|

|

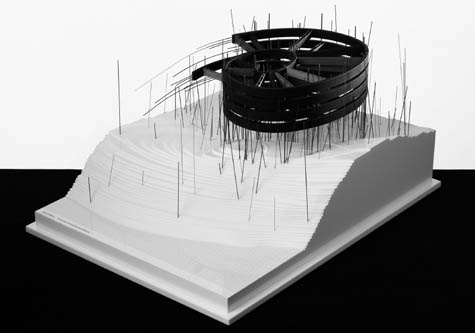

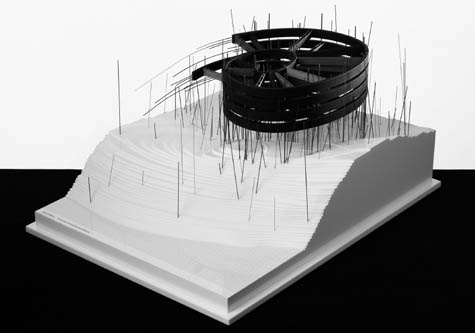

One of many projects collected in the first issue of P.E.A.R., released last month, is the Bat Spiral by London designers friend and company.  [Image: The Bat Spiral by friend and company]. [Image: The Bat Spiral by friend and company].Serving as further evidence that architecture is not solely built for humans – after all, other species build architecture, respond to architecture, and colonize architecture quite readily – the Bat Spiral offers an elevated habitat for seventeen species of British bat. From the architects: Twenty-four different types of timber roosts are positioned within the concrete spiral as if they were the spokes of a wheel. Each roost position is determined by the orientation of the sun, shade and prevailing winds. The roosts are painted black externally to maximize heat gain from the sun... Inside, amidst gaps, reclaimed wood beams, and concrete spans poured in-situ, are "four levels of habitation," including feeding perches and access holes. Optional "mating roosts" can also be added as demand requires. Prefab modular animal housing. More images of the project are available in P.E.A.R.. I'm led to wonder, however, what non-human future might await something like Aranda\Lasch's 10 Mile Spiral if it were to be constructed – and later abandoned – amidst an ecosystem for bats... Perhaps we are inadvertently building the future infrastructure of an animal world.

[Image: "The ghost cinema" by Phill Davison, used through Creative Commons]. [Image: "The ghost cinema" by Phill Davison, used through Creative Commons].An article posted today on New Scientist suggests that, over the course of a 150-minute film, audience members will miss an incredible fifteen minutes simply through the act of blinking – but also that people watching a film tend to blink at the same time. It's called "synchronized blinking," and it means that "we subconsciously control the timing of blinks to make sure we don't miss anything important" – with the addendum that, "because we tend to watch films in a similar way, moviegoers often blink in unison." That is, they blink during "non-critical" moments of plot or action, creating a kind of perceptual cutting-room floor. On the one hand, then, I'm curious if this means that clever editors, like something out of Fight Club, might be able to insert strange things into those predicted moments of cinematic calm – moments deemed safe for blinking – simply to see if anyone notices, but I'm also left wondering if there is an architectural equivalent to this: a spatial moment inside a building in which it seems safest for us to blink. In other words, do people not blink when they first walk into a space like Rome's Pantheon or into Grand Central Station – or is that exactly when they do blink, as if visually marking for themselves a transition from exterior to interior? It would seem, then, that if film has moments of synchronized blinking, then so might architecture – but when do we choose to blink when experiencing architectural space, and do those moments tend to occur for all of us at the same time? How could we test this?  [Image: The Pantheon, photographed by Nicola Twilley]. [Image: The Pantheon, photographed by Nicola Twilley].Further, if there is, in fact, a moment inside a building somewhere where almost literally everyone blinks– say, in the lobby of the Museum of Modern Art, or in a bathroom corridor in the history building at your own university – could we say that that space is somehow yet to be fully seen? It is the spatial equivalent of those fifteen minutes of a film that no one realized they missed. After all, perhaps there's a detail in your own house that you've never actually seen before – and it's because you tend to blink as you walk past it. Your own body assumes, outside conscious awareness, that this must be a safe space for blinking; it's near a window, or the colors are very dull. Perhaps that's how spiderwebs build up: you literally don't see them. On a much larger scale, meanwhile, are there stretches of highway somewhere outside town where the scenery gets a bit boring – and so everyone starts to blink, more or less at the same time, thus visually removing from collective cultural awareness that McDonald's, or that abandoned house, tucked away over there beside the trees? And could you locate that exact moment of blindness – could you find blinkspots throughout the urban fabric – and start to build things there? Architecture becomes a three-dimensional test landscape for the neurology of blinking.  [Image: A human blink, via Wikipedia]. [Image: A human blink, via Wikipedia].For instance, if people driving 65 mph travel, say, five feet with every blink, then what spatial and architectural possibilities exist within that five feet? What are the spatial possibilities of the blink? I'm reminded of certain zoning laws in which you need to consider the exact amount of shadow your building will cast on the neighborhood around it before beginning construction. But what about zoning for blinks? Can you zone a building for maximum blinks? Or perhaps the opposite: a new genre of architecture, specially designed for Halloween fun houses, in which it's too stressful to close your eyes even for a micro-second... (Spotted via @jimrossignol).

Urban Islands continues apace down here in Sydney, with Day Five beginning in about an hour. While I'll describe the actual studio process in some detail later on, it seems worth recounting our trip out to Cockatoo Island – a derelict shipbuilding site and former prison in the Sydney Harbor – earlier this week.

[Image: The dimensions of an island: a sign posted on Cockatoo]. [Image: The dimensions of an island: a sign posted on Cockatoo].

We went out as a massive group of about 70 people and spent a bit more than five hours there, wandering around through old turbine halls and tunnels, walking past fenced-off but still functioning lift shafts cut directly through an eroded plateau of sandstone, and exploring former convict barracks, exercise yards, a Submarine Weapons Workshop, and the lost interiors of buildings demolished long ago, their internal walls, spaces, and bays still marked by iron rails set rhythmically in the concrete.

The first step was for our students to install small models that they'd built the night before, fitting them into cubbyholes inside an old warehouse near the turbine hall.

The cubbyholes themselves were all very strangely labeled, however, referring to old tools and other handheld pieces of industrial equipment; but the words written on them in black lettering were more like a set-list by the Aphex Twin than a serious description of useful implements: Vodex Elect, Murex Vodex, Yorkshire Flux.

After that first exercise was over – and there were some fantastic projects on display, from a conic room-amplification device to mirrored boxes and temperature-sensitive geometries – we broke up into our respective tutorial groups, approximately 16 students per group, and headed outside to sit amidst that old iron grid in the concrete, looking out through a missing interior that still seemed to haunt the island's perimeter.

[Image: The gridded rails of a lost interior, Cockatoo Island, in Sydney Harbor]. [Image: The gridded rails of a lost interior, Cockatoo Island, in Sydney Harbor].

I'll explain in another post what it is that I'm having my students do – though I will say that it involves what I hope is an exciting mix of formal landscape analysis, combinatorial mythology, and Tarot cards (yes, Tarot cards) – but this first day out on the site was more of an introduction to the spectacular historical landscapes on display there in the harbor.

From recently discovered "convict structures" under active excavation at the top of a hill to the long stories of ships constructed on Cockatoo – warships drifting outward in an endless archipelago of micro-islands – by way of the extraordinary Mould Loft, where massive ribs and geometries for future ships were outlined with chalk drawings on the floor, cut into wood, sent down piece by piece to be remade in metal, and then assembled again, like dinosaur skeletons, into boats and submarines, Cockatoo is a three-dimensional catalog of unique situations and spaces.

When does a ship cease to be a part of the island that created it? Perhaps ships are to Cockatoo as pollen is to flowers.

There is electrical equipment still sitting there like something from The Prestige, converting DC current from mainland Australia to the island's AC needs; there is a locked switchboard room inside of which phonecalls used to be connected through grids of wires; and there are entire missing hillsides – artificial cliffs still marked with drilled incisions for dynamite – that you then realize aren't missing at all, they've simply been transformed into the ground you're standing on, the island having been expanded in size nearly fourfold through a coastal growth that pushed the island's perimeter further and further out to the sea, like terrestrial rings for a maritime Saturn.

There are moving walls formerly used to plug-up the dry docks; there is ship-launching equipment; there was the deliberate feeding of harbor sharks to turn them into a living security fence against the island's 19th-century prisoners; and there is the incredible angular cross-bedding of ancient sand dunes now frozen into permanent form as the island's central plateau.

There is a filled well; a campground for tourists; inflatable "slave docks" that could temporarily expand the outer edge of the island; and all around us were things that had yet to be constructed, from viewing platforms planned by the Harbour Trust to our own students' future installations.

[Image: Cockatoo Island in profile]. [Image: Cockatoo Island in profile].

While I suppose all islands lend themselves well to mythology, Cockatoo seems particularly well-suited to a kind of over-the-top symbolic analysis – the bizarrely preserved film set from Wolverine, the space of the Turbine Hall so immeasurably huge that they had to install visual guide tags for laser-based surveying equipment, the escaped ship that beached itself on a neighboring island – that it seems impossible to believe architects working there could not foreground the narrative potential of the site. Even if only as a way to recombine and situationally understand the possibilities of an island, delving into the mythology of Cockatoo seems both incredibly fun and architecturally necessary.

It's an history full of plane crashes and visiting aviators, with a backwards warship that arrived without a bow to be temporarily repaired by workers on inflatable slave docks, and there are the hollow voids of old grain silos visible in section on the sides of collapsed hills, connected onward to an internal network of rock-cut drains and reservoirs...

Obviously, I hope my own studio here – breaking down Cockatoo into its major and minor spatial types and material details for the purpose of performing an oblique combinatorial analysis – will draw on these histories and forms, but we'll have to see if two weeks is enough time even to begin exploring such extraordinary symbolic potential.

(For a bit more about Urban Islands, check out Design + Build and these two posts by Nick Sowers of Soundscrapers fame).

[Image: Sydney's Cockatoo Island, site of Urban Islands]. [Image: Sydney's Cockatoo Island, site of Urban Islands].As I mentioned several months ago, I'm in Sydney, Australia, for the next two weeks to teach a design studio here called Urban Islands. It's a studio inspired by the amazing Cockatoo Island, an abandoned industrial site – former prison, former shipyard, former quarry, present campground and concert venue, ongoing archaeological site, future megastructural weather-altering agri-utopian astronomy research station at sea (or whatever our students decide to make it) – in Sydney Harbor. The studio, in fact, starts in about three hours (as I have insane jetlag and have been up since 4am). My fellow instructors here are awesome – including Mark Smout of Smout Allen and Mette Ramsgard Thomsen – and it's all been put together by the wizards behind lean productions. I have to say that I am genuinely excited about my own studio – I've got some cool ideas in mind, and I hope to post not only the design brief itself but the resulting student work here on the blog – and I'm also looking forward to the wide variety of subsidiary events. One of those takes place tomorrow evening here in Sydney, at a place called the Tusculum, run by the Australian Institute of Architects. I'll be speaking about blogging, digital publishing, information, the city, public interfaces, etc. etc., with two legends of the blogosphere I've long admired: Dan Hill of City of Sound and Marcus Trimble of Super Colossal. It costs $10 for non-AIA members, it starts at 6:30pm, and it's at 3 Manning Street in Potts Point. Next Tuesday, 21 July, at the same time and place, Mark Smout and Mette Ramsgard Thomsen will be presenting – don't miss it.  [Image: This season's lecture schedule at Sydney's Tusculum; view larger]. [Image: This season's lecture schedule at Sydney's Tusculum; view larger].If you'll excuse the rambling nature of this post, meanwhile, my wife and I are actually staying in Potts Point, and we're located basically right across the street from a Saturday morning farmers' market where we got into a conversation early on our first morning here with a man selling gourmet mushrooms that were grown, he said, inside repurposed railroad tunnels south of the city in Mittagong. I would love to visit those tunnels! Cockatoo Island, in fact, is actually honeycombed with old tunnels dug directly out of the site's bedrock – so perhaps some strange form of subterranean myco-agriculture might pop up in a few student designs over the next two weeks. Mushroom farming in the underworld. Or perhaps even the high-tech cultivation of pharmaceutical biocompounds by UV light in what used to be a submarine-repair facility (the island also houses a former submarine-repair facility!)... In any case, I hate to sound like a broken record but this could very well mean that I will be short on posts for the next bit – and July could thus continue to be a pretty slow month (although thanks to all the new readers coming in from various reviews of The BLDGBLOG Book! good to see you here). So if you stop by the site ten days from now and it looks more or less the same – now you know why. However, I can always be found on Twitter: @bldgblog. And if you want to keep up on the action at Urban Islands, Twitter's your friend: @urbanislands. Otherwise, more soon!

For his or her latest project, a well-known (but not necessarily well-liked) artist convinces a number of architects – from dRMM, ECDM, and Vaillo + Irigaray, to SOM, mos, Beckmann N'Thepe, and INABA – to include in some future building a small room that the artist herself has designed. It's the exact same room, and it will be repeated again and again, throughout numerous structures around the world – but it will be done without any public acknowledgement that the rooms exist. It's an art project no on knows about. These rooms' presence inside the buildings will thus be kept a secret; no one will know that they exist, let alone where they all might be. A hotel in Barcelona, a library in Wales, a private home somewhere in Midi-Pyrénées, a pharmaceutical HQ outside Singapore: these and other projects all contain a room. Within a year, reports surface on various travel blogs about intense spells of déjà vu experienced by visitors to one or more of these buildings. Gradually, urban myths even appear – and soon Nick Paumgarten of The New Yorker reports on the rise of something called the "room-detection industry," researching whether or not certain buildings contain identical internal spaces. It's all very strange and a discussion quite limited to the world of global frequent flyers; the art world, understandably, takes no notice of these rooms at all. But then the project is revealed a decade later, unexpectedly, in an exclusive interview with Artforum. All ten rooms have been installed, and their locations are made known, complete with an interactive map posted on artforum.com; one of the rooms, however, was demolished in 2011 when the building it was in was taken down ( ...or was it?, PhD students ask, writing term papers at Princeton). Many people are amazed by this story; most people don't really care, considering it pure wankery. Some, however, are thrilled beyond imagining, having themselves long suspected that they might have encountered this very project – a room at the Tokyo airport, or deep inside an outer London convention center – but they had simply filed it away as faulty memories. But it was real: they really did experience the same environment twice, with no explanation, inside two radically different buildings on opposite sides of the planet. However, reports of further rooms begin circulating, literally as early as the comments thread on the interview. People simply do not believe that the project is over. There's an eleventh room, some say, in a Seattle hospital – and they've got photographs to prove it. There's a twelfth room in Morocco; a well-known journalist claims to have been there just last week. Then the knock-offs begin to appear: illegally pirated interiors designed to fool the wary. None of which would really have interested you, had you not yourself just opened the door of a temporary flat-sit in Sydney, where you'll be for the next two weeks, only to drop your bags to the floor in sheer wonderment. You've seen this room before..., you realize. It's the thirteenth room...

Launching just today is an awesome new ideas competition called Reburbia. In a future where limited natural resources will force us to find better solutions for density and efficiency, what will become of the cul-de-sacs, cookie-cutter tract houses and generic strip malls that have long upheld the diffuse infrastructure of suburbia? How can we redirect these existing spaces to promote sustainability, walkability, and community? How would you put the suburbs to better use? Would you replace them altogether? Or, from spaceports to agricultural plots, from newly walkable town cores to micronations, what should the suburbs become? Perhaps empty, foreclosed houses should be transformed into, say, zoos for the displaced native species of the region... Or perhaps every house on a certain cul-de-sac should be linked by paths and awnings and turned into a library: fiction in one house, history in another... Or perhaps the suburbs should simply become a ruins park, rotting in on themselves in summer thunderstorms.  Co-sponsored by Inhabitat, the contest's judges are Jill Fehrenbacher, Sarah Rich, Fritz Haeg, Paul Petrunia, Thomas Ermacora, Allan Chochinov, and myself. It's a fantastic group of people to be with, I have to say, and I can't wait to see how people respond. So go theoretical, go structural, go narrative, go botanical, go cynical, go scifi: tell us how you would redesign the suburbs. Check out the Reburbia website for more info, including the schedule. And good luck!

[Image: From Kevin Slavin's talk last night at the BLDGBLOG Book launch party; there is an interview with Slavin in the book – don't miss it! Photo by Matt Jones]. [Image: From Kevin Slavin's talk last night at the BLDGBLOG Book launch party; there is an interview with Slavin in the book – don't miss it! Photo by Matt Jones].I'll be on the road again for nearly two days, presumably without internet access, flying down to Sydney for Urban Islands. However, I had a blast last night at The BLDGBLOG Book launch party and so I wanted to say thanks to everyone who came out. Even with last night's Tube-flooding rain storms, we managed to pack the place out. Kevin Slavin, who appears in a previously unpublished interview in The BLDGBLOG Book, kicked off the whole thing with a fantastic introduction to his own work – covering urban games, homesickness, the digital uncanny, payphone hijacking, and even shark clamps. Matt Jones has already uploaded a few pictures of Kevin in action. I was also excited as hell finally to meet Siologen, of the sadly now-missing International Urban Glow, after being blown away by his photos for so many years – some of which appear in the book – as well as to meet Magnus Larsson of Dune fame, novelist Clare Dudman, P.D. Smith of Doomsday Men, designer Anab Jain, blogger Andrew Ray behind the excellent Some landscapes, and all the other people I got to see again. So thanks – it was a great night. It also seemed like a well-timed launch, as I'm still reeling from the fact that the book was chosen just this week by Amazon.com as one of their " Best Hidden Gems of 2009... So Far." In any case, huge thanks, as well, to the Architectural Association, Wired UK, and Liam Young for teaming up to make last night happen. Also, I forgot to mention the other day that July 5th was BLDGBLOG's 5th birthday – so happy birthday, little mo', and thanks for being there to host my writing. Regular posts will return soon...

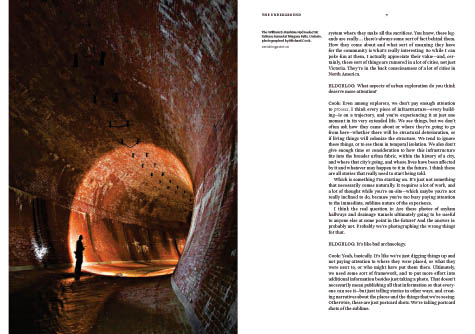

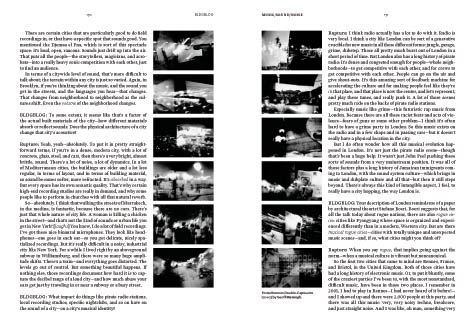

Considering the image that's been sitting up on top of the righthand column here for several months now, it might be hard to have missed the fact that there's a BLDGBLOG Book coming out. However, it also might not be entirely clear what the book is about, what's in it, or even who it's for; it might not be clear, in other words, why you should consider reading it.  [Image: An illustration by Brendan Callahan, from The BLDGBLOG Book]. [Image: An illustration by Brendan Callahan, from The BLDGBLOG Book].I thought, then, as the book is now shipping around the world and there's even an official launch party tomorrow night at the Architectural Association in London, that there's never been a better time to give everybody a quick tour through the book's major highlights. So here is a typically internet-ish list of ten reasons why you should read The BLDGBLOG Book. 1) The book itself! There are nearly 300 pages, close to 115,000 words, and approximately 275 images – and the whole thing is crammed full of sidebars, long captions, running text, and interstitial chapters scattered like blog posts in between. While you could sit down and read the whole thing through in two or three sittings, most likely it will become something you can turn to again and again – at the beach, in the studio, on an airplane flight – to look for ideas, visual inspiration, or even just a list of further things to read. Write notes in the margins. Google things you'd never heard of before. Reread a few sections. Option certain ideas for future blockbuster films... There's so much content in The BLDGBLOG Book that there's undoubtedly something for everyone: buildings, myths, gadgets, and paintings, short stories, maps, and comics, Mars photography, Gothic horror, and brand new interviews. It's got 19th-century ruins paintings, artificial glaciers, and countless speculative projects by some of today's most exciting architects – among a hundred thousand other things that will hopefully keep you coming back to the book for a long time to come.  [Images: Two original comic strips by Joe Alterio and BLDGBLOG for The BLDGBLOG Book].2) [Images: Two original comic strips by Joe Alterio and BLDGBLOG for The BLDGBLOG Book].2) For years now I've suggested that architectural ideas can be articulated, often extraordinarily well, in the form of graphic novels and comic books – so it seemed like I should finally try that theory out for myself. The book thus comes with two original comic strips, created in collaboration with San Francisco-based illustrator Joe Alterio: "Thames 1, 2, 3" and "Excavation National Park." They're featured on the inside covers, one of them without words, the other a much longer scenario in which most of London is underwater, transformed into "an archipelago of flood walls and island fortresses." There are Conradian references and tide-energy machines. Joe's artwork, I have to say, is stunning – it's precise and clean, yet tightly energetic – and, with any luck, he and I will be working together again in the future. (Joe also designed the logo for Postopolis! LA).  [Image: An illustration by Brendan Callahan, from The BLDGBLOG Book].3) [Image: An illustration by Brendan Callahan, from The BLDGBLOG Book].3) The book also has dozens of full-color, original illustrations by Brendan Callahan, a friend and former coworker. Brendan and I spent many a lunchtime break together back in San Francisco going over preliminary sketches and ideas for the book – and I think he hit the ball right out of the park here, coming back at the end, after sometimes excruciatingly vague art direction from yours truly (sorry, Brendan!), with detailed and very witty full-page images: architectural reefs, domesticated Northern Lights, endangered geological formations, underground cities, sound mirrors, overgrown freeways, hot air balloon concerts of subliminal nighttime music, buttressed buttresses, and even Miesian prescription drugs... For Brendan's illustrations alone, the book is well worth picking up. 4) The book is dotted with awesome interviews – from edited versions of BLDGBLOG's earlier discussions with classicist Mary Beard, urban explorer Michael Cook, theorist and historian Mike Davis, game designer Daniel Dociu, photographer David Maisel, novelist Patrick McGrath, photographer Simon Norfolk, and writer Jeff VanderMeer, to an expanded interview with architect Lebbeus Woods – discussing his project "Einstein Tomb," Arthur C. Clarke's novel Rendezvous with Rama, and much more. Beyond that, there are brand new, exclusive, and otherwise unpublished interviews with Archigram co-founder Sir Peter Cook, architect and writer Sam Jacob, musician DJ /rupture, urban games entrepreneur Kevin Slavin, and author Tom Vanderbilt. There are even short email interviews with fellow bloggers Bryan Finoki and Alexander Trevi, as well as with photographers Stanley Greenberg and Richard Mosse – lending the book so many other voices that, even if you don't like my own particular take on things, it should be easy enough to find a perspective here that appeals to you.    [Images: Spreads from The BLDGBLOG Book].5) [Images: Spreads from The BLDGBLOG Book].5) The book wouldn't be half as visually interesting as it I think it's turned out to be without the eye-popping photography of Edward Burtynsky, Michael Cook, Emiliano Granado, Stanley Greenberg, Ilkka Halso, David Maisel, Richard Mosse, Simon Norfolk, Bas Princen, Siologen, and many, many others (including NASA, the United States Navy, and the Army Corps of Engineers). All of even that, however, is in addition to architectural projects from Smout Allen, Agents of Change, Archigram, Aranda\Lasch, Minsuk Cho & Jeffery Inaba, FAT, Vicente Guallart, Lateral Office, Studio Lindfors, LOT-EK, Andrew Maynard, Haus-Rucker-Co., Joel Sanders, and Iwamoto Scott – and there are posters by Steve Lambert and Packard Jennings, video game environments by Daniel Dociu, "spam architecture" by Alex Dragulescu – and the list goes on and on.  [Image: A spread from The BLDGBLOG Book, designed by MacFadden & Thorpe].6) [Image: A spread from The BLDGBLOG Book, designed by MacFadden & Thorpe].6) The book is beautifully designed by MacFadden & Thorpe – with a clear and legible use of the page grid, great font choices (including Avenir, which you see in BLDGBLOG's logo), full-bleed images, and different-colored paper. It's a solid book: it looks and feels great, and it's durable. Designers Brett MacFadden and Scott Thorpe worked down to the tiniest level of detail to get it all lined up and functioning; Scott and I, in particular, often met after work last year at MacFadden & Thorpe's Mission studio to go over the book, page by page – a fantastic way to put together a project like this. One minor design detail that I like, for instance, becomes apparent after you shelve the book: the spine itself contains the table of contents. 7) It's probably not entirely surprising that I might have one or two good things to say about the book, having spent so much time working on it – but I'm not the only one. Here's a brief sample of what other people think of The BLDGBLOG Book... The back-cover blurbs come from Academy Award-winning director Errol Morris; Jeff Gordinier, Editor-at-Large of DETAILS magazine and author of X Saves the World; Justin McGuirk, Editor-in-Chief of Icon; Lawrence Weschler, National Book Critics Circle Award-winning author of, among many other things, Mr. Wilson's Cabinet Of Wonder; Joseph Grima, executive director of New York's legendary Storefront for Art and Architecture; and Sarah Rich, managing editor of the Worldchanging book. Meanwhile, just this past weekend, The Guardian wrote that the book has a "Wellsian ability to conjure up the structures and spaces of the future," and that it "fizzes with new ideas about the architecture that frames our lives." Literally tonight, then, as I sat down to read back through this post on a quest for lame phrases or typos, Amazon.com announced that The BLDGBLOG Book is one of their " Best Hidden Gems of 2009... So Far" – calling it a "gorgeous object" that will "build a new room in your brain." Wired enthusiastically recommends that you read it – as does Dwell – and SEED Magazine has called it one of their "Books to Read Now," adding that The BLDGBLOG Book's "freewheeling explorations of how we may come to interact with our buildings, our cities, and our planet draw from every branch of science (plus a few from science fiction)." Allison Arieff calls it " highly recommended reading." Obviously, not everyone in the world is going to like the book – and if you don't, of course, let me know what you think in the comments – but hopefully these are a good indication that the book has been put together well.  [Image: The beginning of the Further Reading list, from The BLDGBLOG Book].8) [Image: The beginning of the Further Reading list, from The BLDGBLOG Book].8) Toward the end of the book is an extensive "Further Reading" list, mostly referring to print media (I decided that a list of blogs and websites would rapidly become obsolete, as they come and go so quickly). However, this is a solid reading (and viewing) list, encompassing everything from Foucault's Pendulum to Ghostbusters, Bunker Archeology and William Burroughs to Giordano Bruno and Alfred Hitchcock, Piranesi to Papillon. The only down side, of course, is that I already have a half-dozen things I'd like to add – for instance, John Christopher's Death of Grass and Kaputt by Curzio Malaparte – but that's life. If you are at all curious about which books, films, and magazines (and even a few websites) are being consumed behind the scenes here at BLDGBLOG, there's no better place to start than The BLDGBLOG Book's long list of Further Reading. Photocopy it and give it to friends. Or read your way through it, checking off titles one by one.  [Image: The Autographs page, from The BLDGBLOG Book].9) [Image: The Autographs page, from The BLDGBLOG Book].9) Coming just after the Further Reading list there is... the Autographs page. This is where you can ensure your copy of The BLDGBLOG Book becomes totally unique to you, as each copy comes with pre-labelled spaces in which to collect certain autographs... by Lebbeus Woods, Walter Murch, Siologen, Steven Spielberg, Rachel Whiteread, and even Brad Pitt. Why not? Now Brad Pitt, for instance, is all but guaranteed to be confronted someday with a copy of The BLDGBLOG Book – and if you ever decide to get rid of the thing it will be worth $500 on eBay. Value-added! Unfortunately it's now impossible for anyone to get every name signed – with the death of novelist J.G. Ballard – but it would be genuinely interesting to see who can fill up the autographs fastest. Going to Denmark on holiday? Well, bring along The BLDGBLOG Book in case you run into Bjarke Ingels. Headed for Los Angeles? Better bring The BLDGBLOG Book – and stop by CLUI or SCI-Arc to get signatures from Matthew Coolidge and Mary-Ann Ray... 10) Finally, why should you read The BLDGBLOG Book? Again, because of the content. There are so many interesting things in there, from tectonic maps of the earth's evolving surface to previously unpublished documentation of a campaign to stabilize geological forms in Utah using spray-on adhesives manufactured by the automobile industry. There are acoustically sophisticated underground cities accidentally discovered by rural farmers and there are U.S. military plans for the weaponization of hurricanes. There is the flooded London of the 27th century and there is the deliberate demolition of architecture as an act of international war. Lost film sets, space seeds, and Stalinist sleep labs sit beside occupied cities and flying orchestras; fossil rivers flow by rogue adventure tourism firms, hydrological models, and the groaning sounds of climate-changed glaciers. There are buildings, speculative cities, and landscape futures.  [Image: A spread from The BLDGBLOG Book, featuring a photograph by Ilkka Halso]. [Image: A spread from The BLDGBLOG Book, featuring a photograph by Ilkka Halso].So check it out if you get a chance – I hugely appreciate any and all interest in the book. If you've bought a copy already, of course, I owe you a genuine thanks! And, again, if you're in London on Tuesday, 7 July, from 6-8pm, I'd love to see you at The BLDGBLOG Book's official launch party at the Architectural Association.

After the National Security Agency "maxed out the capacity of the Baltimore area power grid," according to an article in The Register – itself citing The Baltimore Sun – due to the near-endless electrical needs of its wire-tapping supercomputers, the NSA has begun planning the construction of a brand new, $2 billion data center in the deserts of Utah.  [Image: Photo by Thundered Cat]. [Image: Photo by Thundered Cat].There, a vast, million-square-foot warehouse might thus soon rise at the intersection of two major national "power corridors." The Agency, we read, hopes eventually "to decentralize its computing resources and tap regions with ample supplies of lower-cost electricity." While I've already written about the literary implications of server farms – that is, server farms as the library of the future – and I don't want to repeat that analysis here, I'm led to at least two further questions: 1) Is there a role for architects in the construction of rural data centers for the U.S. intelligence services, and what might Vitruvius, for instance, have to say about the spatial needs of supercomputers? Would De architectura have contained an extra chapter about the square-footage of rural data centers if Vitruvius had been alive today – and, if so, what might it have said? For that matter, what if Rem Koolhaas had written Delirious New York during an age in which that city's major IT operations took place inside windowless, hydroelectrically powered warehouses in the Hudson Valley (or even Québec)? What spatial lessons might these ex-metropolitan data warehouses entail? Further, if, say, SOM were to design every governmental server farm in the United States, and if those server farms were then used to store sensitive information about the habits of U.S. citizens – what international calls they make, what books they buy from Barnes & Noble, what movies they rent from Netflix or even Sugar DVD – would that represent an ethical compromise? Is it morally right to design spatial envelopes for server farms, when the computers housed therein might be used in invasive ways? 2) I'm actually quite fascinated by the idea that the NSA has been looking "to decentralize its computing resources and tap regions with ample supplies of lower-cost electricity." This comes with fascinating implications – for instance, that some random town in Wisconsin (or, of course, Utah) might unknowingly become host to several dozen supercomputers of extraordinary strategic importance in the pursuit of national security... even though the only real evidence that this undeclared hardware exists will be a mysterious strain on the town's evening power supply. Each night at 8:30 the streetlights dim: it's the harddrives cooling down, or warming up, or turning over for maintenance. Like some weird new version of Salem's Lot, in which the anonymous presence haunting your town is actually a government server farm stored inside an old factory by the river, surrounded by cyclone fencing... After all, "regions with ample supplies of lower-cost electricity" might very well include towns in the Rockies, in Alaska, and out on the tornado-prone plains – and so, similar to Tom Vanderbilt's exploration of decommissioned nuclear silos in the horizon-spanning ranchlands of the great American nowhere, there might yet be future spatial archaeologies written about military data centers, surveillance data centers, wiretapping data centers, any sort of top secret data center that once hummed away somewhere in the darkness, perhaps even disguised as suburban houses. That apparently empty bungalow you see at the end of your street, like the opening scene of War Games, in other words, is actually full of harddrives; it's not Ed Gein coming home at 3am, strange packages in hand, it's an Information Assurance officer coming back to check the fuses. It's the informational gothic: the IT needs of Homeland Security narratively transformed into a new genre of mysterious blackouts and spatial paranoia. (Originally spotted via @stevesilberman).

I've just been reading an awesome new publication by students from the Bartlett School of Architecture's Unit 11, whose instructors are Mark Smout and Laura Allen of Augmented Landscapes fame.  [Image: The "House of Drink" by Margaret Bursa, Unit 11]. [Image: The "House of Drink" by Margaret Bursa, Unit 11].The publication itself is called ELEVEN, and it will apparently be published twice a year; this particular issue has the running theme of "Field Operations." While there is some brief theorizing about "guidelines of actions," and how those guidelines can frame architectural space, it's the individual projects that deserve attention. What's inside?  [Images: A display of Unit 11 projects; all images by Stonehouse Photographic]. [Images: A display of Unit 11 projects; all images by Stonehouse Photographic].There are "prophylactic wars and military utopias" by Luke Pearson (Pearson's work, of course, having been previously explored on BLDGBLOG); a hydrological reengineering of the U.S./Mexico border by Joel Geoghegan; and weird 3D scans of the abyss, via the opiated writings of Thomas de Quincey, by Rae Whittow-Williams: ...the aim of the project translates the various hallucinations of Thomas De Quincey into the envelope of [an] existing house. Each environment is developed using differing techniques and processes of collaging space, forced perspective and iterative modelling in order to create a series of scale-less and absorbing hallucinatory spaces. There are resonating buildings full of "drone pipes" and "sound bags" by Chris Wilkinson; the "rapid prototyping of a hyper-real Manhattan" by Alex Kirkwood; replicated replicas; Fabergé menageries; and much more.  [Image: From "The Survey of London" by Will Jefferies, Unit 11]. [Image: From "The Survey of London" by Will Jefferies, Unit 11].It only costs £3, and it includes a foreword by Sam Jacob. Jacob suggests, praising the students for their initiative in starting the publication, that "we can argue – despite what Tafuri says – for the importance of architects writing their own histories, publishing their own agendas and documenting their own landscapes. By confusing (or fusing) production, reproduction and dissemination with the practice of architecture an expanded, speculative field opens up." You can buy it at the Architectural Association, RIBA, and Magma, as well as via smoutallen.com.

[Image: Issue #1 of New Geographies]. [Image: Issue #1 of New Geographies].The recently launched Harvard journal New Geographies will be celebrating their second issue – which is actually numbered one – and it's about zero. What happens when architecture, the global economy, and the trade in ideas – when culture itself – hits what the editors called a "zero point," after which everything can be reformatted, begun again, launched in new directions and through entirely new geographies? After all, they suggest, there are zero moments everywhere – Ground Zero, zero carbon, cities from zero, zero-g tourism, and so on. The new issue specifically explores "possibilities AFTER crises, AFTER mapping, and AFTER signature architectures," we read. You can find out more on Tuesday, 7 July, at the Storefront for Art and Architecture in New York.

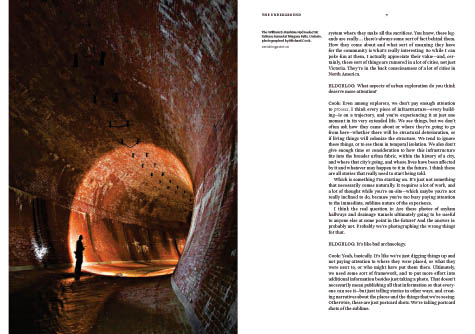

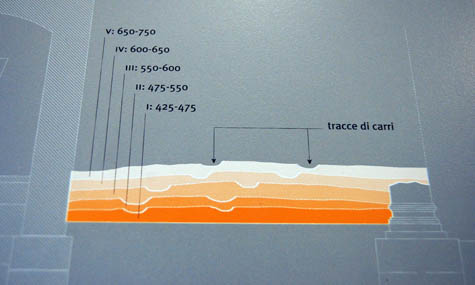

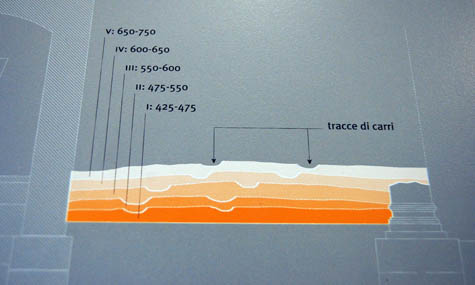

[Image: A Greenland ice-core at the Hayden Planetarium; for further reading, visit the U.S. National Ice Core Laboratory. Photo by Planet Taylor, used under a Creative Commons license].Note: This is a guest post by Nicola Twilley. [Image: A Greenland ice-core at the Hayden Planetarium; for further reading, visit the U.S. National Ice Core Laboratory. Photo by Planet Taylor, used under a Creative Commons license].Note: This is a guest post by Nicola Twilley.The Crypta Balbi is a relatively recent, low-profile addition to Rome's museum compendium. It's billed variously—and confusingly—as a museum of archaeology, a museum of ancient Rome, and a museum of the Dark Ages. All of these descriptions are, in fact, cumulatively accurate, because the site is actually a city-block-sized core sample of Rome, threaded through with staircases, tunnels, and elevated walkways for visitors. Crypta Balbi is located in an irregular pentagonal plot in the Campus Martius, an area that, unlike many regions in the ancient city, remained largely inhabited through the Middle Ages. In fact, according to Filippo Coarelli's authoritative Rome and Environs: An Archaeological Guide, the Campus Martius was originally supposed to be kept free of buildings altogether and "reserved for military and athletic exercises." However, historian Suetonius describes the city’s gradual encroachment, explaining that: "During his reign Augustus often encouraged the leading men of Rome to adorn the city with new monuments or to restore and embellish old ones."  [Image: A satellite view of the city-block core sample, via Google Maps]. [Image: A satellite view of the city-block core sample, via Google Maps].As a successful military general and favored member of Augustus's entourage, L. Cornelius Balbus the Younger stepped up to the plate, building a theater and attached crypta—a rectangular porticoed walkway where the theater's scenery could be stored and around which the public might stroll, protected from the elements. Apparently, the Balbi Theater's grand opening in 13 BC took place during one of the Tiber's regular floods—meaning that it was, briefly, only accessible by boat. Nonetheless, the Theater and Crypta thrived, and they are depicted intact on a chunk of the Severan Forma Urbis, an amazing 60'-x-43' incised marble map of the city created for public display in 203 AD. Eventually, Rome’s earthquakes, fires, barbarian raids, and radical population shrinkage (from a million people in 367 AD to just 400,000 less than century later) combined with architectural re-use and the passage of time to take their toll. There isn't much of the original Crypta left to see—a reconstructed stucco arch, and the massive travertine and tufa walls that now serve as foundations for modern houses in Via delle Botteghe Oscure and Via dei Delfini.  [Image: A fragment of the Forma Urbis, showing the Balbi Theater. For more on the Forma Urbis, visit the seemingly great but non-Mac-friendly Stanford Digital Forma Urbis Romae project]. [Image: A fragment of the Forma Urbis, showing the Balbi Theater. For more on the Forma Urbis, visit the seemingly great but non-Mac-friendly Stanford Digital Forma Urbis Romae project].However, layered above the Crypta's original floor plan are traces of this city block's shifting usage—a condensed narrative of Rome's destruction, accretion, and evolution. It is this series of transformations and reuses of both the Crypta and the urban space it occupies, rather than the fragmentary ancient ruins, that the museum aims to make visible. Like a series of stills from an impossible time-lapse film, the visitor who descends to the basement or climbs to the third floor can see this awkward cuboid chunk of city ruined, reshaped, reused, and reoriented over two thousand years of urban history. Equally amazing are the expansive historical detours prompted by even trace elements in the urban core sample. For example, as early as the time of Hadrian, a " monumental" public latrine was inserted into a section of the Crypta. From the quantity of copper coins that fell, and weren't worth recovering, archaeologists have extrapolated the amount of coinage in circulation in Western Europe during the latrine's life-span. (Astonishingly, it was only in the 19th century that small change was to be this common again in Western Europe).  [Image: Museum display panel diagramming five distinct road levels wandering across the Crypta's ruins (apologies for the quick snapshot)]. [Image: Museum display panel diagramming five distinct road levels wandering across the Crypta's ruins (apologies for the quick snapshot)].Two centuries later and a few feet higher, two graves bear witness to a city in ruins between the 5th and 7th centuries, as the prohibition against burial within city walls lapsed, and the dead were buried singly in abandoned buildings or beside roads. Ironically, in a museum that preserves the urban structures of each era equally, during the medieval period the Crypta actually housed one of the city's largest lime-kilns, where the marble inscriptions, statues, and building blocks of classical Rome were brought to be crushed and melted down into lime (a key ingredient in the cement needed to build the city's new Christian architecture). In the 1940s, the convent that had occupied the site for the past four hundred years was demolished for a planned new Mussolini-era construction, which thankfully never materialized. Finally, in the 1980s, the Soprintendenza archeologica di Roma authorized the excavation of the abandoned city block; and, in 2002, the northwest corner was opened to the public, even as work continues on the rest of the site.  [Image: An interior view of the Crypta Balbi]. [Image: An interior view of the Crypta Balbi].Aside from the execution, which is excellent, the very idea of a museum built into an urban core sample—a stratigraphic investigation of the shifting use of space over time—is incredibly exciting to me. Imagine a similar hollowing-out of urban space in Istanbul, Cairo, or Paris—residents as disoriented as tourists as they clamber through the hidden foundations and forms woven underneath and around their own city. In New York, this might even be an idea whose time has come: as The New Yorker pointed out in December 2008, the expiration of a residential construction tax-abatement law encouraged builders to dig foundation trenches early, so as to secure better financing, but the subsequent recession has put many of these projects on hold, semi-permanently. "What will become of the pits?" asks Nick Paumgarten, speculating that they could turn into "half-wild swimming holes, like the granite quarries of New England" or even "urban tar pits, entrapping and preserving in garbage and white brick dust the occasional unlucky passerby." These are both attractive ideas, but with a little expenditure on zip-lines, elevated walkways, and interpretative signage, visitors could circulate around several millennia of Manhattan's history, from the collision of the North African and American continental plates to the tangled evolution of New York's water mains, via retreating glaciers and the housing bubble. Meanwhile, back in Rome and less than a mile away from the Crypta, engineers have teamed up with the Soprintendenza to sink several new urban cores, this time in the guise of excavating the elevator and escalator shafts for a new subway line. Angelo Bottini, director of the Soprintendenza, can hardly hide his excitement, telling the Wall Street Journal that, under usual circumstances, "We never get to dig in the center of Rome." Sadly, it seems as though most of the finds will be documented and then destroyed, due to a shortage of museum space and the already astronomical construction costs (an estimated $375 million for one mile of track in the city center). But how amazing would it be if the new subway station walkways and escalator shafts could themselves become Crypta Balbi-like museums of buried stratigraphy? Rome would be riddled with urban cores, awestruck tourists ascending and descending through sampled spatial histories across the city. Meanwhile the Sistine Chapel lies miraculously empty... [Previous guest posts by Nicola Twilley include The Tree Museum, The Water Menu, Atmospheric Intoxication, and Park Stories].

|

|

[Image: The Bat Spiral by friend and company].

[Image: The Bat Spiral by friend and company].

[Image: "

[Image: " [Image: The Pantheon, photographed by

[Image: The Pantheon, photographed by  [Image: A human blink, via

[Image: A human blink, via  [Image: The dimensions of an island: a sign posted on

[Image: The dimensions of an island: a sign posted on  [Image: The gridded rails of a lost interior,

[Image: The gridded rails of a lost interior,  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: Sydney's

[Image: Sydney's  [Image: This season's lecture schedule at Sydney's Tusculum;

[Image: This season's lecture schedule at Sydney's Tusculum;  Launching just today is an awesome new ideas competition called

Launching just today is an awesome new ideas competition called  Co-sponsored by Inhabitat, the contest's judges are

Co-sponsored by Inhabitat, the contest's judges are  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: An illustration by

[Image: An illustration by  [Images: Two original comic strips by

[Images: Two original comic strips by  [Image: An illustration by

[Image: An illustration by

[Images: Spreads from

[Images: Spreads from  [Image: A spread from

[Image: A spread from  [Image: The beginning of the Further Reading list, from

[Image: The beginning of the Further Reading list, from  [Image: The Autographs page, from

[Image: The Autographs page, from  [Image: A spread from

[Image: A spread from  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: The "House of Drink" by

[Image: The "House of Drink" by  [Images: A display of

[Images: A display of  [Image: From "The Survey of London" by Will Jefferies,

[Image: From "The Survey of London" by Will Jefferies,  [Image: Issue #1 of

[Image: Issue #1 of  [Image: A Greenland ice-core at the

[Image: A Greenland ice-core at the  [Image: A satellite view of the city-block core sample, via

[Image: A satellite view of the city-block core sample, via  [Image: A fragment of the Forma Urbis, showing the Balbi Theater. For more on the Forma Urbis, visit the seemingly great but non-Mac-friendly

[Image: A fragment of the Forma Urbis, showing the Balbi Theater. For more on the Forma Urbis, visit the seemingly great but non-Mac-friendly  [Image: Museum display panel diagramming five distinct road levels wandering across the Crypta's ruins (apologies for the quick snapshot)].

[Image: Museum display panel diagramming five distinct road levels wandering across the Crypta's ruins (apologies for the quick snapshot)]. [Image: An interior view of the

[Image: An interior view of the