|

|

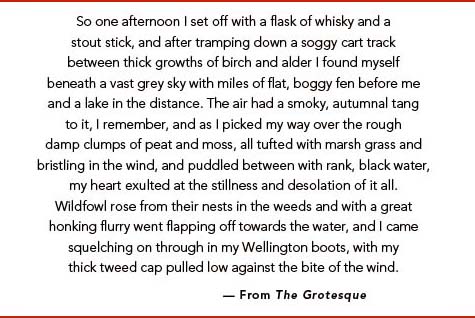

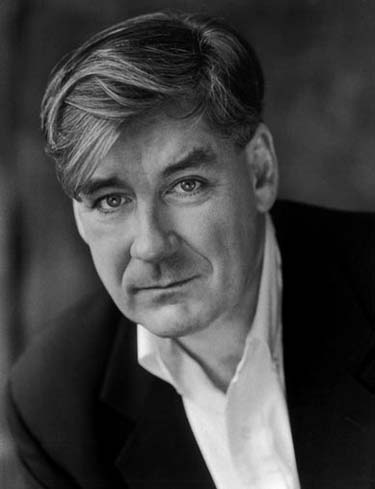

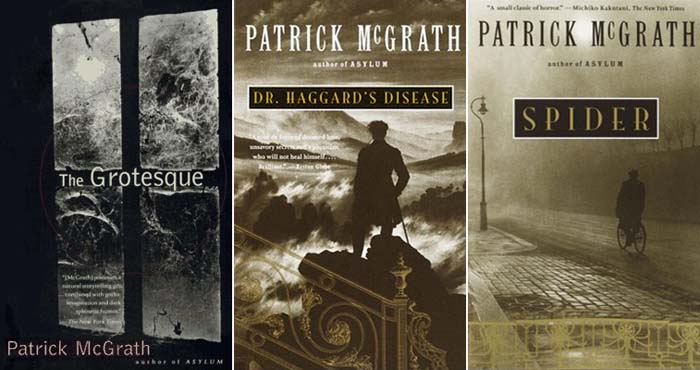

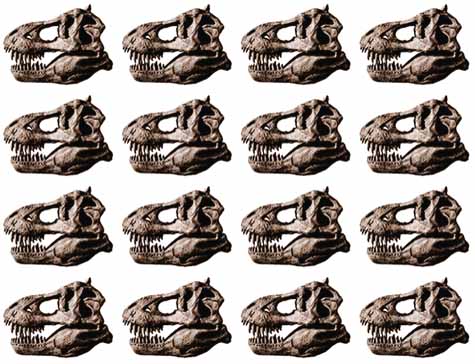

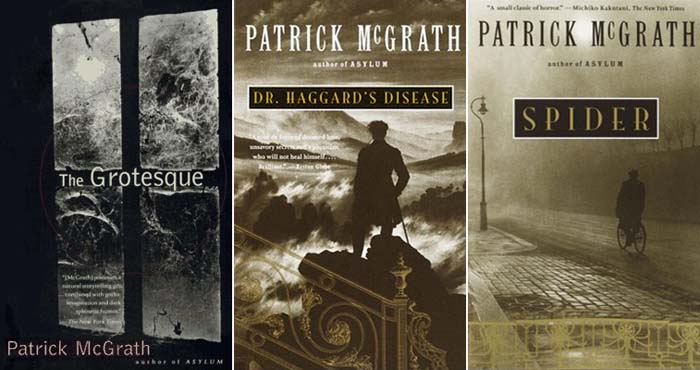

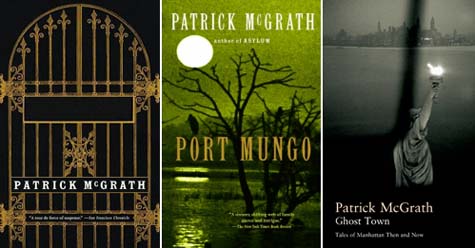

The novels of Patrick McGrath are often described as Gothic. They unfold across foggy landscapes and rolling moors, on marshes dotted with isolated houses and dead trees. There is a lot of rain. McGrath's characters are frequently deformed, crippled, mad, or somehow undefined, both psychologically and sexually; they are sinister, if naive, and quietly aggressive, weaving conspiratorial plots around one another with a tightness and an intricacy, and a psychological intensity, till something dreadful occurs – and the book then lurches on to its brutal and unhappy ending. Amidst tropical swamps and London graveyards, crumbling barns and basements, operating theaters and unused bedrooms, we find incest, murder, and suicide – as well as the creeping, subterranean shadows of mold and rot. But it is the settings, and not the plots, of Patrick McGrath's novels that led me to speak with him for BLDGBLOG. For those brackish marshes and dust-filled hospital wards are extraordinarily well-described; indeed, McGrath's eye is intimidating in its detail, supplying information across the senses, giving us the taste, smell, and sound of his fictional worlds, in beautifully crafted sentences. His landscapes are precise, vivid, and worth re-reading.  A question often asked on this website is: what do novelists, artists, and filmmakers want from landscape and the built environment? More specifically, how can architecture assist a writer as he or she constructs a novel's storyline? Are certain types of buildings more conducive to one kind of plot than to another? And what about landscape? How does landscape lend itself to literary effect – and could landscape architects actually learn something about the drama of designed space by turning to a novel instead of to a work of theory? To the work of Patrick McGrath, for instance? In the following interview, Patrick McGrath talks to BLDGBLOG about Romanticism, the Sublime, and the origins of Gothic literature, from Mary Shelley's Alpine wastes to the forests of Bram Stoker, by way of Edgar Allan Poe and the frozen seas of the Antarctic. We discuss David Lynch, The Sheltering Sky, the architecture of psychiatric institutions – where cell doors always open outward – and the spectacle of unfinished castles soaked with rain on the British moors. We pass through mountains, abbeys, and malarial swamplands, referring to Joseph Conrad, amateur paleontology, and the featureless voids of the Sahara. We spoke by telephone.  [Image: Novelist Patrick McGrath].• • •BLDGBLOG [Image: Novelist Patrick McGrath].• • •BLDGBLOG: First, on the most basic level, could you talk about what makes a landscape "Gothic"? Is it the weather, the landforms, the isolation, the plantlife…? Further, in your own work, what is it, on a psychological level, that unites, say, the crooked and leafless trees of the British moors with the coastal swamps of Honduras? Patrick McGrath: Not an easy question to answer! As you point out, a landscape could be tropical – or it could be Arctic, and it could still have those qualities that we might consider Gothic. It’s hard to know just what these landscapes have in common. I suppose we have to go back to the origins of Romanticism, and to Edmund Burke's book on the Sublime, and look at his notions of the horrid and the terrible. There were landscapes that emotionally aroused the people of that time – but because of their what? Their magnificence in some way. The sheer scope and grandeur of the high mountains – the Alps which Mary Shelley described very powerfully in Frankenstein – or the eastern European landscape in Bram Stoker's Dracula: the loneliness and the remoteness of those mountains, the density of the forests, the fact that there are very few human beings there. Nature dwarfs humanity in such landscapes. And that will arouse the sense of awe that is made particularly dramatic use of in Romantic and Gothic literature. Then, at the other end of the scale, we have a tropical landscape such as Conrad’s Congo in Heart of Darkness where it’s almost the reverse: it’s the constrictiveness and the fecundity of nature, the way it presses in on all sides. Everything is decaying. And decay, of course, is a central concept in the Gothic. So when you have tropical vegetation you do have a sense of ooze and rot – of swampiness. BLDGBLOG: You mentioned that certain landscapes might have been "emotionally arousing" for the people of that era – but this implies that what makes a landscape emotionally arousing will change from generation to generation. If that’s the case, might something altogether different be considered Gothic or Romantic today? Have you noticed a kind of historical shift in the types of landscape that fit into the Gothic canon? McGrath: My first thought is: not so much of landscape – but let’s say in the view of the city. My second novel, Spider, was inspired by a book of photos by Bill Brandt. He captured the seedy, ill-lit character of the East End of London of the 1930s in such powerfully human character – illicit liaisons on wet cobbled streets, toothy barmaids in grotty pubs, pulling pints for sardonic men in cloth caps – that I was at once inspired to find a story there. But I do think the Victorian slum – the dark, rather shadowy streets that have a sort of sinister and rather threatening feel to them – could be replaced by the blandness of a suburb. I’m thinking of what David Lynch did in Blue Velvet, with a scene of apparent utter normality. Think of the opening scene where a man is watering his garden and everything seems, well, perfect in that neat and orderly suburban way and yet his camera then goes beneath the grass and we see all sorts of forms of life that are slimy and grotesque and that aren’t apparent in that hygienic world above. So there may be something in that: the suburb as the most Gothic of sites. Think of the work, say, of Gregory Crewdson. BLDGBLOG: That raises the question of what sorts of architecture pop up most frequently in Gothic literature: usually English manor houses, church ruins, forgotten attics and so on. Why are certain types of buildings more conducive to one type of storyline and not others? McGrath: I think you’d have to say that there are two questions here. There’s the conventional, stereotypical Gothic site which tends to be a lonely house high on a hill, probably Victorian, with turrets and the possibility of secret passageways and cellars and attics – places of obscurity, places where the past somehow resides. You know, houses of secrets. These sites, in turn, would have grown out of the more traditional Gothic architectures – basically the ruins of monasteries and abbeys and convents and such, which dotted the British landscape in the 18th century, after the Reformation. Those first aroused the taste for ruins, and that was the origin of the Gothic. That would be basically a medieval architecture – in ruins, as I say, because of what Henry VIII did to the English church in the 16th century. So those were the places where people like Horace Walpole set their fiction, because the buildings were in such a state of decrepitude. I think anything that sort of relates to these large, broken down, dilapidated structures would arouse the Gothic effect.   [Images: The Abbey in the Oakwood, 1809-10, and Cloister Cemetery in the Snow, 1817-19, by Caspar David Friedrich].BLDGBLOG [Images: The Abbey in the Oakwood, 1809-10, and Cloister Cemetery in the Snow, 1817-19, by Caspar David Friedrich].BLDGBLOG: Interestingly, though, in the work of J.G. Ballard, you get the same sort of psychological atmosphere – of perversion, violence, and dread – from a totally different kind of built environment: instead of crumbling manor houses, you have corporate office parks in the south of France, or even British shopping malls. McGrath: Absolutely – and that was going to be the second part of my answer. There is the old Gothic, which does have a very definite architectural style that comes out of the structures of the Middle Ages, as these became ruins and gave off a sense of ghostliness and evil and menace. But then there is what you might call, I don’t know, a new Gothic, where the particular trappings of the old Gothic, the particular stylistic characteristics, are not necessary to produce the same sorts of effects – the feelings of dread, constriction, obscurity, transgression. You can get those from inner city projects, for example, or even a little neat rowhouse. There was an early Ian McEwan novel, The Cement Garden, where all sorts of perverse wickedness was going on but in a very sort of unmemorable little house, in a street of very similar houses, none of which would particularly smack of evil. Although I did notice, when I was re-reading it, that he uses a little crenellation detail in the architecture of one of these absolutely anonymous little houses. He’s just touching-in this faint hint of the Gothic – as though to say: this is a child of something out of Ann Radcliffe, some decaying monastery in which an aristocrat pursues a maiden in the depths of the night.  BLDGBLOG BLDGBLOG: I’m curious if there are any real buildings that you have in mind when you’re describing places like Drogo Hall or Crook Manor. Put another way, could someone ever do a kind of Patrick McGrathian architectural tour, or heritage walk, visiting sites that have inspired your fiction? Where would that tour take them? McGrath: [ laughs] Good question. I don’t quite know where I get them from. In part from the imagination, in part from books, books I’ve got around the place with photographs or paintings of buildings, some of which I’ve observed and remembered. There’s a house called Crook in my first novel, The Grotesque. I found a lovely little book in a second-hand bookstore in New York, called The Manor Houses of England, and I simply leafed through it, picking up details here and there – not only architectural details, but verbal details. The way that aspects of architecture are described – the sorts of terms that are used – can be as much a part of the creation of a building in fiction as a clear, purely visual picture in your mind. You catch a nice phrase that’s used to describe, I don’t know, a Jacobean staircase or a particular piece of detailing or masonry – and you fling it in because it sounds good, rather than just because it evokes a particular image. But I don’t think there’s a pattern. They’re usually curious amalgams that I put together in my imagination. BLDGBLOG: I noticed one day that there is a real Castle Drogo. Architecturally, how much of that was an influence on your descriptions of Drogo Hall? Or did you just use the name? McGrath: It was basically just the name. Castle Drogo’s somewhere down in the West Country, I can’t remember where – I think it looks over Dartmoor. It was built in, I think, the early twentieth century by some rich industrialist, as I remember, who wanted to have a main building with two wings. But then his son was killed in WWI, and he’d only built one wing of the castle. He grew so despondent that he never built the second wing. All the life had gone out of him. So it’s an incomplete structure. It was also essentially an ersatz thing – it wasn’t a proper castle. It was an Edwardian idea of a castle – of which there are many in Britain, of course. But it was the name; the name was very powerful: Drogo. So I pinched the name and gave it to a building that I largely invented out on the Lambeth Marshes. And, again, the Lambeth Marshes as I describe them don’t really have any resemblance to the Lambeth Marshes as they existed in the 18th century. I mean, I sort of put a Dartmoor on the south of the Thames – and I don’t think it was like that! [ laughter] BLDGBLOG: Well, it works, so... McGrath: It works – and that’s all you want.  [Images: Castle Drogo].BLDGBLOG [Images: Castle Drogo].BLDGBLOG: Have you read The Emigrants by W.G. Sebald? One of the stories is partially set in an old, sprawling psychiatric hospital in the forests of New York state. Near Syracuse, I think, or maybe Ithaca. The narrator explains that his uncle once committed himself there voluntarily to undergo electroshock therapy, basically as a way to erase painful memories from some time spent in the Sahara south of Cairo. McGrath: Now, this is very, very interesting – I’ve read Sebald, but not that particular book. In fact, I’ve just finished a novel which is set in Manhattan and the last couple of chapters are set in a mental hospital in northern New York state. And I had no idea about Sebald using that location – and I didn’t really know about the Victorian institutions you described. What I did was I took an institution from northern Ontario where I worked when I first came over to North America, and it was very unlike a Victorian institution. It was sort of like a blockhouse – like a penitentiary. And so what I’ve done is I’ve sort of plonked that down in upstate New York – but I might have to rethink how I’ve done that based on what you’ve just said. But this is great to know – I’ve still got time to tear that chapter apart. BLDGBLOG: Well, some of those hospitals – these big, Gothic complexes – have actually been demolished. But in other cases, they’ve been transformed into apartments and condominiums – McGrath: Yes, that’s happening in England, too. I visited old Victorian asylums there that have outlived their usefulness and are now being converted into apartments.  [Image: The Hudson River State Hospital, beautifully photographed by Kirkbridebuildings.com. The rest of that site – especially the other hospitals – is well worth checking out].BLDGBLOG [Image: The Hudson River State Hospital, beautifully photographed by Kirkbridebuildings.com. The rest of that site – especially the other hospitals – is well worth checking out].BLDGBLOG: Returning to the question of landscape, the natural environments in your work are extraordinarily well-described; in fact, there are parts of Asylum that strike me as literal exemplars of superb landscape description. I’d love to know more about how you work: if you actually visit specific locations, driving up to the moors or through the hills of New England, to capture your descriptions on the spot; or if you work from memory, or from imagination, or even from other books of photographs. McGrath: There have been times when I’ve gone to a place. When I went down to Belize, for instance, and saw what Belize City looks like – the shacks lurching unsteadily over the river, the mangrove swamps and so forth – that just told me, instantly, that here I had the setting of a novel. I took a lot of photos and then basically used what I’d seen. Other times, I just sort of invent it. I remember when I was writing The Grotesque, I had the Berkshire marshes in there, and I’d been out of England for many years at that point and somebody pointed out to me that, in fact, there are no marshes in Berkshire – BLDGBLOG: [ laughs] McGrath: – but by then it was too late. I needed there to be marshes and I wanted it to be Berkshire, for some reason, and so there it was: a completely nonexistent landscape had sprung to life. I don't know, I look at things and a lot of it comes from reading. I discover details that, for example, in prisons and asylums you will always have the doors opening outwards so that whoever is incarcerated behind that door won’t be able to blockade themselves inside the room. Little details like that give the character of an institution and can be very evocative on the page.  BLDGBLOG BLDGBLOG: I'm also curious about weather and climate. For instance, a wet climate – with thunderstorms, humidity, and damp – seems to play a major, arguably indispensable, role in the Gothic imagination. Your own novels illustrate this point quite well: from rain-soaked country homes to the Lambeth marshes, from coastal fishing towns to Central American swamps. But can aridity ever be Gothic? In other words, if the constant presence of moisture contributes to a malarial atmosphere of decay, mold, infestation, and disease, might there be a whole other world of psychological implications in a climate where things don't decay – where there is no mold, where bodies turn to leather and everything can be preserved? Is indefinite preservation perhaps a Gothic horror of its own? McGrath: Aridity does interest me. It’s an unusual application of the Gothic mood. You usually think of northern European or north American climates and landscapes, but that’s merely because, traditionally, that’s where these sorts of stories have been set. But I can very well imagine aridity being a place, or a site, for such a story. I think you could safely say that one of the themes of the Gothic is the sins of the father being visited upon the sons – in other words, there is no escaping the past. The past will always haunt the present. And this is certainly true of Gothic stories that are set in crumbling old houses: there's always some piece of evil that has occurred in a previous generation that will work itself out on the current generation. So that continuation – or persistence – of the past is what you’re expressing: it’s the skeleton that can’t be disposed of. But I’m trying to think if I know of a Gothic tale set in a desert, and the only thing I can come up with is... I think it's an old Erich von Stroheim movie. It might be called Greed? There's a man who has, somehow or another, wound up handcuffed to his companion – and the companion has died. This is in the quest for gold. Somehow or another their greed has got them into an impossible situation: they're handcuffed, the companion has died, and so we have a man crawling across the desert handcuffed to a corpse. It being a desert, of course, he's doomed. But that's a very powerful image of an utterly arid landscape. In the spirit of a new Gothic, one that isn't dependent on very particular types of landscape or architecture, you could certainly exploit an arid landscape in order to create a condition of extreme thirst, extreme solitude, extreme desperation – all of which would be appropriate states of mind for a Gothic story. I just can't think of many examples. BLDGBLOG: It never really occurred to me to refer to this book as "Gothic" before, but there's The Sheltering Sky by Paul Bowles – where you see people completely destroyed by the desert. The Sahara is presented as this strangely dark landscape, something that they can't comprehend culturally and they can't survive physically. McGrath: Whether you could get away with calling that Gothic, I don’t know! But, certainly, there is horror in that environment. It does have that in common with the Gothic. You can't have the Gothic without horror, and the desert is a place where, you’d think, horror is always close at hand. BLDGBLOG: Meanwhile, some of the earliest Gothic fiction was actually polar – Mary Shelley's Arctic chase in Frankenstein is an obvious example. I'm curious if glacial landscapes and frozen seas attract you? Might there someday be a kind of Arctic Port Mungo? McGrath: Well, again, in the novel that I've just finished, I wanted to take my character, when he's pretty much spiraled down as far as he can get in New York City, to a place of snow. And there are all sorts of precedents for this. Frankenstein, as you say, begins up in the Arctic Sea – and ends there. I think the final image is Frankenstein pursuing his creature across the frozen waste – a vast white landscape. There's also Poe's The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym, which comes to a place of great whiteness; and, almost contemporary with that, is Melville’s white whale. There is something about whiteness that is almost identical to blackness in terms of what it can evoke. I think it must be about featurelessness: the horror that comes of there being nothing there. It's a white nothing instead of a black nothing. But the absence of color would suggest a kind of emptiness, a draining of life and meaning. A void. And the Gothic is very fond of a void. And Melville was certainly onto that. I mean, you can’t help but see that the white whale is really just a blank screen onto which Ahab has projected all sorts of powerful and twisted emotions – but, in itself, it is merely a screen. Melville's possibly suggesting that all of nature is just such a blank screen, and that it is the business of humans to project meaning onto nature, that meaning is not inherent, is an idea that I think we can comfortably live with now; but, I think, in the 19th century, it was probably a great deal more threatening to God-fearing people.  [Image: The Sea of Ice, 1824, by Caspar David Friedrich].BLDGBLOG [Image: The Sea of Ice, 1824, by Caspar David Friedrich].BLDGBLOG: One of the most striking images I've read in years is actually your character Hugo Coal, from The Grotesque, assembling his dinosaur skeleton in the family barn. I’d love to hear your thoughts about what went into that image – but also what you think about the human encounter with prehistoric monstrosity: with dinosaur bones, and marine fossils, and the utter strangeness of the earth's inhuman past. McGrath: What interested me – before I'd even thought through aspects of deep time, and what that means – was that a man could go to Africa and collect a bunch of bones and crate them up and bring them back, and then spend the rest of his life trying to see what fitted where. This may be completely implausible, in terms of paleontology, but I just liked the notion of Sir Hugo sitting there in his barn, year in, year out, trying to make a pattern, to make a structure – and continuing to get it wrong. It seemed, somehow, very much in the spirit of human endeavors to discover the truth, or to figure out how nature works – or even, within that book, to get an answer to the mystery of who killed Sidney. It was to do with the fallibility of knowledge that was contained within this enterprise of getting the bones to fit – and they won't! [ laughs] There's always a bit left over, or something that won't go where it’s supposed to go. So that was the aspect, the epistemological aspect, of reconstructing a skeleton that first fascinated me. Then there was the notion of this thing coming from deep in the past and being now extinct – from so deep in the past that it no longer had any place on this earth – and the suggestion that Sir Hugo, in a sense, was the same. He, too, was a dinosaur; his day, as a representative of a certain social class, was past. But the first impulse that I had was that this was a carnivorous creature. This wasn't a gentle herbivore Hugo's got there. This was a creature of enormous violence and absolute rapacity, capable of tearing its prey to pieces, and I wanted to suggest that those sorts of implicit violent energies were now swirling about this old country house. BLDGBLOG: In some ways, though, it seems like the contemplation of the earth's biological past lends itself well to the Gothic mood – but contemplating, say, the earth's geological past just doesn't have the same psychological impact. For some reason, rocks just aren't very Gothic. McGrath: Well, I remember the way that Conrad handles the river in Heart of Darkness: he speaks of the journey that Marlow takes to get to Kurtz as being a journey through, or deeper into, the geological history of Africa. I forget how he does it, but he gives you the sense that, as the boat moves up the river, it is also descending through eons of time. So there is almost a sense of a geological regression occurring as Marlow moves toward a man who has committed an act of enormous moral regression. Everything is about a movement downwards in that book. I’d say that he employs geological descent to mirror a moral descent. BLDGBLOG: Of course, there's also Hugo Coal’s surname: coal, a geological product. McGrath: There you are. Absolutely. That was no accident. Again, I'm referring to deep layers of what once had been wood, and that now, through the operation of time and pressure, is something quite different. BLDGBLOG: Finally, I'd like to ask you about islands. You're from England, with a home in Manhattan, and you’ve lived on "a remote island in the north Pacific." Interestingly, though, your work doesn't include a lot of islands – indeed, there are very few scenes at sea. Do the Gothic possibilities of islands, or archipelagos, have any literary interest for you? McGrath: Well, that's true. I don't know why that should be. I've put people by the water often enough – a lot of my people seem to stand in high places gazing out to sea – but the notion of an island as a... I suppose the island gives you the possibility of a closed community – and that's always a good site to play out a story in. You can just say that the world doesn't extend beyond the borders I've imposed upon it. I suppose the use of a village is a sort of island. The last book I’ve done is set in Manhattan almost exclusively, but... I've never sort of literally done an island. I think every novelist – unless you're Dickens, maybe, where you just want to give a great sweep of an entire society – finds a way of creating islands, or social islands, anyway. The family is a sort of island. A prison, an asylum, is a sort of island. A town can be a sort of island. I mean, every novel has to limit its scope geographically and socially, so I suppose we create islands – but I've never particularly been drawn to an island itself. Though I do have a novel somewhere in the back of my head set on an island in the Mediterranean. I suppose the answer is: I don't see the need for an island in itself, when the only point to an island would seem to be to draw a circle around a community. Unless it was the notion of being cut-off... That would be a good reason to make an island. You know, where the weather closes in and your people have no way of escape. I can see that being a way you might want to use an island. But I just haven't felt the need yet.  [Image: Monk by the Sea, 1809, by Caspar David Friedrich].BLDGBLOG [Image: Monk by the Sea, 1809, by Caspar David Friedrich].BLDGBLOG: As I mentioned, your bio refers to a "remote island in the north Pacific." I'm just wondering where exactly that was? McGrath: There's a group of islands called the Queen Charlottes. They're off the northwest coast of British Columbia. If you were to find Prince Rupert on the map, you would then just go due west about 80 miles, and they're just south of the Alaskan panhandle. There are two main islands: Moresby and Graham. Moresby is uninhabited and Graham has, oh, two or three little towns. That's where I lived a few years. I was a schoolteacher back in those days, and I'd been living in Vancouver, and I wanted to get out of the city, basically. So I got a job teaching there, and, while I was there, I basically gave up teaching and built a cabin and declared myself a writer. That was the beginning. • • •BLDGBLOG would like to thank Patrick McGrath for taking the time to have this conversation – which he and I both hope to continue in a few months' time: so watch out for another interview with Patrick McGrath here on BLDGBLOG, to be posted, I hope, this winter. Meanwhile, Asylum, The Grotesque, and Spider are all great places to start, if you're looking for an introduction to Patrick McGrath's work. Spider, of course, was recently filmed by David Cronenberg. A new novel, meanwhile, called Trauma, is due out in April 2008. Finally, this PDF contains a much longer, and older, interview with McGrath (in which he describes the grotesque as "things beginning to merge, things becoming undifferentiated" – the grotesque is a "breakdown, in every dimension that I could imagine, in the organic, in the social, in the sexual, in the natural"). Briefly, then, it's interesting to point out that one of the manifestos mentioned in the previous post discusses the grotesque in terms of monstrosity, beauty, and architecture.

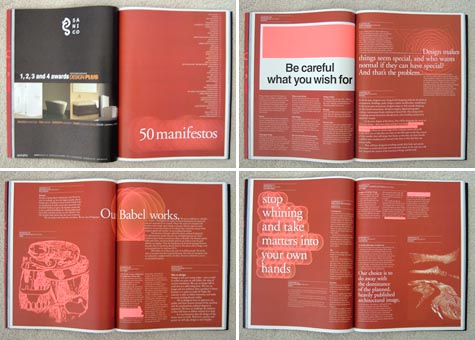

For its landmark 50th issue, British architecture and design magazine Icon put out a call for manifestos "from 50 of the most influential people in architecture and design" today.  [Image: The cover of Icon #50]. [Image: The cover of Icon #50].The manifestants – manifestators? manifestees? manifestors? – "include Rem Koolhaas, John Maeda, Zaha Hadid, Hussein Chalayan, Jasper Morrison, Peter Eisenman, Peter Saville, Foreign Office Architects, Joep van Lieshout, the Bouroullecs and Ken Livingstone," the " rebel mayor" of London. In Livingstone's case, he, Richard Rogers, and Peter Bishop have basically submitted a new press release for Design for London ("Design for London wants London to be a city that works for all its people, for its economy and for the environment"); in Zaha Hadid's case, she sent in what appears to be a three-part digital rendering of... London? From the air? Gone topographically sinuous and structurally cubic? Or perhaps she's redesigned Peter Eisenman's recent Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe by moving it to the banks of a river and constructing it from glass. In any case, the issue also contains manifestos by design titans like Bruce Mau, John Thackara, and Stefan Sagmeister; architects such as Joshua Prince-Ramus, Thom Mayne, Bernard Khoury, Sam Jacob, Stephen Holl, Vito Acconci, Greg Lynn, Teddy Cruz, and UN Studio; curators Hans Ulrich Obrist and Paola Antonelli; and -ahem- an L.A.-based architecture blogger called BLDGBLOG. As the only blogger included in the fifty manifestos, I'm a little stunned – even half-seriously convinced that some sort of mistake has been made – but hey: it's always fun to be asked for your own architecture manifesto.  [Image: Some page-spreads from Icon #50]. [Image: Some page-spreads from Icon #50].On the other hand, is BLDGBLOG really written by one of "the most influential people in architecture and design"...? Next to Rem Koolhaas, Bruce Mau, Ken Livingstone, and Zaha Hadid? I would suspect not, frankly. I would imagine that there's a little bubble of influence somewhere; but globally? Historically? I wouldn't exactly complain if that were the case – if people really wanted a bit more J.G. Ballard, John McPhee, Jeff VanderMeer, terrestrial prostheses, heliocentric Pantheons, and undiscovered bedrooms in their architectural discourse – but I'm not actually convinced that's true. I think people would rather learn where to buy designer couches. Anyway, long-term readers of BLDGBLOG won't find any surprises in what I have to say: There is architecture lining the streets of New York and Paris, sure – but there is architecture in the novels of Franz Kafka and W.G. Sebald and in The Odyssey. There is architecture on stage at the Old Vic each night, and in the paintings of de Chirico, and in the secret prisons of military superpowers. There is architecture in our dreams, poems, TV shows, ads and videogames – as well as in the toy sets of children. The suburbs are architecture; bonded warehouses are architecture; slums are architecture; NASA’s lunar base plans are architecture – as are the space stations in orbit [above] us." But, still, if you run into a copy of Icon #50, be sure to check it out. And I should also mention that the issue includes a positive review of Postopolis!, written by Bill Millard, who sat through all five sweaty days of the event with us, taking notes and asking questions. More on Postopolis! can be found here and here. (Note: The phrase "nihilistic ravings of insomniac bohemians," used in the title of this post, is an excerpt from Icon editor Justin McGuirk's introduction to the 50 manifestos).

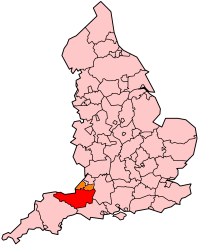

[Images: Cacti at the Huntington Library in Pasadena]. [Images: Cacti at the Huntington Library in Pasadena].My wife and I went out to the Huntington's Desert Garden yesterday. I have to admit to a certain wild amount of enthusiasm for high-end botanical environments like that. Being a fan of Kew Gardens, for instance, or Longwood Gardens, or even small local greenhouses and the like, I have a huge soft-spot for regions of the Earth's surface that have been deliberately cultivated to support rare – or at least highly condition-dependent – plantlife. In the case of Kew and Longwood, you walk through elaborate, mist-filled greenhouses, passing orchids and ferns – but the word greenhouse is actually a form of structural shorthand, saying, in fact, that architecture has been put to use in the evolutionary hybridization of plantlife: flowers, fruits, and other animate forms that would, naturally, have grown elsewhere. By establishing micro-climates, with often extreme variation from building to building, in both temperature and humidity, architecture participates directly in botanical speciation.  [Image: Cacti at the Huntington Library in Pasadena]. [Image: Cacti at the Huntington Library in Pasadena].In any case, these thoughts don't actually apply to the Huntington Desert Garden, which is entirely outdoors – or, at least, the part of it that we visited was entirely outdoors, in the dry heat of a spectacular, arm-sunburning day – but no matter: either way, it's hard to have a bad time walking around in the Huntington's linked network of curved paths past biomorphically avant-garde cacti and spiked trees so surreal they appear literally extraterrestrial. Briefly, all of this reminds me of an incredible fact I read last week in the London Review of Books: Stefan Buczacki, the author of Garden Natural History, has "calculate[d] that private gardens [in England] occupy an area about the size of Somerset, and they play an important part in maintaining the populations of many species."  [Image: Somerset County, England]. [Image: Somerset County, England].That is to say: an area in England the size of Somerset is actually a kind of biological transplant: a deliberately cultivated micro-climate, or genetic testing site, with its own yet to be calculated effects both on native plants and animals and on the British climate. At what point, then, do privately held and cultivated landscapes become naturalized as a region's terrain, or as part of that region's native biosphere? It's a surrogate, or prosthetic, ecosystem – a kind of skin graft – masquerading as the thing that's been replaced. Think of it as the English family garden as replicant. In other words, if English private gardens proliferate to the point where an area not just the size of Somerset County, but of, say, Somerset, Wiltshire, and Gloucestershire combined, then do artificial landscapes become indicative of England itself? Or, to use an absurd analogy, if the band Napalm Death now has no connection to the original band – because all of the original members have left – indeed, as Wikipedia points out, "by the second side of their debut album... they did not contain any original members" – is it possible that, in a thousand years' time, or in five thousand years' time – or even in fifty – that "England" will soon be England in name only, having been slowly replaced, piece by piece – a garden here, a garden there – until the Britannic landscape is entirely manmade and it's become impossible to locate even a trace of native vegetation? A kind of ecological bait-and-switch? You book a trip to England – but you're visiting an island made entirely from private gardens, a vast, unnatural landscape ruled over by a King. In any case, the Huntington Desert Garden is a spectacular place to visit, and as good a place as any in which to think about the local cultivation of non-native landscapes. So if you're ever in Los Angeles, consider stopping by. (Earlier on BLDGBLOG: Kew Brew, or: turning endangered landscapes into beer).

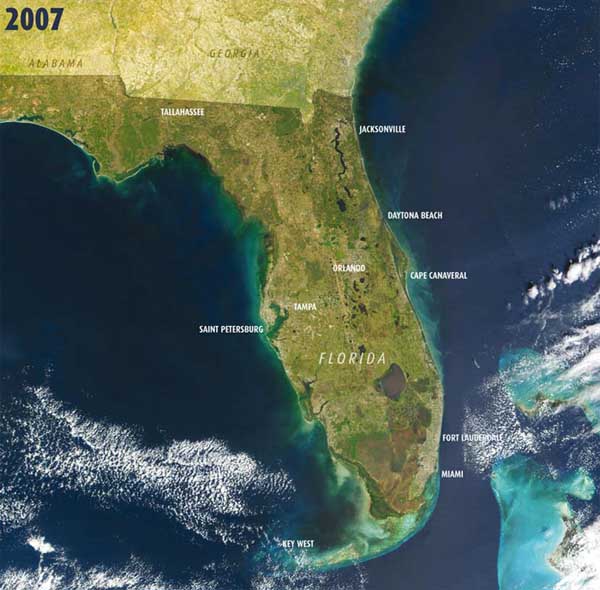

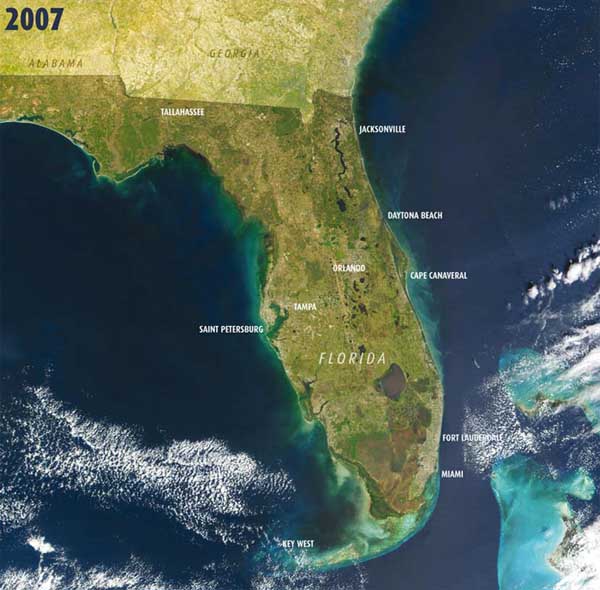

[Image: Florida in 2007; via New Scientist]. [Image: Florida in 2007; via New Scientist].In a subscriber-only article over at New Scientist, NASA climate scientist James Hansen describes what the planet might look like after a "runaway collapse" of the West Antarctic ice sheet. The collapse, or melting, of the sheet, of course, would be caused by increased global temperatures – temperatures altered by the atmospherically unique quantity of carbon dioxide that's now floating around up there. That carbon dioxide has been released by human industrial processes. "There is not a sufficiently widespread appreciation of the implications of putting back into the air a large fraction of the carbon stored in the ground over epochs of geologic time," Hansen writes.  [Image: Florida in 2107; via New Scientist]. [Image: Florida in 2107; via New Scientist].In any case, the article points out that this future sea-level rise will actually increase over time, as the melting of the ice sheet itself accelerates. As an example, let us say that ice sheet melting adds 1 centimetre to sea level for the decade 2005 to 2015, and that this doubles each decade until the West Antarctic ice sheet is largely depleted. This would yield a rise in sea level of more than 5 metres by 2095. That would be more than enough to flood London, as discussed in the previous post – not to mention Shanghai, New York, Mumbai, and so on. From the article: Without mega-engineering projects to protect them, a 5-metre rise would inundate large parts of many cities – including New York, London, Sydney, Vancouver, Mumbai and Tokyo – and leave surrounding areas vulnerable to storm surges. In Florida, Louisiana, the Netherlands, Bangladesh and elsewhere, whole regions and cities may vanish. China's economic powerhouse, Shanghai, has an average elevation of just 4 metres. This is obviously meant as a warning. However, the main problem I have with using maps and scenarios like this to get people worked up about climate change is that these warnings often seem to have the opposite effect. In other words, these things are actually so evocative, and so imaginatively stimulating, that it's hard not to get at least a tiny thrill at the idea that you might get to see these things happen. Nothing against Miami, but all of south Florida under several meters of water? With Cape Canaveral lost under a subtropical lagoon and St. Petersburg an archipelago? The problem, it seems, is that climate change scientists, in describing these unearthly terrestrial reorganizations, are science fictionalizing, so to speak, our everyday existence. The implicit, if inadvertant, message here seems to be: hey, south Floridians, and all you who are bored of the world today, sick of all the parking lots and the 7-11s, tired of watching Cops, tired of applying to colleges you don't really want to go to, tired of credit card debt and bad marriages, don't worry. This will all be underwater soon. It could be called liberation hydrology. Climate change becomes an adventure – the becoming-science-fiction of everyday life.  [Image: Northwestern Europe in 2107; via New Scientist]. [Image: Northwestern Europe in 2107; via New Scientist].It seems no wonder, then, that the more apocalyptic these scenarios get, the more we find the same blasé reaction: oh, you mean Manhattan will be underwater? In 100 years? I think the way to get people truly concerned about climate change – if fear-mongering is, in fact, the correct strategy to use here (after all, if you don't like fear-mongering in the War on Terror, then why should you apply the same tactics to climate change?) – is not by talking about unprecedented and spectacular transformations of the Earth's surface. New archipelagos! Forests in Antarctica! Drowned cities!Instead, it would seem, you have to point out quality of life issues: you might starve to death, for instance, as organized agriculture and food distribution chains are interrupted. Malnourished, your teeth will fall out and your hair will grow thin. You may be living in a refugee camp, with neither privacy nor close friends nor personal safety. The governments of the world may have collapsed, overwhelmed by the logistical burden of displaced populations and by the loss of the world's economic centers, like NY, London, and Shanghai; there will thus be no police; you might be physically assaulted on a regular basis. There will be rats, roaches, and rivers of human sewage – followed closely by disease, infection, infant mortality, and premature death. And you won't just be able to drive away, leaving the catastrophe behind – because the roads will be potholed, without a government to fix them, and your car will probably have been stolen, anyway. Clean water will be a luxury; you'll be drinking radiator water out of abandoned pick-up trucks, rusting on the sides of highways outside St. Louis. In any case, my point is just that the more outlandish and imaginatively evocative your predictions get, describing some new, fantasy geography of rising sea-levels and tropical lagoons – a whole new Earth, coming your way soon – the more people will actually want to see that happen. Of course, the same thing is no doubt true for what I just wrote, above, in describing the apocalypse: after all, there are many people who will actually want to experience that – unpoliced refugee camps included. Still, showing maps of an unrecognizable future world doesn't scare people; it taps into their explorer instinct – new lands, terra incognita. And it gives people some truly awesome scenarios to think about – like scuba-diving through the submerged remains of Cape Canaveral, or rediscovering Amsterdam, a city lost to the silt and seaweed. If this is what people think climate change will bring them, then a whole lot of people are probably looking forward to it.

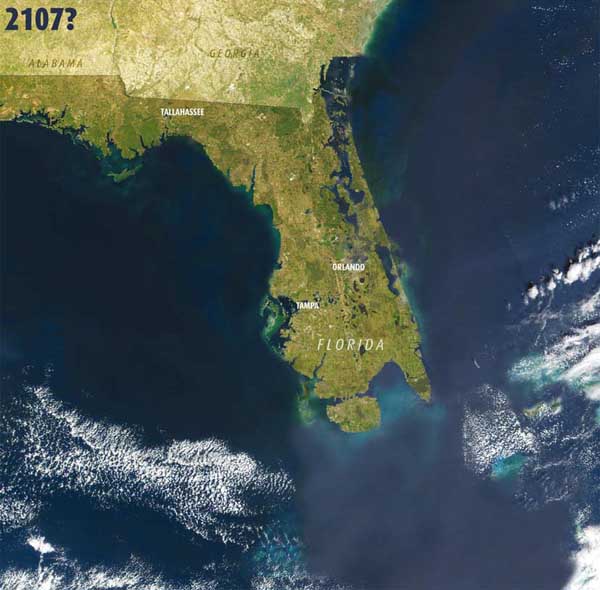

[Image: A thoughtfully signposted British flood; photo by Matt Cardy for Getty Images]. [Image: A thoughtfully signposted British flood; photo by Matt Cardy for Getty Images].I'm totally fascinated by the idea that adventure tourism firms might someday lead wreck-diving tours through the flooded ruins of London: in your expensive re-breathing gear, you'll roll backward off a boat, flashlight in hand... and the coral-specked vaults of St. Paul's are now yours to explore. All the churches of Nicholas Hawksmoor, as seen through a diving mask. Or the Tube, full of moray eels, awaiting the truly brave. Fantastically, that's not so unrealistic an image – because London, after all, is sinking. Using satellite measurement, tide gauges, GPS, and a few other devices called "absolute gravimeters," a new study proves that London is moving downward into the Earth's surface in "a general pattern of subsidence of 1-2mm a year. With waters rising in the region by about 1mm a year, the combined effect is a 2-3mm a year rise in sea level with respect to the land." The investigation confirms geologic studies that show the Earth's crust is still responding to the loss of the heavy ice sheet which covered much of Britain more than 10,000 years ago – with southeast England, including London, slowly sinking. Do some basic math, and that puts London under three meters of water in roughly 1000 years – and London, incredibly, will have passed through the other side of the planet in less than – whoa – To help protect against these encoaching waters, the city contains or is surrounded by a rarely noticed hydrological labyrinth: "300km of tidal defences including embankments, walls, gates and barriers." However, "at some stage, [these will] have to be adapted or moved" – at least until "new types of defences [are] created that make better use of the natural floodplain." I love this stuff. In fact, I'm 100% convinced that if architectural magazines really wanted to discuss what the London of tomorrow will look like, they'd have stopped talking to architects a long time ago – and they'd have flood consultants on the phone. The future of London will be determined by hydrological engineers.  [Image: The Tewkesbury flood of 2007, as seen from the air; photo by Daniel Berehulak for Getty Images]. [Image: The Tewkesbury flood of 2007, as seen from the air; photo by Daniel Berehulak for Getty Images].In any case, London is also jostling up and down on the Earth's surface, everyday, bobbing up and down like a buoy with the tides; these micro-movements need to be taken into account by anyone who hopes to study the effects of so-called post-glacial rebound. London itself will rock by 10mm, twice a day, with loading from ocean tides. The seasons also alternately load and unload the ground, making the Earth's crust "breathe" up and down over a longer period. London, your tides are breathing you. An Albionic lung. But if you want more stuff like that, this older post is rather heavy on British hydro-speculation. Meanwhile, a "lost" village in Wiltshire might offer a glimpse of London's own future to come. From the BBC: A team of divers who set out to solve the mystery of the drowned village of Bowood in Wiltshire has found the remains of buildings under a lake. If that sounded easy, though, consider that "[p]revious attempts to find the village included a dive by Bowood owner Lord Lansdowne, the 9th Marquis of Lansdowne, who donned his scuba gear 20 years ago. His attempt was unsuccessful." So will aquatic archaeologists someday dive into the kelp-choked canyons of what was once Islington High Street, looking for lost malls and cinemas...? This blogger thinks so. Moving on: in an amazing story that was reported – and repeated – all over the place last week, we learned that a thin ridge of chalk once connected SE England to NW France. The image, below, is BLDGBLOG's own highly inaccurate, and grossly out of scale, representation of what that ridge might have looked like.  Calculated to stop the hearts of English people the world over, those maps show us a land-bridge, continentalizing Kent, putting Franco in the Anglo and de-Saxonizing the island from its royal isolation. And I have no idea what that sentence means, either.  [Image: A slightly more accurate map of both the chalk ridge and the glacial lake it held back; via the BBC]. [Image: A slightly more accurate map of both the chalk ridge and the glacial lake it held back; via the BBC].According to New Scientist: "Half a million years ago, Britain was connected to mainland Europe by a broad chalk ridge that spanned what we now call the Dover Strait. But somehow that ridge was destroyed, forever separating England and France." A new theory holds that this ancient chalk ridge was "breached and toppled by a monumental torrent that gushed from an overfilling glacial lake that the ridge had been damming on its northern side." As evidence of its passing, the catastrophic flood left "deep valleys gouged into the channel's bedrock," turning what is now England, Scotland, and Wales into one big happy island. "At its peak," the BBC adds, "it is believed that the megaflood could have lasted several months, discharging an estimated one million cubic metres of water per second." However, New Scientist quietly points out that Alec Smith, of Bedford College, London, once suggested this exact same idea, back in 1985 – and he was ridiculed. Nobody believed him. Sorry, Alec. Finally, it would have been hard to miss all the news about last week's floods across England – so I'll just supply these links and let the pictures do the talking.  [Image: The Tewkesbury flood of 2007, as seen from the air; photo by Daniel Berehulak for Getty Images]. [Image: The Tewkesbury flood of 2007, as seen from the air; photo by Daniel Berehulak for Getty Images].But, of course, England has a deep history of flooding... (Note: The Wiltshire lost village link was discovered via an amazing post at things magazine, a reliable source of great links and information – for anyone out there who doesn't already know it).

Last summer, BLDGBLOG interviewed author Erik Davis about Davis's new book The Visionary State – a book that was originally sent to me on the advice of a woman named Theresa Duncan. Theresa was the author of an often disarmingly sharp blog called The Wit of the Staircase.  [Image: Artist/photographer unknown. From an old post on The Wit of the Staircase]. [Image: Artist/photographer unknown. From an old post on The Wit of the Staircase].When I announced that BLDGBLOG was moving to Los Angeles last September, Theresa and I got in touch, and we began emailing here and there, maybe once a month. Soon, I saw her at the first BLDGBLOG event, back in January; she and her boyfriend, artist Jeremy Blake, tried to meet up with me and my wife at David Maisel's L.A. opening gala (but our timing was off); and then, after she and Jeremy moved back to NYC, to live in the attic of a church in Manhattan's East Village, they stopped by the closing party for Postopolis! She also sent me links here and there, and her emails were incredibly encouraging – in fact, she's one of the people I thanked when announcing the BLDGBLOG Book back in May. So I was stunned, saddened, and horrified to learn, in the context of an otherwise casual email exchange, that Theresa committed suicide two weeks ago. Somehow I missed the news. A few days later, her boyfriend, Jeremy Blake, left behind a note in a pile of clothes on the beach and then "walked into" the Atlantic – and his body has yet to be found. The story's been all over The New York Times, The L.A. Times, Modern Art Notes – basically everywhere – even as author Ron Rosenbaum has been using their deaths, somewhat irresponsibly, to speculate about what he wants to believe was a murder. Of course, Theresa was well-known for her "paranoiac" writings about Scientology, the art world, CIA black ops, secret FBI files, and the like – this post, in particular, has received a huge amount of attention this past week (and it's a crazy thing to read) – but to throw her entire blog away as mere political ravings overlooks the vast majority of the site's actual content: short observations – often limited to single quotations and photographs – with an articulate precision and interpretive confidence other writers would only dream of achieving. She could be writing about supermodels, the occult, music, 9/11, Percy Bysshe Shelley, perfume, Los Angeles, or the films of Quentin Tarantino. Not everyone will agree with the political views espoused in this essay, for instance, but Theresa wrote one of the best and most energetic reviews of Grindhouse I've ever read; and she posted a long interview with Father Frank Morales, an Episcopal priest, in which they talk about everything from Philip K. Dick and Jerry Falwell to the Moonies, Freud, Marx, science fiction, and Disneyland – all by way of a discussion about Jesus Christ. Here's an excerpt: Wit of the Staircase: You know, Philip K. Dick is really interesting on this, too, because he had a conversion experience in California – he famously lived next door to Disneyland – and a woman came to the door. She was wearing a fish sign, a Pisces sign that the early Christians used. And he claims he had this sort of mystical experience that was across dimensions of time. And he actually suddenly felt that time was an illusion. So he said ever after he had the feeling time was essentially created by Satan to prolong and delay the return of Jesus Christ, the Second Coming. So, under all of the supposed progress and all of the change, he says it's just an overlay over the same unchanging reality. It's still like the day that Christ died, and he felt the anticipation of resurrection, the thrill, he says, constantly.

Frank Morales: I totally agree with that.

Wit: So other than the hucksters, the Falwells and the L. Ron Hubbards of the world, there are these startlingly generous and original religious thinkers. P. K. Dick – obviously, he's a little wiggy, but he's an original thinker, and this old narrative was just completely alive for him. And Slavoj Žižek is great on the continuing radicality of Christian love and forgiveness, particularly in his book The Puppet and The Dwarf, which is also thankfully very good on Freud and Marx.

Morales: As a matter of fact, to use that metaphor again, without sounding preachy, reminds me of Buckminster Fuller's comments, why do you think they call the basic element of time "the second"? Because it's not the first.

Wit: Well, because P.K. Dick lived next to Disney World, he talked about the animatronics there – the servo operated puppets and the moving pirates and the fake birds – a place everything was artificial. And he said that that's like the second reality. But he said, someday a real bird was going to sing at Disneyland and uncover the first reality.

Morales: Ah, beautiful. In any case, this is personal news creeping onto an architecture website – but I'm stunned. And I don't mean to imply that we were close friends – we weren't – in fact, we only communicated through email. But sometimes you look away and things just disappear.

There's a great documentary on PBS tonight, called Prison Town, USA. "What happens when a struggling rural community tries to revive its economy by inviting prisons in?" the film asks.  [Image: Prison Town, USA]. [Image: Prison Town, USA].In focusing on the rural "prison town" of Susanville, California, the film presents "a riveting look at one of the most striking phenomena of our times: a prison-building and incarceration boom unprecedented in American history." Indeed, this unprecedented "incarceration boom" hit the point where, "during the 1990s, a prison opened every 15 days." The United States now has the dubious distinction of incarcerating more people per capita than any other country in the world. Yet this astonishing jailing of America has been little noted because many of the prisons have opened in remote areas like Susanville. Prison Town, USA examines one of the country's biggest prison towns, a place where a new correctional economy encompasses not only prisoners, guards and their families, but the whole community. California's corrections industry, in particular – which now receives more state funding than does California's university system – is "hungry for space, new guards and low visibility," and so distant, rarely visited towns like Susanville seem perfect. Meanwhile, in an interview with the filmmakers, we learn a bit more about this "correctional economy": The prison boom came in the wake of traditional industries waning for decades since the 1950s. Ranching, mining and milling got outsourced. Then, when the political climate shifted and prison expansion began, people in the towns welcomed prison officials when they said: "We're going to build a prison, it's going to create jobs, and you'll be able to count the prisoners in your census numbers." But they didn't understand that the repercussions are huge. You get a lot of money that comes in through higher wages that the guards make, but there are Wal-Marts and fast food joints that just flow in after the prison. That's part and parcel of the prison expansion, and local businesses don't get that money, the big, big corporations do, so the money doesn't even stay in Susanville. Further, there is an accompanying correctional geography, similar to what Bryan Finoki and others would call a carceral urbanism.  [Image: Prison Town, USA]. [Image: Prison Town, USA].For instance, the fact that "prisoners are counted by the census in the towns where they're imprisoned rather than the towns they call home" leads to a "huge shift of resources – political, economic, social services, et cetera – from the urban areas where most of the inmates come from to these rural areas." Specifically, as "federal and state money moves from urban areas to rural areas," "census lines are redrawn" and otherwise insignificant little towns like Susanville can gain "a lot of political clout" by inviting this national "prison expansion" in. In any case, I got to see a copy of the film last night, and I'd really recommend seeing it. So, if you're near a television (and in the United States) tonight, give it a shot. Here's the trailer.

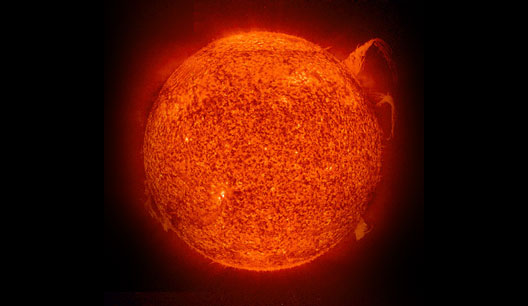

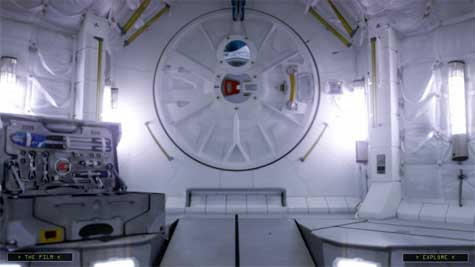

[Image: The cast of Sunshine; courtesy of DNA Films]. [Image: The cast of Sunshine; courtesy of DNA Films].I saw Sunshine the other day, so I thought I'd offer a few thoughts about it here. However, please beware that this post gives away key plot details and spoils the end of the film – so do not read this post if you'd like to avoid such knowledge. In brief, myself and two friends went to see the film together – and we had three totally different reactions. One of us was basically annoyed with it from the very beginning – and a weird plot twist, that I'll soon discuss, about 5/6ths of the way through the movie, just killed it for him; the other more or less liked everything about the film, even accepting said "weird plot twist" for interesting reasons of his own; and I really liked the film, with several reservations, until, yes, the aforementioned weird plot twist – which basically does the whole thing in for me. In fact, I'm still stunned that this one particular detail ever made it into the script. In any case, what the film does – and it does this very successfully, in my opinion – is set up an increasingly melancholy sense of psychological isolation as an international crew of scientists, aboard a ship called the Icarus 2, flies toward the Sun. The Sun, we learn, is dying – and so it needs to be restarted with a "stellar bomb" the size of Manhattan. In fact, we learn, the bomb is so big that it contains literally all of the Earth's fissile material. Once detonated, it will form "a star within a star" – a surrogate astronomy, or Sun-replacement surgery, that will save everyone back on Earth from the perpetual winter in which they've been trapped. Whether or not this would actually work, from the standpoint of an astral physicist, is beside the point; you're asked to accept this, as the basic plot of the film, and, as far as that goes, I accepted it. Meanwhile, the visual and conceptual beauty of certain scenes – they witness a transit of Mercury, for instance – is extraordinary. Further, the possibility that they may not make it back to Earth, though still unlikely at the film's beginning, adds a distinct aura of extinction and exclusivity to everything they see. No one will ever see these things again.    [Images: Screen-grabs from the Sunshine website; courtesy of DNA Films]. [Images: Screen-grabs from the Sunshine website; courtesy of DNA Films].However, as the ship approaches its solar rendezvous, a kind of elemental, alien hostility begins to emerge – not from within the crew members, but from within the Sun itself. Far from being a beneficent source of light in the sky, generously tanning the bodies of we Earthlings below, the Sun is revealed as a monstrous and abiological source of mutative radiation, inhumanly immense, so bright you can't see it, disintegrating nearly everything that comes near. One of the crewmembers – the resident psychiatrist – becomes addicted to the star: he can't stop burning himself with more and more quantities of sunlight, asking the ship's central computer to increase the unfiltered percentage that is allowed through the observation deck window. With his skin peeling and his mouth hanging open, he nearly disappears into a void made entirely of light – golden, enveloping him on all sides – yet we hear, incredibly, that he's only receiving 3.1% of the Sun's natural capacity. 4%, we're told, would destroy the psychiatrist outright – let alone 50% or 90%, or the Sun itself, unfiltered. In fact, for me, the film very brilliantly illustrates the paradox that something can be so powerful that the ability to experience it is simply beyond the limits of human life – outside of human experience altogether.  [Image: The sun]. [Image: The sun].Anyway, if the first 4/5ths or even 5/6ths of the film are about this painfully beautiful, almost evaporative, encounter with an alien and threateningly vast – yet so ironically necessary to life on Earth – stellar object, then the "weird plot twist" that I mentioned above feels as if the ending to another film had been accidentally stitched on in the editing room. In brief: Sunshine suddenly turns into The Texas Chainsaw Massacre.  [Image: The ship from Sunshine; courtesy of DNA Films]. [Image: The ship from Sunshine; courtesy of DNA Films].It's as if the film shies away from its own material, unable, or unwilling, to contemplate what might happen if people, aware of their own impending deaths, fly straight into the Sun – an origin point devoid of recognizability – and so they throw a serial killer in, almost literally out of nowhere. The film could have been stunning: the crew is pared down, one by one, by accidents or oxygen shortages, and even a suicide, until only three or four of them are left. They know that they will never return; they know that they will die unprecedented deaths, obliterated by Apollo, by God, by the Sun – by whatever you want to call it; and they are terrified by that rapturous undoing, unable to narrate their final experience for anyone back home, truly cut off yet almost psychedelically alive in this moment of solar contact... But that's not how the film ends.  [Image: The flight deck from Sunshine, in a screen-grab from the film's website; courtesy of DNA Films]. [Image: The flight deck from Sunshine, in a screen-grab from the film's website; courtesy of DNA Films].Midway through Sunshine, a distress beacon is heard. It's from the mission before their mission – the one that failed. That ship – called Icarus 1 – disappeared nearly seven years ago, somewhere in the irradiated gulf between Mercury and the Sun. In a decision that, I'll concede, is necessary for certain things to come but is still so ridiculous as to make viewers question the competence of the entire crew – the last great hope of humanity! – they decide to deviate their mission in order to find the lost ship. Lo! They find the lost ship. Lo! They know exactly how to dock with it, despite – for obvious reasons – never having practiced anything of the sort. Lo! Unbeknownst to them, the captain of the Icarus 1 is still alive – and he hides out on the Icarus 2, escaping notice. Like a comic book superhero, he's survived seven years alone on a disabled spaceship floating between Mercury and the Sun – without being pulled in by that star's gravity. As if serving simply to make the film's existential themes explicit, he has also pre-recorded an angry and completely unhinged theological rant about God's Will and the absurdity of Man trying to restart the Sun. Even more unbelievably, it turns out that this guy isn't malnourished, semi-skeletal, or even psychologically catatonic: no, after seven years alone, eating hydroponic carrots in space, he's become a superstrong, sunburnt Hercules, capable of lifting two crewmembers at a time with one arm whilst chasing everyone else down and murdering them with a mechanized surgical scalpel.   [Images: Two views of the airlock from Sunshine, in screen-grabs from the film's website; courtesy of DNA Films].Where did this come from? [Images: Two views of the airlock from Sunshine, in screen-grabs from the film's website; courtesy of DNA Films].Where did this come from? And why? At the risk of wildly exaggerrating the philosophical depth of the first 5/6ths of the film, this seems roughly akin to throwing in a serial killer for the last three chapters of Thus Spoke Zarathustra – Nietzsche is chased through the claustrophobic rooms of his mountain home – or adding the Son of Sam to the grand finale of the Tao Te Ching. In any case, can you really be so scared of your own premise – the unwitnessed and lonely deaths of an oxygen-starved crew as they fly into the Sun, toting a "stellar bomb" the size of Manhattan (talk about mythological plotlines!) – that you have to add Freddy Krueger? Even worse, the film had already established by then that no one would survive. The film had already established that the Sun was a source of great attractive power, far beyond the mere pull of gravity, and that it was possible to become hypnotized by, even addicted, to the very thing that would later annihilate you – and that this death would be more horrible than human pain can describe, yet something of such exquisite agony, and so spectacular, something uniquely sublime in the history of human experience, that you would actually want to feel it. You would fall toward roiling continents of hydrogen and light, and you would be utterly consumed by your destination. It would have been the science fiction film of the decade! An instant classic. Instead, just when everyone has settled in for the ending, waiting for that golden burn, our mutant Hercules of unlimited arm strength appears, creeping up behind people in the dark and knifing them in the spine. How could you cheat the audience and the characters out of the philosophical glory of solar absorption? Sunshine would practically have been a religious text, a near classic work of speculative philosophy exploring what it means not just to die but to be completely obliterated, atomically consumed in chemical radiance by the same two-faced point of origin that makes life on Earth possible in the first place. Imagine if the Chandogya Upanishad ended not with the nature of time, space, life, and astronomy – but with an ax murderer. Or Siddhartha: the Buddha is inexplicably hunted by an escaped convict with a chainsaw... (That sounds kind of fun, actually).Does this mean that I am comparing the film Sunshine to the Chandogya Upanisad? Well... I suppose I am, out of over-enthusiasm – but I am also saying that Sunshine wildly misses that mark. Instead of going for cinematic magnificence, and it was well on its way to arriving there, it takes a disastrous step back – and reveals itself as a cheap, quasi-1990s space-horror misfire. Was the knife-wielding lunatic evidence of tampering by the studio? In other words, did the film's producers demand more of a predictable impact? Or did Alex Garland write that guy into the original script? If so, why? Were the filmmakers pleased with the final result? Were they so unhappy with the idea of flying their own crew into the Sun that they added an interstellar He-Man, sunburnt and stronger than Arnold Schwarzeneggar? Or was the knife-wielding lunatic a way to screen the filmmakers themselves from the imaginative power of their own subject matter? Was there something about the premise itself – total absorption by a featureless, golden void – that forced them to retreat, and to insert something that they and, they hoped, the audience could recognize?  [Image: Cillian Murphy runs from a knife-wielding, sunburnt lunatic in Sunshine, a screen-grab from the film's website; courtesy of DNA Films]. [Image: Cillian Murphy runs from a knife-wielding, sunburnt lunatic in Sunshine, a screen-grab from the film's website; courtesy of DNA Films].Like I say, if the film hadn't already been on its way to the final credits, with no need for such a plot twist, I could perhaps have accepted the chromosomally damaged avenger. If it had been the ship's resident psychiatrist, for instance, psychotically consumed by the Apollonian power of astral radiance, at least it would have been neat and tidy – if still clichéd. But since we were already on our way into the Sun, already past the point of even thinking that the crew might return home, already accepting the fact that everyone in the film would die heroic, astronomically unprecedented deaths, why did we need the murderous accelerant of a Sun-addled stowaway? That does nothing more than rob the film of its poetic grandeur – so that the filmmakers could safely turn their back on philosophy and create Leviathan in zero-G. (Thanks to Christopher and Michael for seeing the film with me – and for listening to me rant about all of the above for nearly two hours. Meanwhile, if you completely disagree with this review, please jump in and convince me otherwise. Earlier on BLDGBLOG: The Oxygen Garden).

[Image: A wonderfully disorienting image, called Proper Project Orientation, by Vancouver-based photographer Bill MacEwen – an image so spatially evocative, with its labyrinth of scaffolding, ladders, surfaces, and stairways – a horizontal universe of painterly self-connectedness – that I'd rather not reveal what the photo actually is. Is it a billboard, re-designed by Lebbeus Woods? Or a painting? Perhaps it's a drive-in cinema after an atom bomb has hit... It's better just to stare and enjoy – while viewing the original photo here. (Thanks, Bill!]. [Image: A wonderfully disorienting image, called Proper Project Orientation, by Vancouver-based photographer Bill MacEwen – an image so spatially evocative, with its labyrinth of scaffolding, ladders, surfaces, and stairways – a horizontal universe of painterly self-connectedness – that I'd rather not reveal what the photo actually is. Is it a billboard, re-designed by Lebbeus Woods? Or a painting? Perhaps it's a drive-in cinema after an atom bomb has hit... It's better just to stare and enjoy – while viewing the original photo here. (Thanks, Bill!].

[Image: Little Earth by London Fieldworks]. [Image: Little Earth by London Fieldworks].Speaking of surrogate earths, the science-minded arts group London Fieldworks has a project, from 2004, called Little Earth. Little Earth was a "four channel synchronised video installation with surround sound," featuring scenes "shot on Haldde Mountain in the Norwegian Arctic, Ben Nevis in Scotland, and on the island of Svalbard, with computer animations of the Earth’s magnetosphere modeled by the Leicester Radio & Space Plasma Physics Group."  [Image: Another glimpse of Little Earth by London Fieldworks]. [Image: Another glimpse of Little Earth by London Fieldworks].The Independent refers to these latter projections as being "an animated sequence of the Earth enmeshed within its magnetic field lines, which trail off into the solar system." Here are some video stills of the project.     [Images: Film stills from Little Earth by London Fieldworks]. [Images: Film stills from Little Earth by London Fieldworks].Meanwhile, London Fieldworks also produced a short publication about the project; the book includes essays on art, meteorology, and physics. But I was interested to see that the project is at least partly about Norwegian scientist Kristian Birkeland. From the project's website: The Little Earth project identifies two physicists, C.T.R. Wilson and Kristian Birkeland, as significant contributors to 'big science'. Both researchers were stationed at mountaintop observatories studying natural phenomena at the end of the 19th-century. They relied on naked-eye observation and simple instruments in extreme environments and were perhaps the last of the natural philosophers. Associated with the mountaintop experiences of Wilson and Birkeland are two celebrated machines: Wilson’s famous ‘cloud chamber’ and Birkeland’s lesser-known ‘terrella’. The instruments promoted understanding of phenomena at the micro and macro scale – signaling new frontiers for exploration. Among many other reasons, this caught my eye because Birkeland and his "terrella" – which London Fieldworks describe as an artificial "plasma universe" – were the subject of one of the very first BLDGBLOG posts... a post which, in an almost freakish coincidence, I was re-reading just this morning, several hours before I discovered Little Earth (via we make money not art). It's an old post, so it's strangely formatted and a little over-casual, but it's also one of my favorites – so check it out if you get the chance. And if London Fieldworks sounds like an interesting group, you'll be pleased to know that there are several other cool projects described on their website. (Note: Little Earth spotted over at we make money not art).

|

|

The novels of Patrick McGrath are often described as Gothic. They unfold across foggy landscapes and rolling moors, on marshes dotted with isolated houses and dead trees. There is a lot of rain.

The novels of Patrick McGrath are often described as Gothic. They unfold across foggy landscapes and rolling moors, on marshes dotted with isolated houses and dead trees. There is a lot of rain.  A question often asked on this website is: what do novelists, artists, and filmmakers want from landscape and the built environment? More specifically, how can architecture assist a writer as he or she constructs a novel's storyline? Are certain types of buildings more conducive to one kind of plot than to another?

A question often asked on this website is: what do novelists, artists, and filmmakers want from landscape and the built environment? More specifically, how can architecture assist a writer as he or she constructs a novel's storyline? Are certain types of buildings more conducive to one kind of plot than to another?  [Image: Novelist Patrick McGrath].

[Image: Novelist Patrick McGrath].

[Images: The Abbey in the Oakwood, 1809-10, and Cloister Cemetery in the Snow, 1817-19, by Caspar David Friedrich].

[Images: The Abbey in the Oakwood, 1809-10, and Cloister Cemetery in the Snow, 1817-19, by Caspar David Friedrich]. BLDGBLOG: I’m curious if there are any real buildings that you have in mind when you’re describing places like Drogo Hall or Crook Manor. Put another way, could someone ever do a kind of Patrick McGrathian architectural tour, or heritage walk, visiting sites that have inspired your fiction? Where would that tour take them?

BLDGBLOG: I’m curious if there are any real buildings that you have in mind when you’re describing places like Drogo Hall or Crook Manor. Put another way, could someone ever do a kind of Patrick McGrathian architectural tour, or heritage walk, visiting sites that have inspired your fiction? Where would that tour take them? [Images: Castle Drogo].

[Images: Castle Drogo]. [Image: The Hudson River State Hospital, beautifully photographed by Kirkbridebuildings.com. The rest of that site – especially the other hospitals – is well worth checking out].

[Image: The Hudson River State Hospital, beautifully photographed by Kirkbridebuildings.com. The rest of that site – especially the other hospitals – is well worth checking out]. BLDGBLOG: I'm also curious about weather and climate. For instance, a wet climate – with thunderstorms, humidity, and damp – seems to play a major, arguably indispensable, role in the Gothic imagination. Your own novels illustrate this point quite well: from rain-soaked country homes to the Lambeth marshes, from coastal fishing towns to Central American swamps. But can aridity ever be Gothic? In other words, if the constant presence of moisture contributes to a malarial atmosphere of decay, mold, infestation, and disease, might there be a whole other world of psychological implications in a climate where things don't decay – where there is no mold, where bodies turn to leather and everything can be preserved? Is indefinite preservation perhaps a Gothic horror of its own?

BLDGBLOG: I'm also curious about weather and climate. For instance, a wet climate – with thunderstorms, humidity, and damp – seems to play a major, arguably indispensable, role in the Gothic imagination. Your own novels illustrate this point quite well: from rain-soaked country homes to the Lambeth marshes, from coastal fishing towns to Central American swamps. But can aridity ever be Gothic? In other words, if the constant presence of moisture contributes to a malarial atmosphere of decay, mold, infestation, and disease, might there be a whole other world of psychological implications in a climate where things don't decay – where there is no mold, where bodies turn to leather and everything can be preserved? Is indefinite preservation perhaps a Gothic horror of its own? [Image: The Sea of Ice, 1824, by Caspar David Friedrich].

[Image: The Sea of Ice, 1824, by Caspar David Friedrich]. [Image: Monk by the Sea, 1809, by Caspar David Friedrich].

[Image: Monk by the Sea, 1809, by Caspar David Friedrich].

[Image: The cover of

[Image: The cover of  [Image: Some page-spreads from

[Image: Some page-spreads from  [Images: Cacti at the Huntington Library in Pasadena].

[Images: Cacti at the Huntington Library in Pasadena]. [Image: Cacti at the Huntington Library in Pasadena].

[Image: Cacti at the Huntington Library in Pasadena]. [Image:

[Image:  [Image: Florida in 2007; via

[Image: Florida in 2007; via  [Image: Florida in 2107; via

[Image: Florida in 2107; via  [Image: Northwestern Europe in 2107; via

[Image: Northwestern Europe in 2107; via  [Image: A thoughtfully signposted British flood; photo by Matt Cardy for Getty Images].

[Image: A thoughtfully signposted British flood; photo by Matt Cardy for Getty Images]. [Image: The Tewkesbury flood of 2007, as seen from the air; photo by Daniel Berehulak for Getty Images].

[Image: The Tewkesbury flood of 2007, as seen from the air; photo by Daniel Berehulak for Getty Images]. Calculated to stop the hearts of English people the world over, those maps show us a land-bridge, continentalizing Kent, putting Franco in the Anglo and de-Saxonizing the island from its royal isolation. And I have no idea what that sentence means, either.

Calculated to stop the hearts of English people the world over, those maps show us a land-bridge, continentalizing Kent, putting Franco in the Anglo and de-Saxonizing the island from its royal isolation. And I have no idea what that sentence means, either.  [Image: A slightly more accurate map of both the chalk ridge and the glacial lake it held back; via the

[Image: A slightly more accurate map of both the chalk ridge and the glacial lake it held back; via the  [Image: The Tewkesbury flood of 2007, as seen from the air; photo by Daniel Berehulak for Getty Images].

[Image: The Tewkesbury flood of 2007, as seen from the air; photo by Daniel Berehulak for Getty Images]. [Image: Artist/photographer unknown. From an old post on

[Image: Artist/photographer unknown. From an old post on  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: The cast of

[Image: The cast of

[Images: Screen-grabs from the

[Images: Screen-grabs from the  [Image: The sun].

[Image: The sun]. [Image: The ship from

[Image: The ship from  [Image: The flight deck from

[Image: The flight deck from

[Images: Two views of the airlock from

[Images: Two views of the airlock from  [Image: Cillian Murphy runs from a knife-wielding, sunburnt lunatic in

[Image: Cillian Murphy runs from a knife-wielding, sunburnt lunatic in  [Image: A wonderfully disorienting image, called Proper Project Orientation, by Vancouver-based photographer

[Image: A wonderfully disorienting image, called Proper Project Orientation, by Vancouver-based photographer  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: Another glimpse of

[Image: Another glimpse of

[Images: Film stills from

[Images: Film stills from