you look at the map you see that Paris moves to the south of Spain. It's scary that just a few degrees rise will make such a difference. Paris is currently designed to deal with a very different climate, which means designs in future will have to be very different.'" For exameple: "Houses and buildings in northern Europe typically have windows to the west to make the most of meagre winter sun... 'But in warmer countries you will never find windows to the west because the sun just pours in all afternoon during the summer.'" What isn't mentioned, however, is that architecture will have to change gradually, decade by decade, even year by year; after all, it'd be inappropriate to get rid of all west-facing windows today – and it might still be premature, come 2030 – but, by 2071, perhaps all west-facing windows will be entirely phased out... Or skylights, or rain catchment systems, or winter insulation, or whatever. But you'll be able to track changes in the European climate based on what styles of architecture still exist, and where. Read more at the Guardian. (Story originally spotted at Kottke).

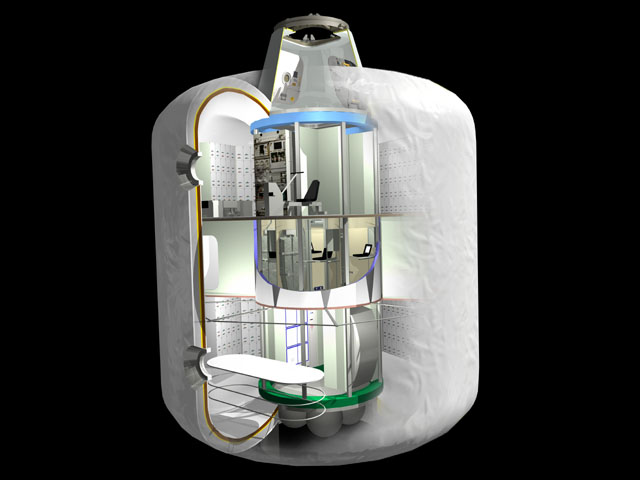

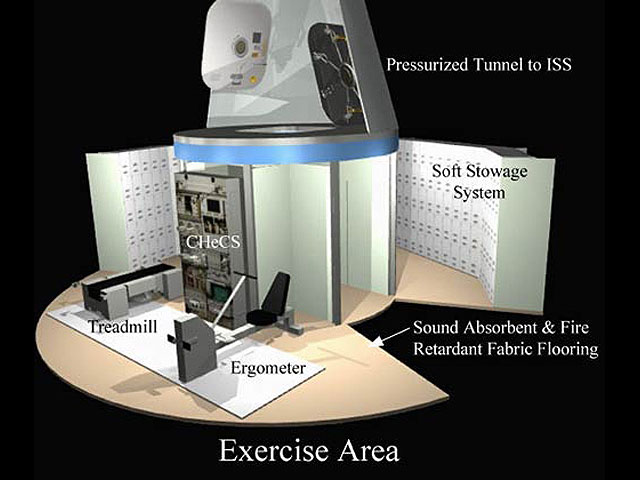

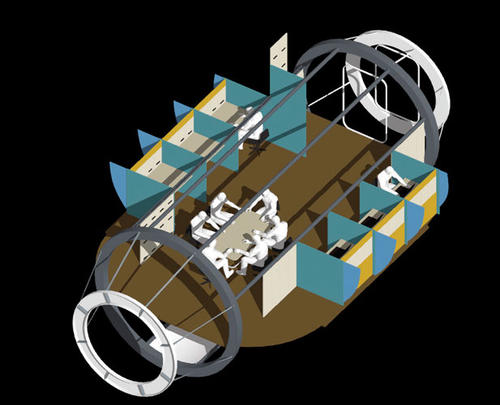

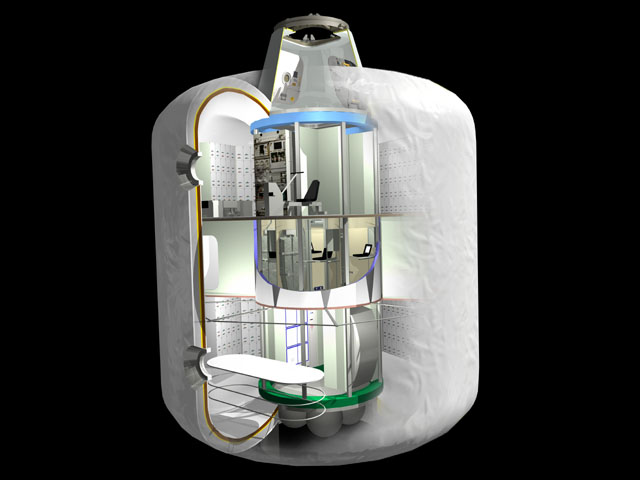

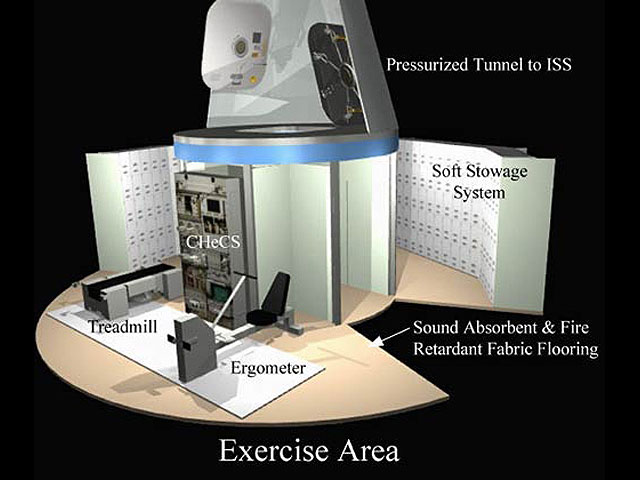

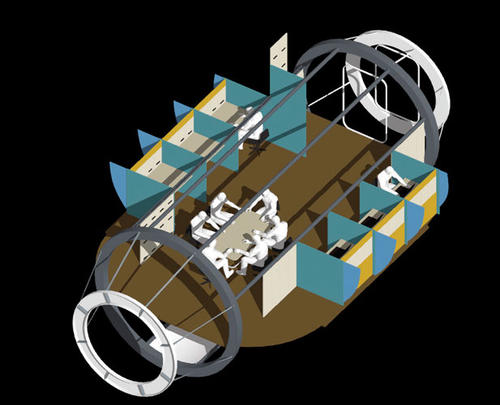

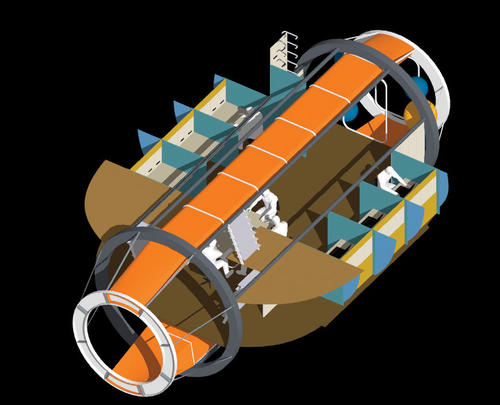

[Image: NASA's TransHab module, attached to the International Space Station. TransHab designed by Constance Adams; image found via HobbySpace]. [Image: NASA's TransHab module, attached to the International Space Station. TransHab designed by Constance Adams; image found via HobbySpace].Last week, Metropolis posted a short article by Susan Szenasy discussing a recent talk given by NASA architect Constance Adams. Adams designed the TransHab, an inflatable housing module that connects to the International Space Station. Her work, Szenasy explains, shows how architects can successfully "interface people with... interiors in space" – with strong design implications for building interiors here on Earth.  [Image: NASA's TransHab module; image via HobbySpace]. [Image: NASA's TransHab module; image via HobbySpace].As Metropolis reported way back in 1999, Adams's "path to NASA was a circuitous one. After graduating from Yale Architecture School in the early 1990s, she worked for Kenzo Tange in Tokyo and Josef Paul Kleiheus in Berlin, where she focused on large projects, from office buildings to city plans. But in 1996, when urban renewal efforts in Berlin began to slow down, she returned to the United States." That article goes on to explain how her first project for NASA was undertaken at the Johnson Space Center; there, she worked on something called a " bioplex" – a "laboratory for testing technologies that might eventually be used" on Mars, Metropolis explains. The bioplex came complete with "advanced life-support systems" for Mars-based astronauts, and it was thus Adams's job "to design their living quarters." A few years later came the TransHab module. If one is to judge from the architectural lay-out of that module, we can assume that domesticity in space will include "bathrooms, exercise areas, and sick bays," as well as "sleeping and work quarters," an "enclosed mechanical room," a few "radiation-shielding water tanks," and even a conference room with its own "Earth-viewing window."  [Image: The TransHab, cut-away to reveal the exercise room and a "pressurized tunnel" no home in space should be without. Image via Synthesis Intl. (where many more images are to be found)]. [Image: The TransHab, cut-away to reveal the exercise room and a "pressurized tunnel" no home in space should be without. Image via Synthesis Intl. (where many more images are to be found)].For more info about Adams and her architectural work, see this 1993 interview (it's a pretty cool interview, I have to say); download this MP3, which documents a conversation between Constance Adams and journalist Andrew Blum (the latter of whom will be speaking at Postopolis! next week); or click way back to BLDGBLOG's slightly strange, and now rather old, look at Adams (and many other astro-structural subjects) in Lunar urbanism 3. So I'll just end here with a few images, all of which are by Georgi Petrov, courtesy of Synthesis Intl.. According to Metropolis, these "show the different levels and spatial configurations for SEIM, a semi-inflatable vehicle created for both flight and planetary or lunar deployment." It was developed for NASA; you're looking at Level 3.    [Images: Georgi Petrov, courtesy of Synthesis Intl.].[Note: Susan Szenasy, the Editor In Chief of Metropolis magazine, will also be speaking at Postopolis! next week. Stay tuned for an up-to-date schedule]. [Images: Georgi Petrov, courtesy of Synthesis Intl.].[Note: Susan Szenasy, the Editor In Chief of Metropolis magazine, will also be speaking at Postopolis! next week. Stay tuned for an up-to-date schedule].

[Image: A green Trafalgar, via the BBC]. [Image: A green Trafalgar, via the BBC]. There's a new landscape installation in London. "More than 2,000 sq m of turf has been laid as part of Visit London's campaign to promote green spaces and villages in the city," the BBC reports today. The grass will cover the square for two days during which visitors will be able to soak up the sunshine in specially laid-out deckchairs or enjoy a picnic.

The turf, which has been sourced from the Vale of York, will then be moved to Bishops Park in Hammersmith and Fulham. Certainly not the most exciting idea in the world; but I love the underlying concepts: 1) Take a distant landscape (something "sourced from the Vale of York," for instance) and install it in the center of London. This gives rise to all sorts of possibilities – like recreating the Brecon Beacons throughout the streets of Westminster (you do it in the dead of night and don't tell anyone what you're doing). Or: 2) You swap landscapes, installing Trafalgar Square somewhere in the Vale of York to promote urban spaces and cities in the local farmland. Then again: 3) You simply install lawns everywhere: inside movie theaters and churches and airplanes and hot air balloons... Airborne landscapes and gardens! Flying yards. You then form a company, incorporated in Maryland, called, yes, the Flying Yards and you perform distant landscapes in the sky for stunned crowds. 4) You transform London into what it will look like after it's been taken over by wild grasses and tree roots and weeds – perhaps even fencing off whole parts of Camden for several years as a complicated work of land art: the city gone feral. Someone at Goldsmiths writes a PhD about you... But more soon on such future visions of a new London to come.

During an event the other night, I had a brief olfactory encounter with a waterless urinal. While I know that waterless urinals are environmentally fantastic – they save literally tens of thousands of gallons of water a year – I also think that they can smell extraordinarily bad. The instant you put one to use, in other words, you're made instantly aware of all the people who have been there before. In fact, the experience made me wonder if you could prevent burglary by making houses smell like that: no one, not even a burglar, would come near.  If you could make your house smell like urine, in other words, all your possessions would be permanently safe... So I was thinking, specifically, that you should attach some kind of scent-emission device to your home burglar alarm – or above the windows and beside the front doorway – before you go away for the weekend. You then just have to choose what scent will be emitted; you type in your PIN; and you go. Because then, if someone actually does break into your house... an invisible puff of scented air – a defense cloud™ – goes misting out into the hallway, settling down onto your erstwhile burglar – who thus finds himself greeted with an alarmingly strong scent of urine. The scent gets worse by the minute, and seems to be coming from all sides. What is this place...? the burglar thinks. Do they manufacture waterless urinals here? He recoils in horror. But should the determined home invader persist in his folly, the scent-alarm simply kicks it up a notch, through different aromas, making everything that much worse – moldy potatoes, rotten chicken parts, gangrenous limbs and human corpses – till only someone without a nose, or a true sociopath, could even contemplate sticking around. In which case your scent-alarm phones the police. Only a few unfortunate customers have reported product malfunction. A scented car alarm is now in development.

[Image: The final night of the architecture and film festival. From left-right, top-bottom: the wind tunnel entrance; the set-up; the intro, by Jenna Didier of M&A; and a scene from At Rest: The Body in Architecture by Michael and Alan Fleming. Photos by Nicola Twilley]. [Image: The final night of the architecture and film festival. From left-right, top-bottom: the wind tunnel entrance; the set-up; the intro, by Jenna Didier of M&A; and a scene from At Rest: The Body in Architecture by Michael and Alan Fleming. Photos by Nicola Twilley].Thanks to everyone who came out last night for the final night of the film fest; it was a bit intimate – but it was still fun, and we made it through two cases of beer, so... you can't beat that. Anyway, I owe a huge thanks to Leslie Marcus of the Art Center College of Design for her patience, interest, and organizational help; Oliver Hess and Jenna Didier of Materials & Applications, for inviting me to help put all this together in the first place; Architecture Tours LA and Michael Maltzan Architects, our sponsors for last night's show; and to all the filmmakers who took part – and the people who came out to see their work. And hopefully we'll see you again next year!

[Image: A scene from Peter Kidger's The Berlin Infection, produced as part of Kidger's work with the Bartlett School of Architecture's Unit 15 in London]. [Image: A scene from Peter Kidger's The Berlin Infection, produced as part of Kidger's work with the Bartlett School of Architecture's Unit 15 in London].This year's architectural film fest, jointly organized by BLDGBLOG and Materials & Applications, concludes tomorrow night, Tuesday, May 22, in the wind tunnel at Pasadena's Art Center College of Design. Wired liked the first event – so hopefully we can keep the good energy flowing...  [Image: Outside the wind tunnel – a building rehabbed by Daly Genik. More info about it here]. [Image: Outside the wind tunnel – a building rehabbed by Daly Genik. More info about it here].This time round, we'll be screening something like an hour and forty minutes' worth of films, beginning at 8pm. No tickets or reservations are required – and the wind tunnel can be found here (950 South Raymond Avenue, in Pasadena). There's even free valet parking. And it should be fun: we've got some awesome films lined up – with running times coming in anywhere between two minutes and half an hour – and I'm really looking forward to this. You'll be seeing, in this or another order: Vancouverism in Vancouver, Robin Anderson and Julie Bogdanowicz Glen Festival School, Fernando Iribarren, Ayers Saint Gross (2007) LaSubterranea, Raimund McClain and Jesse Vogler (2006) At Rest: The Body in Architecture, Michael and Alan Fleming (2007) Spiral Bridge, Dennis Dollens (2007) Vert-ual, Adam and Nathan Freise (2005) Alternate Ending, David Fenster, Field Office Films (2007) London After the Rain, Ben Olszyna-Marzys (2007) The Berlin Infection, Peter Kidger (2006) Matched Pair, Bradford Watson (2004) Declarations of Love, Andre Blas (2006) Wax On/Wax Off, Benjamin Smith and Wilhelm Christensen (2006) So come on down – and say hello and drink a coffee (there's no cafe on site, however) and have a cool Tuesday night, hanging out in a wind tunnel, watching movies about architecture... And if you get restless, you can always walk around and explore Open House: Architecture and Technology for Intelligent Living, which is simultaneously on display in the exact same space. Hope to see you there!

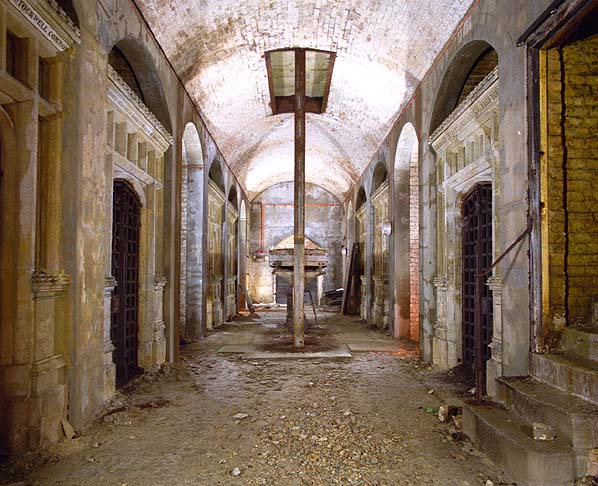

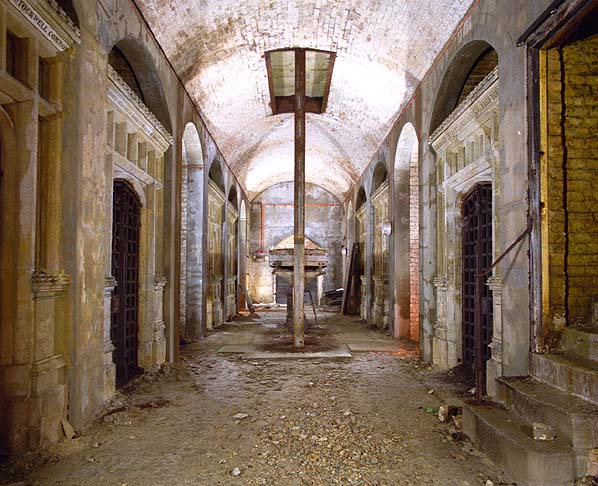

[Image: An underground "coffin lift or 'catafalque'," from London's West Norwood cemetery catacombs. "The blocked aperture in the ceiling led to the now demolished Episcopal Chapel above. The stairs on the right (now blocked) also led up to the chapel." Photo by Nick Catford, the wildly great and seemingly omnipresent photographer behind Subterranea Britannica]. [Image: An underground "coffin lift or 'catafalque'," from London's West Norwood cemetery catacombs. "The blocked aperture in the ceiling led to the now demolished Episcopal Chapel above. The stairs on the right (now blocked) also led up to the chapel." Photo by Nick Catford, the wildly great and seemingly omnipresent photographer behind Subterranea Britannica]. London's West Norwood cemetery opened to the public in 1837; it boasted "two chapels with a series of vaults or catacombs constructed beneath the Episcopal Chapel." Fantastically, the catacombs came with "a hydraulic coffin lift or catafalque to transport the coffins from the chapel to the vaults below." Although "[b]oth chapels were severely damaged during the war and the Episcopal Chapel was finally demolished in 1955 and replaced by a walled rose garden, the catacombs below were undamaged and remain intact and accessible today." A lot more information is available at Subterranea Britannica, but, if you don't feel like reading text, be sure to check out Nick Catford's photo gallery. Some of those images are genuinely creepy; some quite beautiful; others just really, really cool.

[Images: Photos by Neil Burns capture the destruction; via the BBC]. [Images: Photos by Neil Burns capture the destruction; via the BBC].The BBC posted a short photo-spread today that looks at the implosion of four cooling towers at the Chapelcross nuclear power station, in Scotland, where the UK used to produce weapons-grade plutonium. "The towers were brought down in 10 seconds, generating an estimated 25,000 tonnes of rubble," we read.   [Images: Photos by Andrew Turner and John Smith; via the BBC]. [Images: Photos by Andrew Turner and John Smith; via the BBC].I think it's interesting, though, that the towers seem to crimp and torque in some of these pictures, almost whirling, or folding, down onto themselves like some kind of self-imploding Richard Serra sculpture, made of lead-reinforced concrete. Might demolition somehow reveal other geometries and architectural forms – otherwise unknown material tendencies held at bay by engineering?  [Images: Via The Scotsman]. [Images: Via The Scotsman].In loosely related news, meanwhile, I'm excited to announce that Jeff Byles, author of Rubble: Unearthing the History of Demolition, will now be speaking at Postopolis! next week – so if you've got a soft spot for demolition, and the various arguments surrounding it, please stop by! More speakers to be announced shortly, including an up-to-date schedule.

A friend of mine once told me about the "typical dream of a New Yorker," as he described it, wherein a homeowner pushes aside some coats and sweaters in the upstairs closet... only to reveal a door, and, behind that, another room, and, beyond that, perhaps even a whole new wing secretly attached to the back of the house... Always fantasizing about having more space in Manhattan.  And so I was thinking today that you could go around Manhattan with a microphone, asking people who have had that dream to describe it, recording all this, live, for the radio – or you ask people who have never had that dream simply to ad lib about what it might be like to discover another room, and you ask them to think about what kind of room they would most like to discover, tucked away inside a closet somewhere in their apartment. What additions to space do the people of New York secretly long for? Of course, you'd probably need to record about 5000 people to get a dozen or so good stories – but then you'd edit it all down and listen to the unbelievable variations: people who find secret attics, or secret basements, secret closets inside closets, or even secret children's bedrooms, secret bathrooms, hidden roof gardens, even a brand new 4-car garage plus screened-in porch out back. One guy finds a sauna, and a cheese cave, and then a bicycle-repair shop... What does it all mean?And if you once dreamed about finding a secret UPS loading dock attached to your back door... would Freud approve? So you get all these stories together and you make a radio piece out of it. A month or two later, it's broadcast during rush hour, on a Friday night, as you want to give people something to think about over the weekend. But soon commuters are pulling over to the side of the road and staring, shocked, at the radio – because you've given no introduction, and no one out there has any idea what this is. Some guy found a boathouse attached to his apartment in Manhattan...?, one driver thinks. And the stories keep coming. There's a skyscraper with a whole hidden floor...? someone thinks, momentarily amazed – before driving into the car in front of her. A woman on the Upper East Side found what ? Or: All along he had a basketball court behind the bedroom wall? The NJ turnpike gets backed up for miles and the Brooklyn Bridge is at a stand-still. It's mass hysteria. Where are all these secret rooms...? People want to know. And why don't I have one...? Manhattanites are knocking on walls, taking measurements. drafting letters to the rent control board. But then the credits roll, and the radio station cuts to commercial, and everyone realizes that those were all just stories. Dreams. There are no secret rooms – they think. So they pull back onto the highways – and you go down in radio history. Within two weeks you've signed a six-figure deal with Henry Holt to turn it into a book, and Paul Auster volunteers to write the forward. You call it: The Undiscovered Bedrooms of Manhattan. It gets accidentally shelved with Erotica. People cry as they read it. A sequel is planned, interviewing residents of London and Beijing. (With thanks to Robert Krulwich, who puts up with emails from me full of ideas like this...).

New Scientist reports that certain architectural hallucinations associated with near-death experiences – such as bright lights at the end of long hallways and tunnels – might actually be the product of a sleep disorder.  [Image: From the series Tunnel Vision, by Jill Fehrenbacher]. [Image: From the series Tunnel Vision, by Jill Fehrenbacher].Neurophysiologist Kevin Nelson, New Scientist tells us, thinks that near-death experiences (or NDEs) "may be little more than dream-like states brought on by stress and a predisposition to a common kind of sleep disorder. If he's right, as many as 40 per cent of us could be primed to see the light." But what I think deserves more exploration is the tunnel – the architectural space within which NDEs seem to occur. For instance, is there a particular type of structure that people see when it comes to almost dying? If so, are those structures simply optical phenomena – or are there cultural and historical influences at work? If you're an architect, are your NDEs particularly detailed? And what if you see a bright tunnel, inverted, ending in a space of pure darkness...? The article doesn't really address these issues.  [Image: From the series Tunnel Vision, by Jill Fehrenbacher]. [Image: From the series Tunnel Vision, by Jill Fehrenbacher]."Written accounts of NDEs go back more than two thousand years," we learn instead, and they "have been reported all over the world. Most include a 'point of no return' that if crossed will lead to death, and a person who turns you away from it." But what about the archtecture? Does everyone see the same hallway – or do some people see large rooms, or skylights, or even underground car parks, or caves, or maybe some huge mechanical garage door that slowly creeps open...? Is there an architecture of death? Can it be measured and taught to others?  [Image: From the series Tunnel Vision, by Jill Fehrenbacher]. [Image: From the series Tunnel Vision, by Jill Fehrenbacher].If death does have a structure – or, at least, if near-death experiences do spatialize in certain pre-existing ways – if death has a spatial format, you could say – then clearly death could also be architecturally reconstructed, based on eyewitness accounts, here on earth, in the present moment, with us. We could visit it, in groups, and emotionally prepare... So what would happen if an architect teamed up with an anthropologist (who studies cultural narrations of the near-death experience) and with a neurophysiologist (who understands the underlying cortical mechanisms), to design themed environments specifically meant for triggering NDEs? It'd be a kind of post-Buddhist thanatological fun ride, complete with people passing out – then waking up, blinking and vibrant, determined to change their lives, giving hugs to others and starting things over again. Hallways of Rebirth, they might be called – and the first person to make it to the end of that hall without passing out wins $10,000.  [Image: From the series Tunnel Vision, by Jill Fehrenbacher]. [Image: From the series Tunnel Vision, by Jill Fehrenbacher].It's harder than it sounds. (All photos from Jill Fehrenbacher's Tunnel Vision series).

According to the BBC, Indian officials have concluded that a " deep-cleansing mud pack may be the only way to return a yellowing Taj Mahal to the cultural landmark's former white marble glory." By "caking the building in clay," we read, those same officials can actually "draw out surface impurities" – but how do they know whether or not they've purchased the right mud mask...? [Earlier on BLDGBLOG: the oddly popular Hurling Taj Mahals into the Sky].

A poster for Postopolis! will be coming out soon (without a red border), including the list of speakers as it now stands – and I'm unbelievably excited about this thing. I really can't wait. So: scattered over the course of five days, from May 29 to June 2, from 1pm-8pm everyday, at the Storefront for Art and Architecture in New York City, you'll be hearing from, among many others yet to be announced: Lebbeus Woods, Laura Kurgan, Michael Sorkin & Mitchell Joachim, Stanley Greenberg, Joel Sanders, Susan Szenasy, DJ /rupture, Andrew Blum, Jake Barton, William Drenttel, Tom Vanderbilt, Michael Bierut, Lawrence Weschler, Robert Krulwich, Benjamin Aranda & Chris Lasch, Randi Greenberg, Allan Chochinov, Julia Solis, Ada Tolla & Giuseppe Lignano, Scott Marble, Paul Seletsky, Robert Neuwirth, Wes Janz, James Sanders, Eric Rodenbeck, Kevin Slavin, Gianluigi Ricuperati, Quilian Riano, Miss Representation, Enrique Gualberto Ramirez, George Agnew, Chad Smith, Abe Burmeister, John Hill... and a lot more to come (including unannounced guests who just happen to be in New York that week). So it should be a blast. Stay tuned for specific times and so on, coming soon – and if you're anywhere near NY, please consider stopping by: it's not an academic conference, and the more people the merrier... Finally, the other three blogs involved in planning all this are City of Sound, Inhabitat, and Subtopia – with the indispensible help of Joseph Grima, from the Storefront for Art and Architecture.

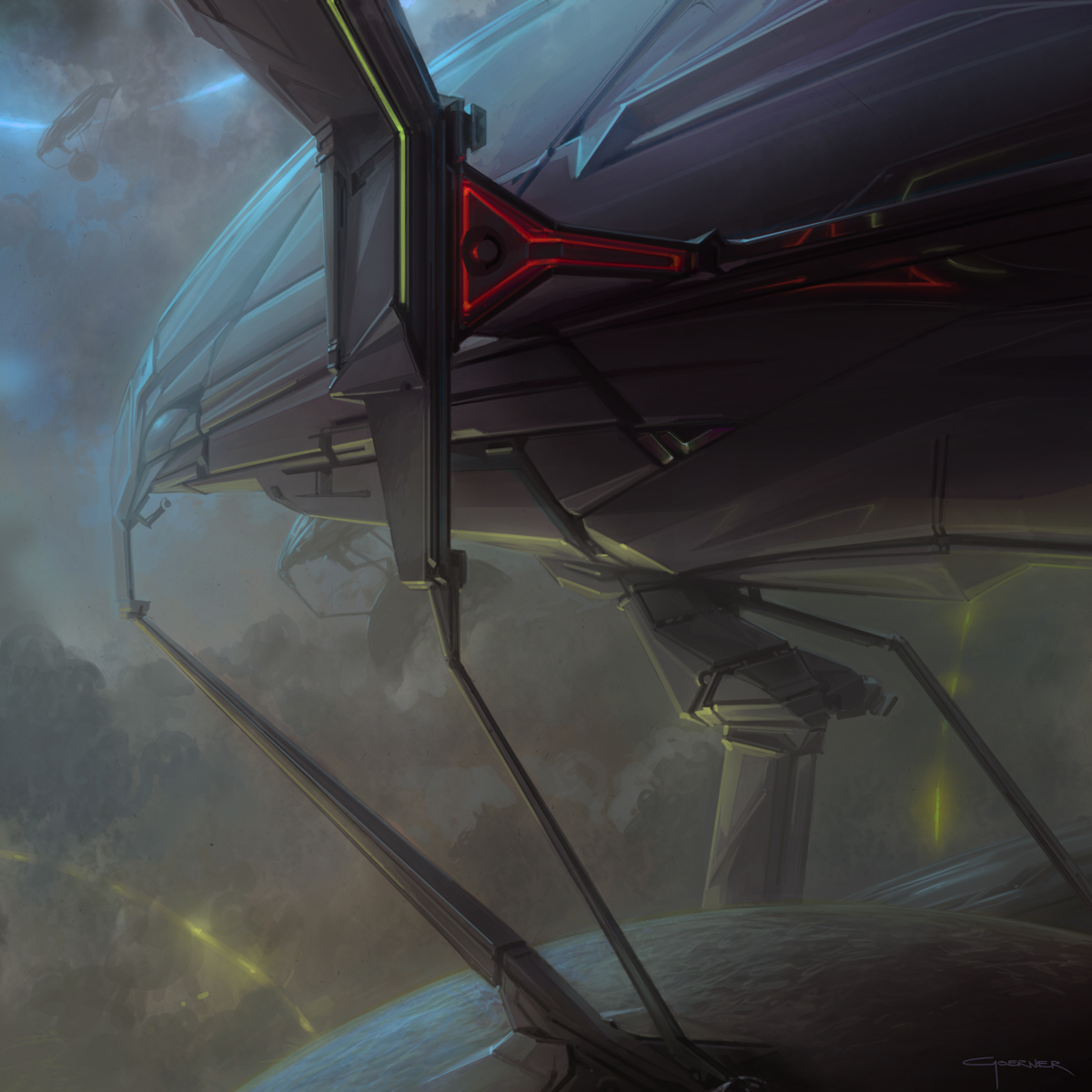

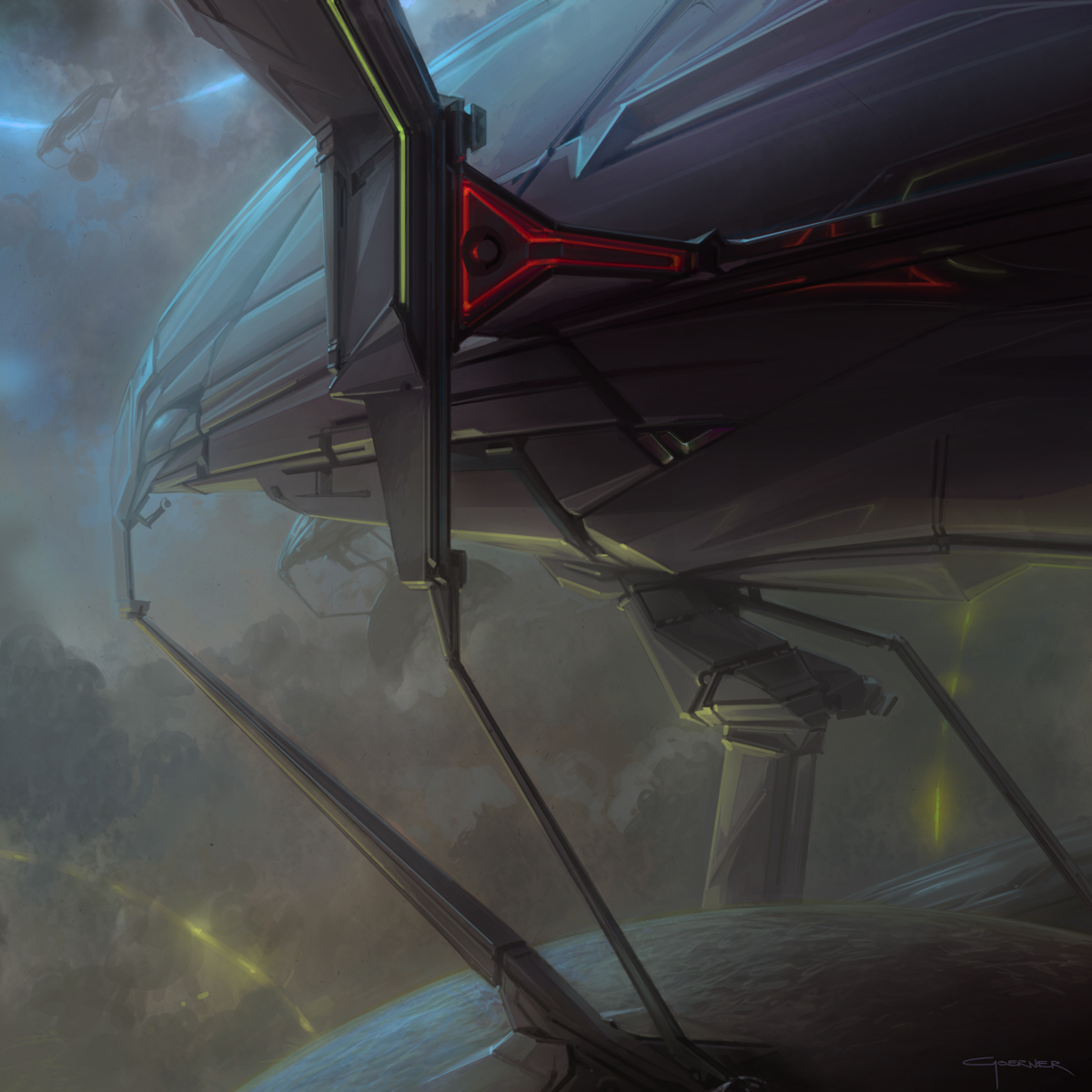

So it looks like Wired liked our science fiction and film panel, held last week.  [Image: Courtesy of Mark Goerner – here's a large version]. [Image: Courtesy of Mark Goerner – here's a large version].The four panelists, Wired writes, showed "art that's rarely seen outside the film studio: pictures of otherworldy and futuristic cities that special effects crews and CGI geeks use as blueprints to build the backdrops for outer-space fights, alien worlds and castles fit for dragons." Read more – and see a lot more images – at Wired. Meanwhile, some more background on the event can be found here, on BLDGBLOG – or you can even check out ARCHITECT Magazine's coverage of the event (although, if you read that article, note that the date for our second screening has been moved from May 9 to May 22). Finally, if you were there, thanks again for coming out!

While researching another post I hope to write soon, about Franz Kafka and a small room in San Francisco, I stumbled upon something else that seemed worth putting up on the blog; it's from Kafka's Diaries: 1910-1923. In an early entry, from 1911, Kafka describes the "unhappiness of the bachelor," an unhappiness that, for him, seems less dependent on loneliness or personal abandonment – or even on some catastrophic sense of being overlooked by the world, always – than on space: a bachelor never has enough of it.  A bachelor is alone, after all, which means that "so much the smaller a space is considered sufficient for him." One could perhaps say that, for Kafka, a bachelor is never spatially respected... In any case, looking for space – or for the proper space, the one that feels right and "has a few panes of glass between itself and the night" – our bachelor finds that he "moves incessantly, but with predictable regularity, from one apartment to another." This goes on – and on – for the rest of his isolated existence until "he, this bachelor, still in the midst of life, apparently of his own free will resigns himself to an ever smaller space, and when he dies the coffin is exactly right for him."

[Image: Ruins of the City Walls (1625-1627) by Bartholomeus Breenbergh]. [Image: Ruins of the City Walls (1625-1627) by Bartholomeus Breenbergh].In The Destruction of Memory: Architecture at War, Robert Bevan describes, in almost numbing detail, how specific buildings – indeed, whole cities – have been targeted, damaged, or otherwise destroyed by war. He writes of the "violent destruction of buildings for other than pragmatic reasons," claiming that "there has always been [a] war against architecture." This war is fought through the deliberate "eradication" of an enemy's built environment – that is, "the active and often systematic destruction of particular building types or architectural traditions." Some of Bevan's examples, however, sound less like warfare than a kind of highly complex – and extremely violent – architectural ritual, played out over centuries between rival governments and religions. This is the "repeated demolition or adaptation of each other's buildings," and retaliation can sometimes take generations. For instance, Bevan writes about the site of the cathedral, in Córdoba, Spain, which "started out as a Roman temple" before being destroyed by Christian Visigoths: A subsequent church on the site was replaced by a mosque following the Arab conquest of the early eighth century. Some seventy years later this was itself demolished to create the first stage of a massive new mosque. The Christian recaptured Córdoba in 1236 and consecrated the building as a cathedral. (...) It is said that the mosque's lamps were melted down to make new bells for the cathedral of Santiago de Compostela, 800 km to the north. This probably seemed only fair, since the lamps had themselves been made from Santiago's original bells: when the Moors had conquered the city in 997 they had dragged the bells to Córdoba and melted them down into lamps. Tit for tat. Bevan also describes how the Bastille, having been stormed in 1789, was reduced to a heap of stones – but these stones were then "broken up and sold as souvenirs," in a "commodification process repeated with the fragments of the Berlin Wall 200 years later." In any case, Bevan goes on to discuss mosques bulldozed in the Balkans, synagogues burnt to the ground in both Poland and Germany, Armenian monasteries reduced to foundation stones as, even today, they are dismantled and reused to build houses in eastern Turkey, the dynamiting of Loyalist mansions by Irish Republican militias, the destruction of the World Trade Center, and even archaeological sites fatally disturbed during the invasion of Iraq – among many, many other such examples, all found throughout Bevan's book. These are all, he says, "crimes against architecture."  More to the point here, when Bevan points out that "the bulldozed remains of the Aladza mosque" were "dumped" by Serbian troops into a nearby river – the ruins were only "identified by the mosque's distinctive stone columns" – it occurred to me that fragments like these must be numerous enough that you could use them to reassemble complete buildings elsewhere. You could construct a whole city from fragments of buildings destroyed by war.  For instance, all the gravel, dirt, and foundation stones from ruined buildings and cities around the world could be dropped into shallow waters off the western coast of Greece – forming the base of an artificial island, as large as Manhattan, on which to build your memorial to cities and spaces killed by war... You draw up plans with a local architecture school, plotting a whole new island metropolis constructed from nothing but pre-existing pieces of annihilated architecture – fitting arches with arches and floors with floors. Within a decade you've covered the island in a maze of Chicago tenement housing, Russian churches, Indian temples, and Chinese hutongs; there are Aztec walls and pillars standing inside reconstructed Romanian state houses – before most of pre-WWII Europe begins to appear, together with shattered castles, north African villages, and the weathered masonry of pre-Columbian South America, all the buildings merging one into one another, indistinct, with Mayan rocks and Kurdish roofing joined together atop bricks from Köln and Dresden. Another decade later and the island-city is complete. There are no cars and no electricity – in fact, no one lives there at all. It sits alone in the waters, covered in wild herbs and home to songbirds, casting shadows on itself, eroding a bit in the occasional rainstorm. Documentaries about it soon appear on CNN and the BBC. Only 10 people are allowed on the island at any given time; most of them just take photographs or make sketches, or write letters to loved ones, as they wander, awe-struck, through the narrow streets of this barely remembered desolation, stumbling upon extinct building types and lost statuary – towers of churches destroyed by bombs – hardly even able to conceive how all these places could have been destroyed by human conflict. They then brush the dust of structures off their shoes as they board the boat to go home, silent, looking back at this island, the sun setting a brilliant orange behind its almost pitch-black silhouette.

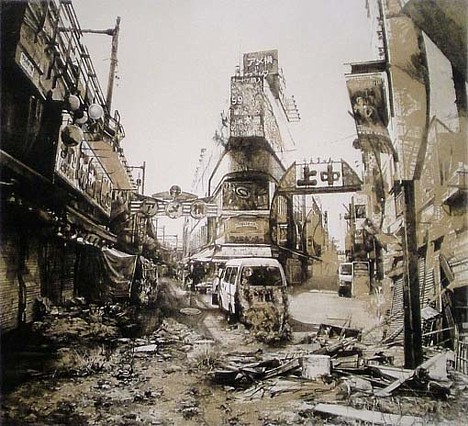

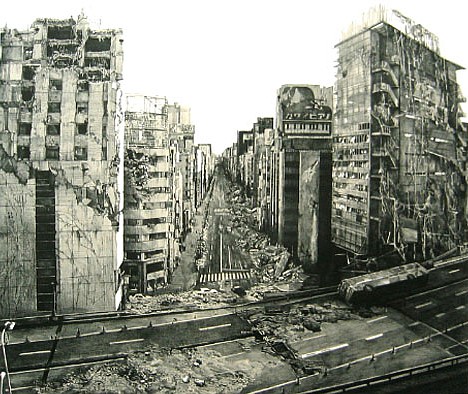

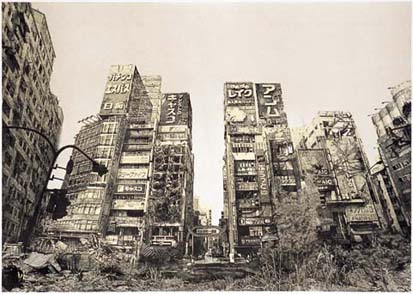

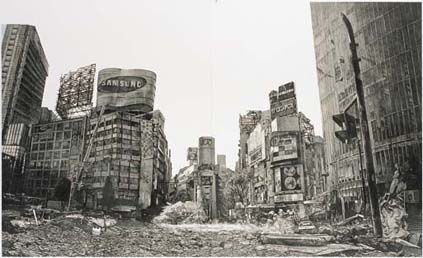

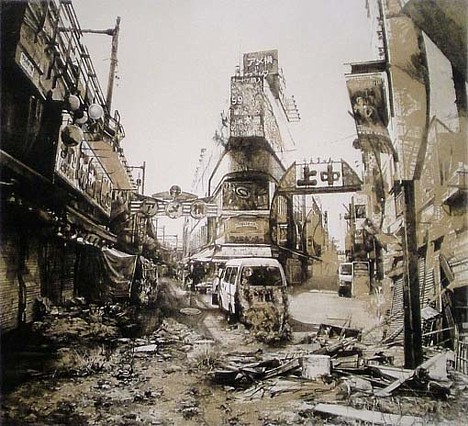

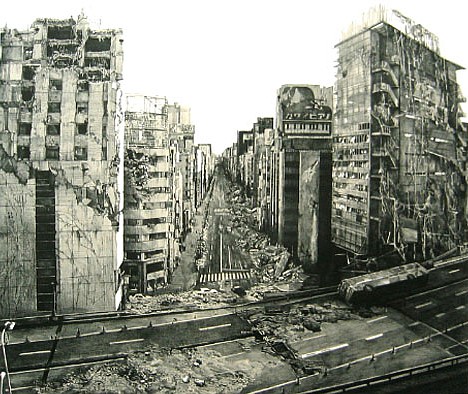

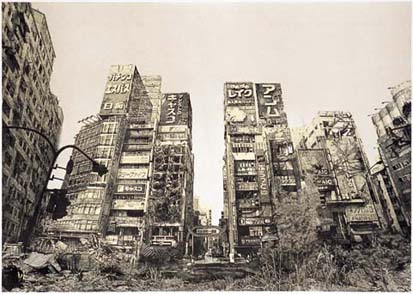

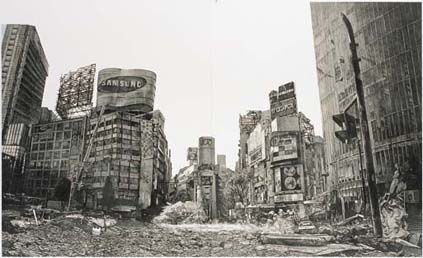

[Image: Ameyoko by Hisaharu Motoda; via Pink Tentacle]. [Image: Ameyoko by Hisaharu Motoda; via Pink Tentacle].On Wired today, we read that "Japanese photographer Hisaharu Motada [sic] envisions the radioactive and decomposing cityscapes of post-apocalyptic Tokyo in his Neo-Ruins series of photographs."  [Image: Ginza Chuo Dori by Hisaharu Motoda; via Pink Tentacle]. [Image: Ginza Chuo Dori by Hisaharu Motoda; via Pink Tentacle].From Motoda's own website: In his Neo-Ruins series Motoda depicts a post-apocalyptic Tokyo, where familiar landscapes in the central districts of Ginza, Shibuya, and Asakusa are reduced to ruins and the streets eerily devoid of humans. The weeds that have sprouted from the fissures in the ground seem to be the only living organisms. "In Neo-Ruins I wanted to capture both a sense of the world's past and of the world's future," he explains. The resulting images are actually lithographs, heavily textured, like aged prints.    [Images: Kabukicho, Shibuya Center Town, and Electric City by Hisaharu Motoda]. [Images: Kabukicho, Shibuya Center Town, and Electric City by Hisaharu Motoda].Of course, Motoda's website hosts a number of other works, including this awesome image of Hashima, or Gunkanjima Island, the wonderfully creepy abandoned former mining island off the coast of Japan.  [Image: Hashima by Hisaharu Motoda]. [Image: Hashima by Hisaharu Motoda].So who's up for making lithographs of a post-apocalyptic Cairo...? Or Chicago, or Mumbai? I'll write the wall-text. (Also found via Pink Tentacle).

The event last night was a blast, and so I want to thank everyone for coming out, especially the four panelists, Ryan Church, James Clyne, Mark Goerner, and Ben Procter; but I also want to thank Leslie Marcus, from the Art Center College of Design; Kyle Maynard, for his technical assistance; my wife, for photographing the whole thing; Scott Robertson, for putting me in touch with the panelists in the first place; and Jenna Didier & Oliver Hess of Materials & Applications, for helping put this whole event together.  [Images: The event, photographed by Nicola Twilley. From left to right, top to bottom, you're seeing the Wind Tunnel itself; BLDGBLOG introducing the speakers; Mark Goerner and James Clyne; the audience; Ben Procter; some of Ben's concept art for Superman Returns; Ryan Church, Mark Goerner, and James Clyne; Ben Procter presenting while Ryan Chuch looks on (two images); and Ryan Church presenting some of his concept art for Star Wars II: Attack of the Clones, with Ben Procter and Mark Goerner visible either side]. [Images: The event, photographed by Nicola Twilley. From left to right, top to bottom, you're seeing the Wind Tunnel itself; BLDGBLOG introducing the speakers; Mark Goerner and James Clyne; the audience; Ben Procter; some of Ben's concept art for Superman Returns; Ryan Church, Mark Goerner, and James Clyne; Ben Procter presenting while Ryan Chuch looks on (two images); and Ryan Church presenting some of his concept art for Star Wars II: Attack of the Clones, with Ben Procter and Mark Goerner visible either side].There were some slips here and there – including nearly ten seconds of awesomely explosive feedback that put Merzbow to shame – and the Q&A period at the end barely got off the ground before we had to move on to screening the films; but I was really excited to see a full house – Wired magazine was even there – and to get a look at so many truly awesome works of concept art, from impossible structures and fantasy buildings to hybridized cities and a planet made from bridges – not to mention surreal juxtapositions of Czech cubism, military aerodynamism, automotive design, origami, Hieronymous Bosch, High Gothic machine-towers, and "what the Roman empire would have looked like if it had had structural steel." It was also great just to meet the panelists themselves, finally, and to have contributed at least a tiny bit to the beginnings of a much larger conversation about film, science fiction, and architecture. With any luck, then, there will be another event of the same nature soon – or possibly a web feature here on BLDGBLOG – so we can continue what we started: to look at more of this stuff, and to ask these guys more questions, and maybe even to find out what it means that architecture students, for instance, know all about Archigram and Piranesi and the Pamphlet Architecture series, and they know all about paper architects from Boullée to Lebbeus Woods, but so many genuinely exciting architectural ideas – from science fiction films and the background of Hollywood blockbusters – are only casually, if ever, discussed. As it is, the canon of accepted architectural history excludes this stuff – for no real reason. Unless it's Metropolis or maybe Jacques Tati. But architects should be watching Minority Report as much as they read Charles Jencks or even Rem Koolhaas. In any case, I thought the event was fun, though I apologize for the wild bursts of feedback and for the 5-minute delay in starting – but I'm glad you came out, if you did, and I hope you had a good time. And if you found the conversation cut too short at the end – as I did – then feel free to say what you wished had been said at the time, here in the comments. Otherwise, watch out for a follow-up event/interview/feature at some point this summer. Finally, thanks to the filmmakers who we featured last night. If you liked Bradford Watson's 2x4x96, in particular, here's more information, including how to contact Bradford himself; and if my description of Thorsten Fleisch's movie using crystals grown directly on film – or geology turned into cinema – here it is. Next up: May 22nd, 8-10pm, in the same converted Wind Tunnel in Pasadena, nearly two hours' worth of short films about architecture, also brought to you by BLDGBLOG and Materials & Applications... Stay tuned.

More information More information about the event and a gigantic version of this poster are both available... No RSVP is required; street parking should be ample; the building looks like this; it can be found here; 8:00pm is the starting point; and, if you show up, you'll hear concept artists Ryan Church, James Clyne, Mark Goerner, and Ben Procter all discussing film, space, science fiction, and architecture. The films will be screened at the end. Hope to see you there! Meanwhile, a second night, entirely devoted to films about architecture, landscape, and the city, is still to come – once that date is finalized, we'll have another announcement. (Image in poster by James Clyne; for more images, by all four artists, don't miss the film fest Flickr page).

[Image: A street in Central Park, via Wikipedia]. [Image: A street in Central Park, via Wikipedia].I went to an event the other night about " great streets," held in a small theater on Venice Boulevard, in Los Angeles, about six blocks from my apartment. I walked there. The point of the event was apparently: 1) To discuss the importance of greening the public realm... to make our communities inherently more walkable

2) To identify the most effective methods for funding these projects

3) To better understand the bureaucratic obstacles to creating more environmentally sustainable streets & sidewalks There was also a fourth purpose: to figure out how urban space can accomodate "bikes, cars, pedestrians, flora & fauna, watershed management, open space, street vendors, retail, recreation & relaxation, [and] transit." All of which sounds like a great event to me, with an awesome purpose, coming at an interesting time for urban planning; but the conversation almost immediately turned into something far stranger and infinitely less important – because the moderator turned the whole thing into a kind of "what's your favorite street in LA?" quiz. Without going further into why that bothered me – such as the rather obvious fact that an event about "great streets" really has nothing at all to do with "your favorite street in LA," which both narrows the topic and makes everyone waste time thinking about how they can out-cool one another, coming up with more and more obscure streets that only they have the poetic sense to celebrate – I just want to point out a few quick things. First of all, I think it was only mentioned twice that a street can be anything other than infrastructure devoted to automotive transport – in other words, "streets" inherently just mean space for cars. For instance, the moderator reversed his own question at one point and asked: "What's your least favorite street in LA?" And he explained himself by adding something like: "You know, a street you get irritated on while driving." The whole thing was about cars. Not only did this totally contradict the way the event pitched itself – after all, it should have been billed as a public conversation in which you get to listen to strangers explaining what streets in LA they like to drive on and why (thus attracting a totally different audience) – but it missed so many opportunities in which to talk about great streets. After all, it was an event about great streets. Something that become immediately clear, for instance, was that no one's favorite street was a pedestrian-only walkway through New York City's Central Park, or, say, Pearl Street in Boulder, Colorado (of course, neither of those are in LA – further demonstrating the weird absurdity of limiting a conversation about "great streets" to "cool drives across Los Angeles"). For that matter, no one mentioned that their favorite street was a walking path on the campus of UCLA or Oxford. But that's because people seem to hear the word "street" and they immediately assume it means cars – a "street" means infrastructure for the near-exclusive use of trucks and automobiles. A street means something I can drive my car on.  In fact, something I think about more and more lately is the possibility that Americans get as nostalgic as they do about college – identifying themselves as graduates of certain universities to a degree, and with a passion, that I genuinely think is alien to most cultures – whatever that means – not simply because college represents the only four years in which they might have pursued their real interests, but because, in the United States, college is a totally different lifestyle. You walk everywhere. The campus where you live and study has trees, and paths, and benches to sit on. It's really nice. No wonder you miss it. You can go outside and throw a football, or throw a frisbee, and you can ride a bike – and you don't have to worry about being hit by a truck, or sprayed in the face by several pounds' worth of carcinogens (such as car exhaust). In other words – and this theory is transparently absurd, but I nonetheless think that its rhetorical value is such that I'll give it space here – if you look at the particular colleges in the United States that seem to inspire the highest levels of lifelong loyalty, nostalgia, and even sports team fanaticism, you'll find places like the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor, or UCLA, or my own school, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, or even Penn State, or Georgetown – but the unifying factor there is not simply that all those schools have awesome sports teams, which they do, but that they all have really nice campuses. So you graduate with your law degree and you move to Ft. Worth and you hang Michigan banners all over your office walls – but that nostalgic loyalty is not simply because you miss playing beer pong, it's because you miss being able to walk around everywhere. It's a particularly intense form of pedestrian nostalgia. In any case, college is like discovering a different world, tucked away inside the United States – and it's a world that's been built for human beings. After all, you get at least a tiny bit of exercise everyday; you wake up, drinking coffee outside on the way to class or to work; you don't worry about parking, or about auto theft; you see familiar people hanging out, and you can even stop off and talk to them, standing under oak trees. You can jump around and be a total moron in your own body, outside with the friends who actually know you. But if you do that now, commuting to work in an automobile, you get pulled over by state troopers, tasered in the face – and then you show up on Boing Boing. It's a different world. It's not a world built for you anymore. It's a world built for cars. In many ways, it's as if being an adult in the United States really means changing your everyday landscape. Instead of benches, paths, people, and sunlight, you get cars, parking lots, strangers, and road rage. If you lived in a city that looked like a college campus, you could walk to the bank; you could walk to the grocery store; you could walk to work; you could even walk to the cinema and see Spiderman 3 – and you wouldn't have to do it alongside cars, or even crossing the paths of cars. You'd live and work and commute on foot, walking on great streets under awesomely huge and beautiful trees – and there'd be benches to sit on, and people you know outside reading books, and you could actually understand what it means for "a day" to pass by. After all, there's evening, and there's mid-day, and there's morning – and so you'd actually experience the passage of time. You wouldn't have to look back at the age of 35 and wonder where all that time went. Anyway, I don't care if you're walking to a church or to a gun range, to a mosque or to a nightclub – the point is that you're out there walking, feeling proud – you're not mistaking a linked series of carcinogenic parking lots for the best your nation can do – and streets no longer have to mean cars. Cars are awesome – I love cars, in fact I literally fantasize about owning a Toyota Tacoma. Which is a truck. But cars are for highways, and for hauling things, and for escaping wild bear attacks. Cars are for going camping, and for driving to Baltimore because you're bored and DC sucks. But cars are not for everyday urban use.  If I can be permitted to go on a tiny bit longer here, let me also mention one more thing. Living out here in LA, I'm increasingly convinced that Americans simply don't see how much paved space they're surrounded by at any given moment. There's an intersection in Los Angeles, for instance, just south of Beverly Center – and it's so ridiculously huge that I think you could fit Trafalgar Square, the Piazza San Marco, Rittenhouse Square, and, say, Berlin's Monbijouplatz all tucked safely inside of it. In other words, it could be a pedestrian wonderland of benches and trees and places to lie out in the sun, and throw a baseball, and whatever else it is that you want to do out there under the skies of California. Instead, it's an intersection – and it's one of the largest expanses of concrete I've ever seen. I genuinely believe that if you measured the total square footage of that intersection alone, you'd see that at least three or four of the "great squares of Europe" would fit right in. Conversely, if you took all the piazzas, squares, parks, and plazas of Europe, and you turned them into parking lots, even a city like Bologna could look an awful lot like Los Angeles. In any case, this week's "great streets" event missed so many opportunities to discuss great streets as if they might be something other than just more space for automobiles – or that the open space between opposing buildings should be used for any other purpose than driving on. There was no recognition that streets can be places to walk, or bike, or jog, or hang out with your kids, or flirt with foreign tourists, where you can read a book, and get a tan, and throw objects at your bestfriend so that he can catch them and throw them back at you, repeatedly, in a sportsman-like fashion – that would be a great street, too, in other words, and yet cars would be nowhere to be found. Not even Toyota Tacomas. As I say, finally, I'm not "anti-car" – despite that fact that we're running out of oil. I just don't think that cars should be even remotely convenient when it comes to personal travel within cities. Sorry. It was just depressing to realize that the moderator at the event the other night was obsessed with a new plan out here to turn Pico and Olympic Boulevards into one-way express routes, running east and west across Los Angeles; which seemed to prove, somehow, that the infrastructure of the city should, in all cases, keep pace with car ownership. What was genuinely never discussed, though, was not the idea that we need more highways and parking lots and one-way express lanes because everyone owns a car, but that everyone owns a car because they're surrounded by highways and parking lots and one-way express lanes. What else are you supposed to do in that kind of landscape? How else can you react? In other words, the space comes first; with this many parking lots, you can't walk anywhere. So, even as it was announced that Los Angeles is the most polluted city in the country, and even as LA is now expanding several highways and investing what appears to be absolutely nothing in cool transportation ideas – such as pimped-out mini-buses or light rail – this event, meant as a way to discuss "the importance of greening the public realm," so that our communities can become "inherently more walkable," turned into a celebration of driving in Los Angeles. Which is great – I love driving in Los Angeles. I even have a few favorite streets here. But: 1) A "street" is not simply space devoted to automobiles. It's a place of movement, outdoors, that connects different destinations.

2) Cities could be designed to look like college campuses, full of trees and paths and benches and interchangeable varieties of long walks between different locations – whether those locations are churches, bookstores, police stations, football stadiums, private homes, or hash bars.

3) The reason you need a car is because you're surrounded by highways and parking lots – it's not the other way around. City planners need to realize this. But none of that ever came up the other night. It was a missed opportunity. Not that I chimed in; lamely, I left the minute it ended and walked home to eat some dinner.

|

|

[Image: Looking through the porous facade of the Storefront for Art and Architecture].

[Image: Looking through the porous facade of the Storefront for Art and Architecture]. [Image: Dan Hill, live-blogging Postopolis!].

[Image: Dan Hill, live-blogging Postopolis!].

[Image: Dan Hill and Bryan Finoki sit inside the Storefront for Art and Architecture].

[Image: Dan Hill and Bryan Finoki sit inside the Storefront for Art and Architecture]. [Image: Bryan Finoki, Jill Fehrenbacher, and Joseph Grima at the Storefront for Art and Architecture; unlike Jill and Joseph, Bryan is actually watching a baseball game...].

[Image: Bryan Finoki, Jill Fehrenbacher, and Joseph Grima at the Storefront for Art and Architecture; unlike Jill and Joseph, Bryan is actually watching a baseball game...].

[Images: (top) Jill Fehrenbacher and Bryan Finoki watch either Geoff Manaugh or Dan Hill give a presentation; (bottom) Bryan Finoki, Joseph Grima, Geoff Manaugh, and Dan Hill set up for the day, inside the Storefront for Art and Architecture].

[Images: (top) Jill Fehrenbacher and Bryan Finoki watch either Geoff Manaugh or Dan Hill give a presentation; (bottom) Bryan Finoki, Joseph Grima, Geoff Manaugh, and Dan Hill set up for the day, inside the Storefront for Art and Architecture]. [Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: Winston Churchill visits the ruins of Coventry Cathedral, 1942; courtesy of the

[Image: Winston Churchill visits the ruins of Coventry Cathedral, 1942; courtesy of the  To make a long story still rather long...

To make a long story still rather long...  Further, since I'll more or less be writing this thing over the next six months, I'd love it – love it! – if BLDGBLOG readers wanted to make suggestions, or send me links, or leave comments, or tell me what to avoid...

Further, since I'll more or less be writing this thing over the next six months, I'd love it – love it! – if BLDGBLOG readers wanted to make suggestions, or send me links, or leave comments, or tell me what to avoid...  So...

So...  [Image: What the facade of the Storefront for Art and Architecture will look like if we get to plaster it with our logos...

[Image: What the facade of the Storefront for Art and Architecture will look like if we get to plaster it with our logos...  [Image: Future

[Image: Future  [Image: NASA's TransHab module, attached to the International Space Station. TransHab designed by Constance Adams; image found via

[Image: NASA's TransHab module, attached to the International Space Station. TransHab designed by Constance Adams; image found via  [Image: NASA's TransHab module; image via

[Image: NASA's TransHab module; image via  [Image: The TransHab, cut-away to reveal the exercise room and a "pressurized tunnel" no home in space should be without. Image via

[Image: The TransHab, cut-away to reveal the exercise room and a "pressurized tunnel" no home in space should be without. Image via

[Images: Georgi Petrov, courtesy of

[Images: Georgi Petrov, courtesy of  [Image: A green Trafalgar, via the

[Image: A green Trafalgar, via the  If you could make your house smell like urine, in other words, all your possessions would be permanently safe...

If you could make your house smell like urine, in other words, all your possessions would be permanently safe...  [Image: The final night of the architecture and film festival. From left-right, top-bottom: the

[Image: The final night of the architecture and film festival. From left-right, top-bottom: the  [Image: A scene from Peter Kidger's The Berlin Infection, produced as part of Kidger's work with the Bartlett School of Architecture's

[Image: A scene from Peter Kidger's The Berlin Infection, produced as part of Kidger's work with the Bartlett School of Architecture's  [Image: Outside the wind tunnel – a building rehabbed by

[Image: Outside the wind tunnel – a building rehabbed by  [Image: An underground "coffin lift or 'catafalque'," from London's

[Image: An underground "coffin lift or 'catafalque'," from London's  [Images: Photos by Neil Burns capture the destruction; via the

[Images: Photos by Neil Burns capture the destruction; via the

[Images: Photos by Andrew Turner and John Smith; via the

[Images: Photos by Andrew Turner and John Smith; via the  [Images: Via

[Images: Via  And so I was thinking today that you could go around Manhattan with a microphone, asking people who have had that dream to describe it, recording all this, live, for the radio – or you ask people who have never had that dream simply to ad lib about what it might be like to discover another room, and you ask them to think about what kind of room they would most like to discover, tucked away inside a closet somewhere in their apartment.

And so I was thinking today that you could go around Manhattan with a microphone, asking people who have had that dream to describe it, recording all this, live, for the radio – or you ask people who have never had that dream simply to ad lib about what it might be like to discover another room, and you ask them to think about what kind of room they would most like to discover, tucked away inside a closet somewhere in their apartment. [Image: From the series

[Image: From the series  [Image: From the series

[Image: From the series  [Image: From the series

[Image: From the series  [Image: From the series

[Image: From the series  According to the BBC, Indian officials have concluded that a "

According to the BBC, Indian officials have concluded that a " A poster for

A poster for  [Image: Courtesy of

[Image: Courtesy of  A bachelor is alone, after all, which means that "so much the smaller a space is considered sufficient for him."

A bachelor is alone, after all, which means that "so much the smaller a space is considered sufficient for him." [Image:

[Image:  More to the point here, when Bevan points out that "the bulldozed remains of the

More to the point here, when Bevan points out that "the bulldozed remains of the  For instance, all the gravel, dirt, and foundation stones from ruined buildings and cities around the world could be dropped into shallow waters off the western coast of Greece – forming the base of an artificial island, as large as Manhattan, on which to build your memorial to cities and spaces killed by war...

For instance, all the gravel, dirt, and foundation stones from ruined buildings and cities around the world could be dropped into shallow waters off the western coast of Greece – forming the base of an artificial island, as large as Manhattan, on which to build your memorial to cities and spaces killed by war...  [Image: Ameyoko by

[Image: Ameyoko by  [Image: Ginza Chuo Dori by

[Image: Ginza Chuo Dori by

[Images: Kabukicho, Shibuya Center Town, and Electric City by

[Images: Kabukicho, Shibuya Center Town, and Electric City by  [Image: Hashima by

[Image: Hashima by  [Images: The event, photographed by Nicola Twilley. From left to right, top to bottom, you're seeing the

[Images: The event, photographed by Nicola Twilley. From left to right, top to bottom, you're seeing the

[Image: A street in Central Park, via

[Image: A street in Central Park, via  In fact, something I think about more and more lately is the possibility that Americans get as nostalgic as they do about college – identifying themselves as graduates of certain universities to a degree, and with a passion, that I genuinely think is alien to most cultures – whatever that means – not simply because college represents the only four years in which they might have pursued their real interests, but because, in the United States, college is a totally different lifestyle.

In fact, something I think about more and more lately is the possibility that Americans get as nostalgic as they do about college – identifying themselves as graduates of certain universities to a degree, and with a passion, that I genuinely think is alien to most cultures – whatever that means – not simply because college represents the only four years in which they might have pursued their real interests, but because, in the United States, college is a totally different lifestyle.  If I can be permitted to go on a tiny bit longer here, let me also mention one more thing.

If I can be permitted to go on a tiny bit longer here, let me also mention one more thing.