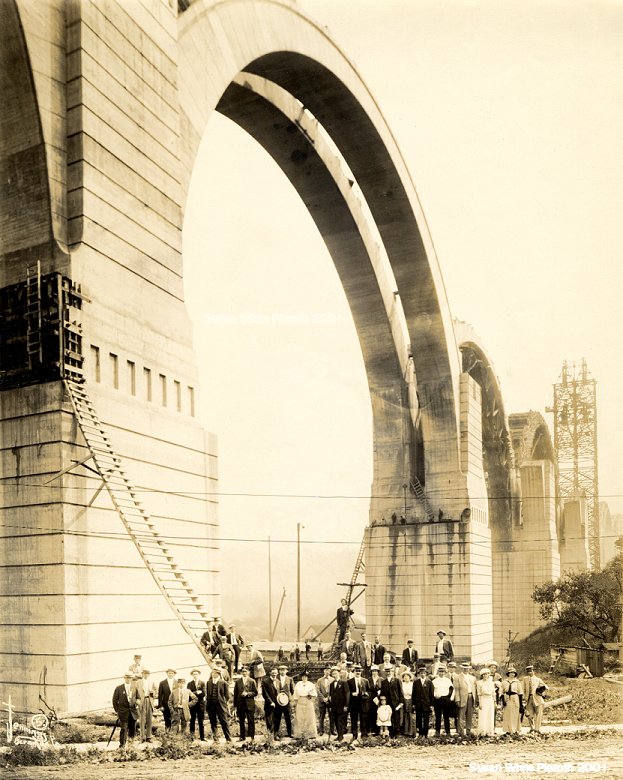

Inside these spans are circles

[Image: The construction of the Nicholson Viaduct; spotted a few days ago at Coudal. While you're at it, take a good, long look through Coudal's voluminous architecture archives].

[Image: The construction of the Nicholson Viaduct; spotted a few days ago at Coudal. While you're at it, take a good, long look through Coudal's voluminous architecture archives].

Inside these spans are circles [Image: The construction of the Nicholson Viaduct; spotted a few days ago at Coudal. While you're at it, take a good, long look through Coudal's voluminous architecture archives]. [Image: The construction of the Nicholson Viaduct; spotted a few days ago at Coudal. While you're at it, take a good, long look through Coudal's voluminous architecture archives].

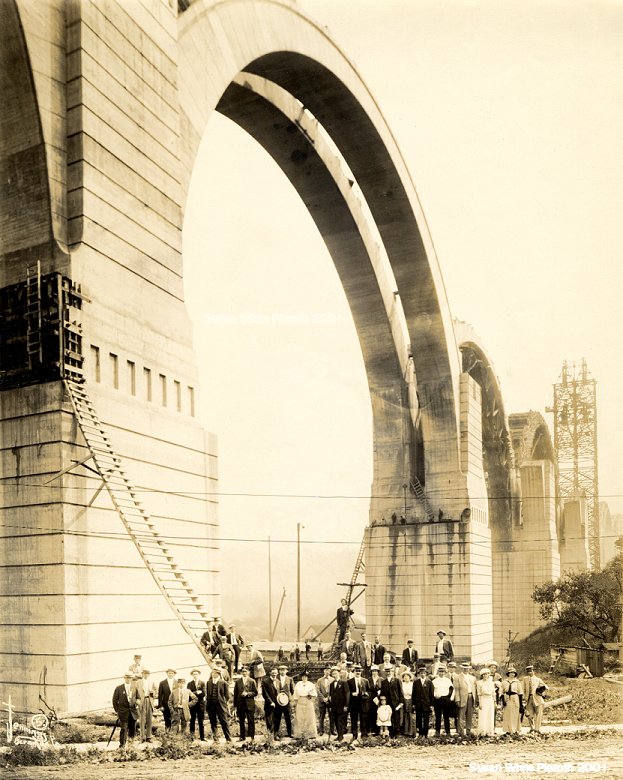

The Oxygen Garden [Image: The Oxygen Garden, from Sunshine; courtesy of DNA Films]. [Image: The Oxygen Garden, from Sunshine; courtesy of DNA Films].The sci-fi film Sunshine – which finally opens in the United States tomorrow – includes a set called the Oxygen Garden.  [Image: The Oxygen Garden, from Sunshine; courtesy of DNA Films]. [Image: The Oxygen Garden, from Sunshine; courtesy of DNA Films].As the film's official website explains: "Oxygen production is vital for manned long-term space flight." Accordingly, "a long-term mission should have a natural, unmechanical way of replenishing its oxygen supplies." Making a few visual references to NASA's early experiments with "space gardens" – and to other artificial landscapes, such as Biosphere 2 – the film's artistic team thus wired together a network of plants, aeration devices, cylindrical grow chambers, and hydroponic vats.  [Image: The Oxygen Garden, from Sunshine; courtesy of DNA Films]. [Image: The Oxygen Garden, from Sunshine; courtesy of DNA Films].The Garden is "one of the most interesting sets" in the film, the website claims, "as the cold, clean 'spaceshipness' is juxtaposed with the wild, dirty nature – this is the only set where there is anything 'green'. All of the plants you see on the set are real, there's not one plastic fern in there at all. When you walk in you are immediately struck by how the set smells. It smells alive."  [Image: A close-up of the Oxygen Garden, from Sunshine; courtesy of DNA Films]. [Image: A close-up of the Oxygen Garden, from Sunshine; courtesy of DNA Films].I have to admit to a certain fascination with surrogate earths: those portable versions of our planet, and its climate, that pop up everywhere from hydroponic gardens, terrariums, and floating greenhouses to complex plans for manned missions to the moon. If only for the purpose of growing vegetables, how can we use technology – fertilizers, UV lights – to reproduce terrestrial conditions elsewhere, in miniature? Under rigorous interpretations of, say, The Bible or The Koran, would this be considered a sin?  [Image: A glimpse inside the Oxygen Garden, from Sunshine; courtesy of DNA Films]. [Image: A glimpse inside the Oxygen Garden, from Sunshine; courtesy of DNA Films].And, finally, what does it mean that the earth itself can enter into a chain of substitutions – a whole economy of counterfeits and stand-ins, referring, through simulation, to a lost original – only to produce something so unearthly as a result? Sponsored Living

Last month I received a press release announcing that Park Fifth, a new condo development here in Los Angeles, has started to offer 5-year memberships in the local Museum of Contemporary Art to anyone who buys a home in the high-rise.

These memberships come as part of an elite residential package, complete with "generously sized balconies or terraces," a few "entertaining areas" scattered throughout the building, and even some "rooftop pools" – all in what will soon be "the tallest residential building west of Chicago." In other words, a little art will come with your luxury.  From the press release: From the press release:

[Image: A screen-grab from the Park Fifth website]. [Image: A screen-grab from the Park Fifth website].The reason I'm posting this, though, is not to make fun of the condo project, but because I love the idea of applying fringe benefits to residential real estate. Anything to make people sign on the dotted line. Your $800,000 condo comes with... a free subscription to The New Yorker. Or maybe a pre-assembled IKEA bookcase full of Penguin Classics. You get a luxury condo and cultural literacy. Dating has never been easier. After all, such benefits wouldn't even cost a developer that much to include. A 5-year Household Membership at MOCA only costs $500 – but folding that into your new $1 million condo purchase has psychological impact: you may have spent that money on something else, for instance, and, this way, you can feel unthreateningly forced into a socially useful lifestyle change. For instance, you could buy a new home in the suburbs... and get 250 Vintage contemporary fiction paperback books thrown in as a signing bonus. Within two years you'll know everything there is to know about American fiction at the turn of the 21st century. Your house could even come with a Borders Rewards card. Hell, you could get a free two-year membership in the Microbrewed Beer of the Month club. Or everyone on your street in the desert outside Phoenix gets a free Smart Car. Residential brand synergies go into hyperdrive. It'd be like those celebrity goodie bags that people like Leonardo DiCaprio and Tyra Banks apparently get on Oscar night – only it'd be for homeowners. In other words, the developers of your building have partnered with the local small business bureau, so that the 2 bed/1 bath home you and your spouse just bought comes complete with 2 free tickets, every week, to the local cinema – as well as 10% off at the nearby Italian restaurant and a free double espresso on your birthday from the Starbucks in the ground floor lobby. Or season tickets to the Eagles. It's the couponing of the residential experience. Toll Brothers signs a marketing contract with Playboy (NSFW), and so that new bungalow you just bought in the Chartresian labyrinth of cul-de-sacs outside Tuscaloosa comes complete with every single issue of Playboy magazine. Houses sell out within days and the neighborhood divorce rate skyrockets.  [Image: Another screen-grab from the Park Fifth website]. [Image: Another screen-grab from the Park Fifth website].Or Richard Branson goes into home development: Virgin Homes. Virgin Condos. Thus, you buy a Virgin Flat and you get two free round-trip tickets, every year for five years, on Virgin Airlines. Anywhere in the world. It's the future of sponsored living. Corporate residentialism. Having said all this, I have to admit – or perhaps it's obvious – that I think offering 5-year memberships at MOCA to all future tenants in the Park Fifth is actually a brilliant marketing move. In fact, at the risk of sounding more enthusiastic than I really am about the commercial possibilities inherent in domestic property ownership, I think fringe benefits of this kind are undoubtedly the future of successful real estate marketing – and that more and more corporate partnerships, between property developers, magazines, airlines, hoteliers, restaurants, book publishers (a free copy of the BLDGBLOG Book for every KB Home customer!), film production companies, beauty products firms, grocery supply chains, health clubs, etc., will wildly proliferate over the next decade. Whether you want them to or not. Buy your house now – and get a complete line of L'Oreal for Men delivered to your door every three months. And a complimentary ticket to Disneyworld. To delete this building, press 3 A few weeks ago, I posted about the "typical dream" of a New Yorker, in which said New Yorker one night discovers a whole extra room hidden away somewhere in an otherwise cramped Manhattan apartment – opening up a disguised door, in the back of the closet... and finding a fully furnished 20'x20' master suite. With a bearskin rug. Or a new bathroom, with gold-plated taps and a trouser press. Or an entire backyard, full of gas grills, hidden behind the living room wall. A few weeks ago, I posted about the "typical dream" of a New Yorker, in which said New Yorker one night discovers a whole extra room hidden away somewhere in an otherwise cramped Manhattan apartment – opening up a disguised door, in the back of the closet... and finding a fully furnished 20'x20' master suite. With a bearskin rug. Or a new bathroom, with gold-plated taps and a trouser press. Or an entire backyard, full of gas grills, hidden behind the living room wall. The ecstasy of having more space in Manhattan. I then suggested that someone should go around New York interviewing people who have had this dream – or asking people who have never had this dream to ad lib, describing what sorts of extra rooms and spaces they would most like to find, tucked away behind the limited square-footage of walls and apartment living. You'd then edit all the responses up into a radio show – and broadcast it live at rush hour, without explanation. The city goes wild. Manhattan is full of extra rooms! people scream. There are secret hallways everywhere! People start knocking on walls and rifling through closets, desperately searching for a place of their own. Maybe an undiscovered planetarium in the basement crawlspace. In any case: we're now doing it. We're making the radio show.  We, in this case, is BLDGBLOG and DJ /rupture (who spoke at Postopolis! last month); we'll be putting your extra room fantasies on the air... We, in this case, is BLDGBLOG and DJ /rupture (who spoke at Postopolis! last month); we'll be putting your extra room fantasies on the air... Specifically, /rup's got a weekly radio show on WFMU – 91.1 FM in New York City – and, to collect your dreams, we've signed up for a free, joint voicemail account. It's voicemail as public recording booth. So what's your extra room fantasy? You don't have to live in New York to answer. If you woke up in the middle of the night and found a door... where would you want it to go? Call +1 (206) 337-1474 and let us know. If we like your story, we'll put you – anonymous, woven into a background of music, without explanation – live on the air in New York City, then podcasted around the world and available via MP3.  Meanwhile, there are ten thousand other potential uses for a voicemail account and a weekly radio show. Meanwhile, there are ten thousand other potential uses for a voicemail account and a weekly radio show.Over the next few weeks and months, then, DJ /rupture and I will be switching things up: asking new questions and looking for new material. For instance, there'll be a field-recordings-by-phone project – where someone standing on the Oregon coast can call +1 (206) 337-1474 and record two minutes' worth of coastal ambiance, which will later be played live on the radio – and a sound-of-your-favorite-bus-stop-as-recorded-by-a-cell-phone project, and a sound-of-your-empty-office-elevator project, and any number of other possibilities. The sound of migrating geese, recorded by cell phone. The sounds of 5th Avenue, recorded using every public phone booth on that street – a kind of sonic history of public space. Maybe even the sounds of famous architectural structures: you're standing inside an empty room in the Empire State Building – so you give us a call: +1 (206) 337-1474. The volumetric reverb of the Taj Mahal. Summer rain pattering against the windows of the Gherkin. Or you're standing on a terrace outside L.A.'s Griffith Observatory, recording the desert wind on an iPhone. It's the voicemail account as musical instrument. Field recordings by phone. How to listen to a landscape. Podcasting space. The unexpected future of audio surveillance.   [Image: DJ /rupture, live in France; DJ /rupture – aka Jace Clayton – speaking at Postopolis! (photo by Nicola Twilley)]. [Image: DJ /rupture, live in France; DJ /rupture – aka Jace Clayton – speaking at Postopolis! (photo by Nicola Twilley)].So stay tuned to WFMU, 91.1 FM in New York City, on Wednesday nights, to hear the results of the voicemail project – the first voicemail fantasies should appear within two weeks – mixed in with some kickin' rekkids by the one and only DJ /rupture. (For a little more about the idea behind this project, see The undiscovered bedrooms of Manhattan). Cinematically mobile in the curved underworld of greater London

It's interesting: videos like these – made by Tube drivers in the tunnels under London as they route trains through the stations of the city – became controversial last week... but not for the reason I would have expected.

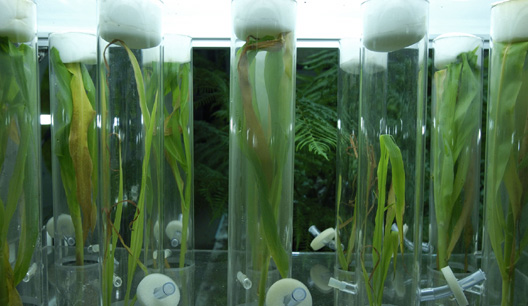

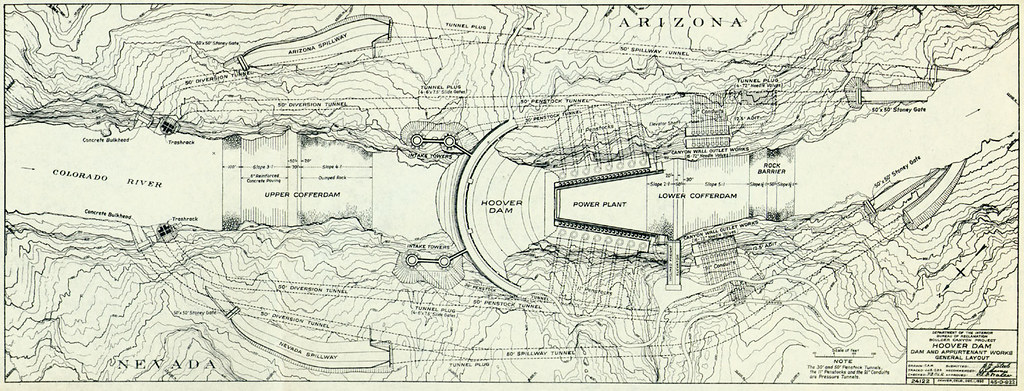

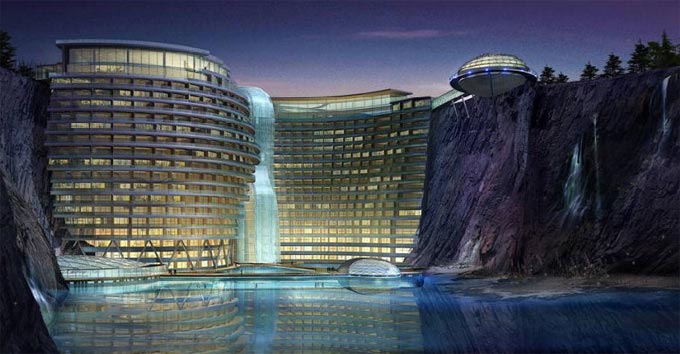

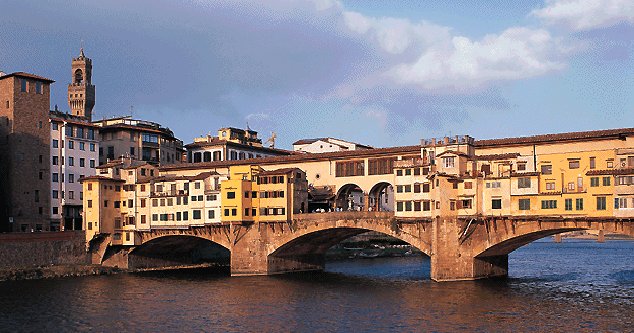

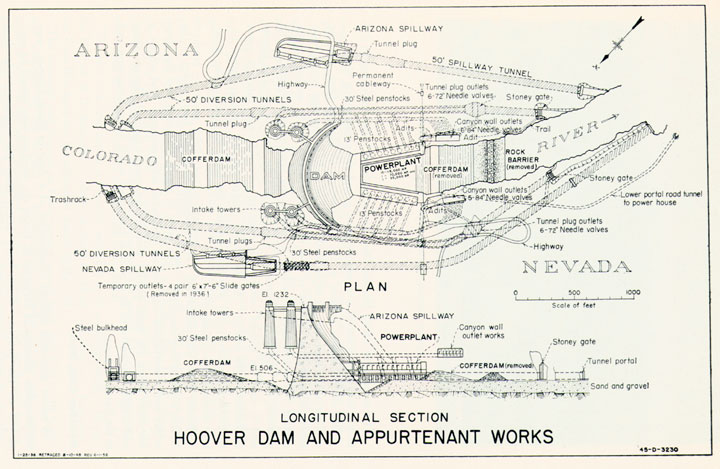

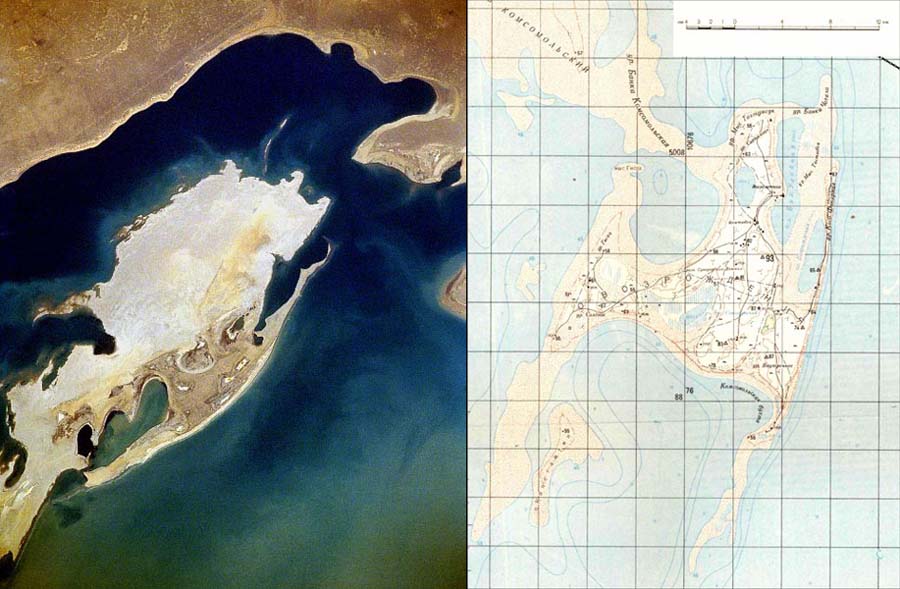

In other words, wannabe terrorists would simply study these and other such videos in order to find points of vulnerability in London's infrastructure: soft spots, weaknesses, CCTV-free zones. But no: apparently the real worry is that the drivers aren't paying attention. As one commuter explained to the BBC: "I'll wait for the next [train] because I feel the driver isn't focused and not doing what he should be doing." After all, instead of paying attention to sudden and inexplicable deviations in the tracks ahead, the driver's too busy constructing a new subterranean Hollywood-on-Thames, cinematically mobile in the curved underworld of greater London. (BBC story – and YouTube links – spotted on Metafilter. Earlier on BLDGBLOG: London Topological). Wirebus [Image: The Wirebus Concept by Mike Doscher. "What if you had a city... where the most common way to get around were cablecars?" Doscher asks. "Can you make a cablecar look cool?" Spotted at Core77]. [Image: The Wirebus Concept by Mike Doscher. "What if you had a city... where the most common way to get around were cablecars?" Doscher asks. "Can you make a cablecar look cool?" Spotted at Core77].(Earlier on BLDGBLOG: Gondolas of New York). We'd all be living in dams [Image: A "contour map" of Hoover Dam; view bigger]. [Image: A "contour map" of Hoover Dam; view bigger].I've found myself in an ongoing thought experiment for the last few months, trying to imagine what it would look like if theoretically non-domestic architectural styles were used to build the houses, or cities, of the future. There are some obvious examples – designing houses like football stadiums, Gothic cathedrals, military bunkers, or nuclear missile silos – or even like Taco Bells, for that matter, or air traffic control towers – but there are also some less obvious, and far more interesting, possibilities out there. Dams, for instance. Why not build your house like a gigantic gravity dam? It wouldn't have to hold back water – so there'd be no flooding to worry about – and you'd have big windows on either side. You'd span canyons and have an incredible roof deck. In fact, when I first saw the image, below, posted on The Cool Hunter back in December, I nearly passed out.  [Image: A development in Songjiang, China, via The Cool Hunter]. [Image: A development in Songjiang, China, via The Cool Hunter].Alas, it's not a dam at all, but the inner wall of a quarry (I still like it). In any case, instead of building habitable bridges, like the Ponte Vecchio in Florence –   [Images: The Ponte Vecchio in Florence]. [Images: The Ponte Vecchio in Florence].– or the Old London Bridge –   [Images: An image of "new houses" built across the river, followed by a spectacular image, by Peter Jackson, of the Old London Bridge itself]. [Images: An image of "new houses" built across the river, followed by a spectacular image, by Peter Jackson, of the Old London Bridge itself].– with the former example surely having been at least a subtle influence on the design of Constant's New Babylon –   [Images: Constant's New Babylon – not the same as this New Babylon, of course... though that would be interesting]. [Images: Constant's New Babylon – not the same as this New Babylon, of course... though that would be interesting].– you'd build habitable dams. A whole suburb full of dam-houses, holding back no water. Great arcs of concrete towering over the landscape, full of kitchens. And there's not a river in sight. Or dozens of micro-dams, only three or four stories tall, forming Oscar Niemeyerian monoliths arranged around a cul-de-sac. Families barbecue dinner in the backyard, shaded from the late summer sun by volumetric geometries of well-rebar'd slabs – great dorsal fins of engineering, sticking up from the landscape on all sides.  [Image: The "mechanisms" of Hoover Dam; view slightly larger. Imagine living inside a valve, or inside a penstock...]. [Image: The "mechanisms" of Hoover Dam; view slightly larger. Imagine living inside a valve, or inside a penstock...].You'd come home to this!  [Image: The Eder Dam on the Edersee, Germany]. [Image: The Eder Dam on the Edersee, Germany].Your own little love-nest, nestled between hills – or standing out in the middle of nowhere. The bachelor pad of the future... is a diversionary dam. But habitable dams aren't even the main source of structural ideas that, I think, have been sadly neglected when it comes to designing houses; what really gets me going is thinking about how to use elevated highway ramps as a new form of single-family housing.   [Images: A truly awesome image of an elevated highway-house, architect unknown (if you know, please inform!); and some L.A. freeways, photographed by satellite]. [Images: A truly awesome image of an elevated highway-house, architect unknown (if you know, please inform!); and some L.A. freeways, photographed by satellite].But that will have to wait till another post... The Island of Forgotten Diseases [Images: Vozrozhdeniya Island, via Wikipedia]. [Images: Vozrozhdeniya Island, via Wikipedia].On the desolate central Asian island of Vozrozhdeniye – or Vozrozhdeniya – near the south rim of the shrinking Aral Sea, you'll find "the remains of the world's largest biological-warfare testing ground." As The New York Times reported back in 2002, for nearly four decades Vozrozhdeniye Island was "a practice field for the most hideous kind of warfare." The whole site is now abandoned.  Amidst "hundreds of cages designed to hold guinea pigs, hamsters and rabbits," the New York Times continues, the old Soviet germ labs lie in ruins: Amidst "hundreds of cages designed to hold guinea pigs, hamsters and rabbits," the New York Times continues, the old Soviet germ labs lie in ruins:

In fact, we're told, the "only access to the island now is in the company of the scavengers, who say they began stripping the island bare back in 1996." They've now stolen "everything from floorboards to wiring," and have begun "working on galvanized-steel piping, sealed and towed at a snail's speed to the mainland shore." The real – and much more pressing – question seems to be: what else will these scavengers find on Vozrozhdeniye Island?

Bubonic plague, the article quietly notes, already "affects a handful of people each year in Central Asia." It's here that the ongoing risks of the site are made clear: "if a scavenger contracts the plague and makes it to a hospital, he could start an epidemic." Worse, Vozrozhdeniye Island is now attracting representatives of the oil industry – who have begun to perform some exploratory drilling. What might they really dig up...?  [Image: An aerial view of Kantubek, an abandoned town on Vozrozhdeniye Island; via Wikimedia]. [Image: An aerial view of Kantubek, an abandoned town on Vozrozhdeniye Island; via Wikimedia].The implied storylines here for future science fiction, or horror, films is totally out of control – and yet there is still more to learn about Vozrozhdeniye Island. For instance: it's no longer really an island. The Aral Sea, in which Vozrozhdeniye sits, has been evaporating since the 1980s, due to catastrophically mismanaged Soviet irrigation plans – which means that Vozrozhdeniye is now a peninsula. This otherwise unremarkable geographical shift has frightening implications:

According to "a previously secret Soviet medical report," which included "autopsy reports, pathology reports, containment tactics, and an official Soviet analysis of the outbreak's source," there were 10 cases of smallpox reported in Aralsk alone – after which "officials quarantined the city for weeks." In the process, "Homes and belongings were decontaminated or burned." Potential novelists or screenwriters might want to start paying attention here, though, because this is a near-perfect plot device.

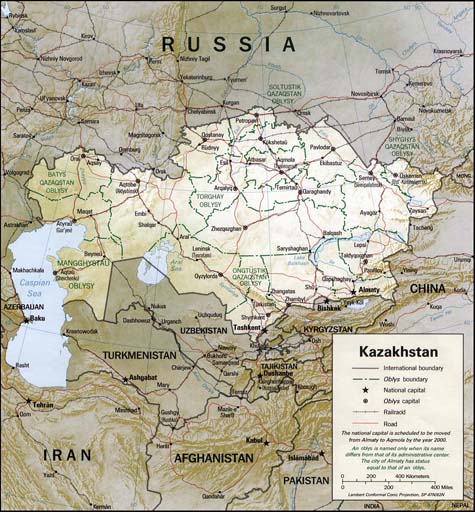

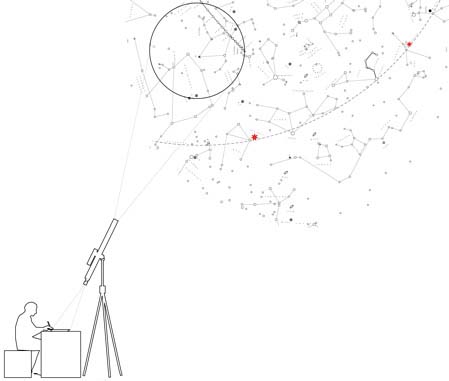

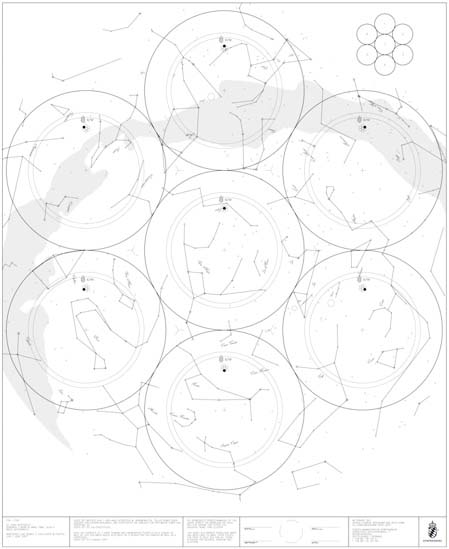

You can read more about the outbreak at the website of Sandia Labs. Finally, there was even speculation, back in 2001, that Vozrozhdeniye Island may have been distantly involved in the U.S. anthrax attacks. But I could go on and on. If you want to know more, though, just follow the links, above, or check out CNN – and, if you're a budding novelist, and you decide to go somewhere with this material, let me know! And if you're anywhere near the Aral Sea, beware the wind... (Thanks to Neddal Ayad for pointing Vozrozhdeniye Island out to me!) Gastro-Astronomical Tableware [Image: Locating your own constellations for My Private Sky; via dezeen]. [Image: Locating your own constellations for My Private Sky; via dezeen].dezeen's got the goods on a new line of plateware that brings astronomy to your dinner table:

[Image: Painting the plates of My Private Sky; via dezeen]. [Image: Painting the plates of My Private Sky; via dezeen].If I can be permitted a fairly self-indulgent side-note, meanwhile, this is actually similar to something my wife and I did for our wedding invitation. Since we got married in London – and since we're so romantic we make fire retardants burn – we had the Royal Observatory at Greenwich generate a star-map (free of charge!) showing what the skies would look like at 10pm on the evening of our wedding (see an incredibly blurry photograph of said invitation here), with the effect that, once the party was over and you were falling down drunk, you could crawl outside onto the gravel path and look up... awed by the sight of a whole sky's worth of stars exactly as it appeared on the wedding invitation. I don't think anyone actually did this – minus the falling down part – but hey.  [Image: Sample plate designs for My Private Sky; via dezeen]. [Image: Sample plate designs for My Private Sky; via dezeen].We later learned that there is a similar sort of star-map embedded in the concrete at Hoover Dam. In any case, read more about My Private Sky at dezeen. Snake Of Earth [Image: The Earth, as it appears from above, outside Mexican Hat, Utah: sliced by the great lobed canyons of a desert riverbed. I believe you're looking down at Goosenecks State Park. Images collected via Google Maps. View bigger. Earlier: Fossil Rivers]. [Image: The Earth, as it appears from above, outside Mexican Hat, Utah: sliced by the great lobed canyons of a desert riverbed. I believe you're looking down at Goosenecks State Park. Images collected via Google Maps. View bigger. Earlier: Fossil Rivers].

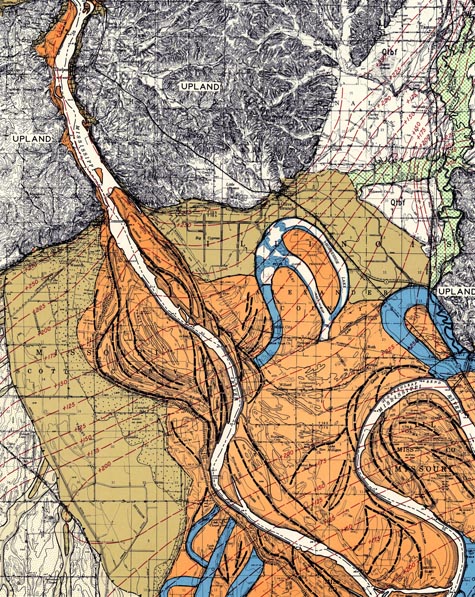

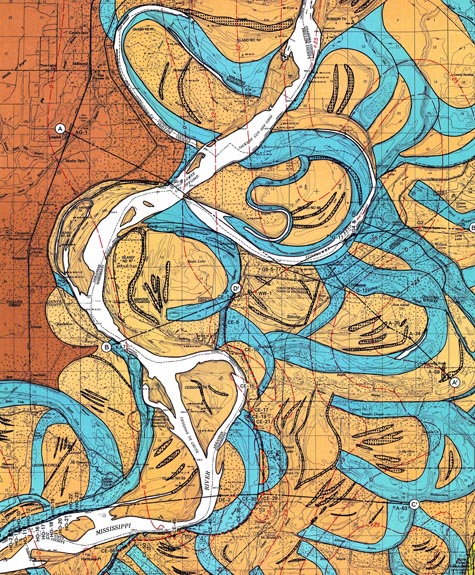

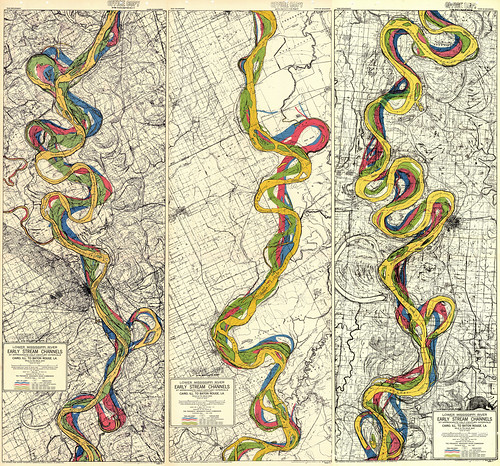

Fossil Rivers [Image: A page from Blend, a Dutch magazine for whom this post was originally written, back in September 2006; if the tone of this post feels like an article, that's why]. [Image: A page from Blend, a Dutch magazine for whom this post was originally written, back in September 2006; if the tone of this post feels like an article, that's why].The geological history of the Mississippi River has been extensively documented by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers for more than a century. The Corps has produced maps, charts, graphs, and illustrated reports. Taken together, these offer a snapshot of the Mississippi, from source to sea, including the river's "subsurface conditions," its ancient geological forms, and its present-day urban surroundings. We see the grids of existing cities – New Orleans, Baton Rouge, St. Louis – built upon the shores of the world's fourth-largest river; and we see remnant landscapes of eroded bedrock from a time before humans ever set foot upon North America. This is the "ancestral" Mississippi, a lost waterscape of "meander belts" and "alluvial aprons," now visible only to the eyes of trained geologists.  [Image: The Mississippi River in its geological context, as mapped by the Army Corps of Engineers. Worth viewing bigger]. [Image: The Mississippi River in its geological context, as mapped by the Army Corps of Engineers. Worth viewing bigger].Luckily, if geology bores you, the Corps’s maps are visually spectacular – beautiful to the point of near disbelief. Colors coil round other colors; abstract shapes knot, circle, and extend like Christmas gift ribbons. This is geology as a subset of Abstract Expressionism: rocky loops of the Earth’s surface in the hands of Jackson Pollock.  [Image: The Mississippi and its ancient side-routes; mapped by the Army Corps of Engineers. For a browser-crashing, eye-popping, dorm room-decorating, huge version, click here! Beware heart attack! Don't do while driving!]. [Image: The Mississippi and its ancient side-routes; mapped by the Army Corps of Engineers. For a browser-crashing, eye-popping, dorm room-decorating, huge version, click here! Beware heart attack! Don't do while driving!].In the maps, different colors represent routes of the Mississippi as recorded by the Corps at "approximate half-century intervals" – indeed, the river can shift that much, tracing whole new geometries in less than a century. In some maps not included here, for instance, this rate of change grows more extreme. We glimpse the Mississippi in its true historic dimensions, where it becomes a labyrinth of conflicting riverbeds, each one disappearing slowly, inevitably, over thousands of years, only to be replaced, abruptly, by new directions and forms – that will themselves disappear later. These maps document time, in other words, as much as they document geography.  [Image: The Mississippi, beautifully – even sublimely – mapped by the Army Corps of Engineers; view larger!]. [Image: The Mississippi, beautifully – even sublimely – mapped by the Army Corps of Engineers; view larger!].The sheer fact that cities have been built in the midst of this mobile terrain is either horrifying or vaguely hilarious. The "land" all these cities are constructed on is actually hundreds of thousands of acres of displaced mud, thick sheets of soil washed down from the north and compacted over time into something approximating solid ground. But there is no solid ground here: it is an unstructured mush of erased landscapes, a syrupy blur. The river meanders, creating surface here, surface there – solidity nowhere. The waters curve eastward, then westward, then back again, redesigning the central landscape of the United States, draining North America.  [Image: The Mississippi as mapped by the Army Corps of Engineers; see bigger!]. [Image: The Mississippi as mapped by the Army Corps of Engineers; see bigger!].Indeed, what the Army Corps of Engineers discovered while producing these maps is that the Mississippi River has changed channel completely – and it has done this hundreds, even thousands, of times. In fact, the river's endless self-alteration still occurs, even as you read these words: the Mississippi, like all rivers, is migratory, destined to wander across the landscape for as long as it continues to flow. It drifts back and forth – sometimes a few feet, sometimes a mile – walled in by its own silt and debris; until there is change: a natural levee fails, or a storm surge bursts into another watercourse nearby, and then the river finds itself on a quick new route to the sea. These old routes, of course, leave traces: eroded deep into the rock and soil, or piled high in distant mounds, running across the backyards of farmers, forming ponds, they are the fossils of ancient landscapes – lost rivers locked in the ground around us.  [Image: Lost sub-rivers of the Mississippi, in a region called Onward, mapped by the Army Corps of Engineers; view this bigger!]. [Image: Lost sub-rivers of the Mississippi, in a region called Onward, mapped by the Army Corps of Engineers; view this bigger!].If you are the Army Corps of Engineers, however – a branch of the U.S. military – then your mandate is to secure the nation’s waterways. The Mississippi’s relentless change in shape and direction is thus not a topic for poetry but a matter of national security. Through their infinite encyclopedia of the river – constantly updated, never complete – the Corps hopes to control these riverine transformations. Their goal is made almost comically obvious when you note that these maps are printed by the “War Department.” This is a battle strategy: it is geomorphic warfare. Simultaneous with the realization that the Mississippi is a landscape on the move, the Army Corps of Engineers launched a much larger project, and that was to fix the path of the Mississippi in place – forever. It sought to do this through architecture, installing monumental locks and dams up and down the river’s route, controlling rates of flow, sediment, ship traffic, flash floods, and so on. For thousands of miles, then, the Mississippi would be a landscape held literally under martial law.  [Image: The Mississippi as mapped by the Army Corps of Engineers; check out the big version]. [Image: The Mississippi as mapped by the Army Corps of Engineers; check out the big version].This is sheer folly for anyone who looks at the Corps's own maps. Meadows and hillsides once located hundreds of miles away have been reduced to nothing but mud braided on the bottom of the Mississippi River, clumped high in deltas, spread wide over lobes upon which whole towns have now been built.  [Image: Early stream channels of the Mississippi, geologically charted by the Army Corps of Engineers; view it larger and freak out]. [Image: Early stream channels of the Mississippi, geologically charted by the Army Corps of Engineers; view it larger and freak out].But someday even the Corps’s pharaonic locks and dams will be mere sand on the shores of a future Mississippi. All these misguided control structures – and the cities they protect – will disappear, glittering in the currents like Rhinegold... before they, too, are lost to the river forever. (Note: I'm hugely endebted to Alex Trevi, of Pruned, without whom I would not have seen these maps when I did... and this article would thus never have been written. In fact, if you squint, and lean in close to the monitor, you'll notice that I thank him in the original article, reproduced above. In any case, if you like what you see here, don't miss Alex's own investigation of this subject matter!). The Weather Emperors [Image: From Blend, a Dutch magazine for whom I wrote a monthly column from January 2006 to June 2007]. [Image: From Blend, a Dutch magazine for whom I wrote a monthly column from January 2006 to June 2007].One of the most interesting—if unexpected—side-effects of global climate change is that the Alps are growing taller. According to New Scientist, warmer temperatures have been causing those mountains to "shed the weight of their glaciers," with the result that "the unburdened crust beneath them is rebounding, causing the mountain range to rise slowly." Mont Blanc, for instance, "where the melting is fastest, is growing by as much as 0.9 millimetres per year due to climate change." Less than one millimeter per year isn't much, but these deep and shuddering geological adjustments are exhibiting effects elsewhere—such as increasing the rate of seismic activity throughout the Alpine region (with the mountains themselves literally shattering as old faults decompress). Amazingly, this Alpine growth spurt has actually begun to alter wind patterns flowing across the greater European landmass. In other words, the weather will begin to change yet faster—feeding back and changing the very tectonic structure of the continent.  [Image: Mont Blanc]. [Image: Mont Blanc].Meanwhile, in other climate news, cities—and this is obvious to anyone who has ever set foot in one—are hotter than the surrounding countryside. This difference can be as much as 10ºC, New Scientist reports. The built environment simply absorbs more heat than the surrounding landscape, with roads, freeways, car parks, roofs of buildings, etc., all baking slowly in the afternoon sunlight. This is the appropriately named urban heat island effect. From New Scientist:

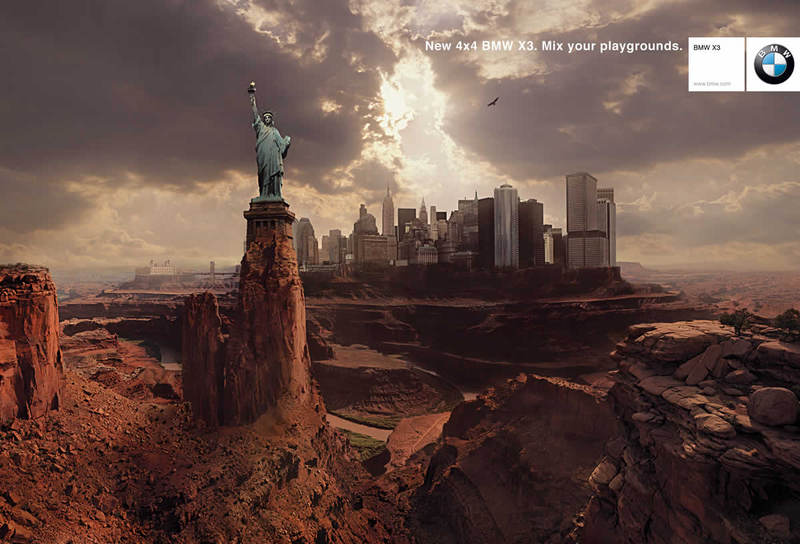

This means that strange weather, including extra rainfall and more violent thunderstorms, can be expected "up to 60 kilometres downwind of cities such as Dallas and Atlanta"—not to mention cities like London, Paris, Venice, Sydney, Tokyo, and so on. So if it's raining in your home town tonight: blame the nearest city. Which leads me to wonder: is there a particular patch of sea somewhere outside New York City where the winds are stronger, or the waves more violent, or the rain more extreme—and it's all of because of the complex downwind effects of Manhattan...? Does New York have a climatic presence in the north central Atlantic? The city as a kind of storm valve, regulating weather for distant ships...  [Image: The topography of the Alps]. [Image: The topography of the Alps].In any case, putting these two bits of news together, perhaps we could build something—a structure or some sort of device—that would take advantage of both Alpine growth and excessive urban heat. If we combined these two stories, for instance, a new kind of military tactic takes shape: you build strange, fortified, geologically monumental weather-affecting landscapes all over the world – and then destroy distant targets downwind. The Thames Estuary could be lined with a series of heated platforms—large towers, like ovens—pointed toward Europe. This artificially generated microclimate would then be weaponized and run by the British military, who would lay claim to the weather itself. Amsterdam could be washed away in a fortnight, Paris held hostage for years. Or perhaps an armada of heated ships could be sent to the South China Sea... and Beijing becomes servant to the Queen. China’s soldiers will be blown over as umbrellas are inverted throughout the country, and the nation’s stock of nuclear missiles is redirected north, by wind, into the thawing wastes of Siberia. It would be the world's first air weapon, shooting bad weather on demand.  [Image: A hail cannon, via a website about weather modification. For a bit more on hail cannons, see BLDGBLOG's Quick list 7 (scroll down)]. [Image: A hail cannon, via a website about weather modification. For a bit more on hail cannons, see BLDGBLOG's Quick list 7 (scroll down)].On another note, I read several years ago about an Australian home-owner who once found strange and unexpected flowers blooming in the family garden. These were flowers that he'd never seen before—and that he'd certainly never planted—so what soon became clear was that a drought on the other side of Australia, coupled with unseasonably strong winds, had blown seeds and a thin mist of soil throughout the country... some of which had come to settle in this man’s garden. He was a victim of the weather, botanically vandalized. Perhaps, then, instead of unleashing storms upon distant opponents, you could convert the air weapon to a more useful, peacetime purpose: horticulture. Gardens at a distance. You'd throw exotic seeds into gathering breezes—and, within weeks, distant hillsides would color and bloom with breadfruit and roses, berries and genetically modified knotweed. Shift the direction of the wind and a hundred miles of orange trees take root, forming orchards; shift the wind yet again, and uncountable acres of lavender, mint, rosemary, white pine, and birch appear, as you reforest the world from afar. So, as the Alps grow taller and as continental wind systems shift, perhaps we’ll find that the balance of power in Europe shifts upward.  [Image: Chimneys, via Wikipedia]. [Image: Chimneys, via Wikipedia].There, on the slopes of snowless mountains will sit strange ovens in towers, blowing both weather and seeds over the horizon of nations below. Amidst angled platforms and wind-ramps, a new breed of rulers grows strong, distributing gardens and thunderstorms upon those countries they now dominate. The Weather Emperors, ruling Europe from above. Until a small group of irritated gardeners, congested with allergies and choking on seeds, begins to climb up the Alpine front, intent on liberating their countrymen from this artificial weather. They haul themselves through rocky passes and eat rare Peruvian fruit that now grows freely in Swiss crevasses. They pull each other up toward the storm machines, those great chimneys spewing unwanted landscapes upon the flatlands of central Europe. The rebels approach the nearest tower, hammers raised. (Other articles written for Blend include Urban Knot Theory, Abstract Geology, Wreck-diving London, and The Helicopter Archipelago – and there will soon be many more, reproduced here on BLDGBLOG. Meanwhile, I can't find the original articles that I'm quoting in this essay; till I find the appropriate citations—sorry!—here's a bit more on the post-glacial growth of the Alps). New York Canyonlands [Image: Another ad for BMW – see the one featuring London – this time transforming New York City into a desert city on the Arizona-Utah border, perched on geological outcrops and overlooking slot canyons. Rumor has it, Lebbeus Woods has an image much like this...? Ad discovered via Design Bivouac, thanks to a tip from Kosmograd. View a slightly larger version]. [Image: Another ad for BMW – see the one featuring London – this time transforming New York City into a desert city on the Arizona-Utah border, perched on geological outcrops and overlooking slot canyons. Rumor has it, Lebbeus Woods has an image much like this...? Ad discovered via Design Bivouac, thanks to a tip from Kosmograd. View a slightly larger version].

New York City in Sound [Image: Manhattan, as photographed by Dan Hill]. [Image: Manhattan, as photographed by Dan Hill].Back in April, BLDGBLOG interviewed Walter Murch. Murch has been a film editor and sound designer for nearly four decades; he has won three Oscars and two BAFTA Awards in the process (among many other accolades); and he is the subject of an excellent, often riveting, book-length collection of interviews, called The Conversations: Walter Murch and the Art of Editing Film, conducted and assembled by novelist Michael Ondaatje. You can read the BLDGBLOG interview with Murch here – where you'll notice that I ask Walter, toward the end of our discussion, about sounds and the city: what makes cities sound the way they do? Can these acoustic properties be artistically re-shaped, or somehow musically used? In response, Murch cites a short essay written by filmmaker Michelangelo Antonioni in which Antonioni describes what it feels like to listen to Manhattan – as one would listen to a distant symphony, or to the sounds of a unfamiliar instrument. That essay, with a new introduction by Walter Murch, is now reprinted here, in full, on BLDGBLOG. by Walter Murch Manhattan: remorseless grid of right-angle streets rescued by a jumble-sale of architectural styles thrown together by history and human will-power. Paris (or Prague, or perhaps any other European city): ancient broken crockery of random-angled streets repaired by architecture of great stylistic and cultural coherence. Confronted with the classically American paradox of Manhattan’s simultaneous rigidity and exuberance, the refined European sensibility discovers that...

It was only years later when I was living in the Prati district – Rome's version of Manhattan's Upper West Side – that I saw cornices as they were intended: a continuous horizontal line atop several buildings, gathering them together in a single conceptual frame. When I returned to my old neighborhood in Manhattan, it now looked wondrously stalagmitic. Sometime after the success of his film Blow-Up (1966), the Italian director Michelangelo Antonioni visited Manhattan, thinking of setting his next project in New York. Confused and overwhelmed by the city's visual foreignness, he decided to listen rather than to look: to eavesdrop on the city's mutterings as it emerged into consciousness from the previous night's sleep. Sitting in his room on the 34th floor of the Sherry-Netherland Hotel, Antonioni kept a journal of everything he heard from six to nine in the morning... Perhaps some inadvertent sound might provide the key to unlock the mysteries of this foreign world.  [Image: Looking down at the roof of Manhattan's Sherry-Netherland Hotel, via New York Architecture Images]. [Image: Looking down at the roof of Manhattan's Sherry-Netherland Hotel, via New York Architecture Images].His New York film was never made, but the pages of Antonioni's bedside vigil survive, and were published at a conference on film sound that I attended in Copenhagen in 1980. The organizers of that conference – composer Hans-Erik Philip and filmmaker Vibeke Gad – have generously allowed BLDGBLOG to reprint Antonioni's poetic soundscape of a long-vanished Manhattan, filtered through the Italian sensibility of his acutely sensitive cinematic ear. The soundtrack for a film set in New York – circa 1970 by Michelangelo Antonioni There is a constant murmur, hollow and deep: the traffic. And another sound, intermittent: the wind. It comes in gusts, and in the pauses I can hear it sighing, far away, against other skyscrapers. Here, on the thirty-fourth floor, I can feel the vibration of every gust. It gives me a strange feeling as if, for a few moments, my brain freezes. A faint, short-lived siren comes and goes. The noise of two car-horns. A rumble that approaches but is impatiently eclipsed by a sudden buffet of the wind. A tram car. It is six o'clock in the morning. Another rumble blends with the first, then drowns it. A faint explosion, far, far away. The wind returns, rising from nothing, spreading, it seems to stretch in the still air, then dies. The hint of a tram, faint, remote. It is not a tram, after all, but another kind of sound I cannot recognize. A truck. A second one, accelerating. Two or three passing cars. The roads in Central Park twist and turn. A line of cars. Their exhausts a kind of organ playing a masterpiece. A moment of absolute silence, eerie. A huge truck passes. It seems so close that I feel I am on the second floor. But that sound, too, quickly fades. A squeal. A ship's siren, prolonged and melancholy. The wind has dropped. The siren again. The murmur of traffic beneath it. A bell, off key. From a country church. But perhaps it is the clang of iron and not a bell. It comes again. And still once more. A car engine races, furiously, with a sudden spurt of the accelerator. In a momentary hush, the siren again, far away. The metallic echo rises. A terribly noisy truck seems just outside the window. But it is an aircraft. All the sounds increase: car-horns, the siren, trucks; and then they recede, gradually. But no, another rumble, another siren. Irritating, persistent, right across the horizon. Quarter past six: the same series of sound in waves, each in turn, clearly defined. Brief intervals. A murmur continues. And, always, the siren. An abrupt car-horn, very far away. Another muffled beneath it. Somewhere on a distant street, a car, very fast, perhaps European. The wind swirls against the wall outside. A single gust., immediately swallowed by a raucous truck and then a newer vehicle, steadier. The throb of the two different motors driving off, merging into one. But it is not a truck, it’s an aircraft. No. Not an aircraft. A noise that rises and becomes deafening, only to fade unidentified. All that remains, obsessive, is the siren. And someone whistling (how can that be possible?) instantly drowned by an angry car-horn. Sounds of metal sheets thrown together. Clear and sharp, a winch. The sound of cogs. But it cannot be a winch, and this constant whine is not the siren. More sheets, more metallic. Then a hollow boom, barely audible, but lingering in the air. A faint hum suddenly stops. A car passes, another, then a third, fading, fading, fading. They mingle with other cars, other sounds. An aircraft seems to take off from right beside the building. And as suddenly as it appeared, it is gone. The very beautiful roar of a car, completely appropriate for this moment. It speeds past and dies, distinct, satisfying. Two tones shimmer. A gust of wind.  [Image: A view of Central Park, via Wikipedia]. [Image: A view of Central Park, via Wikipedia].Half past six: more gusts. A furious flurry of wind between the skyscrapers slides away and buffets across the park. Only a car-horn interrupts, like a slap in the face. The wind drops. A peal of bells in the stillness. And always, the siren. A tone higher now. It wasn’t bells. It is my Italian ear that hears it that way. The sheets of metal. A short clatter, like gunfire. A train passes, perhaps the elevated. A peal, prolonged, and then the siren, abrupt. Gone. The sounds change in a moment, they arise and die again immediately. The hum reasserts itself, advancing like a camouflaged army, approaches, closes in, on the alert, ready to take over completely. It is very close. One can distinguish the wind, the cars, the aircraft, a clash of iron, and the siren. They advance, determined, against this skyscraper hotel. In the forefront, the sound of iron, but the aircraft closes in and takes over alone. And now – nothing. The struggle is over. A small revolution quelled by the authority of a car-horn. The banging of wood. A pause. More banging. They must be moving tables. It sounds like a machine gun that is falling apart. The cars are under fire. They have to pull up and stop. Another siren, more real. The rumble of wheels, but it is not a car. It is the wind, which has risen again. Strong, but not strong enough to cover the aircraft. Cars. A roar, as if from a cannon, echoless. Here and there, metallic sounds of various intensities. A roar of wind. The roar of a truck. The roar of the elevated railway. Two thuds in different tones. The noise grows and then stops suddenly, as if cut off by the thuds as they start again. Other sounds are born, clear yet unrecognizable. A long, startling car-horn. A sound that does not die, that will never die. I cannot hear it any longer, but it has left me with this certainty. But the sound of the siren is dying. A gust of wind pushes it away, but a truck rises. Then diminishes in turn and mingles with the wind. Some kind of bell. A voice is heard. The first voice. Seven o'clock: A blast from the siren, as if to remind me of its existence. Now imperceptible, yet insistent. The squeal of tires. A thundering, a rumble, somewhere underground. Half-past eight: And now the sun has risen, but the sounds are still the same. With one exception. Drills. Nasty. Destroying a building. They are far away but occasionally, because of the wind, they are perfectly distinct. The other sounds remain. A whistle, shrill, anxious. It repeats – urgently. A noisy engine, I don't know what kind. And loud, yet distant, the drills. The only change is that it has all become stronger with the daylight. The wind, the cars, the siren. Only the car-horns are less strident, more discrete, a reflection on the drivers who obey New York’s traffic laws: they must use their horns only when absolutely necessary. They cannot afford the fines, and so they obey the law, which seems a little Teutonic. I imagine the drivers in this bewildering noise, melted together, inside their creeping cars: noise that hasn’t the courage to explode, but hovers in the air, in the spring-like, clear, clean winter air. (BLDGBLOG owes a huge and genuine thank you to Walter Murch, Hans-Erik Philip, Vibeke Gad, and, of course, Michelangelo Antonioni for the permission to reprint this essay. Meanwhile, if this post appealed to you, I'd urge you to take a look at BLDGBLOG's interview with Walter Murch, where some of these points are developed further – or simply to pick up a copy of The Conversations: Walter Murch and the Art of Editing Film, edited by Michael Ondaatje. Of course, Murch is both the subject and author of many other books and articles – links to which can be found embedded in the BLDGBLOG interview. Finally, keep an eye out for Antonioni's own The Architecture of Vision: Writings and Interviews on Cinema, due out in November 2007).

|