|

|

[Image: From OnSite.12, Bed Supperclub, Bangkok (2009) by Sebastien Wierinck]. [Image: From OnSite.12, Bed Supperclub, Bangkok (2009) by Sebastien Wierinck].Sebastien Wierinck's public furniture projects seem to lend themselves to some interesting misinterpretations. For instance, when I first saw the two projects pictured here I thought not only that they were one project, but that they were the black tentacles of some kind of furniture-laying machine.  [Image: From OnSite.12, Bed Supperclub, Bangkok (2009) by Sebastien Wierinck]. [Image: From OnSite.12, Bed Supperclub, Bangkok (2009) by Sebastien Wierinck].In other words, I thought, a tangle of black tubes suspended from the ceiling would, when needed, come coiling down to take the shape of whatever furniture you desired at the time: a bench, a table, a love seat, perhaps even a rug. When you no longer need that particular chair, bench, or nightstand anymore, the coils would simply rewind upward into a canopy of tubes (or perhaps even be withdraw themselves into a machine somewhere in the center of the room, like what's pictured in the first image, above).  [Image: From OnSite.14, Transmediale, Berlin (2009), by Sebastien Wierinck]. [Image: From OnSite.14, Transmediale, Berlin (2009), by Sebastien Wierinck].After a long day at work, then, you would walk into your house – which has no permanent furniture – and you'd see a shimmering mass of black tubes swaying in a slight evening breeze above your head. You'd push several buttons, and the system would begin to move, drooping down in long loops and turning back and forth in tight corners and curves, all laying out the forms of temporary furniture – bed, table – as you get ready for a quiet night at home.  [Image: From OnSite.14, Transmediale, Berlin (2009), by Sebastien Wierinck]. [Image: From OnSite.14, Transmediale, Berlin (2009), by Sebastien Wierinck].Of course, this admittedly somewhat willful misinterpretation of the evidence at hand is not entirely wrong: after all, though Wierinck's pieces don't uncoil from the ceilings in ad hoc patterns, forming zones of temporary furniture throughout empty interiors, they are meant to be (literally) flexible, (somewhat) mobile, and easy enough to reprogram for other spaces. But what a beautiful thought: that you could walk into an empty room, hit a few buttons, and then watch as custom, temporary furniture is 3D-printed into the space all around you. Like a strange rain coming down from the ceiling, or the materialization of a dream, usable shapes gradually form – and then you sit, book in hand. On demand, from above. (Spotted on SpaceInvading).

[Image: All systems go... Original photo by Jim Grossman, courtesy of NASA]. [Image: All systems go... Original photo by Jim Grossman, courtesy of NASA].This is just a quick note to get the word out, but I'm falling out of my chair excited to announce that The BLDGBLOG Book – which is finally shipping throughout the English-speaking world, it seems, with people emailing from Australia, Canada, the UK, and the United States to say that their books have arrived – will officially go live on Tuesday, July 7, with a two-hour launch party hosted by the Architectural Association and sponsored by Wired UK. Here are the details: Plus special guest(s) to be announced! And here's a map. The basic gist of the evening is to show up, grab a drink at the AA bar (they serve Leffe, one of my favorite beers), take a look at some of the awesome student projects that will be on display that night throughout the building as part of the AA's year-end exhibition (so bring a notebook! there will be cool ideas all over the place and students who deserve the attention), and then wander downstairs to the bookshop and dining area, in the basement, where the "launch" itself will take place. So come by, have a drink, talk to people, flip through the book, purchase a copy from the AA bookshop, get it signed, do whatever it is that you want with it – enjoy the images, read the interviews, rest your beer on it, show it to people – and just sort of hang out till 8pm or so, when it all comes to a close. It's not formal, and it's not a lecture. If the weather's nice, you can even step outside and enjoy the blue skies of Bedford Square. Meanwhile, I owe a gigantic thanks to Brett Steele, director of the AA, for hosting this event and Thrilling Wonder Stories last month; to Ben Hammersley, associate editor of Wired UK, for his own interest in all things BLDGBLOG and for bringing me on board last month as contributing editor at the magazine; and to Liam Young, who was absolutely instrumental in seeing these plans come together. Hope to see you there – and expect a very long post next week about The BLDGBLOG Book itself, which I'm excited to introduce to everyone, finally, now that is has officially hit the shelves.

[Image: Photo of the Atlantic Avenue train tunnel taken by Joshua Lott for The New York Times; see below for more information]. [Image: Photo of the Atlantic Avenue train tunnel taken by Joshua Lott for The New York Times; see below for more information].In the interest of cleaning out a long file of recommended links, here's a quick list of stories that I've otherwise missed: —Two brothers in Louisiana are ridding their property of 40-year old levees: "In what experts are calling the biggest levee-busting operation ever in North America, the brothers plan to return the muddy river to its ancient floodplain, coaxing back plants and animals that flourished there when President Thomas Jefferson first had the land surveyed in 1804." —"Flu pandemics may lurk in frozen lakes," Wired Science warns. "The next flu pandemic may be hibernating in an Arctic glacier or frozen Siberian lake, waiting for rising temperatures to set it free. Then birds can deliver it back to civilization." I'm reminded here of the novel Cold Plague by Daniel Kalla, which I somewhat inexplicably read on a plane ride from New York to San Francisco this spring; the book's story goes that a bottled water company has begun to ship and sell drinking water pumped from Antarctica's subglacial Lake Vostok – a lake briefly mentioned in BLDGBLOG's earlier interview with Kim Stanley Robinson – only to discover that a prion is in the water, causing irreparable brain damage and eventual death in everyone who drinks it... In any case, the Wired Science article quotes a scientist who "thinks migrating waterfowl regularly deliver influenza viruses to Arctic glaciers and lakes, where it becomes frozen in ice. When the ice melts, birds pick the virus up and transport it back south where it can infect humans." Amazing. Nature's secret virus cycles. —While we're on the subject of ice, check out this brief video shot inside the tunnels beneath Greenland's melting ice sheet: "Unique video footage taken hundreds of metres inside the ice has revealed a complex subglacial network of interconnecting tunnels that carry water from the surface to deep inside the ice sheet," we read in the Guardian. These tunnels, however, are one of the primary threats to the very existence of the ice sheet, lubricating the glacier's accelerating slippage off of Greenland's rocky base. —Two cool links from Noah Shachtman's Danger Room: " Military Scientists Explore Planet Hacking" (also see the climate change chapter of the The BLDGBLOG Book for more) and " Scientist Looks to Weaponize Ball Lightning" (perhaps the future of global warfare will look not unlike medieval sorcery, hurling lightning at one another from desert mountaintops).  [Image: Lightning storm over Boston, ca. 1967; photo courtesy of NOAA's NOAA's National Weather Service Collection]. [Image: Lightning storm over Boston, ca. 1967; photo courtesy of NOAA's NOAA's National Weather Service Collection].—Adventures in applied acoustics: according to a short article in Mother Jones, "Dangerous red tides that kill fish and marine mammals and are toxic, even carcinogenic, to humans, might be destroyed using bursts of ultrasound." Audio warfare installations lining the Gulf Coast will vibrate red tides out of existence. —Krispy Kreme doughnuts – which I was shocked to see all over Melbourne, Australia, on my visit last month – aren't just bad for your arteries: "doughnut grease and other waste from a plant in Lorton have clogged up the county's sewage system, causing $2 million in damage." In fact, "The muck got so bad that a nearby pumping station began reeking of doughnuts, and a camera inserted into one of the pipes 'got stuck in the grease, preventing inspection of the remainder of the line'." The Lorton mentioned here is Lorton, Virginia – but I suspect they'll start seeing the same problems Down Under... —Finally, many people will already know the story behind the discovery, in 1980, of the Atlantic Avenue train tunnel in Brooklyn, an underground viaduct that had otherwise lain abandoned beneath the city. If you don't know it, the story is awesome. Now, however, Bob Diamond, the man who discovered the tunnel, believes that there's yet more down there to find: "Behind a wall in the tunnel, near Atlantic Avenue and Hicks Street, he believes, there is a steam locomotive lying on its side like an abandoned toy train, in 'pristine condition, a virtual time capsule.' And he wants to dig it up." I absolutely love the idea of exhuming buried machines from the surface of the city. I'm tangentially reminded of the bizarre story of the Air Loom Gang – in which an "influencing machine" controlled by British Parliament was accused of exerting mind control upon the citizenry – only re-imagining that story today, with a kind of modernday James Tilly Matthews convinced that the buried enginery of the city around him has begun to influence the thoughts of all the people he knows... He descends into the tunnels and basements of the city, armed with ground-penetrating radar, performing magnetic archaeology on every wall and floor, detecting the hulking, Lovecraftian shapes of machines whose existence other people so vehemently deny. In any case, I'm thrilled by the idea that, somewhere beneath your own apartment complex, in the stratigraphic euphoria of the city, there might be an abandoned train – in fact, there's an earlier post here on BLDGBLOG about something remarkably similar. (Links via delicious.com/bfunk, delicious.com/rgreco, delicious.com/javierarbona, and Steve Silberman. Previous Quick Lists: 11, X, 9, 8, etc. etc.).

It's hard for me to read stories about human origins without feeling like there's some kind of agenda at work, buried just beneath the surface. Modern humans are not African at all, the Piltdown hoax would have had us believe; our ancestors, lost to deep time, were in fact properly English, an anthropological pseudo-discovery that came just in time, its advocates hoped, to help save the British Empire's reputation... or at least to boost a few specific careers. Nonetheless, I'm something of an addict for stories about human origins.  [Image: A portrait of the Piltdown forgery in action, by John Cooke (1915); Richard Fortey's recent book Dry Storeroom No. 1 has a great chapter on Piltdown]. [Image: A portrait of the Piltdown forgery in action, by John Cooke (1915); Richard Fortey's recent book Dry Storeroom No. 1 has a great chapter on Piltdown].Caught up in all of this are the fantasies of belonging that different origin stories allow us to project upon the present. For instance, if you feel at home in the grasslands of South Dakota, can you say it's because you are "from" the plains of Africa? Or, if you love living in the American southwest, is it because humans really originated in the desert valleys of the Middle East? You're simply sensing that deeper attachment? In this context, the eroded riverine landscape of Olduvai Gorge has become something of the ultimate origin point for all of us, giving geological form to an idea so extraordinarily abstract (our very origins as living creatures) that its value is at least as much rhetorical as it is scientific. I mention all this, though, because an article published earlier this month in New Scientist suggested that modern humankind's primordial African ancestors might themselves have been immigrants – having walked south after a much earlier and, until now, undocumented evolutionary appearance in Europe. Referred to casually as an "into Africa" scenario – as opposed to an "out of Africa" one – this would mean that "our ancestors lived in Europe and only later migrated to Africa, where modern humans are thought to have evolved." Europe, in this model, is the origin, Olduvai Gorge a mere inn along the way. I don't mean to overplay the possible political interpretations here – although I do want to say again that I simply cannot read stories like this without wondering what might be at stake in the acceptance of their conclusions, and if there isn't a certain amount of wish-fulfillment going on ( finally, Europe is the center once again!) – but do check out the original short article for more. At the very least, it's worth asking what might happen if we do make it all the way down to the very point of human origin – to that germinal site of all future reference and emanation – only to discover that it's a meaningless detour. Beneath the foundations, are there always deeper foundations? (Also on BLDGBLOG: Early Man Site).

For $200,000 a year, guaranteed for 20 years, totaling no less than $4 million, you could have the second-busiest subway station in Brooklyn named after you... or your product. This station, "the nexus of subway stops at Atlantic Avenue, Pacific Street and Flatbush Avenue in Downtown Brooklyn," we read in The New York Times, is about to be sold, however, to Barclays, becoming Barclays Station. “They can call it anything they want, as long as my train’s on time,” one regular commuter quips – but to what extent is that really true?  [Image: The Chrysler Building – a sponsored building – montaged by Flickr-user Chalky Lives]. [Image: The Chrysler Building – a sponsored building – montaged by Flickr-user Chalky Lives].For instance, the same article cites several rejected proposals for the renaming of urban infrastructure – but $4 million is not, in many contexts, even a very large sum of money. Super Bowl ads famously cost as much as $6 million dollars a minute – in which case $4 million for twenty years' worth of public exposure is almost absurdly underpriced. In fact, the average marketing budget of a Hollywood blockbuster could quite easily absorb the cost of renaming a minor New York City subway station for the next decade – well into that film's second life of digital sales, that is – and, to use another example, buildings are still known as, say, the Die Hard Building twenty years after the fact, even if they were never official renamed. Somewhat bizarrely, for instance, I read literally just today that screenwriter Joe Eszterhas was paid $3 million, in 1992 dollars, for writing Basic Instinct – but he could simply have had a Manhattan subway station named after him. Eszterhas Central. Perhaps Shia LaBeouf should forego monetary payment altogether for the next Indiana Jones film – and get a new freeway in Los Angeles named after him. In any case, as private sponsorship of public space becomes the urban norm, will we see acts of infrastructure becoming little more than spatially immersive forms of corporate advertisement? If a Stephen King novel coming out next year had a small bridge in Maine named after it – for the next twenty years – the It 2 Bridge – surely this would not be a bad way to give King's novel near-permanent cultural exposure? Put another way, why buy one minute of Super Bowl time when you could buy twenty years' worth of high-density urban exposure, associating a certain sidewalk, bridge, museum, or subway station with you and/or your product? I'm reminded of the recent news that Kentucky Fried Chicken had branded paving installed atop Louisville potholes – fixing the city's broken streets even while reminding everyone who lived there where they could buy fried breast meat. Jason Kottke points out, after all, that institutions such as Rockefeller Center and Columbia University are also sponsored, in the literal sense that their names were allocated way back when based on who supplied the money. The Chrysler Building is another obvious example. In the end, then, if you went to work each day boarding the subway at Terminator Salvation Station, surely at least for someone born today, taking that commute in twenty years' time wouldn't even seem that strange? Sponsor a tectonic plate. Sponsor a moment in time. Sponsor fifteen minutes of foreign bombing: "Aid raids over Afghanistan today were brought to you by Target™..." When will urban or national infrastructure simply become another form of advertisement? Perhaps it won't even be long before we start sponsoring lifeforms – newly discovered rain forest birds named after a Latinized version of Bayer, or entire new microorganisms engineered from scratch in university labs, named after the next film from Pixar. (Via @nicolatwilley and kottke.org).

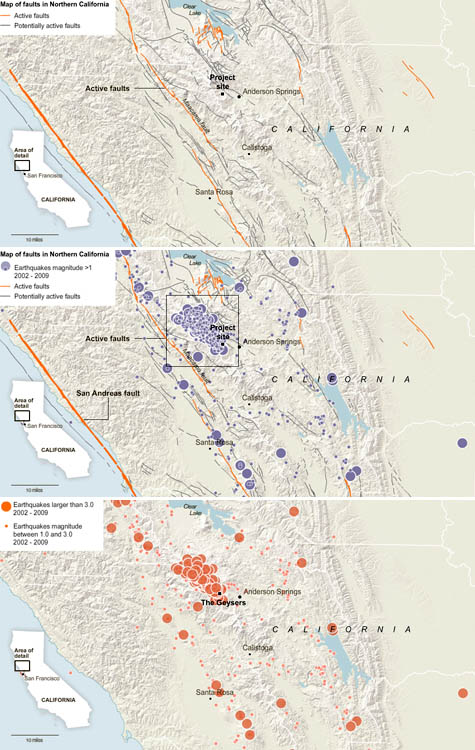

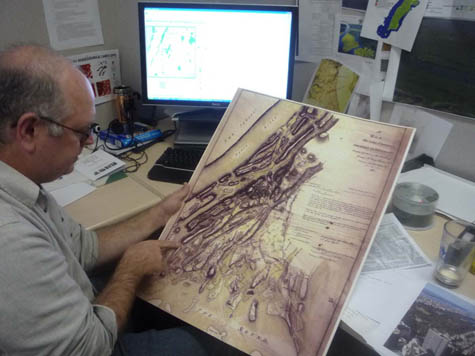

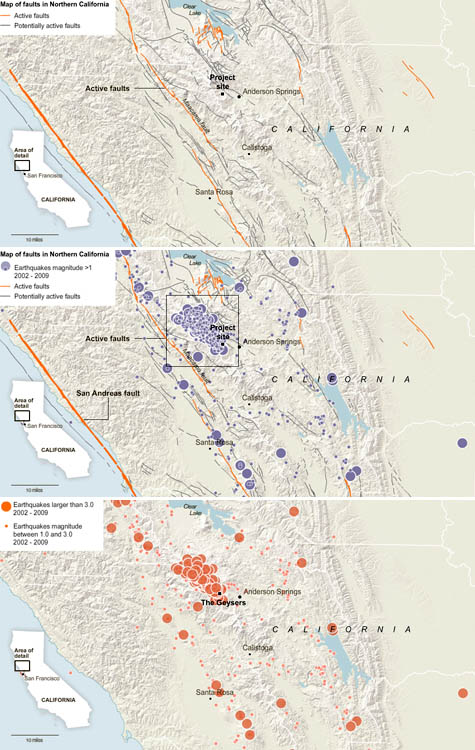

Artificial earthquakes triggered by deep-crust drilling operations have always been of interest here, and The New York Times brings the idea back into the media cycle today with a new article – complete with a sidebar titled "The Danger of Digging Deeper." Don't miss the interactive graphic.  [Images: Geothermal projects and earthquake clusters in northern California; graphics by Hannah Fairfield, Xaquín G.V., James Glanz, and Erin Aigner for The New York Times]. [Images: Geothermal projects and earthquake clusters in northern California; graphics by Hannah Fairfield, Xaquín G.V., James Glanz, and Erin Aigner for The New York Times].So the scene this time is the countryside two hours north of San Francisco, with a company called AltaRock. "Residents of the region, which straddles Lake and Sonoma Counties," we read, "have already been protesting swarms of smaller earthquakes set off by a less geologically invasive set of energy projects there. AltaRock officials said that they chose the spot in part because the history of mostly small quakes reassured them that the risks were limited." Serious seismic problems arise when you begin to tap into – and then break through – very deep rocks. The reference case for The New York Times here is something that happened in Basel, Switzerland, back in 2006 (a seismic event mentioned briefly in The BLDGBLOG Book). The specific drilling technique used in Basel, we read, was one that "created earthquakes because it requires injecting water at great pressure down drilled holes to fracture the deep bedrock." The opening of each fracture is, literally, a tiny earthquake in which subterranean stresses rip apart a weak vein, crack or fault in the rock. The high-pressure water can be thought of loosely as a lubricant that makes it easier for those forces to slide the earth along the weak points, creating a web or network of fractures. A very similar technique, however, will soon be put into widespread use in northern California. There, in the foggy hills and forests, AltaRock "has received its permit from the federal Bureau of Land Management to drill its first hole on land leased to the Northern California Power Agency, but still awaits a second permit to fracture rock." One resident awesomely points out: “If they were creating tornadoes, they would be shut down immediately. But because it’s under the ground, where you can’t see it, and somewhat conjectural, they keep doing it.” Artificial tornadoes! The U.S. wind industry should take note.  [Image: Artificial terrain rises from below... A screenshot from Fracture by LucasArts]. [Image: Artificial terrain rises from below... A screenshot from Fracture by LucasArts]. In many ways, I'm reminded of the game Fracture by LucasArts, in which " terrain deformation" is deployed as a central part of gameplay. You use weapons like Tectonic Grenades to generate new and temporary, but militarily significant, geographic features: hills, valleys, moraines. Putting these two stories together, though, perhaps an interesting plot emerges... You find yourself driving north out of San Francisco one fall, hoping to do some hiking – but the further north you go, the more you notice slight tremors. Every few minutes, there's an earthquake – and some of them are rather large. Soon, things start to look unfamiliar. You thought you knew this landscape from previous travels, but it no longer looks quite right. There are hills where you don't remember hills being. The road itself, freshly paved and by all indication brand new, weaves and winds around lulls and rises that aren't marked on the map – and the map was printed six months ago. Finally, you reach your hotel around nightfall, only to experience another set of small earthquakes shake the ground. The clerk laughs as you try to sign for your room, because your signature comes out all wobbly as another temblor strikes. Your suitcase falls over. "Am I gonna get any sleep tonight?" you ask, trying to play it funny. But then, at 7am the next morning, your investigations begin... Turns out, in a geologically-themed science fiction film directed by Roger Donaldson, from a screenplay by BLDGBLOG, that deep drilling operations by a foreign geothermal consortium have been "unlocking" certain well-faulted portions of subsurface bedrock; huge masses within the earth's surface then rise or fall, slipping sometimes quite quickly, thus drastically altering the visible landscape... and causing thousands of earthquakes each year. The surface of the earth is being rearranged from below. In any case, check out the New York Times for more. (Thanks to Nicola Twilley for the tip!)

An article by Sebastian Rotella in the L.A. Times this past weekend presented readers with an interesting example of what might be called infrastructural interpretation.  [Image: Photo by ohhector, available through a Creative Commons license]. [Image: Photo by ohhector, available through a Creative Commons license].On the one hand, Rotella suggests a fascinating way to explore the spatial role of the European train station in 20th century political thrillers. Citing the novels of Eric Ambler, Graham Greene, and John Buchan, and referencing early Alfred Hitchcock films, Rotella demonstrates how it might be possible to foreground certain architectural forms – the train shed, or, perhaps, the multistory car park, the highway flyover, or the maximum security prison – in the process of writing cultural histories. A short history of novels partially set inside planetariums. A spatial history of films set in shopping malls... with an introduction by Zach Snyder. In this case, of course, it'd be a political microhistory of the European train station – and someone could very easily get a PhD out of such a scenario: The Train Shed as Depicted in Film, Games, and Literature: An Architecture of Encounter. But the second point of interest here for me is more political. And that's the fact that, for something published in the United States – and in Los Angeles, no less, kingdom of the private automobile – the article exhibits a depressingly obvious distrust in the municipal spaces of public transport. In other words, the article goes on to describe the European train station – and train travel more generally – as a threatening bastion of non-white otherness that has infiltrated the modern city. Moroccans, after all, live near certain train stations... and Muslims sometimes ride those very trains... "Moreover," Rotella points out, "train stations tend to be in working-class immigrant areas where desperadoes find shelter, weapons, false documents and other tools of the trade. The Gare du Midi, on the southern edge of downtown Brussels, is a good example. A few Spanish and Italian shops remain from previous migrations, but the personality of the neighborhood today is Moroccan and Turkish." Indeed, Rotella further suggests, that otherwise unthreatening train station near you might even serve as spatial host to a "leftist-Islamic militant alliance" – never mind the fact that Islamic terror is almost universally committed against traditional leftist political goals (whether this refers to the separation of church and state or to gay rights and female suffrage). But Al-Qaeda, in this way of interpreting European train infrastructure, is something like the passenger from hell – Islamic militarism riding amok, exploding bombs on high-speed routes and "slaughtering" innocent bystanders.  [Image: It's Terror Train. In the future they might even serve couscous]. [Image: It's Terror Train. In the future they might even serve couscous]."Trains, stations and the gritty neighborhoods that surround them are often the backdrop to danger," Rotella warns. Specifically, "trains and their stations have played a key role in modern-day plotting and attacks by Islamic terrorists." Of course, Mike Davis's recent history of car bombs might offer a slightly different take on the relative dangers of various transport infrastructures – but I digress. This would never happen in the United States, the subtext of Rotella's argument seems to suggest, and it never will... provided we never build more public train stations. In this context, President Barack Hussein Obama's tentative interest in funding an American high-speed train network takes on rather spectacular political implications – at least as long as one lives in fear of a "leftist-Islamic militant alliance" being forged amongst the screaming wheels of modern railroad yards. Osama bin Laden is alive and well... and securing more funding for Amtrak. One man, we actually read – a man accustomed to train travel and with a penchant for political violence – "drank tea and ate couscous while allegedly hatching multimillion-dollar holdups, arms deals, money-laundering schemes and terrorist plots." He ate couscous "in the kebab joints" near Belgium's Gare du Midi, and he daydreamed scenes of near-supernatural violence. He would arrive upon the world stage, enshrouded in robes of blood. In any case, I don't mean to sound over-eager to ridicule this story; after all, train stations are heavily populated sites of public gathering, and thus very effective targets for terrorist plots. But does this also make them terrorist breeding grounds? Can train stations really represent both the secular invasiveness of big-government bureaucracy and violently independent religious conservativism? Rotella's implication here – that all train stations are somehow, in and of themselves, infrastructural acts of invitation to a vampiric immigrant presence that secretly hopes to inflict evil, thus equating train travel with international Islamic terrorism – seems very obviously motivated by ideology, not intellectual clarity or rational analysis. Which is too bad, because a cultural history of the train station – as a site for political intrigue and so on – actually sounds incredibly interesting to me. At the very least, one could start a Wikipedia page for "political plots hatched in train stations," or "murders committed in parking garages," or "bombed shopping malls" – focusing on the infrastructural spaces within which certain major types of crime have been planned or committed. Even more specifically, is there a spatial taxonomy for spy stories – and what types of structures seem repeatedly to appear? Alas, Rotella's article seems too besotted with AAA to view train travel as anything but a threat to national security.

Note: This is a guest post by Nicola Twilley.Every tree is a living archive, its rings a record of rainfall, temperature, atmosphere, fire, volcanic eruption, and even solar activity. These arboreal archives together reach back in time over centuries, sometimes millennia. We can even map human history through them—and onto them—tracing famines, plagues, and the passing of our own lives.  [Image: A scene from Alfred Hitchcock's film Vertigo, with Jimmy Stewart and Kim Novak in Muir Woods, outside San Francisco, where Novak points to the concentric rings of the redwood trunk and says, "Here I was born... and here I died"]. [Image: A scene from Alfred Hitchcock's film Vertigo, with Jimmy Stewart and Kim Novak in Muir Woods, outside San Francisco, where Novak points to the concentric rings of the redwood trunk and says, "Here I was born... and here I died"]. For artist Katie Holten, trees were thus the natural starting point for an oral history of a city street in the Bronx. To mark the 100th anniversary of the Grand Concourse, a four-mile-long boulevard that connects Manhattan to the parks of the Northern Bronx, Holten has created the Tree Museum: 100 specially-chosen trees between 138th Street and Mosholu Parkway, each of which has a story to tell if you dial the number at its base. The museum opens today, June 21, with a parade and street fair: for those of us not in New York, a podcast and brochure will be available for download, and you also can view each of the tree locations on Google Maps.  [Image: Trees in the museum each have their own sidewalk marker, which gives their name and extension number]. [Image: Trees in the museum each have their own sidewalk marker, which gives their name and extension number].Only a handful of the one hundred "story-trees" date from the Concourse's construction, when an avenue of Norwegian maples was planted to shade carriages and pedestrians strolling along the broad boulevard. In an email conversation, Holten explained to BLDGBLOG that most of these original trees were moved to Pelham Bay Park when the B/D subway line was built in the early '30s. Twelve of the surviving maples are joined in the Tree Museum by representatives of fifty-nine other tree species, from an Amur Corktree in Joyce Kilmer park to a Kentucky Coffeetree just south of Tremont Avenue. In fact, each tree is carefully identified by its species name, in Spanish, English, and Latin, to draw museum visitors' attention to their variety. Holten told me that, early on in her community outreach, she realized how important naming the trees would be when a teacher in a local school confessed, incredibly, that it was only after he heard about the Tree Museum idea that "he noticed the next time he was walking that there were different kinds of trees. Before that he'd thought they were just 'trees'."  [Image: A section of the Tree Museum map; a much larger version can be seen here]. [Image: A section of the Tree Museum map; a much larger version can be seen here].The trees were chosen for their variety, Holten says, but also for "location, age, and connection to a particular person or story." Holten acted as matchmaker, pairing trees with former and current Bronx residents, as well as scientists, authors, and activists who have worked in the area. Among the 100 participants are well-known former Bronxites DJ Jazzy Jay and Daniel Libeskind, students at the Bronx Writing Academy, and Jonathan Pywell, Bronx Senior Forester, who helped Holten identify all the trees (not an easy task in mid-winter). Each has used their tree as the starting point for a personal anecdote, snippet of neighborhood history, song, or even a digital sound recording. Taken together, the tree stories are part shared history, part personal memory, part science lesson—they form what Holten describes as "the whole ecosystem of the street."  [Image: A computer-generated image of Klaus Lackner's prototype "synthetic tree," which would remove carbon dioxide directly from the air; image courtesy of Columbia University]. [Image: A computer-generated image of Klaus Lackner's prototype "synthetic tree," which would remove carbon dioxide directly from the air; image courtesy of Columbia University].In her email, Holten went into some detail describing the range of stories you can hear as you dial each tree's extension, from the sound of a Puerto Rican tree frog (No.73, a Gingko) to a local preservationist describing how he fought to turn an abandoned lot into the park that now surrounds No. 100, a Cottonwood. From her email: Klaus Lackner (professor in the Department of Earth and Environmental Engineering at Columbia University and director of the Lenfest Center for Sustainable Energy) tells the story of the carbon cycle and his attempt to create a "fake plastic tree," or air extractor, that would suck the CO2 out of the air and convert it into something we can put in a safe place. Eric Sanderson (a landscape ecologist based at the Bronx Zoo, and author of Mannahatta) needed a really old, native tree to talk about projecting the landscape backwards. I gave him No. 9, a beautiful American Elm outside Cardinal Hayes High School.

At the northern end of the Concourse, at 206th St, there's a huge chunk of rock between two buildings; it's like the side of a cliff. I had to give the tree there, No. 95, to Sid Horenstein, a geologist who recently retired from the American Museum of Natural History. He's able to use the rock outcrop to explain the story of what the Concourse lies above—it was built on a ridge and that's one of the main reasons the street was constructed here, because it was elevated and offered spectacular views of the countryside all around.

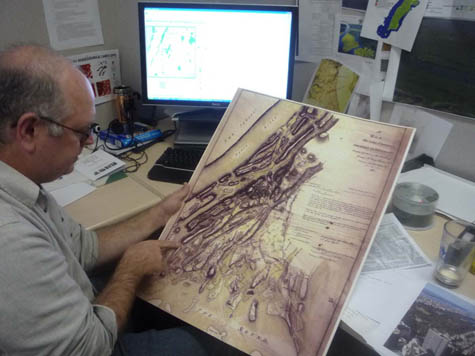

And Tree No. 45, a Little Leaf Linden, has a story told by Patricia Foody, a 95-year-old Bronxite. She remembers her dad bringing her for a walk to the Concourse to visit his brother's tree in just this location—it was one of the original maples, and many of them had plaques for soldiers who had died in World War I. Some of the stories come from people who work with the trees directly: Jennifer Greenfeld, director of Street Tree Planting for the Parks and Recreation department, uses No. 66, a Chinese Elm, to provide an overview of street trees throughout New York City and the policy battles they sometimes cause. Barbara Barnes, a landscape architect also with the Parks department, puts her tree in the context of the historic street tree canopy project she's working on, to replant Joyce Kilmer and Franz Sigel parks as they were originally laid out.  [Image: Eric Sanderson pointing at a map of the Bronx; photo by Katie Holten]. [Image: Eric Sanderson pointing at a map of the Bronx; photo by Katie Holten].For other participants, the trees function as more of a backdrop for personal history and community activism. Sabrina Cardenales is the real-life model for the character Mercedes in Adrian Nicole LeBlanc's Random Family: Love, Drugs, Trouble, and Coming of Age in the Bronx, which documents extreme urban poverty in New York: both Sabrina and Adrian introduce themselves and read a passage from the book as part of the Tree Museum. Meanwhile, Majora Carter, an environmental justice activist and MacArthur fellow from the south Bronx, uses tree No. 6, a honey locust, to tell people: "You don't have to leave your neighborhood to live in a better one, and trees are an important part of making that happen." The variety of voices and stories Holten describes accumulate into a sense that plenty of people really do care about these trees, this street, and the Bronx in general. They also act as a series of nudges to look at the urban landscape in a new light. The result is that the Tree Museum, at least in theory, will recreate some of the optimism of the Grand Concourse's roots in the City Beautiful movement, while not glossing over the struggles and setbacks faced by the "Champs-Élysées of the Bronx" ever since.  [Image: The Bronx Grand Concourse, looking north from 161st Street; photo by Katie Holten]. [Image: The Bronx Grand Concourse, looking north from 161st Street; photo by Katie Holten]. As part of the Concourse's centenary celebrations, the Bronx Museum and New York's Design Trust For Public Space are running a competition called Intersections: Grand Concourse Beyond 100, to gather new proposals for regenerating the street. Although the call for entries period is now closed, Katie Holten has set up a community forum for the Tree Museum, and clearly hopes the project will prompt action, as well as reflection. Holten explains her most basic hope, which is that the Museum will encourage people to start using and enjoying their shared public space again: One hundred years ago the Concourse was built for people to stroll along, under the shade of the trees, but in 2009 it takes quite an effort to get people out for a walk—hopefully we’ll get them strolling! There are a number of individuals who I met because they are interested in trees, or in "green" issues, and we've tried to use the momentum of the Tree Museum to help them make differences. For example, Fernando Tirado (tree No. 88) is district manager for Bronx Community Board #7 and he's been prompted to establish a "Greening the Concourse" project. He's organizing summer internships for youth in the area: giving them a job and training, and at the same time actually greening the street. Perhaps more importantly, Holten's Tree Museum (which she describes as "practically invisible—it's part of the urban fabric") demonstrates an intriguing way to re-imagine the landscape: finding ways to make the hidden layers and connections of a street's story visible (or audible) might ultimately be as, if not more, important than installing a new swing set in the park. [Previous guest posts by Nicola Twilley include Watershed Down, The Water Menu, Atmospheric Intoxication, and Park Stories].

Note: This is a guest post by Nicola Twilley.As Geoff mentioned last month, London's Building Center hosted a daylong seminar at the end of May called London Yields: Getting Urban Agriculture off the Ground.  [Image: From London Yields: Urban Agriculture]. [Image: From London Yields: Urban Agriculture].The speakers covered a lot of terrain—so, instead of a full recap of the event, the following list simply explores some of the broader ideas, responses, and questions about urban agriculture that stood out from the day's presentations. 1. Becoming public policyThe event was introduced and moderated by David Barrie, a sustainable development consultant, who framed the day as a collective opportunity to brainstorm ways in which urban agriculture could be moved from mere "sustainable accessory" to become a standard practice of both everyday life and city design. Interestingly, Mark Brearley, Head of Design at Design for London (DfL) and the day's first speaker, provided confirmation of Barrie's diagnosis, confessing that food production was a recent add-on to many of their open space projects. Why? "Because people were asking us about it," he said. Brearley's presentation was an overview of DfL's hundreds of urban regeneration and infrastructure improvement projects; these are, in themselves, interesting but, in aggregate, somewhat exhausting. However, as an office of the London Development Agency, working on behalf of the Mayor of London, Brearley was able to provide a fascinating insight into some of the current institutional priorities that need to be satisfied before urban agriculture can become a standard part of London public policy. For example, DfL's main interest in food production today is in terms of its "public engagement potential" and their primary stumbling block is how to measure the scaleability of local initiatives. Any London-based urban agriculture projects hoping for a mayoral blessing, take note! 2. Food is a design toolThe second speaker was Carolyn Steel, author of the excellent book Hungry City: How Food Shapes Our Lives. Hungry City traces how food has shaped both the city and its productive hinterland throughout history, from the Sumerian city of Ur to today's London via the markets and gates of ancient Rome. Steel provides a wide-ranging historical look of food production, importation, regulation, and culture, before putting forward her own intriguing and potentially revolutionary proposition: what would happen if we consciously used food as a design tool to create a "sitopic" city? Steel's coinage here, sitopia—from "sitos" (food) and "topos" (place)—is derived from her realization that "food shares with utopia the quality of being cross-disciplinary... capable of transforming not just landscapes, but political structures, public spaces, social relationships, [and] cities." And because "food is necessary," a sitopian city (unlike its utopian cousin) would remain tied to reality and of universal relevance. The quotations above come from Steel's book, however, rather than her lecture; twenty-five minutes was enough time to provide fascinating examples of food's role in shaping cities and urban life, but, sadly, not enough to explain (let alone explore) further thoughts about food's use as an urban planning tool. More to come soon, I hope, on this topic...  [Image: Ebenezer Howard's original scheme for the Garden Cities of To-morrow shows a landscape reimagined in terms of food production and supply. As Carolyn Steel explains in her own book Hungry City, Howard's plans relied on land reform that was never carried out, and the garden cities of today (Letchworth, Welwyn, etc.) are, as a result, little more than green dormitory suburbs]. [Image: Ebenezer Howard's original scheme for the Garden Cities of To-morrow shows a landscape reimagined in terms of food production and supply. As Carolyn Steel explains in her own book Hungry City, Howard's plans relied on land reform that was never carried out, and the garden cities of today (Letchworth, Welwyn, etc.) are, as a result, little more than green dormitory suburbs].3. Partnerships as infrastructureAnna Terzi, who runs London Food Link's small grants scheme for Sustain, was the day's third speaker; she described one of their current projects, demonstrating how key insights from both Mark Brearley's and Carolyn Steel's talks might look in action. Sustain (a nonprofit alliance for better food and farming) is currently poised to create borough-wide institutional change by partnering with Camden Council and Camden Primary Care Trust (part of the National Health Service). This alliance—with its intriguing implication that the National Health Service might be the one institution with the most to gain by promoting urban agriculture—speaks to the impact of creating new interest groups for locally grown food. By partnering with institutions responsible for dealing with established urban challenges—issues such as public health, economic growth, community engagement, waste, and environmental sustainability—groups like Sustain have the potential to take urban agriculture from decorative hobby to investment-worthy infrastructure. The Camden partnership's report (still in draft stage) aims to outline a relatively coherent and holistic food program for the borough—a plan that promises to use food to reshape at least this part of the city, in terms of promoting social enterprise, meeting infrastructure needs, and reducing health inequalities.  [Image: A lemon grown in Dulwich; photograph by Jonathan Gales (2008), ©Bohn & Viljoen Architects]. [Image: A lemon grown in Dulwich; photograph by Jonathan Gales (2008), ©Bohn & Viljoen Architects].4. Mapping and visualization toolsThe last two presentations of the day agreed that successfully producing food in the city requires a detailed resource inventory combined with effective promotion efforts. Mikey Tomkins, a PhD candidate at the University of Brighton, described systematically mapping the rooftops, grass patches, vertical faces, and vacant lots of Elephant & Castle—whereupon he discovered that 30% of the area's food needs could be met through the cultivation of found space alone. Architects Katrin Bohn and Andre Viljoen, creators of the uninspiringly named CPUL (Continuous Productive Urban Landscapes), emphasized the need to think about spare inventory in terms of population and three dimensionality (their Urban Agriculture Curtain filled a display window one floor above us). Their research techniques included the accumulation of census data and questionnaires combined with GPS mapping and site visits in order to analyze a landscape's food production capacity. Both Tomkins and Bohn & Viljoen also showed several projects intended to help people read the city in terms of food, using tools as diverse as "edible maps" of London and visual analyses of urban agriculture in Havana, to installations and public events, such as the Continuous Picnic. This was a day-long event, part of the 2008 London Festival of Architecture, that included an "Inverted Market" (bring your own locally grown fruit and vegetables to be admired, judged, and then prepared), as well lessons in "Community Composting"; a giant public picnic then spread throughout Russell Square and Montague Place, with connecting corridors between. Meanwhile, for his Edible Maps series, an example of which appears below, Tomkins targets a new type of urban resident: the "food-flâneur," who, map in hand, "could start to picture... the grassed areas around housing, the corners of parks, or the many flat rooftops of this quarter of Croydon spring into life with psychogeographic food." Another example of urban agriculture as an opportunity for community activation was Croydon Roof Divercity, Tomkins's collaboration with AOC (previously discussed, along with other AOC projects, on BLDGBLOG here).  [Image: From Mikey Tomkins's series of Edible Maps, this guide represents the area around Surrey Street car park, site of Croydon Roof Divercity, in terms of inventory and potential yield]. [Image: From Mikey Tomkins's series of Edible Maps, this guide represents the area around Surrey Street car park, site of Croydon Roof Divercity, in terms of inventory and potential yield].5. Easy, cheap, and somewhat under controlBoth Anna Terzi and Bohn & Viljoen recognized the difficulty of maintaining urban agriculture projects, once the initial novelty has worn off. Bohn & Viljoen are currently working on a twelve-step program to prevent relapse, while Sustain are offering ongoing practical and financial support to new food growing spaces in London through their Capital Growth initiative. Throughout the morning, David Barrie repeatedly registered his concern that urban agriculture needed to be economically viable, not just an upscale $64 Tomato lifestyle choice. Several of the presenters added a layer of nuance to Barrie's formulation, noting that cheap food has simply had its costs externalized and hidden (Carolyn Steel) and that organizations like the New Economics Foundation are developing the much-needed tools to measure urban-agriculture-created value, such as increased community engagement and environmental sustainability, which is currently perceived as intangible and qualitative (Katrin Bohn). Mikey Tomkins argued against an economics-based one-size-fits-all approach to urban agriculture, explaining that the scale of a food growing project determines its possible benefits. Thus differentiated, food gardening generates educational and quality of life outcomes and should be measured accordingly, while market gardening creates recycling benefits, and urban agriculture can be evaluated in terms of yield. Finally, the elephant in the room was the degree of coordination and regulation needed to transform London into a food-producing landscape. In an environment where, as Carolyn Steel said, the supermarkets where Londoners buy more than 80% of their groceries refused to participate in consultations with the Mayor's London Food Strategy, it seems unlikely that sustainable food production and distribution will become the norm without legislative intervention. In her book, Steel quotes Cassiodorus, a Roman statesman who wrote: "You who control the transportation of food supplies are in charge, so to speak, of the city's lifeline, of its very throat." At the moment, Steel tells us, roughly 30 agrifood conglomerates—unelected, and with no responsibility other than to their shareholders—have almost unfettered control over London's food supply. Until that changes, urban agriculture can't help but remain "at the artwork stage"—an inspiring, attractive, and completely optional extra. [Previous guest posts by Nicola Twilley include Watershed Down, The Water Menu, Atmospheric Intoxication, Park Stories, and Zones of Exclusion].

[Image: The original fire house from Ghostbusters, seen here via Google Street View]. [Image: The original fire house from Ghostbusters, seen here via Google Street View].Every once in a while it's rumored that there will be a Ghostsbusters III – the current rumor being that Judd Apatow might produce – and so, today, while walking around the National Gallery of Modern Art here in Rome, in a state of 100º exhaustion, I got to thinking about what would make an interesting plot if BLDGBLOG were somehow hired to write the screenplay. And this is what I came up with: It's 1997. NYNEX is on the verge of being purchased by Bell Atlantic, after which point it will be dissolved in all but name. But all hell starts breaking loose. Pay phones ring for no reason, and they don't stop. Dead relatives call their families in the middle of the night. People, horrifically, even call themselves – but it's the person they used to be, phoning out of the blue, warning them about future misdirection. Every once in a while, though, something genuinely bad happens: someone answers the phone... and they go a little crazy. Thing is – spoiler alert – halfway through the film, the Ghostbusters realize that NYNEX isn't a phone system at all: it's the embedded nervous system of an angel – a fallen angel – and all those phone calls and dial-up modems in college dorm rooms and public pay phones are actually connected into the fiber-optic anatomy of a vast, ethereal organism that preceded the architectural build-up of Manhattan. Manhattan came afterwards, that is: NYNEX was here first. It's worth recalling, in fact, that NYNEX – at least according to Wikipedia – actually stood for New York/New England, "with the X representing the unknown future (or 'the uneXpected')." It's like Malcolm X's telephonically inclined, wiry cousin. So the phone system of Manhattan – all those voices! all those connections! leading one life to another – starts to act up, provoked by its dissolution into Bell Atlantic... and the Ghostbusters are called in to fix it. Fixing it involves rapid drives from telephone substation to telephone substation, from library to library, all while Dan Ackroyd's character keeps receiving phone calls about a family crisis... his ex-wife is calling... his dad is calling... they're urging him to stop this whole, crazy Ghostbusters business... He starts acting funny. The voices on the phone say strange things. They call at strange hours. He feels kinship with public pay phones; they sometimes ring as he walks past. He tries to call his family back – but they're not answering. Harold Ramis starts to suspect something. In the background there are shadowy figures called out to fix transmission lines – but they are actually wiring something up... something big... The whole movie then leads up to the granddaddy of them all: an electromagnetic confrontation inside the windowless, Brutalist telephone switching tower at 33 Thomas Street (rumored haunt of the ghost of Aleister Crowley).  [Image: 33 Thomas Street, via Wikipedia, "is a telephone exchange or wire center building which contains three major 4ESS switches used for interexchange (long distance) telephony..."]. [Image: 33 Thomas Street, via Wikipedia, "is a telephone exchange or wire center building which contains three major 4ESS switches used for interexchange (long distance) telephony..."].The opening scene: a pay phone on a sun-splashed street near Washington Square Park. You can see the famous arch in the background. A man is sitting nearby, outside a deli. He's got a bagel and a coffee and he's reading the New York Times. The phone starts to ring. He looks at it. It rings and rings. He gets up, finally, and approaches the phone – and he answers it. It's his dad. But he thought his dad was dead. Ghostbusters III. The city's telecommunications system is not some mere collection of copper wires and fiber optics, the film will suggest; it's actually the subtle anatomy of a barely understood supernatural being, an angel of rare metals embedded in the streets of Manhattan. Somewhere between AT&T and H.P. Lovecraft, by way of electromagnetized Egyptian mythology. These metals, Harold Ramis will explain, pushing up his eyeglasses, also correspond to materials used in pre-Christian burial rituals throughout Mesopotamia. Copper coffins. Traces of selenium found in embalming tools. He refers to Tiamat, dragon of multiple heads, and he draws mind-bending parallels between Middle Eastern mythology and the origins of NYNEX. NYNEX/ Tiamat. NYNEX/ Michael. NYNEX/ Metatron. Certain members of the audience think the whole thing sounds like bullshit. But they like the special effects. And who cares, anyway. So the movie will involve everyone from Guglielmo Marconi to Thomas Edison to Alexander Graham Bell (he's the "ultimate sorcerer," Dan Ackroyd exclaims, laughing along with the rest of us), and it will make reference to the hundreds of architecturally interesting telephone substations scattered throughout the greater New York region. It's voodoo meets urban infrastructure by way of Avital Ronell. Architecture students will flock to see it. Having seen the film, people will long for the days of pay telephones – when, according to the film's mythology, you were actually using the body of an angel to make local phone calls. Within the film, then, there are also brief scenes of excavation – a kind of angelic archaeology wherein Bill Murray digs through the plaster of tenement walls in search of ancient trunk lines. But he accidentally breaks into the plumbing. At one point, he and Ernie Hudson drive north along the Hudson, discussing Christian archangels, afraid to use the car phone, looking for some kind of old anchorage point for the phone system. They think maybe they can just shut the whole thing off. They are surrounded by dark trees and the scenography is breath-taking. Harold Ramis then uncovers a diagram of city streets and the exact locations of NYNEX lines; these line up with other diagrams from some Central European grimoire that he finds down in the basement of the New York Public Library. They're getting close, in other words. And that's when they discover 33 Thomas Street. In any case, the film is released in the summer of 2012 and it's a runaway blockbuster. It's "a return to American mythmaking," A.O. Scott writes in the New York Times, and there's immediate talk of a Ghostbusters IV. Manhattan is the wired center of a vast, global haunting, a transmission point crisscrossed by whispers above a magical infrastructure no one fully understands. Ghostbusters III: hire me, and I'll write it! I don't think it'd be a bad movie, actually.

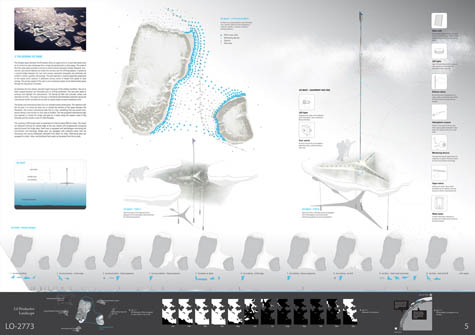

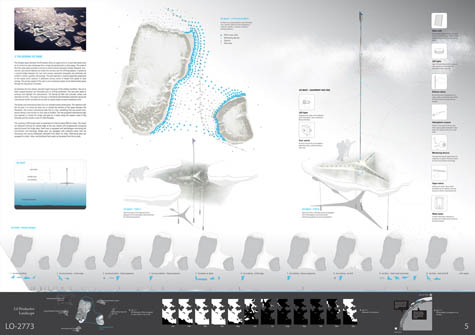

[Image: From "IceLink: Occupying the Temporal Seam" by Lateral Office]. [Image: From "IceLink: Occupying the Temporal Seam" by Lateral Office].In their submission to the recent competition to design a bridge across the Bering Strait – the Bering Strait Connection – Toronto's Lateral Office proposed "IceLink: Occupying the Temporal Seam." Lateral Office, of course, are also the brains behind the excellent blog InfraNet Lab, as well as the designers of both the Air Unit and the awesome Runways to Greenways plan proposed for Iceland – and IceLink is no less interesting than either of those.  [Image: From IceLink by Lateral Office]. [Image: From IceLink by Lateral Office].First, for those of you who did not see the original call for projects, the Bering Strait Connection described itself as a "project attempting to connect two continents": In a wide sense, it includes building a tunnel or a bridge at both ends of the strait, extending [the] existing railways of the United States and Russia, and laying a world highway around the coasts of the world, which requires a massive amount of construction. Architects were asked to design "a peace park with a bridging structure using the two islands, Big Diomede and Little Diomede at the Bering Strait," and a "proposal of how to connect two continents."  [Image: From IceLink by Lateral Office]. [Image: From IceLink by Lateral Office].In response to this, then, Lateral proposed: "1) a tunnel/bridge hybrid that runs along the international date line and accumulates diplomatic programs, and 2) a seasonal ice park that harvests ice floes into a global water vault." A global water vault: it's ideas like this that make me love architecture.  [Image: From IceLink by Lateral Office]. [Image: From IceLink by Lateral Office].So the site, of course, would straddle two very different timezones: that is, both today and tomorrow (or today and yesterday). If I wasn't living in a temporary apartment right now, and thus without access to my books, I would quote from Umberto Eco's intellectually pessimistic novel The Island of the Day Before. There, we read how a shipwrecked scientist repeatedly fails to come to grips with the temporal (and epistemological) fact of his maritime abandonment along the international date line. But, perhaps to the benefit of my readers, I can't. Instead, let me also mention The Cryptographer, a novel by Tobias Hill. While it would be hard actually to recommend the book, it's nonetheless worth mentioning Hill's use of the international date line as an origin point for a currency-destroying computer virus: the Date Line Virus. Hill's Date Line Virus spreads westward with the ticking of the clock – or the turning of the earth – erasing digital savings and scrambling all systems of measured economic value. That is, the world's entirely computer-based monetary system, hour by hour, goes mad. Clearly, then, from even only these two examples, the narrative possibilities – and intellectual stakes – of the international date line are fairly interesting to draw on. Or, for instance, check out this factoid, from that well-known source of scientific accuracy, Wikipedia: For two hours every day, at UTC 10:00–11:59, there are actually three different days observed at the same time. At UTC time Thursday 10:15, for example, it is Wednesday 23:15 in Samoa, which is eleven hours behind UTC, and it is Friday 00:15 in Kiritimati (separated from Samoa by the IDL), which is fourteen hours ahead of UTC. For the first hour (UTC 10:00–10:59), this phenomenon affects inhabited territories, whereas during the second hour (UTC 11:00–11:59) it only affects an uninhabited maritime time zone twelve hours behind UTC. For two hours, in other words, there are three different days happening on the earth simultaneously. But what about the spatial possibilities of the international date line? How can this strange temporal fissure in the planet's political and cultural landscape be taken advantage of architecturally?  [Image: From IceLink by Lateral Office]. [Image: From IceLink by Lateral Office].IceLink, its designers write, without much surprise, "seeks to capitalize and highlight [the Strait's] unique geography, climate, and context." However, they add, "The intent here is less to impose a new landscape in this context than to emphasize the sublime conditions already existing. Currently, the Bering Strait is a seasonal barometer of the impacts of climate change. The intent with this scheme is to offer spaces with which to reflect on the correlation between natural environments and their occupation." This is where we come to the project's "two primary infrastructural elements: a tunnel-bridge link and an ice park."  [Image: From IceLink by Lateral Office]. [Image: From IceLink by Lateral Office].The so-called "Bering Link" half of the project would consist of "bundled infrastructures," the architects explain; these infrastructures would span a distance of 85km, from Dezhnev, Russia, to Wales, Alaska. In the process, the Bering Link would skirt the Diomede islands, and even travel north-south atop the date line for 4km. Alongside this would be a series of new buildings, "concurrent with the international date line." Public and cultural programs intermittently rise above the bridge while research and education programs hang below the rail/road. Significant programs include a new United Nations headquarters, World Water Council headquarters, an Arctic Museum, and extensive oceanographic and meteorological facilities. It's a little hard to believe that the United Nations would move its headquarters to the middle of the Bering Strait – after all, thriller-reading Christians know that they'll soon be moving it to Baghdad – but it's a pretty ingenious move to put the World Water Council headquarters out there. Why? Here we come to the second half of Lateral's project: the "Bering Ice Park," a kind of floating archive and index of global climate change: Sea ice is often trapped between the Diomedes prior to drifting northward. The new park seeks to enhance and highlight this phenomenon. The Bering Ice Park will cultivate, collect and distribute ice floes. The extent of the park is defined by the Diomedes coastlines facing the international border and date line as well as natural ocean currents movement north. I'm reminded of BLDGBLOG's earlier look this month at the terroir of drinking water, in a guest post by Nicola Twilley: might specially cultivated Date Line Water™ from Lateral's Bering Ice Park someday arrive on the tables of high-end restaurants the world over? As it happens: no. The project described here did not manage to find a place amongst the finalists of the design competition. To see what did make the cut, take a look at the results over at Bustler.

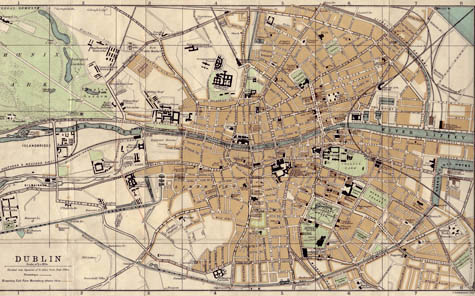

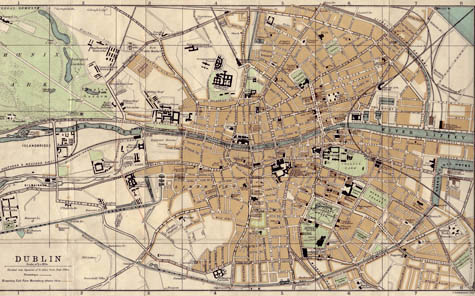

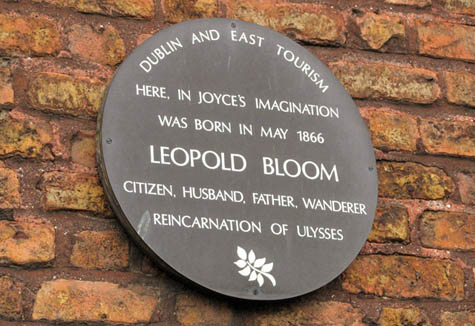

Yesterday, as James Joyce fans will know, was Bloomsday: June 16th. The day Leopold Bloom made his famous walk around Dublin in Joyce's 1922 novel Ulysses.  [Image: Street map of Dublin].Ulysses [Image: Street map of Dublin].Ulysses – considered something of the ultimate in literary modernism, as much for its mythical remaking of everyday life as for its often impenetrable abstraction, presaging Joyce's later linguistic kaleidoscope, Finnegan's Wake – was, for me, utterly transformed when my brother suggested that it was actually an attempt at descriptive realism. That is, should you want to describe a man's walk around the city in as detailed and realistic a way as possible, capturing every minor event and instant, then you would have to include the circumstances of that walk in their often bewildering totality: every fragmentary thought process, directionless flight of fancy, and irrelevant detail noticed along the way, via a million and one dead-ends. Things remembered and then forgotten. Deja vu. That daydream you had early today? That was, Ulysses suggests, part of the infrastructure of the city you live in. The city here becomes a kind of experiential labyrinth: it is something you walk through, certainly, but it is also something that rears up mythically to consume the thoughts of everyone residing within it. To say that Ulysses, then, is one of the most realistic urban novels ever written surely sounds like a joke to anyone not connected to academia – yet, once the apparent absurdity of such a statement wears off, it seems utterly ingenious. After all, how do you map the city down to its every last conceivable detail? And what if cartography is not the most appropriate tool to use? What if narrative – endlessly diverting narrative, latching onto distractions in every passing window and side-street, with no possible conversation or observation omitted – is the best way to diagram the urban world? In such a constellated wealth of minor points, "realism" becomes a useless haze – like listening to every conversation at a party simultaneously. And that's before you add internal monologues and descriptive details from the pubs and sidewalks all around you. In any case, there are many secondary points to make here. For instance, I'd actually suggest that the narrative position just outlined actually describes not a person at all but a surveillance camera – that is, the Ulysses of the 21st century would actually be produced via CCTV: it would be Total Information Awareness in narrative form.  But the whole point of this post was actually to ask two things: 1) What if Ulysses had been written before the construction of Dublin? That is, what if Dublin did not, in fact, precede and inspire Joyce's novel, but the city had, itself, actually been derived from Joyce's book? At the very least, this would be an awesome proposition for a design studio: read Ulysses and then design the city it describes... The differing responses would be fascinating. Further, this raises the question of whether a city has ever been built, directly inspired by a work of fiction. Of course, you could stretch the term fiction a bit, and say that those fundamental fictions of a nation's founding myths might have inspired a city – or an historic preservation district – or perhaps you could even say, as if channeling Michael Sorkin, that the city's zoning code is itself a monumental act of narrative modernism. But what about an actual novel? If you can take, say, Moonraker by Ian Fleming and turn it into a film – that is, Moonraker, directed by Lewis Gilbert – then could you also take a novel – here, Ulysses – and turn it into a city? 2) If you fed Ulysses into a milling machine – that is, if you input not a CAD file but a massive Microsoft Word document containing the complete text of Ulysses – what might be the spatial result? Would the streets and pubs and bedrooms and stairwells of Dublin be milled from a single block of wood? What if you fed Ulysses through a 3D printer? Oddly, I'm reminded here of something that has long fascinated me: quipu, the so-called knot language of the Inca. Quipu, to make a very long story short, is a way of braiding strands of animal hair or colored yarn together, using specific types of knot; these knots, arrayed in specific orders, thus communicate things to others – whether that's accounting information or perhaps even cultural myths. It was a form of writing, in other words, although its words were 3D shapes. As a brief aside, the possible paranoias of a quipu translator have always seemed particularly stunning to me: for instance, someone over-immersed in the world of Andean knot-languages becomes convinced that, in the drooping symmetry of a basketball net or in the shoelaces of strangers walking past on the street, there might be written messages: epic poems, secret codes, unintended diary entries. Instead of Freudian dream-analysis, you perform quipu knot-analysis, even examining the micro-fibers of strangers' clothing for hidden meanings... (It's worth mentioning that this exact idea actually appears in the unwatchably annoying film Wanted). In any case, I mention quipu here because I can't even believe how cool it would be if 3D printers might someday be used to create word-objects: little amorphous and abstract three-dimensional shapes that aren't just works of art, they are a new form of writing. Like quipu, they are 3D linguistics: words in space. The idea here that all those high-end design items you see lining the shelves of boutique shops in downtown Milan or Moscow or Manhattan are actually strange new, highly literal forms of communication, makes the mind reel. Spy films of the future! MI6's man in Havana goes into a specialty cookware shop where the salt and pepper shakers are not at all what they seem... Or, inspired by Alfred Hitchcock, the FBI begins leaving little figurines in empty hotel rooms, knowing that the next guest will be an undercover informer – and those abstract statuettes left behind in the cupboard actually encode the next location of rendezvous... And so on. So the point of this long tangent is this: if you fed Ulysses through a 3D printer, what might the resulting shapes be? What if the unexpected blobs and shapes could be considered a translation of the novel?  [Image: Historical maker for the birthplace of Leopold Bloom in Dublin]. [Image: Historical maker for the birthplace of Leopold Bloom in Dublin].Inspired by Bloomsday, then, it seems well-timed to ask not only how our cities can best be mapped – and if narrative is, in fact, the ideal cartographic strategy – but what other physical possibilities exist for narrative expression. Put another way: what if James Joyce had been raised in an era of cheap 3D printers? After all, given the possibilities outlined above, we might even someday be justified in concluding that Dublin itself is a written text, and that Ulysses is simply its most famous translation.

Perhaps proof that J.G. Ballard didn't really die, he simply took an engineering job at MIT, scientists at that venerable Massachusetts institution have designed a new concrete that will last 16,000 years. Called ultra-high-density concrete, or UHD, the material has so far proven rather strikingly resistant to deformation on the nano-scale – to what is commonly referred to as "creep." This has the (under other circumstances, quite alarming) effect that "a containment vessel for nuclear waste built to last 100 years with today's concrete could last up to 16,000 years if made with an ultra-high-density (UHD) concrete." (Emphasis added).So how long until we start building multistory car parks with this stuff? 16,000 years from now, architecture bloggers camped out for the summer in rented apartments in Houston – the new Rome – get to visit the still-standing remains of abandoned airfields, dead colosseums, and triumphal arches that once held highway flyovers? 16,000 years' worth of parking lots. 16,000 year's worth of building foundations. Perhaps this simply means that we're one step closer to mastering urban fossilization. (Thanks, Mike R.!)

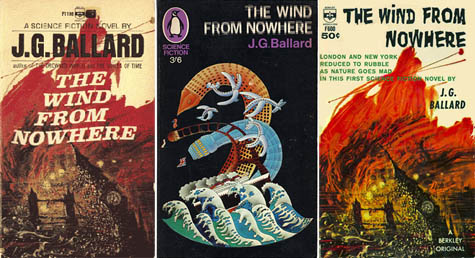

Like an inversion of J.G. Ballard's first novel, The Wind From Nowhere – in which winds blow to hurricane strength around the world, flattening cities, decimating civilization, and making readers wonder why the book wasn't simply written as a short story – it seems that winds across the continental U.S. are slowing down.  [Images: Three covers from J.G. Ballard's first novel, The Wind From Nowhere: "London and New York reduced to rubble," the cover on the right side reads, "as nature goes mad"]. [Images: Three covers from J.G. Ballard's first novel, The Wind From Nowhere: "London and New York reduced to rubble," the cover on the right side reads, "as nature goes mad"].As The New York Times reports, "wind speeds in the United States have dropped 15 to 30 percent over the course of about 30 years." There is absolutely no reason to assume that this trend will continue at the same pace – but, should it, the winds of America would come to a stand-still within just four or five generations. One of the suspected reasons behind this atmospheric deceleration is climate change, the NYT explains: As polar regions warm faster than the Equator... the temperature difference between them – and the pressure differential – shrinks. And, lower pressure differences mean slower winds. Of course, it shouldn't be surprising, meanwhile, that, "in scattered pockets of the country, wind speeds have risen." These sorts of changes are rarely homogenous: a cooling trend in one spot is matched by a warming trend in another; the death of breezes in one location is counteracted by increased number of hurricanes elsewhere. Nonetheless, how interesting to speculate what might happen if the atmosphere gradually did fail, falling still, forming the aerial equivalent of a glacier: hazy and unmoving, polluted and heavy, a kind of anti-hurricane with no less deadly effects in the long term. Certain plants would no longer pollinate. International travel, by both sea and air, would become unpredictable. The use of fossil fuels would skyrocket. I do wonder, then, if Ballard, given another few years in which to write, might have tried out this kind of anti-storm scenario, describing a world without aerial movement. The death of the sky.

Adventures in home foreclosure continue: empty homes in the U.S. hurricane belt run the risk of becoming "wind-propelled debris." As the Associated Press reports, "communities at the epicenter of the nation's housing crisis are coming to realize that this year's hurricane season, which began this month, represents yet another pitfall." In other words, "hurricanes could make hazards of thousands of foreclosed-upon houses" – turning those homes into airborne projectiles. Building-storms. After all, the AP asks, "who will secure all the foreclosed homes if a storm does approach?" It must be an eery feeling, I'd suspect, when you realize that all those empty houses sitting around you might someday be weaponized: latent storms of wood and vinyl siding just waiting for the moment when they can pick up and whirl through the streets, like something out of Transformers 3. But do you tear the houses down in advance of a storm that might never arrive? Or do you surround your own home with vast nets and deflection shields for protection against inevitable debris? Ironically, as Steve Silberman – who first sent me this link – points out, there is simultaneous interest in using these very foreclosed homes as hurricane shelters. As the Florida Courier points out, this idea, if implemented, would also "address a source of concern among emergency specialists in Florida: the growing number of vacant homes that could be splintered into construction debris by a hurricane if no one secures them with shutters and plywood."

|

|

[Image: From OnSite.12, Bed Supperclub, Bangkok (2009) by Sebastien Wierinck].

[Image: From OnSite.12, Bed Supperclub, Bangkok (2009) by Sebastien Wierinck]. [Image: From OnSite.12, Bed Supperclub, Bangkok (2009) by Sebastien Wierinck].

[Image: From OnSite.12, Bed Supperclub, Bangkok (2009) by Sebastien Wierinck]. [Image: From OnSite.14, Transmediale, Berlin (2009), by Sebastien Wierinck].

[Image: From OnSite.14, Transmediale, Berlin (2009), by Sebastien Wierinck]. [Image: From OnSite.14, Transmediale, Berlin (2009), by Sebastien Wierinck].

[Image: From OnSite.14, Transmediale, Berlin (2009), by Sebastien Wierinck].

[Image: All systems go... Original photo by Jim Grossman, courtesy of

[Image: All systems go... Original photo by Jim Grossman, courtesy of  [Image: Photo of the Atlantic Avenue train tunnel taken by

[Image: Photo of the Atlantic Avenue train tunnel taken by  [Image: Lightning storm over Boston, ca. 1967; photo courtesy of

[Image: Lightning storm over Boston, ca. 1967; photo courtesy of  [Image: A portrait of the

[Image: A portrait of the  [Image: The Chrysler Building – a sponsored building – montaged by Flickr-user

[Image: The Chrysler Building – a sponsored building – montaged by Flickr-user  [Images: Geothermal projects and earthquake clusters in northern California; graphics by Hannah Fairfield, Xaquín G.V., James Glanz, and Erin Aigner for

[Images: Geothermal projects and earthquake clusters in northern California; graphics by Hannah Fairfield, Xaquín G.V., James Glanz, and Erin Aigner for  [Image: Artificial terrain rises from below... A screenshot from

[Image: Artificial terrain rises from below... A screenshot from  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: It's

[Image: It's  [Image: A scene from Alfred Hitchcock's film

[Image: A scene from Alfred Hitchcock's film  [Image: Trees in the museum each have their own sidewalk marker, which gives their name and extension number].

[Image: Trees in the museum each have their own sidewalk marker, which gives their name and extension number]. [Image: A section of the

[Image: A section of the  [Image: A computer-generated image of Klaus Lackner's prototype "synthetic tree," which would remove carbon dioxide directly from the air; image courtesy of Columbia University].

[Image: A computer-generated image of Klaus Lackner's prototype "synthetic tree," which would remove carbon dioxide directly from the air; image courtesy of Columbia University]. [Image: Eric Sanderson pointing at a map of the Bronx; photo by Katie Holten].

[Image: Eric Sanderson pointing at a map of the Bronx; photo by Katie Holten]. [Image: The Bronx

[Image: The Bronx  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: Ebenezer Howard's original scheme for the

[Image: Ebenezer Howard's original scheme for the  [Image: A lemon grown in Dulwich; photograph by Jonathan Gales (2008), ©

[Image: A lemon grown in Dulwich; photograph by Jonathan Gales (2008), © [Image: From Mikey Tomkins's series of

[Image: From Mikey Tomkins's series of  [Image: The original fire house from

[Image: The original fire house from  [Image: 33 Thomas Street, via

[Image: 33 Thomas Street, via  [Image: From "IceLink: Occupying the Temporal Seam" by

[Image: From "IceLink: Occupying the Temporal Seam" by  [Image: From IceLink by

[Image: From IceLink by  [Image: From IceLink by

[Image: From IceLink by  [Image: From IceLink by

[Image: From IceLink by  [Image: From IceLink by

[Image: From IceLink by  [Image: From IceLink by

[Image: From IceLink by  [Image: Street map of

[Image: Street map of  But the whole point of this post was actually to ask two things:

But the whole point of this post was actually to ask two things: [Image: Historical maker for the birthplace of Leopold Bloom in

[Image: Historical maker for the birthplace of Leopold Bloom in  [Images: Three covers from J.G. Ballard's first novel,

[Images: Three covers from J.G. Ballard's first novel,