|

|

[Image: Professor Igor Panarin's six-fold vision of a disintegrated United States; I love how it will precisely follow today's existing state lines – and that Kentucky will join the European Union]. [Image: Professor Igor Panarin's six-fold vision of a disintegrated United States; I love how it will precisely follow today's existing state lines – and that Kentucky will join the European Union].In what sounds to be very obviously an act of wishful projection, a former KGB intelligence analyst turned public intellectual named Igor Panarin has explained to the Wall Street Journal that the United States only has about 18 months left to live. In the summer of 2010, it will "disintegrate" into six politically separate realms – and, conveniently for a thinker who clearly leans to the right, the borders of these realms will coincide with a new racial segregation. The fantasy of living amidst people who don't look like you will come to an end. Best of all, from Panarin's perspective, Alaska – Sarah Palin included, looking out with alarm from her office window – will "revert" to Russian control. Quoting at length: [Prof. Panarin] predicts that economic, financial and demographic trends will provoke a political and social crisis in the U.S. When the going gets tough, he says, wealthier states will withhold funds from the federal government and effectively secede from the union. Social unrest up to and including a civil war will follow. The U.S. will then split along ethnic lines, and foreign powers will move in.

California will form the nucleus of what he calls "The Californian Republic," and will be part of China or under Chinese influence. Texas will be the heart of "The Texas Republic," a cluster of states that will go to Mexico or fall under Mexican influence. Washington, D.C., and New York will be part of an "Atlantic America" that may join the European Union. Canada will grab a group of Northern states Prof. Panarin calls "The Central North American Republic." Hawaii, he suggests, will be a protectorate of Japan or China, and Alaska will be subsumed into Russia. "People like him have forecast similar cataclysms before, he says, and been right," the Wall Street Journal continues. Panarin then "cites French political scientist Emmanuel Todd. Mr. Todd is famous for having rightly forecast the demise of the Soviet Union – 15 years beforehand. 'When he forecast the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1976, people laughed at him,' says Prof. Panarin." In some ways, I'm reminded of Paul Auster's newest novel, Man in the Dark, in which a civil war has set multiple regions of the United States against one another and against the so-called Federal Army. Or, for that matter, there's also Rupert Thomson's Divided Kingdom in which the UK has been split up along emotional lines. But surely an ex-CIA operative, now milking the lecture circuit for all its worth, could also propose a realistic scenario in which the entire Russian east has been sold off, say, to a combination of Euro-American agribusiness firms and the Chinese government, who them embark upon an elaborate, generations-long act of industrial deforestation? Leaving Moscow a kind of irrelevant, feudal city full of Bulgari and handguns, its governmentally terrorized tower blocks populated almost entirely by unemployed and half-drunk retro-Stalinists? I don't mean to imply that I think the end of the United States is somehow politically unimaginable, but that, in a still-bipolar, post-Cold War international imagination, surely either side could convincingly outline the other's demise? (Via Alexis Madrigal. Earlier on BLDGBLOG: North America vs. the A-241/BIS Device and The Lonely Planet Guide to Micronations: An Interview with Simon Sellars).

[Images: From a short film by Michael Aling, produced for Nic Clear's Unit 15 at the Bartlett]. [Images: From a short film by Michael Aling, produced for Nic Clear's Unit 15 at the Bartlett].A few days ago, Ballardian posted a long, well-timed, and very interesting interview with Nic Clear, from London's Bartlett School of Architecture. I've long been a fan of Clear's work with his students; I wrote a short article about him for Dwell last spring (see image, below), and Clear organized last month's Science Fiction and Architecture panel in London.  [Image: A short article about Nic Clear from the March 2008 issue of Dwell]. [Image: A short article about Nic Clear from the March 2008 issue of Dwell].Huge sections of the interview, in which they discuss the value of extra-architectural ideas in helping to shape the "near future" of spatial design, are worth quoting in full; but I'll stick to a few specific moments here, and you can then go read the rest. What I like about Clear, though, is that he's 100% comfortable with – and seemingly relentless about pursuing – architecture not as a system of codified ornament or as a closed universe of citational conformity open only to grad students, but as a resource for ideas of every kind, whether or not they apply to your own local building codes or will ever lead to an act of construction. Want to write a novel? A screenplay? An essay about landscape and climate change? Want to direct a music video? Start a blog? Architecture offers fuel – and amazing visuals – for all of these things. The field becomes almost infinitely more exciting when you realize that architectural projects, by definition, entail the reimagination of how humans might inhabit the earth – how they organize themselves spatially and give shape to their everyday lives. Architecture is, within mere instants of discussing any idea or project, real or imagined, something with anthropological, economic, legal, libidinal, seismic, and even planetary implications. In fact, if architecture can be viewed as the material alteration of the earth's surface, then it is not a stretch to say that architecture has astronomical consequences: it can alter the very shape of a planet. Little wonder, then, if we do decide to go in this direction, that there appears to be a growing cross-over of interests between architecture and science fiction – as in, for instance, the work produced by Nic Clear's Unit 15.    [Images: From a short film by Dan Farmer, a tour through a landscape of abandoned hospital equipment, produced for Nic Clear's Unit 15 at the Bartlett]. [Images: From a short film by Dan Farmer, a tour through a landscape of abandoned hospital equipment, produced for Nic Clear's Unit 15 at the Bartlett].In any case, it shouldn't be surprising that Ballardian would then focus specifically on the architectural value of J.G. Ballard. When asked whether Ballard is a growing influence on today's practitioners, Clear answers: I’m not sure how many architects are being influenced by Ballard in their work, especially within ‘commercial’ architecture – maybe the forthcoming recession will make architects aware of the Ballardian possibilities of architecture. Within academia and architectural criticism, if such a thing still exists, there is a general disdain for ‘popular’ fiction – writing on, and about, architecture is still very elitist – and I have met quite a bit of resistance when discussing Ballard as a serious subject. However, I think that there is a desire to face up to a future that deals with a system in crisis, which Ballard articulates so brilliantly. I was recently reading Mike Davis’s breathtaking collection of essays, Dead Cities, and was constantly thinking ‘this is so Ballardian.’ Also, writers like Frederic Jameson and Jean Baudrillard, who have been influenced by Ballard, are still incredibly important and influential. Obviously Ballard’s early identification of global environmental issues also makes him incredibly pertinent to many people. However Ballard does not give easy, or even any answers and this puts off many people. Given the current economic and environmental conditions, he seems more prescient than ever, not simply because of the situations he describes, but because he offers a mindset for dealing with these issues. Asked to define "Ballardian space," if such a thing exists, Clear says: "If you take Jameson’s postmodern hyperspace, remove the post-structuralist jargon, add some dark humour and set it on the periphery of any declining western industrialised city – especially London – then you are pretty close [to Ballardian space]." Finally – because you can simply read the interview itself in full – Clear sums it all up: "We have to stop thinking about architecture simply in terms of building buildings – that’s why I am so interested in looking at other models and disciplines to draw inspiration from."

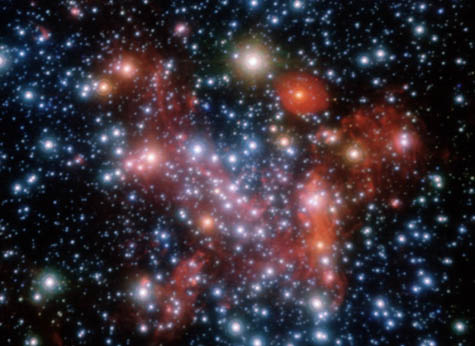

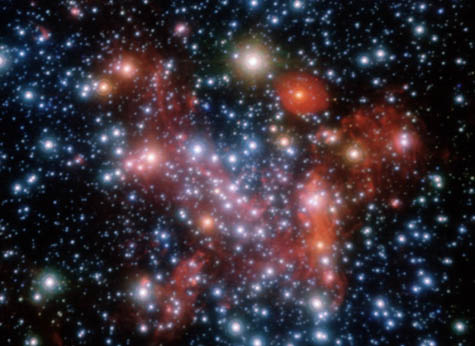

[Image: The dark skies above Galloway Forest Park, Scotland, via the Guardian].Note: This is a guest post by Nicola Twilley. [Image: The dark skies above Galloway Forest Park, Scotland, via the Guardian].Note: This is a guest post by Nicola Twilley.2009 has been designated by the United Nations as the International Year of Astronomy (IYA), marking the 400th anniversary of Galileo’s telescope. The excitement is starting early, with Galloway Forest Park in Scotland announcing its plans to become Europe’s first “dark sky park.” The forest, which covers 300 square miles and includes the foothills of the Awful Hand Range, rates as a 3 on the Bortle scale. The scale, created by John Bortle in 2001, measures night sky darkness based on the observability of astronomical objects. It ranges from Class 9 – Inner City Sky – where "the only celestial objects that really provide pleasing telescopic views are the Moon, the planets, and a few of the brightest star clusters (if you can find them)," to Class 1 – Excellent Dark-Sky Site – where "the galaxy M33 is an obvious naked-eye object" and "airglow… is readily apparent." Class 3 is merely "Rural Sky," meaning that while "the Milky Way still appears complex... M33 is only visible with averted vision."  [Image: The Pleiades, photographed by Thackeray's Globules, photographed by Hubble]. [Image: The Pleiades, photographed by Thackeray's Globules, photographed by Hubble].Nonetheless, Galloway Forest Park contains the darkest skies in Europe, and Steve Owens, co-coordinator of the IYA plans in the UK, is determined to gain recognition from the International Dark-Sky Association (IDA) as a lasting legacy for the 2009 celebrations. The certification process is challenging. According to the Guardian, "to earn dark sky park status, officials in Galloway will submit digital photographs of the night sky taken through a fisheye lens. Their application must be supported by readings from light meters at different points in the park, and a list of measures that are being taken within the forest to prevent lights in and around the handful of farm buildings from spilling upwards into the sky and ruining the view." The IDA website itself contains everything that "locations with exceptional nightscapes" need to know to submit their application to be certified as "International Dark Sky Communities (IDSC), International Dark Sky Parks (IDSP), and International Dark Sky Reserves (IDSR).” Currently, there is only one dark-sky community in the world (Flagstaff, AZ), and just two dark-sky parks (the first, Natural Bridges National Monument in Utah, and the slightly less well-known Cherry Springs State Park in northern Pennsylvania). There are no actual reserves yet; indeed, the concept is still being thrashed out in partnership with UNESCO (who issued their own Starlight Reserve framework in 2007).    [Images: The "center of the Milky Way," photographed by the European Southern Observatory at al.; the galaxy NGC 281, photographed by Ken Crawford of the Rancho Del Sol Observatory; and the Pleiades, photographed by Philip L. Jones]. [Images: The "center of the Milky Way," photographed by the European Southern Observatory at al.; the galaxy NGC 281, photographed by Ken Crawford of the Rancho Del Sol Observatory; and the Pleiades, photographed by Philip L. Jones].The idea of a human-created dark sky park is fascinating, of course, as are the architectural and landscape modifications that must be undertaken by town councils and park management services in order to secure a qualifying Bortle score. For example, Observatory Park in Montville Township, Ohio, has been awarded provisional IDSP status (Silver Tier), contingent on "the completion of the park’s outdoor lighting scheme, visitor’s center, and enactment of outdoor lighting ordinances in surrounding townships." The Geauga Park District submitted their 34-page Lighting Management Plan (read the PDF) in August 2008, detailing various proposals for the reduction of local skyglow (as opposed to natural airglow), light trespass, and glare. These include full shading for all light installations and lighting curfews, as well as strategic tree planting. The concept of shaping the ground to frame and enhance the sky is not new (for instance, James Turrell’s Skyscapes are an architectural attempt to achieve " light effects and perceptual events" centered on a complex reframing of the sky). Nonetheless, the idea of rebuilding and landscaping an entire community specifically for the purposes of experiencing darkness is an exciting one – as is the idea of UNESCO, official protector of World Heritage Sites, attempting to safeguard dark skies as a "natural and cultural property." Scotland, with its northerly latitude and constant rain (which cleans the atmosphere of dust), has perhaps discovered its global tourist niche: A spokesman for VisitScotland, which is working closely with Dark Sky Scotland, ventured that "the night sky could be as important for tourism as the landscape."

[Image: Sludge makes itself at home in Harrimann, Tennessee; photo by J. Miles Carey/Knoxville News Sentinel, via Associated Press/New York Times]. [Image: Sludge makes itself at home in Harrimann, Tennessee; photo by J. Miles Carey/Knoxville News Sentinel, via Associated Press/New York Times].Earlier this week the retaining wall of a massive sludge dam gave way 40 miles west of Knoxville, Tennessee, resulting in a coal ash spill that now lies "thick and largely untouched over hundreds of acres of land and waterways." Houses and business have been buried whole or swept off their foundations by the potentially toxic material; amidst its unnaturally concentrated ingredients are selenium, arsenic, and lead, all of which produce "neurological problems" and cancer. "The breach occurred," the New York Times explains, as if describing a painting by from a little-known Appalachian Series by Caspar David Friedrich, "when an earthen dike, the only thing separating millions of cubic yards of ash from the river, gave way, releasing a glossy sea of muck, four to six feet thick, dotted with icebergs of ash across the landscape. Where the Clinch River joined the Tennessee, a clear demarcation was visible between the soiled waters of the former and the clear brown broth of the latter." An updated aerial survey now suggests that more than 5 million cubic yards of this possibly neurologically-active waste has been released – "enough to flood more than 3,000 acres one foot deep" – forming a new self-organized landscape of industrial byproducts, a future stratigraphic surprise for our next millennium's archaeologists. Or perhaps this is the metallization of the world long ago dreamed of by the Italian futurists. Adventures in metallized deterrestrialization.

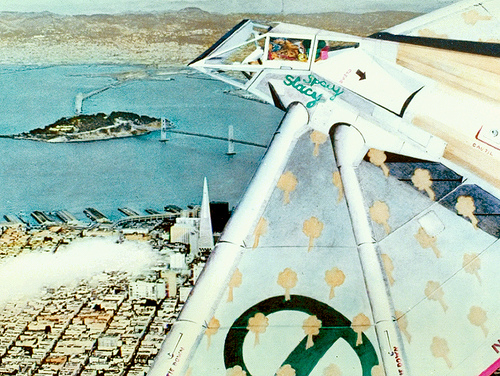

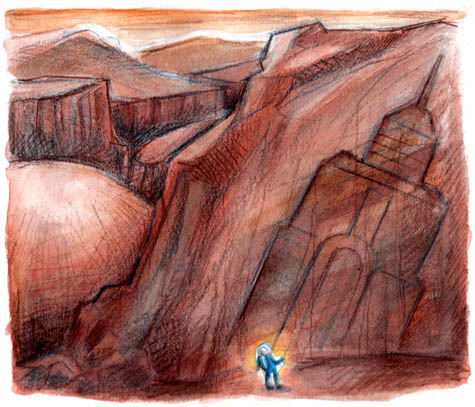

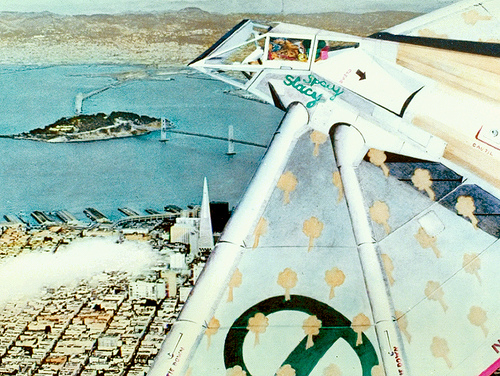

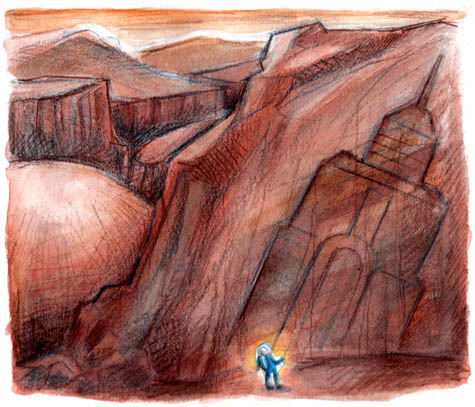

[Image: By Craig Hodgetts, from his prospective drawings for a film adaptation of Ecotopia]. [Image: By Craig Hodgetts, from his prospective drawings for a film adaptation of Ecotopia].Over on the Architect's Newspaper Blog, Ken Saylor takes a look at the novel Ecotopia, recently discussed by The New York Times. Amusingly, that novel's key phrases, according to Amazon.com, include "extruded houses," "ritual war games," "forest camp," and "San Francisco." However, what the NYT fails to mention, Saylor adds, is that, in 1978, architect Craig Hodgetts "produced a wondrous set of drawings for a Hollywood movie adaptation of the pulp classic. With plenty of savvy and pop-culture sensibility, the script was translated into awe-inspiring architectonic visuals. The drawings were exhibited and published, but alas, the project never made it to the silver screen." The images include solar-powered, high-speed maglev trains that "utilize a 'lifting body' profile to reduce gravity forces at speed, allowing lightweight bridges that act in tension rather than compression," as well as "balloon generators over San Francisco Bay," complete with their associated "maintenance gondolas." Check out the original post for more images – with captions by Hodgetts himself – and more information about the unfortunately undeveloped film adaptation. However, I have to add, briefly, that architecture is by its very nature a specific form of science fiction: whether we're using it to design luxury high-rises, modular refugee camps, solar towers, or complete urban ecotopias, architecture gives us the means, on par with literature and mythology, through which we can re-imagine the world. Architecture, by definition, is speculation about the future.

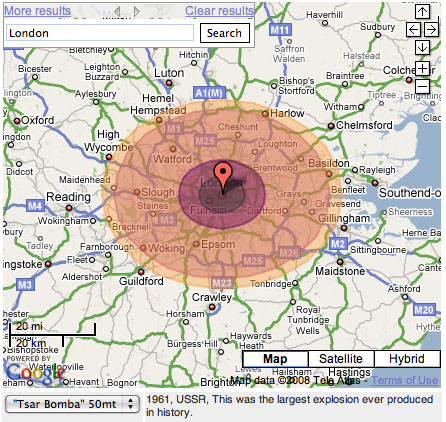

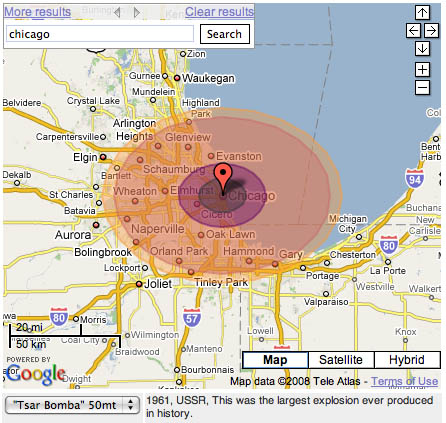

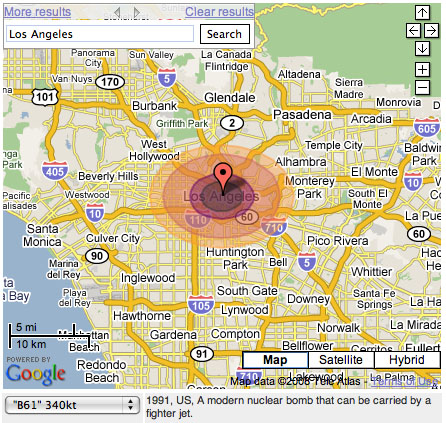

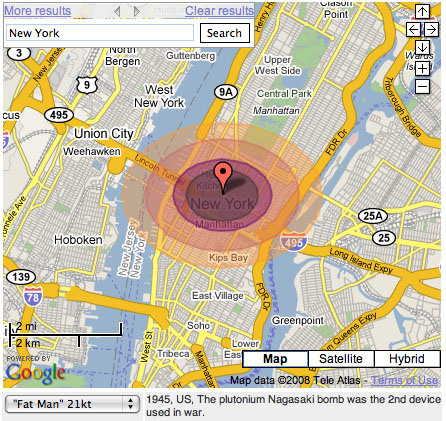

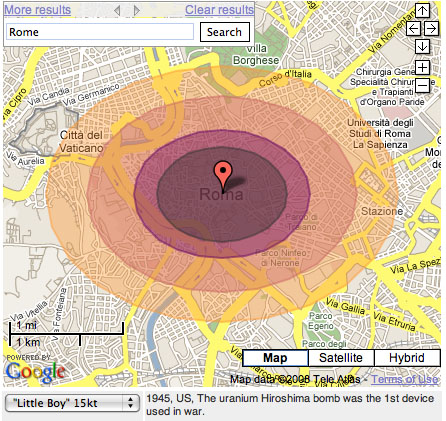

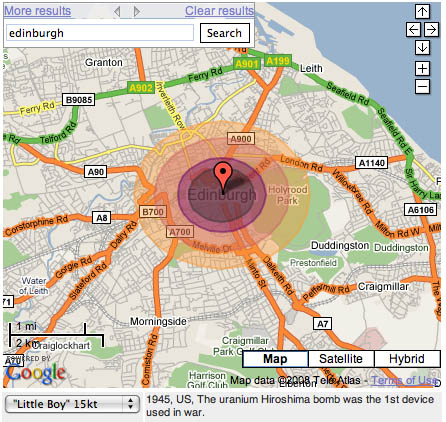

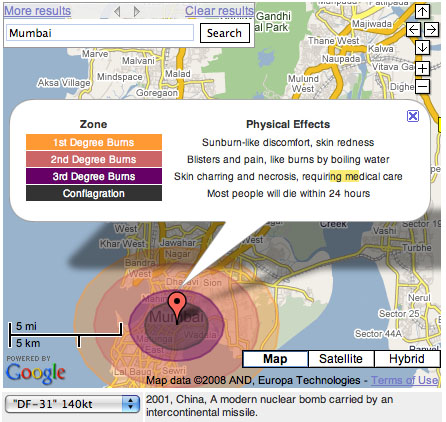

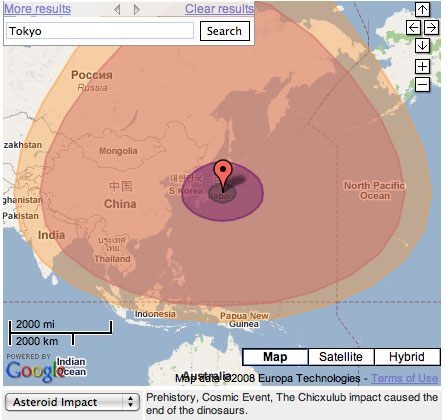

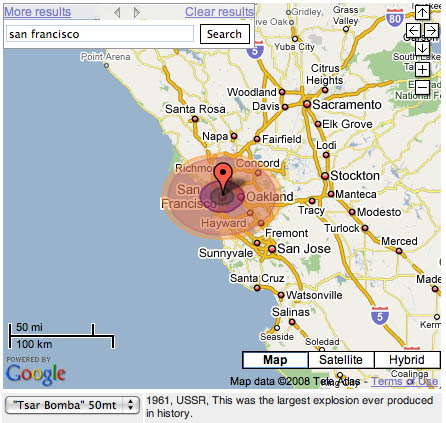

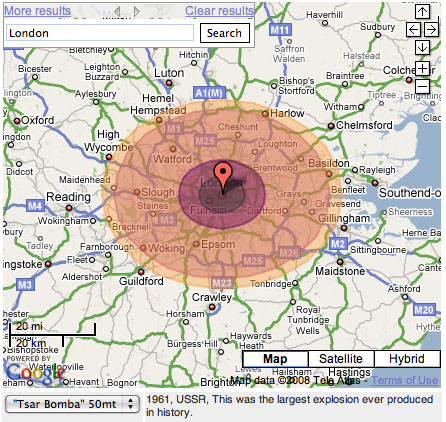

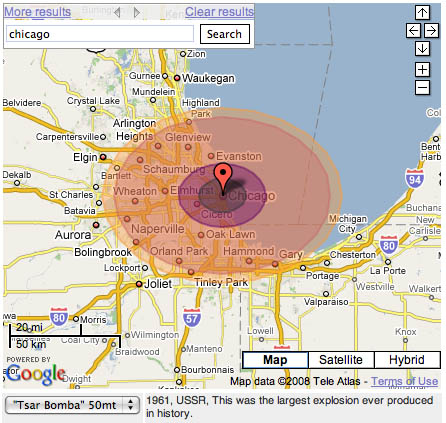

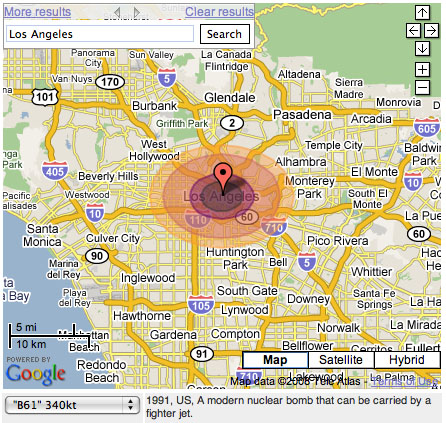

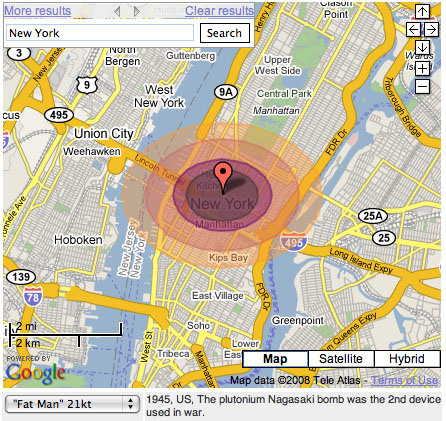

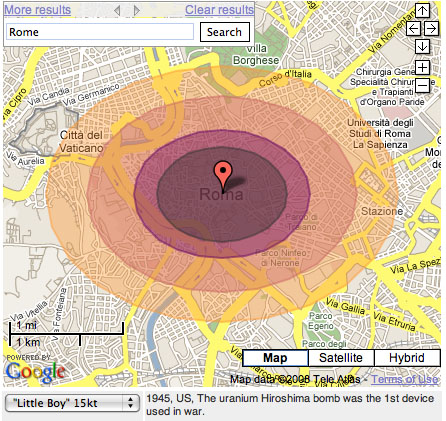

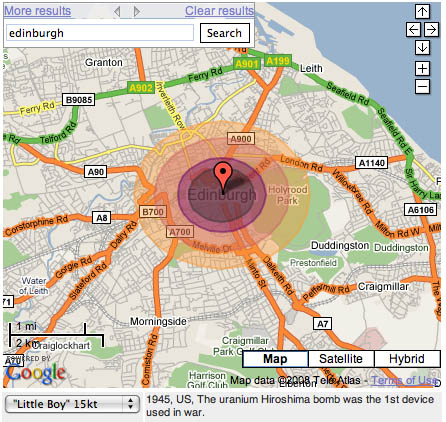

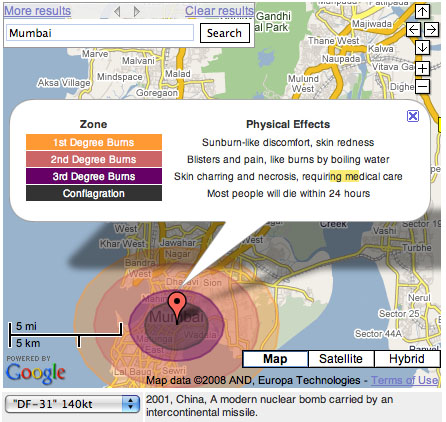

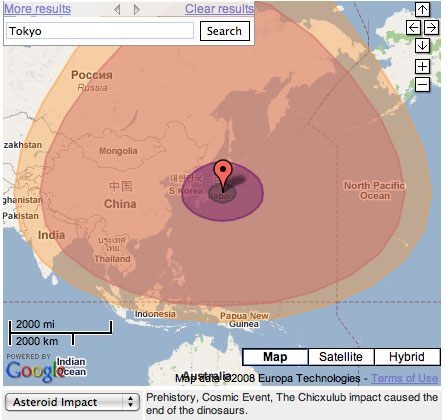

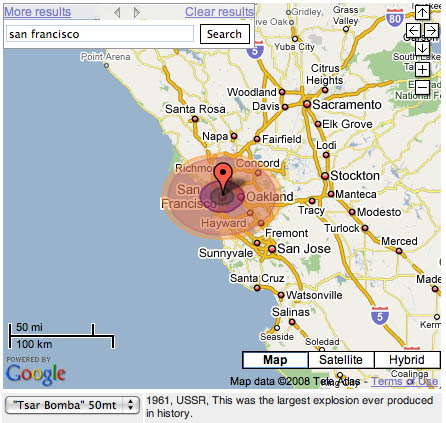

A Google Maps mash-up by Sydney-based design firm CarlosLabs has us looking at what nuclear explosions would do to cities all over the world.  [Image: London nuked, courtesy of CarlosLabs]. [Image: London nuked, courtesy of CarlosLabs]."This mapplet," we read, "shows the thermal damage caused by a nuclear explosion. Search for a place, pick a suitable weapon and press ' Nuke It!'" The image you see above is London as decimated by an atomic bomb equivalent to the freakishly terrifying Soviet Tsar Bomba test of 1961. Everything as far as Guildford has been damaged – the entire center of the city simply gone. Below, we see Chicago obliterated by the same size of explosion. Looking closely, we see that the difference between a first- and second-degree burn – and this information is explained a bit more, below – passes directly through the distant suburban town in which I was born, Highland Park.  [Image: Courtesy of CarlosLabs]. [Image: Courtesy of CarlosLabs].Waters along the shore of Lake Michigan would be instantly evaporated, forming radioactive rainstorms over northern Indiana, perhaps for days. The size of the bomb can be varied, of course; here we see Los Angeles hit by any typical nuclear warhead carried by an American fighter jet, circa 1991; and, below that, we see New York City hit by a bomb equivalent to Fat Man, the device dropped on Nagasaki.   [Images: Courtesy of CarlosLabs]. [Images: Courtesy of CarlosLabs].And here, below, is Rome hit by Little Boy, the bomb dropped on Hiroshima – and the first nuclear device ever used as an act of war. If it's any consolation to Catholics – or architectural historians – the extreme, northwestern fringes of the Vatican would escape immediate harm.  [Image: Courtesy of CarlosLabs]. [Image: Courtesy of CarlosLabs].Alternatively, let's drop Little Boy on Edinburgh.  [Image: Courtesy of CarlosLabs]. [Image: Courtesy of CarlosLabs].All of this is visually arresting – seeing vast bruises like bull's eyes consume whole cities – but what does it really mean? What is each colored circle supposed to represent? In the following image of Mumbai being hit by a nuclear missile equivalent to those used by the Chinese military, we see concentric rings of 1st, 2nd, and 3rd degree burns expanding outward from the detonation – a geometry of necrosis, suffocation, and death. Blisters and cancer would affect tens of thousands of people for miles in every direction (depending on prevailing winds).  [Image: Courtesy of CarlosLabs]. [Image: Courtesy of CarlosLabs].For some unexpected astronomical context, though, CarlosLabs has added a bizarre final option: seeing how asteroid impacts might compare with inter-urban nuclear war. Tokyo – where the following image is centered – is not merely erased; struck by an asteroid, it's been placed at the heart of a planetary event, complete with rings of sunburn-equivalent injury spreading out across whole continents.  [Image: Courtesy of CarlosLabs]. [Image: Courtesy of CarlosLabs].Returning to the realm of historical likelihood, the image that somehow clarifies this the most for me – if, for no other reason, because I live there – is the following glimpse of San Francisco. The entire peninsula has been blasted into absolute, smoking oblivion by an explosion equal to Tsar Bomba. The fact that you would be more or less screwed as far south as Fremont – and well east of Oakland – seems sobering, indeed. You could be sitting in the west-facing window of an Oakland high-rise, watching an atomic fireball explode over San Francisco – which quickly expands to melt the glass you're looking through.  [Image: Courtesy of CarlosLabs]. [Image: Courtesy of CarlosLabs].A few quick points, meanwhile: 1) This will mean very little, and have no effect, but I am 100% behind complete nuclear disarmament. The U.S. taking the lead in this seems like something well worth pursuing. 2) In this context, I have to say that the books of Richard Rhodes cannot be recommended highly enough. His The Making of the Atomic Bomb – which I have to confess to having read only partially – is required reading for anyone interested in what intensive, well-funded efforts of design can – in this case, unfortunately – produce. The bomb as an act of national infrastructure. 3) Michael Light's book 100 Suns, a photographic survey of nuclear weapon tests, is as horrifying as it is visually spectacular, especially for anyone with an interest in human history (and its explosive intersection with enriched geology). 4) Gary Snyder has a great poem that I still think of now and again, 17 years after first reading it, called "Bomb Test." Originally written, I believe, in Kyoto in 1986, the poem presents nuclear weapons as a kind of new terrestrial element, something geologically unprecedented both in and on the surface of the earth – highly processed samples of mineral chemistry (uranium, plutonium) put into military service by rival superpowers. "The fish float belly-up, for real," Snyder writes. "Uranium in the whites / of their eyes. They've been swimming

Deep down where it's black when a

Silvery snow of something queer

glinted in

From cirrus clouds to the seamounts,

Through all the food chains,

Shrimp to tuna, the currents,

Riding the waves. This "silvery snow," he suggests, is something outside biological experience altogether. Ironically, though, this is exactly what makes radioactive fallout perhaps the only true, long-term marker of human presence on the earth. It is our greatest fossil, so to speak. Even now, the globally nomadic residues of nuclear weapons tests form a ghostly stratigraphic marker that can be found literally around the world, an all but permanent part of the earth's sedimentary record. So, in the images that illustrate this post, we see what effects this geological discovery – the explosive power of rare elements – could have on the built geography of our species. Nuclear war thus poetically equates to hurling enriched fragments of the earth's surface at your rivals. Call it weaponized geology: minerals made altogether unearthly, if not post-terrestrial, through anthropological intervention. 5) Here is a random assortment of nuclear bomb photography. These were all Cold War-era tests – but, someday, perhaps soon, architects and architecture bloggers will be looking at similar images, images that have captured the obliteration of constructed environments from Mumbai or Karachi to New York, London, or Tehran. This will happen, I would say; it might well occur within our lifetimes, or at least within the next century; and any even partially accurate future assessment of global urbanism must still take nuclear weapons into account. Nuclear weapons present us with a kind of demonic skeleton key, capable of catastrophically unlocking any city in the world, no matter how dense or well-fortified, in mere seconds.  Finally, here is what would happen if a nuclear bomb was dropped on a relatively non-urban environment: in this case, the town of Chapel Hill, North Carolina.  [Image: Courtesy of CarlosLabs]. [Image: Courtesy of CarlosLabs].But this could just as easily have been Ann Arbor, Santa Cruz, Austin, Shrewsbury, Castleton, Aberystwyth, Marburg – it could just as easily have been anywhere on earth. The overwhelming obliterative power of nuclear weapons turns them into a kind of ubiquitous anti-landscape, something that no geography, built or natural, can successfully resist. All of which is simply a long-winded way of saying that while we now tend to measure threats against our cities in terms of armed gangs or contextually minor moments of staged terrorist assault, it's still interesting to remember that, hovering over all of this, is something that could simply annihilate cities altogether. If we're going to study cities, in other words, then we should also study that which is radically anti-city. (Spotted via Alexis Madrigal and Wired Science).

Homes in the Swedish town of Halmstad, the hometown of soccer star and former men's underwear model Freddie Ljungberg, will soon be using excess heat from the town's crematorium to stay warm each winter.  "Officials in the western Swedish town came up with the idea," the Telegraph reports, "after a recent environmental review concluded that the crematorium's chimneys were pumping far too much smoke into the air. Inspectors said the crematorium would have to buy new ovens in order to meet basic environmental standards." "It was when we were discussing all these environmental issues that we started thinking about the energy that is used in the cremations and realised that instead of all that heat just going up into the air, we could make use of it somehow. It was just rising into the skies for nothing," said Lennart Andersson, the director of the cemetery in the town of Halmstad. "For starters we will heat our own premises. But I hope we can connect to the district heating network in the future." A bit more on how it would work: When a body is cremated, toxic materials are released from the corpse. For example, fillings in the teeth, when heated to high temperatures, release mercury. In order to filter out the toxic materials before they are released into the air, the crematorium must cool the smoke from around 1,000ºC to 150ºC. But, with the heat now directed into the public heating system, the smoke will already be much closer to 150ºC and the crematorium will spend less on materials, including water, to cool it down. This might be the most obvious – and least interesting – thing I could say right now, but this sounds an awful lot like the premise of a film – starring Paris Hilton, say – in which joy-riding teens stumble upon an idyllic small town in northern Vermont, or perhaps Minnesota, only to realize that all the homes around them, including the nice B&B in which they've booked a room, are warmed by an underground labyrinth of pipes and tunnels... that gets all its heat from burning corpses. What sound like distant screams coming in through the bathroom air vent at 2 in the morning leads one of them to explore... But what constitutes a morally acceptable source of alternative energy? Who decides? (Thanks to John Devlin for the link!)

[Image: John Constable, Seascape Study with Rain Cloud, 1824]. [Image: John Constable, Seascape Study with Rain Cloud, 1824].Almost exactly a year ago, the Guardian wrote that "huge tracts of Britain's landscape should be reclaimed from farming and go back to nature to lock up carbon dioxide and counter global warming." This would mean, for instance, that "traditional farming would be wound down in marginal areas while some landscapes should be 're-wilded' to absorb more water and reduce flooding downstream. Peat bogs, which can store carbon, must be conserved and restored." The change would not come quick, and it would be controversial, a government ecology expert adds; after all, "There's a deep cultural resistance to the idea of land no longer being farmed," even if that land does have "other values which are now probably much higher for society." Would similar strategies be useful here in the United States? Like some scene from a future, sci-fi-inflected John Steinbeck novel, we'd abandon entire corporate agribusiness complexes to leave those now-lost farms in a state of second nature, re-wilded, gone to seed, subject to a different kind of valuation.

[Image: New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina; photographer unknown]. [Image: New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina; photographer unknown].One of very many interesting points made by Jan Zalasiewicz in his new book The Earth After Us is that rising sea levels in an era of global climate change might actually – ironically – increase humanity's long-term chances of urban fossilization. "If we and our children are very unlucky over the next few decades," he writes, "and the waters rise swiftly, then many of our cities may be as well preserved as Pompeii, as though in aspic." After all, he adds, "if the sea rises quickly enough, and there is not time for the waves to do their work, landscapes may be drowned entire. Only a few meters beneath sea level, and what was the land now lies below the destructive surf zone. A hundred meters below sea level, and even the most violent storm waves can scarcely be felt. So, let the sea flood in, with its level jumping by meters over centuries or decades – or perhaps even years – and there simply will not be time for this wave energy to erode the landscape."  [Image: The aquatic aftermath of Hurricane Ike, photographed by Carlos Barria for Reuters; via The Big Picture]. [Image: The aquatic aftermath of Hurricane Ike, photographed by Carlos Barria for Reuters; via The Big Picture].Then, once everything's underwater, the silting will begin. The planet's submerged coastal and river-delta cities will thus be "covered with sand and mud," entombed within the very landscapes upon which they once rested. This would immediately put these regions beyond the reach of erosion – except perhaps for a little localized scouring by strong tidal currents – and into the kingdom of sedimentation. Our drowned cities and farms, highways and farms, would begin to be covered with sand, silt, and mud, and take the first steps towards becoming geology. The process of fossilization will begin. And then, like some gigantic ribcage from a species no one will fully comprehend, bits of New Orleans and Amsterdam and Hanoi will be unearthed amidst the mudstones of a future geography. So might rapid climate change mean not the complete erasure of humanity's material traces but, with fantastic irony, civilization's geologically long-term preservation?

[Image: Art by Joe Alterio; view larger]. [Image: Art by Joe Alterio; view larger].

I'm thrilled to announce that BLDGBLOG and Wired Science have teamed up with Swissnex to host a live interview—free and open to the public—with University of Leicester geologist Jan Zalasiewicz, author of The Earth After Us: What Legacy Will Humans Leave in the Rocks?, from Oxford University Press.

The event will be from 7-9pm on Wednesday, December 17th, at Swissnex, 730 Montgomery Street, in San Francisco; here's a map.

Zalasiewicz's book offers a fascinating and sustained look at what will happen to the material artifacts of human civilization 100 million years from now, when cities like Manhattan are mere trace fossils in flooded submarinescapes, Amsterdam is an indecipherably fragmentary presence in the lithified mudflats of a new, future continent, and cities like Los Angeles and Zurich have been eroded away entirely by a hundred million years of rockslides and weather.

To quote an early chapter from Zalasiewicz's book at length: The surface of the Earth is no place to preserve deep history. This is in spite of – and in large part because of – the many events that have taken place on it. The surface of the future Earth, one hundred million years now, will not have preserved evidence of contemporary human activity. One can be quite categorical about this. Whatever arrangement of oceans and continents, or whatever state of cool or warmth will exist then, the Earth's surface will have been wiped clean of human traces.

(...)

Thus, one hundred million years from now, nothing will be left of our contemporary human empire at the Earth's surface. Our planet is too active, its surface too energetic, too abrasive, too corrosive, to allow even (say) the Egyptian Pyramids to exist for even a hundredth of that time. Leave a building carved out of solid diamond – were it even to be as big as the Ritz – exposed to the elements for that long and it would be worn away quite inexorably.

(...)

So there will be no corroded cities amid the jungle that will, then, cover most of the land surface, no skyscraper remains akin to some future Angkor Wat for future archaeologists to pore over. Structures such as those might survive at the surface for thousands of years, but not for many millions. The book goes on to explore buried cities, flooded cities, and cities destroyed by erosion; the long-term traces of different materials, from concrete and steel to nuclear waste and industrial plastics; and the future magnetic presence of urban metals that have been compressed into the thinnest bands of underground strata. We'll be talking about cities like New Orleans, London, Hanoi, and Shanghai; New York, Los Angeles, Cairo, and Geneva. What "signals" of their one-time existence will these cities offer in 100 million years' time? About Mexico City, Zalasiewicz writes: Mexico City has a good short-term chance of fossilization, being built on a former lake basin next to active, ash-generating volcanoes; but its long-term chances are poor, as that basin lies on a high plateau, some two kilometers above sea level. The only ultimate traces of the fine buildings of [Mexico City] will be as eroded sand- and mud-sized particles of brick or concrete, washed by rivers into the distant sea. With visions of cities become not spectacular, vine-covered ruins but but vast deltaic fans of multi-colored sand, the book looks at the future geological destinies of everything from plastic cups to clothes.

Alexis Madrigal, from Wired Science, and I will also have five copies of Zalasiewicz's book to give away to attendees, and there will be drinks and light food after the event, so it will be well worth coming out.

If you get a chance, please RSVP at the Swissnex site, so that they can keep track of expected visitors.

(With special thanks to Joe Alterio for the artwork!)

[Image: From Power from the Wind by Palmer Cosslett Putnam]. [Image: From Power from the Wind by Palmer Cosslett Putnam]."In May 1931," author Palmer Cosslett Putnam wrote in his 1949 book Power from the Wind, and "after two years of wind measurement, a wind-turbine 100 feet in diameter was put in operation on a bluff near Yalta, overlooking the Black Sea, driving a 100-kilowatt, 220-volt induction generator, tied in by a 6300-volt line to the 20,000-kilowatt, peat-burning steam-station at Sevastopol, 20 miles distant." As if anticipating BLDGBLOG's recent look at infrastructural domesticity, Putnam points out that "a streamlined house" containing generators was held aloft behind the turbine – but this "house" also offered a temporary place of rest to the maintenance workers who checked up on the turbine's workings. Accessible via a long flight of stairs, this airborne space added a small touch of domestic comfort to an otherwise industrial piece of machinery in the sky. [Sent in by Alexis Madrigal, who also had this image scanned from Putnam's book].

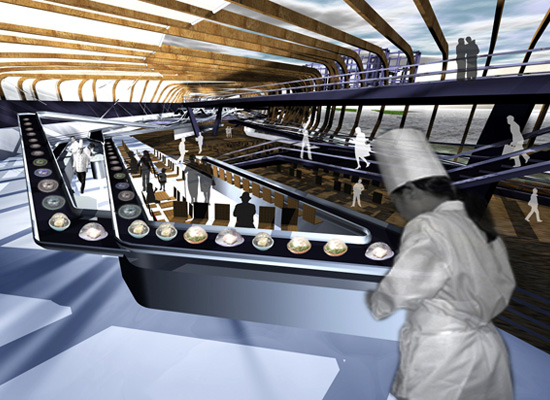

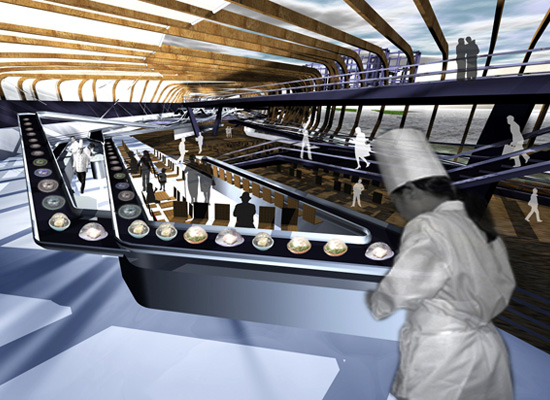

[Image: From a project for fish-farming the Thames by Benedetta Gargiulo, part of a recent design studio at the Architectural Association taught by Nannette Jackowski and Ricardo de Ostos; via Pruned]. [Image: From a project for fish-farming the Thames by Benedetta Gargiulo, part of a recent design studio at the Architectural Association taught by Nannette Jackowski and Ricardo de Ostos; via Pruned].A passing comment on the previous post has me thinking that a fantastic, Pruned-inspired summer architectural studio could be organized around the idea of turning backyard swimming pools not into mausoleum-like, subterranean granny flats, but experimental fish farms and hatcheries, alternative-energy algae-breeding ponds and other avant-garde aquacultural installations. Architecture as artificial ecosystem. Could you reimagine the food production infrastructure of a city through the aquacultural transformation of its backyard swimming pools?

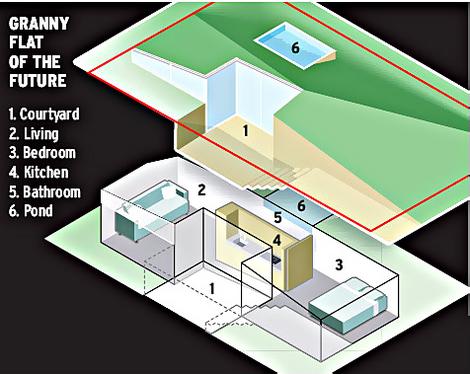

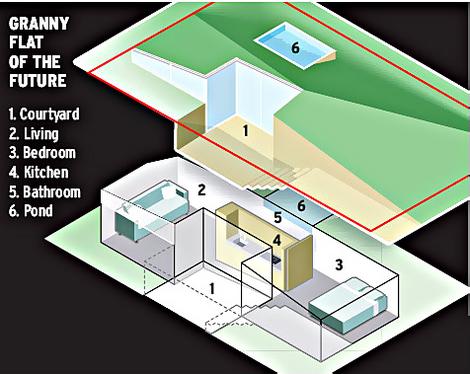

[Image: The subterranean granny flat of the future, via the Sydney Morning Herald]. [Image: The subterranean granny flat of the future, via the Sydney Morning Herald].According to an article published last month in the Sydney Morning Herald, turning backyard swimming pools into subterranean "granny flats" is a spatially innovative, if unexpected, way to assuage Sydney's growing housing shortage. Indeed, much of Sydney's projected population growth could simply be "housed within some of [New South Wales's] 360,000 swimming pools." These "redeveloped pools" could then be used as detached bedrooms for grandparents, teens, guests, bunker enthusiasts, underground-obsessed schizophrenics, and so on. The regions 360,000 swimming pools would first be emptied of their water and then transformed, through architectural intervention, into a comfortable domestic space, "complete with a small bedroom, living room, kitchen, bathroom, garden alcove and rooftop windows." But where would everyone then swim? In the ocean pools of Sydney, of course. (Thanks to Simon Sellars for the tip!)

Last week, Sapporo announced that they would soon be serving space beer, "the world's first beer made with barley descending from plants grown inside the International Space Station." The barley used in the new beer is a third-generation offshoot of the original plant stored for five months in a Russian laboratory in the station. The company has made only 100 liters of the new brew, named Sapporo Space Barley, which is not for sale. Sapporo says the beer is safe because it has tested microbes in it and did tests with lab animals and Sapporo employees, too. It also says that the space beer tastes just like regular beer. For obvious reasons, this brings to mind China's space seed project, in which " space breeding" puts astronomy to work in the service of contemporary agriculture. Plant seeds have been blasted into orbit in the hope that "space breeding" holds the key to improving crop yields and disease resistance. Wheat and barley strains developed by the Department of Agriculture and Food in Western Australia (WA) have just landed back on Earth following a 15-day orbital cruise on board China's Shijian-8 satellite. "Space-breeding refers to the technique of sending seeds into space in a recoverable spacecraft or a high-altitude balloon," said Agriculture WA barley breeder Chengdao Li. "In the high-vacuum, micro-gravity and strong-radiation space environment, seeds may undergo mutation." While this certainly offers landscape architects an unearthly way to boost their horticultural repertoire, it also shows that specialty foods cultivated through genetic interaction with the universe might yet find a comfortable place in the human food chain. Sipping space beer, ingesting astronomical influence, welcoming literally non-terrestrial nutrition into the planetary web of caloric intake, we'll find that Sapporo's newest beer brings a suitably alien tenor to the local amnesia of alcoholic intoxication. (Earlier on BLDGBLOG: Turning endangered landscapes into beer).

If you happen to be near Los Angeles this weekend, I'll be giving a 40-45 minute talk this Saturday at the A+D Museum as part of a day-long event organized by Gensler – designers of the tallest building in China, which began construction last week in Shanghai.  The theme for the day is Design Process Innovation, and my own talk is called "San Francisco As It Should Be" – applying many of the ideas that have been found here on BLDGBLOG over the past few years to the (ironically complacent) city where I now live. From tectonic self-engineering to whole-city sound design, via guerrilla gardening, subterranean mobile libraries, and vertical film clouds, among many other ideas and projects, from Fritz Haeg to Sarah Ross to Steve Lambert and Packard Jennings, I'll be taking a look at a range of ways to alter the face and experience of the city. The event lasts from 10am-5:30pm, and I'll be one of the final keynote addresses – from 3-4pm, I believe. It's not free, unfortunately, but student discounts are available. The other participants include some really fantastic people, including Scott Robertson of Design Studio Press; the awesome Tali Krakowsky from Imaginary Forces – from whom you'll soon hear more when I post BLDGBLOG's long (and very long-delayed) interview with the principals of that firm; Frances Anderton, a colleague of mine at Dwell and host of KCRW's weekly radio show DnA; Sam Lubell of The Architect's Newspaper; and many, many, many more. So if you're in town and need something to think about, consider stopping by. Here's a map – and you can read a bit more about it here, with tickets available for purchase here. If you do make it out, come up and introduce yourself as I'd love to say hello.

Because "it takes too long to come down to ground level each day to make it worthwhile," a crane operator on the Burj Dubai – the world's tallest building – is rumored to have "been up there for over a year," the Daily Telegraph reports.

His name is Babu Sassi, and he is "a fearless young man from Kerala" who has become "the cult hero of Dubai’s army of construction workers." He also lives several thousand feet above the ground.

[Image: The Burj Dubai, via Wikipedia]. [Image: The Burj Dubai, via Wikipedia].

Whether or not this is even true – after all, I never think truth is the point in stories like this – 1) the idea of appropriating a construction crane as a new form of domestic space – a kind of parasitic sub-structure attached to the very thing it's helped to construct (perhaps raising the question: what is the ontology of construction cranes?) – is totally awesome; 2) further, the idea that crane operators are subject to these sorts of urban rumors and speculations brings me back to the idea that there might be a burgeoning comparative literature of mega-construction sites taking shape today, with this particular case representing a strong subgenre: mythic construction worker stories, John Henry-esque figures who single-handedly assemble whole floors of Dubai skyscrapers at midnight, with a cigarette in one hand and a hammer in the other (or so the myths go), as a kind of oral history of the global construction trade; and, finally, 3) there should be some kind of TV show – or a book, or a magazine interview series – similar to Dirty Jobs in which you go around visiting people who live in absurd places – like construction cranes atop the Burj Dubai, or extremely distant lighthouses, or remote drawbridge operation rooms on the south Chinese coast, or the janitorial supply chambers of inner London high-rises – in order to capture what could be called the new infrastructural domesticity: people who go to sleep at night, and brush their teeth, and shave, and change clothes, and shower, inside jungle radar towers for the French foreign legion, or up above the train tracks of Grand Central Station because their shift starts at 3am and they have to stay close to the job.

How do they decorate these spaces, or personalize them, or make them into recognizable homes? It's like a willful misreading of Heidegger as applied to the question of building, dwelling inside, and thinking about modern infrastructure.

I'm reminded of a line from Paul Beaty's new novel, Slumberland. Early in the book he writes, and my jaw dropped: "Sometimes just making yourself at home is revolutionary."

[Image: The Burj Dubai, via Wikipedia]. [Image: The Burj Dubai, via Wikipedia].

In fact, consider this an official book proposal – to Penguin, say: a quick, 210-page look at strange inhabitations, like that guy who lived inside a bridge in Chicago, only not some mindless catalog of quirky stories – like, ahem, that guy who lived inside a bridge in Chicago – but profiles of people with amazingly strange jobs who have to sleep in places no one else would even imagine calling home. Down beneath the streets of Moscow in a subway switching HQ in a little bunkbed. Out on the Distant Early Warning Line of the U.S. Arctic military – where it's just you, a toothbrush, and the Lord of the Rings on DVD. You dream about forests.

Or perhaps there is a suite of individual employee bedrooms in some South Pacific FedEx re-routing warehouse, where long-haul pilots are required by labor law to sleep for ten hours between flights; they come through twice a year, leaving Robert Ludlum paperbacks behind for themselves to read later.

The micro-tactics of dwelling inside strange but temporary homes.

In any case, while I'm working on that, the rest of the Daily Telegraph article is worth a quick read.

(Spotted on Archinect).

|

|

[Image: Professor Igor Panarin's six-fold vision of a disintegrated United States; I love how it will precisely follow today's existing state lines – and that Kentucky will join the European Union].

[Image: Professor Igor Panarin's six-fold vision of a disintegrated United States; I love how it will precisely follow today's existing state lines – and that Kentucky will join the European Union].

[Images: From a short film by

[Images: From a short film by  [Image: A short article about Nic Clear from the March 2008 issue of

[Image: A short article about Nic Clear from the March 2008 issue of

[Images: From a short film by

[Images: From a short film by  [Image: The dark skies above Galloway Forest Park, Scotland, via the

[Image: The dark skies above Galloway Forest Park, Scotland, via the  [Image: The Pleiades, photographed by

[Image: The Pleiades, photographed by

[Images: The "

[Images: The " [Image: Sludge makes itself at home in Harrimann, Tennessee; photo by J. Miles Carey/

[Image: Sludge makes itself at home in Harrimann, Tennessee; photo by J. Miles Carey/ [Image: By Craig Hodgetts, from his prospective drawings for a film adaptation of

[Image: By Craig Hodgetts, from his prospective drawings for a film adaptation of  [Image: London nuked, courtesy of

[Image: London nuked, courtesy of  [Image: Courtesy of

[Image: Courtesy of

[Images: Courtesy of

[Images: Courtesy of  [Image: Courtesy of

[Image: Courtesy of  [Image: Courtesy of

[Image: Courtesy of  [Image: Courtesy of

[Image: Courtesy of  [Image: Courtesy of

[Image: Courtesy of  [Image: Courtesy of

[Image: Courtesy of  Finally, here is what would happen if a nuclear bomb was dropped on a relatively non-urban environment: in this case, the town of Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

Finally, here is what would happen if a nuclear bomb was dropped on a relatively non-urban environment: in this case, the town of Chapel Hill, North Carolina. [Image: Courtesy of

[Image: Courtesy of  "Officials in the western Swedish town came up with the idea," the

"Officials in the western Swedish town came up with the idea," the  [Image: John Constable, Seascape Study with Rain Cloud, 1824].

[Image: John Constable, Seascape Study with Rain Cloud, 1824]. [Image: New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina; photographer unknown].

[Image: New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina; photographer unknown]. [Image: The aquatic aftermath of Hurricane Ike, photographed by Carlos Barria for Reuters; via

[Image: The aquatic aftermath of Hurricane Ike, photographed by Carlos Barria for Reuters; via  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Art by

[Image: Art by  [Image: From Power from the Wind by Palmer Cosslett Putnam].

[Image: From Power from the Wind by Palmer Cosslett Putnam]. [Image: From a project for fish-farming the Thames by Benedetta Gargiulo, part of a recent design studio at the Architectural Association taught by

[Image: From a project for fish-farming the Thames by Benedetta Gargiulo, part of a recent design studio at the Architectural Association taught by  [Image: The subterranean granny flat of the future, via the

[Image: The subterranean granny flat of the future, via the  Last week,

Last week,  The theme for the day is

The theme for the day is  [Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: The

[Image: The